World War I (1914-1918) was a conflict that involved more countries and caused greater destruction than any other war up to its time. Following an assassination in Bosnia-Herzegovina, a system of military alliances (agreements) plunged the main European powers into a war that lasted four years. The war took the lives of about 9 million troops and more than 6 million civilians. World War I is sometimes called the Great War.

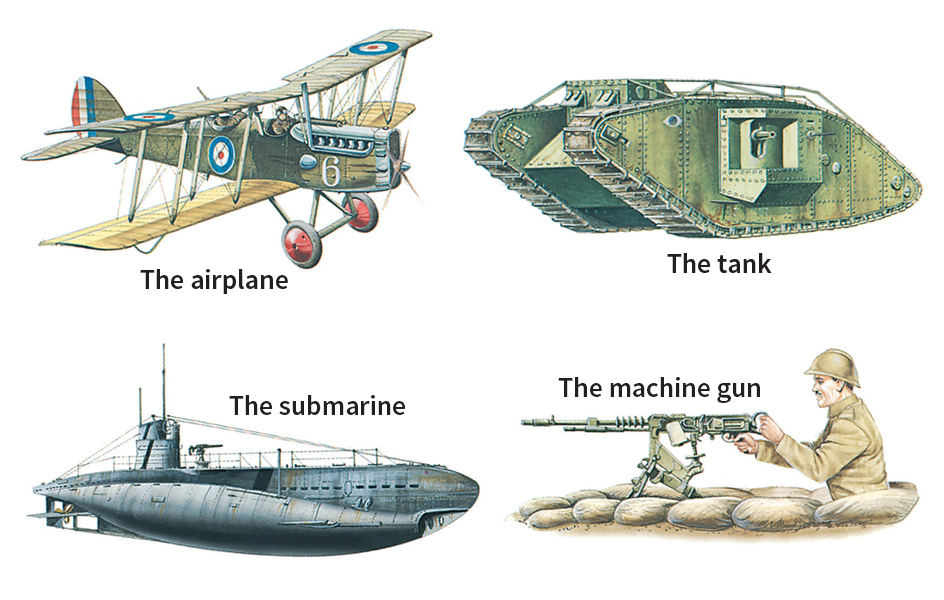

A number of developments contributed to the awful bloodshed of World War I. Military drafts raised larger armies than ever before. Industries equipped those armies with new and dangerous weapons. Barbed wire slowed the movement of troops across the battlefield, and machine guns fired hundreds of shots in less than a minute. Armies fought from vast systems of trenches (fortified ditches). Government propaganda (communication intended to shape people’s beliefs) whipped up support by making enemy nations seem villainous.

The conditions that led to World War I took shape over several decades. The unification of Germany in 1871 had created a powerful and fast-growing new state in the heart of Europe. In the early 1900’s, Germany’s quest for power caused a series of crises. Armed forces expanded, and Europe’s great powers formed alliances and prepared for war.

An assassination on June 28, 1914, sparked the outbreak of World War I. That day, a gunman shot down Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria-Hungary . The shooting took place in Sarajevo, the capital of Austria-Hungary’s province of Bosnia-Herzegovina . Austria-Hungary and Serbia had long-running tensions, and Austria-Hungary believed Serbia’s government was behind the assassination. Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia.

When the fighting began, each nation’s allies became involved in the conflict. France , Russia , and the United Kingdom —collectively known as the Entente—backed Serbia. They opposed the Central Powers, made up of Austria-Hungary and Germany. Other countries later joined each alliance. The Entente and its allies came to be known as the Allies.

Germany won early victories on the main European battlefronts. On the Western Front, France and the United Kingdom halted the German advance in September 1914. The opposing armies then fought from trenches that stretched across Belgium and northeastern France. The Western Front hardly moved for the next 3 1/2 years. On the Eastern Front, Russia battled Germany and Austria-Hungary. The fighting there seesawed back and forth until 1917. That year, revolution broke out in Russia, and a new Russian government asked for a truce.

The United States remained neutral at first. However, many Americans turned against the Central Powers after German submarines began sinking unarmed ships. In 1917, the United States joined the Allies. The support of the United States gave the Allies the resources and resolve they needed to win the war. In the fall of 1918, the Central Powers surrendered.

World War I had results that none of the warring nations had foreseen. The war helped topple monarchs in Austria-Hungary, Germany, and Russia. The peace treaties after the war carved new countries out of the defeated powers. Europe never regained the leading position in world affairs that it had before the war. The continent’s weakened condition led to the rise of extreme political groups in some nations. Conditions in Europe at the end of the war set the stage for further devastation in World War II (1939-1945).

Background to the war

Europe had effectively avoided major wars in the 100 years before World War I. Stability was maintained largely through a balance of power among Europe’s leading nations. This balance rested on the somewhat even distribution of military and economic might.

By the early 1900’s, however, various events had begun to upset the balance of power. Russia, defeated in a war with Japan and recovering from a brief revolution, began strengthening its military. A series of internal wars threatened the stability of the Ottoman Empire , which was centered in what is now Turkey.

Unrest in the Balkans —the states on the Balkan Peninsula in southeastern Europe—led to struggles for control. Serbia led a movement to unite the region’s ethnic Slavs . Russia, the most powerful Slavic country, generally supported Serbia. Austria-Hungary, however, feared Slavic nationalism —that is, the sense of belonging to a nation. Millions of Slavs lived under Austria-Hungary’s rule.

In 1908, Austria-Hungary angered Russia and Serbia by annexing the Balkan territory of Bosnia-Herzegovina. Serbia wanted control of the area because many Serbs lived there. The Balkan Wars of 1912 and 1913 created still more tension in the region.

A build-up of military might

took place in Europe in the years leading up to World War I. The continental powers relied on conscription (forced military service) to create large armies . The general staffs of European nations created detailed plans for war.

Before World War I, the United Kingdom did not use conscription to build a large army. An island country, it instead relied on its Royal Navy for defense. In 1898, Germany began building a naval force big enough to challenge the British Navy. In 1906, the British Navy launched the first modern battleship , Dreadnought . Dreadnought had greater armor and firepower than any other ship of its time. Germany rushed to construct warships like it.

Advances in technology increased the destructive power of military forces. Machine guns and artillery (large, mounted guns that hurl explosive shells) fired more accurately and more rapidly than earlier weapons. Steamships and railroads could speed the movement of troops and supplies. Barbed wire could stop or slow enemy troops.

European political and military leaders did not immediately recognize the impact of these new technologies on warfare. Most of them expected the new war of 1914—World War I—to be bloody, but short.

The development of empires

created tensions in Europe during the late 1800’s and early 1900’s. European nations carved nearly all of Africa and much of Asia into colonies. The colonies supplied the great powers with vast amounts of raw materials and, once war began, with soldiers as well.

A system of military alliances

gave European powers a sense of security before World War I. Nations entered into military agreements to protect against attacks from rival nations. If one member of an alliance were to be attacked, other members of the alliance would agree to come to the country’s aid or at least remain neutral.

Although military alliances provided protection, they also created dangers. For instance, the security of an alliance might lead a nation to take risks in dealings with other nations that it would hesitate to take alone. In addition, the alliance system increased the risk that a dispute between two nations could escalate into a conflict involving many nations. Alliances could force a country to go to war against a nation with which it had no quarrel.

Finally, the terms of many alliances were secret. This secrecy increased the chances that a country might misjudge the consequences of its actions.

The Triple Alliance.

Following the unification of Germany in 1871, German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck formed a series of alliances to strengthen his country’s security. He first made an ally of Austria-Hungary. In 1879, Germany and Austria-Hungary agreed to go to war together if either country were attacked by Russia. Italy joined the agreement in 1882. The group then became known as the Triple Alliance . The members of the Triple Alliance agreed to aid one another in the case of an attack by two or more countries.

Germany’s relations with other European countries worsened after Bismarck left office in 1890. Bismarck had worked to prevent France, Germany’s neighbor on the west, from forming alliances with Russia and Austria-Hungary, Germany’s neighbors to the east. In 1894, however, France and Russia agreed to mobilize (call up troops) if any nation in the Triple Alliance did the same. France and Russia also agreed to help each other if either were attacked by Germany. This agreement led Germany to plan for war on two fronts at the same time.

The Triple Entente.

In 1904, the United Kingdom and France settled their past disagreements over colonies and signed the Entente Cordiale (Friendly Agreement). Though the agreement contained no pledges of military support, the two countries began to discuss joint military plans. In 1907, the United Kingdom and Russia settled their differences in Asia. Russia then joined the alliance. This new Triple Entente existed mainly to combat the threat of Germany’s growing power.

The development of military alliances left Europe divided into two opposing camps. Still, war was not inevitable. Germany’s relations with France and the United Kingdom were improving by 1914. And nothing in either alliance demanded a state go to war if an ally was the aggressor. The alliances were intended to deter (discourage) war, not ignite it.

The beginning of the war

World War I began in the Balkans, an area with a long history of conflict. In the early 1900’s, the Balkan states fought the Ottoman Empire in the First Balkan War (1912-1913). The states battled one another in the Second Balkan War (1913). The major European powers stayed out of both wars. However, they did not escape the third Balkan crisis.

The assassination of an archduke.

Archduke Franz Ferdinand was the heir to the throne of Austria-Hungary. Hoping to ease tensions between Austria-Hungary and the Balkan nations, he arranged to tour Bosnia-Herzegovina with his wife, Sophie. As the couple rode through Sarajevo on June 28, 1914, an assassin fired two shots into their automobile. Franz Ferdinand and Sophie died almost instantly. The murderer, a young Bosnian Serb named Gavrilo Princip, had links to a Serbian terrorist group called the Black Hand.

The assassination of Franz Ferdinand gave Austria-Hungary a reason to attack Serbia, its long-time enemy in the Balkans. Austria-Hungary first obtained Germany’s promise of support for action against Serbia. It then sent a list of demands to Serbia on July 23. Serbia accepted most of the demands and offered to settle the rest through an international conference. Austria-Hungary, however, rejected the offer. Expecting a quick victory, Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia on July 28.

The conflict spreads.

Germany’s support of Austria-Hungary put it at odds with Russia, which supported Serbia. The Germans hoped Russia would not step up to help Serbia. Previously, after Austria-Hungary had angered Serbia by taking over Bosnia-Herzegovina in 1908, Russia had stepped aside. This time, however, Russia took action.

Russia’s czar (emperor) decided to mass troops along Russia’s border with Austria-Hungary. Russia’s military leaders persuaded the czar to mobilize along the German border, too. On July 30, Russia announced it would mobilize its entire, massive army. Reacting to Russia’s actions, Germany also began general mobilization.

Germany, well aware that the conflict would spread, declared war on Russia on Aug. 1, 1914. France then called up its troops in support of Russia. On August 3, using false claims of French attacks, Germany declared war on France.

Germany decided to attack France from the north, through neutral Belgium. Its army swept across the Belgian border on August 4. This invasion caused the United Kingdom to declare war on Germany. Within a week, the Balkan crisis had dragged Europe’s great powers into World War I.

The Western Front.

Alfred von Schlieffen, former chief of the German General Staff, had developed the main ideas of Germany’s war plan in 1905. The Schlieffen plan assumed that Germany would have to fight both France and Russia. According to the plan, the Germans would aim to defeat France quickly while Russia slowly mobilized. The Germans would then deal with Russia after the defeat of the French. After 1910, however, Russian mobilization times improved, thanks in part to French investment in Russian railroads.

France had a network of forts along the German border. To bypass these defenses, the Schlieffen plan called for a strong right wing to swing through Belgium and then hit France from the north. A left wing of German forces would move toward eastern France. Schlieffen’s hope was that the right wing could get behind the bulk of the French army. The wing would then pin the French against their eastern fortresses and the Swiss frontier.

Schlieffen’s successor, Helmuth von Moltke, directed German strategy at the outbreak of World War I. Moltke recognized that the French army was modern and well-led. He also knew the Schlieffen plan was an enormous gamble. If it failed, Germany would be forced into a two-front war against numerically superior forces. Germany’s only chance was to win quickly, with devastating force.

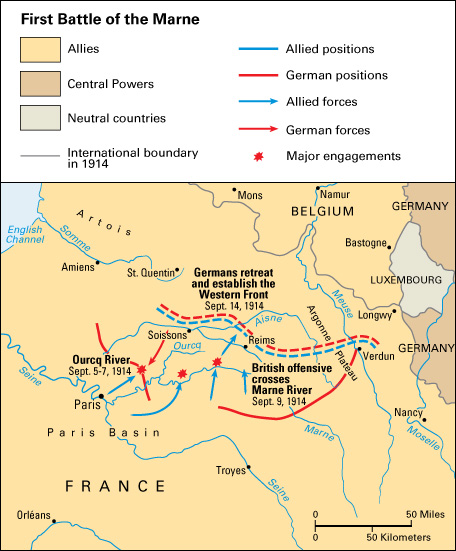

On Aug. 16, 1914, Germany took the eastern Belgian city of Liège . Belgian troops fought bravely, but heavy German guns forced the city’s forts to surrender. German troops then pushed across Belgium, killing many Belgian civilians suspected of resisting. The German army drove back French forces and a small British force in southern Belgium. The Germans then swept into France. One part of the right wing pursued retreating French troops southeast across the Marne River. The pursuit left the exhausted Germans exposed to attacks from Paris, just 30 miles (48 kilometers) away.

General Joseph Joffre , commander in chief of all the French armies, prepared a counterattack. He stationed his forces near the Marne River east of Paris. Fierce fighting began on September 6. The conflict became known as the First Battle of the Marne . On September 9, German forces started to withdraw. The French and Germans each suffered around 250,000 casualties (people killed, wounded, or captured). About 12,000 British troops were killed or wounded.

The First Battle of the Marne was a key victory for the Allies. It ended Germany’s hopes to defeat France quickly. Erich von Falkenhayn replaced an ailing Moltke as chief of the German General Staff.

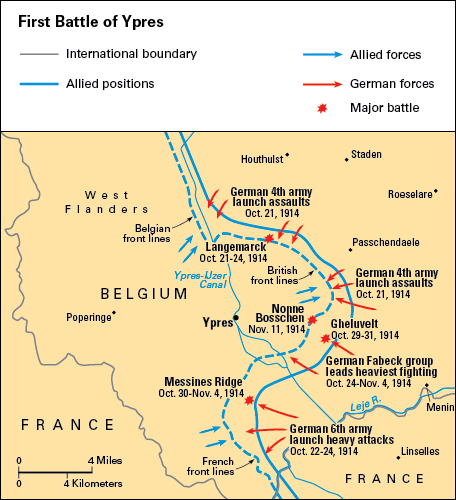

The German army halted its retreat near the Aisne River, in northeastern France. From there, the Germans and the Allies fought a series of battles. In the last of the battles, the First Battle of Ypres in Belgium, the two sides fought to a standstill. From mid-October until mid-November, there were over 200,000 casualties.

In the fall of 1914, the Germans established deep defensive positions along the high ground they had captured in Belgium and northeastern France. Falkenhayn’s aim was to free up German troops for use elsewhere. But his plan instead created a deadlock on the Western Front. The opposing sides dug networks of trenches as protection against machine guns and artillery. Nearly four years of brutal trench warfare followed.

The Western Front extended more than 450 miles (720 kilometers). It stretched from the coast of Belgium in the north to the border with Switzerland to the south.

The Eastern Front.

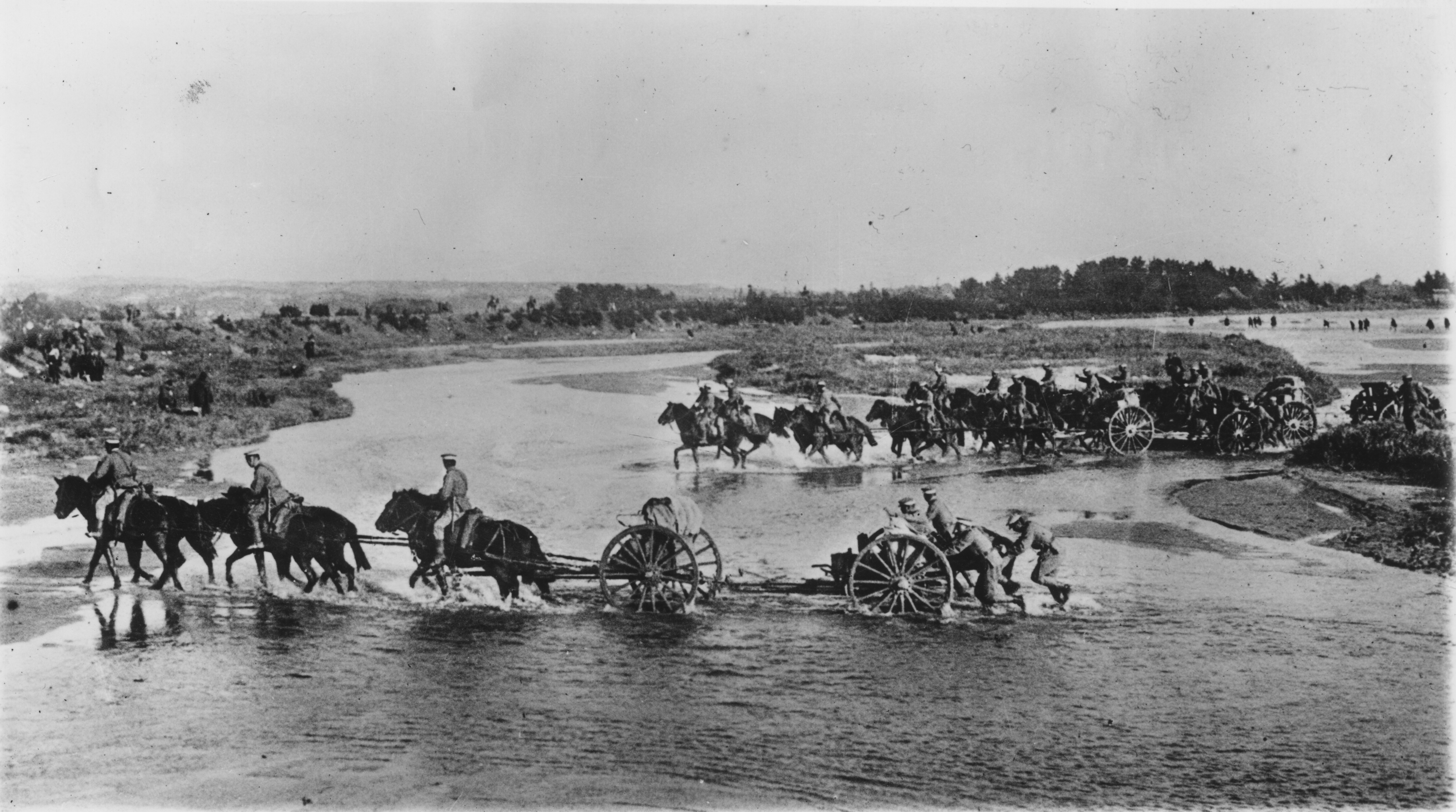

Russia mobilized on the Eastern Front more quickly than Germany expected. By late August 1914, two Russian armies had pushed deeply, along separate paths, into the German territory of East Prussia.

Despite being outnumbered, the German army inserted itself between the two Russian groups. By August 31, the Germans had encircled and destroyed one Russian army in the Battle of Tannenberg. They then chased the other Russian army out of East Prussia in the Battle of the Masurian Lakes. The Russians suffered about 250,000 casualties in the two battles. The victories made heroes of the commanders of the German forces in the east— Paul von Hindenburg and Erich Ludendorff .

Austria-Hungary had less success on the Eastern Front. By the end of 1914, Austria-Hungary’s forces had attacked Serbia three times with little success. Farther north, Russia had captured much of the Austro-Hungarian province of Galicia (now part of Poland and Ukraine). By early October, a bloodied Austro-Hungarian army had retreated into its own territory.

Fighting elsewhere.

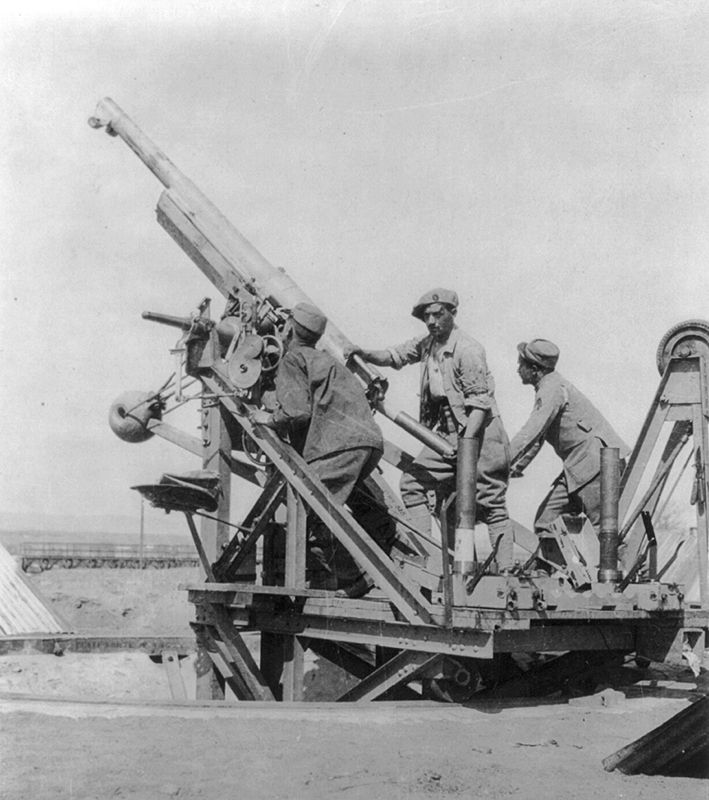

At the end of October 1914, the Ottoman Empire entered the war as a German ally. Ottoman ships bombarded Russian ports on the Black Sea. Ottoman troops then invaded Russia through the Caucasus Mountains. Fighting later broke out in the Ottoman territories on the Arabian Peninsula and in Mesopotamia (now mostly Iraq), Palestine, and Syria.

The United Kingdom stayed in control of the seas following two naval victories over Germany in 1914. The British then kept Germany’s surface fleet confined to its home waters for most of the war. As a result, Germany relied heavily on submarine warfare.

In late August 1914, Japan declared war on Germany, bringing World War I to Asia. The Japanese took several German islands in the Pacific Ocean. Troops from Australia and New Zealand seized other German colonies in the Pacific. By mid-1915, most of Germany’s empire in Africa had fallen to British forces. However, fighting continued in German East Africa (now Tanzania) for two more years.

The deadlock on the Western Front

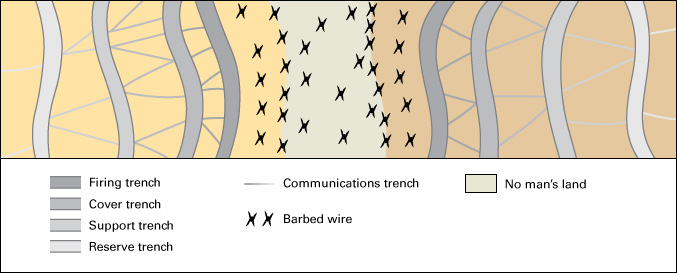

By 1915, the opposing sides had dug themselves into a system of trenches that zigzagged along the Western Front. Modern weapons caused horrible casualties as each side launched attacks against enemy trenches. The attacks failed to push through enemy lines, but armies continued to adapt and innovate.

Trench warfare.

The typical front-line trench was about 6 to 8 feet (1.8 to 2.4 meters) deep and wide enough for two men to pass. Dugouts in the sides of the trenches protected soldiers from enemy fire. Support trenches ran behind the front-line trenches. Off-duty soldiers lived in dugouts in the support trenches. Troops and supplies moved to the battlefront through a network of perpendicular communications trenches.

Barbed wire and sand bags helped protect the front-line trenches from attacks and gunfire. Field artillery shot from behind the support trenches. Between the enemy lines lay a stretch of ground called no man’s land. No man’s land ranged in width from less than 30 yards (27 meters) to more than 1 mile (1.6 kilometers). Artillery fire tore up the earth, making it difficult for soldiers to cross no man’s land during an attack.

Soldiers served at the front line from a few days to a week. They then rotated to the rear, where training and various tasks took much of their time. Except during an attack, life fell into a routine. Some soldiers stood guard. Others repaired the trenches or kept telephone lines in order. Still others brought food from behind the battle lines. At night, patrols fixed the barbed wire and tried to get information about the enemy.

Life in the trenches was miserable. The smell of dead bodies lingered in the air. Rats, lice, and filth were constant problems. Soldiers had trouble keeping dry, especially in water-logged areas of Belgium.

Trench warfare gave artillery gunners fixed targets. Both sides would bombard the enemy’s front-line trenches with artillery fire before launching an offensive (assault). This tactic helped clear the way for the infantry. But it also gave away the advantage of surprise. As attacking infantry pressed deeper into enemy territory, the troops drew farther away from their supporting artillery and closer to the enemy’s artillery. Artillery killed more soldiers in World War I than any other weapon.

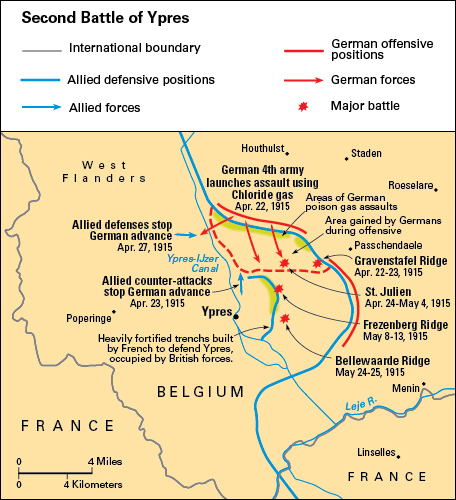

Both the Allies and Central Powers developed new weapons in hopes of breaking the deadlock. In April 1915, the Germans released poison gas against Allied troops during the Second Battle of Ypres . The Allies also began to use poison gas. Gas masks —sometimes ineffective—became necessary equipment in the trenches. Another new weapon, the flame thrower , shot out a stream of burning fuel.

The Battle of Verdun.

In early 1916, Falkenhayn, chief of the German General Staff, was focused on the defeat of France. He assumed France’s defeat would force the United Kingdom out of the war. Germany would then be free to concentrate on Russia in the east. Falkenhayn’s strategy was to “bleed France white”—in other words, to cause such horrible casualties that France would be forced to surrender. He chose to attack Verdun, a city of great historic and strategic value to France. The French would defend it at all cost.

Germany launched a massive attack on Verdun on February 21. For months, French defenses held the city against overwhelming force. However, a number of key positions—including forts Douaumont and Vaux—fell to the German onslaught. As the Battle of Verdun dragged into summer, both sides suffered major casualties. Having failed to break through the line of defense, Falkenhayn reduced his efforts.

At the end of August, Hindenburg and Ludendorff—the German heroes of the Eastern Front—replaced Falkenhayn on the Western Front. Hindenburg became chief of the General Staff. Ludendorff, his top aide, planned a defensive German strategy. In the autumn, repeated French attacks regained the lost forts. By battle’s end in December, the lines were almost exactly where they had been at the start.

General Henri Philippe Pétain had organized the defense of Verdun. France hailed him as a hero. However, the Battle of Verdun came to symbolize the destructiveness of modern war. French and German casualties numbered more than 700,000, with more than 200,000 dead. Verdun and the surrounding area were almost completely destroyed.

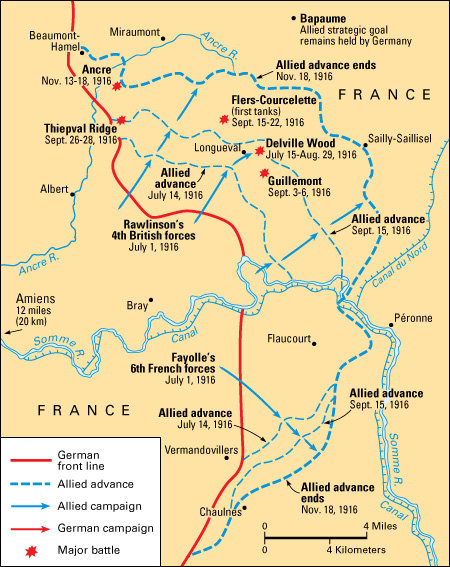

The Battle of the Somme.

In the summer of 1916, the Allies planned a major offensive near the Somme River in France. It was to be a joint Franco-British assault, but British troops made up the bulk of the Allied force. Having suffered terrible casualties, the British had introduced conscription earlier in the year. British General Douglas Haig led the troops.

The British and French attacked on the morning of July 1. German machine guns and artillery slaughtered many of the attacking soldiers. Within hours, the United Kingdom had suffered nearly 60,000 casualties—its worst loss ever in one day of battle. Despite heavy losses for tiny gains, Haig pressed on with the attack.

Fierce fighting went on into the fall. In September, the British army introduced the first tanks. However, the early tanks were too unreliable and too few in number to make a major difference in the battle. Haig finally halted the attack in November.

The Battle of the Somme caused more than 1 million casualties. They included as many as 650,000 Germans, about 420,000 British, and nearly 200,000 French. The attack advanced the Allies just 7 miles (11 kilometers). Like Verdun, the Somme came to symbolize the horrors of trench warfare on the Western Front.

The war on other fronts

During 1915 and 1916, World War I spread to Bulgaria , Greece , Italy , and Romania . Allied military leaders believed that the fighting on new battlefronts would break the deadlock on the Western Front. However, the war’s expansion initially led to additional conquests for the Central Powers.

The Italian Front.

Although a member of the Triple Alliance with Austria-Hungary and Germany, Italy had stayed out of the war in 1914. Italy claimed that it had no obligation to honor the agreement because Austria-Hungary had not gone to war in self-defense. In May 1915, Italy entered World War I on the side of the Allies. In a secret treaty, the Allies promised to give Italy large chunks of Austro-Hungarian territory after the war. In return, Italy promised to attack Austria-Hungary.

The Italians, led by General Luigi Cadorna, hammered away at Austria-Hungary for two years without success. In a series of battles along the Isonzo River, Italy suffered enormous casualties but gained little territory. The Allies had hoped that the Italian Front would draw German troops away from the Russian front. Instead, the front drew Allied troops, who rushed to help Italy, away from the Western Front. Cadorna’s leadership was widely criticized.

The Dardanelles and Gallipoli.

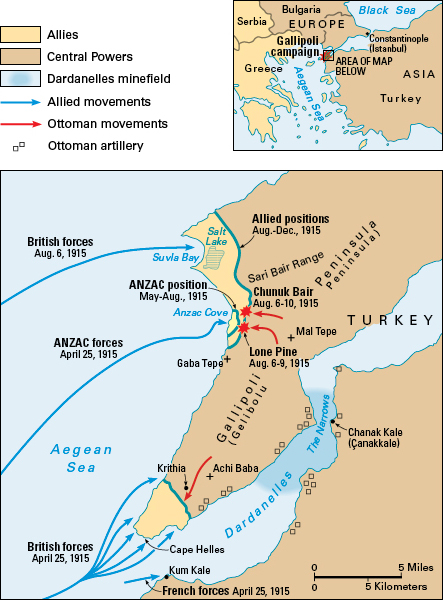

After World War I began, the Ottoman Empire closed the waterway that connected the Aegean Sea and the Black Sea. The closure blocked an important sea route into southern Russia. In February and March 1915, British and French warships attacked the Dardanelles , a strait that formed part of the waterway. The Allies hoped to open the supply route to Russia, while also trying to force the Ottomans out of the war. However, underwater mines and shore-based artillery halted the naval assault.

After the naval assault failed, the Allies planned to seize the Gallipoli Peninsula. The peninsula juts into the Aegean Sea at the entry to the Dardanelles.

Allied troops landed on Gallipoli on April 25, 1915. The Gallipoli landing was at the time the largest military landing in history. It involved about 75,000 soldiers from Australia , France, New Zealand , and the United Kingdom. The main Allied force landed at the tip of the peninsula. Australian and New Zealand Army Corps ( ANZAC ) forces landed at Gaba Tepe, more than 10 miles (16 kilometers) north. That area later became known as Anzac Cove.

Soon after the landing, Ottoman and Allied forces became locked in brutal trench warfare. The Ottomans, having been alerted by naval attacks, had strengthened their defenses on the peninsula. In August, additional Allied troops landed at Suvla Bay, to the north. Still, the Allies were unable to penetrate far inland. In December, the Allies began evacuating their troops. They had suffered some 250,000 casualties in the region. The waterway remained closed.

April 25, the date of the Gallipoli landing, became a patriotic holiday in Australia and New Zealand. Called Anzac Day , the holiday honors Australians and New Zealanders who have served in the armed forces.

Eastern Europe.

The Eastern Front stretched nearly 1,000 miles (1,600 kilometers) from the Baltic Sea to the Black Sea. Battlefields were huge. Unlike the deadlocked Western Front, the Eastern Front sometimes moved hundreds of miles at a time. In May 1915, the armies of Germany and Austria-Hungary broke through Russian lines in Galicia (a region of present-day Poland and Ukraine). The Russians retreated about 300 miles (480 kilometers).

A failed Russian attack in March 1916 resulted in over 100,000 casualties. Russian General Alexei Brusilov then planned a massive offensive for that summer. The offensive was planned in conjunction with the Battle of the Somme in the West. In June and July 1916, Brusilov’s army drove Austria-Hungary’s forces back as far as 50 miles (80 kilometers). Russia captured about 200,000 prisoners. To stop the assault, Austria-Hungary shifted troops from the Italian Front to the Eastern Front. The Russian offensive nearly knocked Austria-Hungary out of the war. However, it also exhausted Russia. Each side suffered about 1 million casualties.

Bulgaria joined the Central Powers in attacking Serbia in October 1915. It hoped to recover land it had lost in the Second Balkan War. In an effort to aid Serbia, the Allies landed troops in Thessaloniki (Salonika), Greece. However, the troops never reached Serbia. By November, Serbia was overrun by the Central Powers.

Romania joined the Allies in August 1916. The Romanians hoped to take advantage of Brusilov’s victory and potentially gain Austro-Hungarian territory in the event of an Allied victory. But Germany attacked Romania and destroyed most of the Romanian army. By the end of 1916, Germany controlled Romania’s valuable wheat and oil.

The war at sea.

With control of the seas, the British Royal Navy was able to blockade German ports—that is, it was able to patrol the coasts and keep Germany from receiving supplies. By 1916, the blockade had caused shortages of food and other goods in Germany. The shortages caused unrest throughout the country.

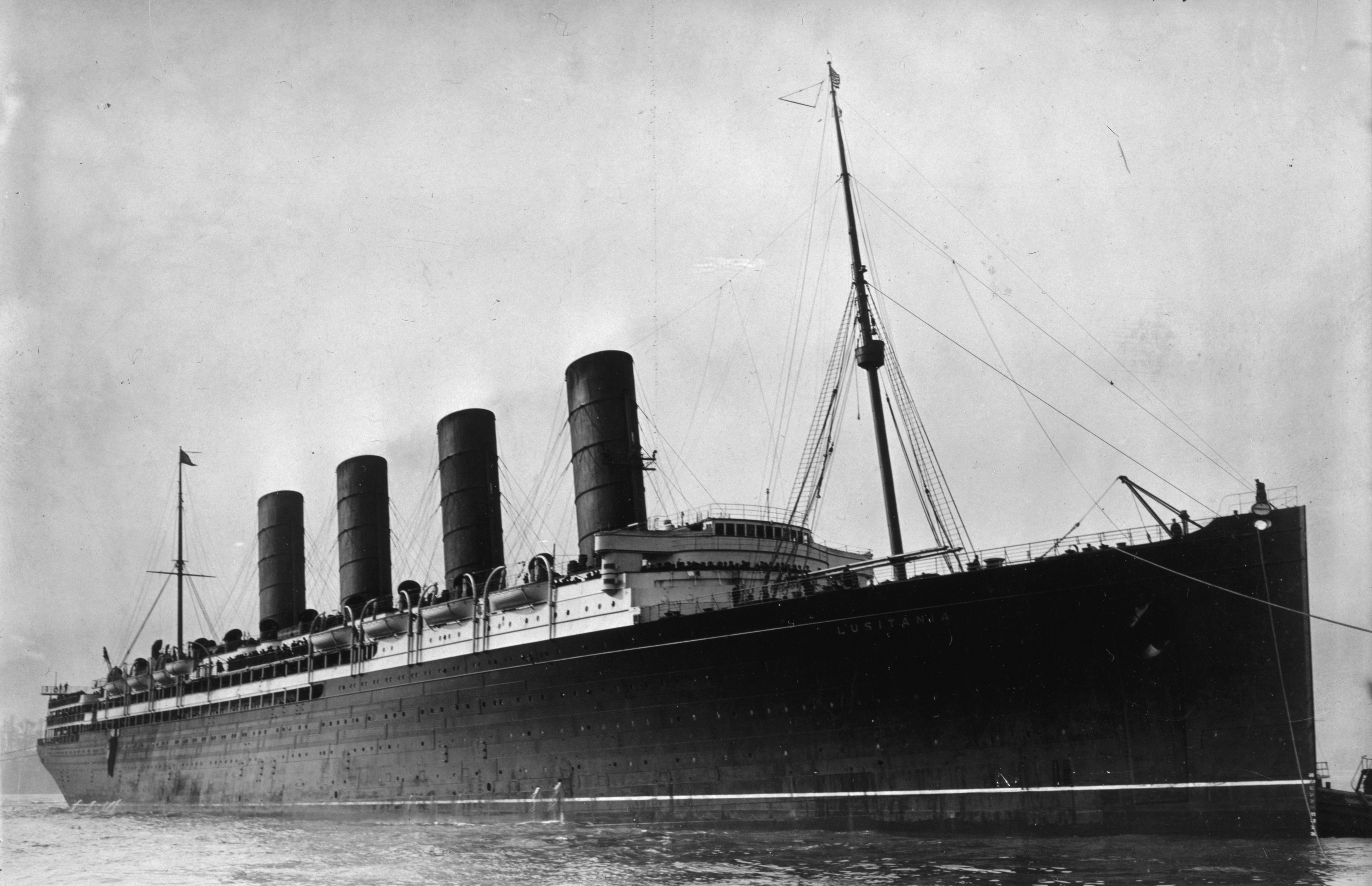

Beneath the blockade, Germany launched a fleet of submarines , called Unterseeboote, or U-boats. In February 1915, German U-boats began attacking ships bound for the United Kingdom or Ireland. The submarine attacks caused much loss of life. They also interfered with the shipment of merchant goods and war supplies.

On May 7, 1915, a German U-boat torpedoed the British passenger liner Lusitania off the coast of Ireland. The attack killed 1,201 passengers, including 128 Americans. The sinking of the Lusitania led U.S. President Woodrow Wilson to urge Germany to give up unrestricted submarine warfare. In September, Germany agreed not to attack neutral or passenger ships.

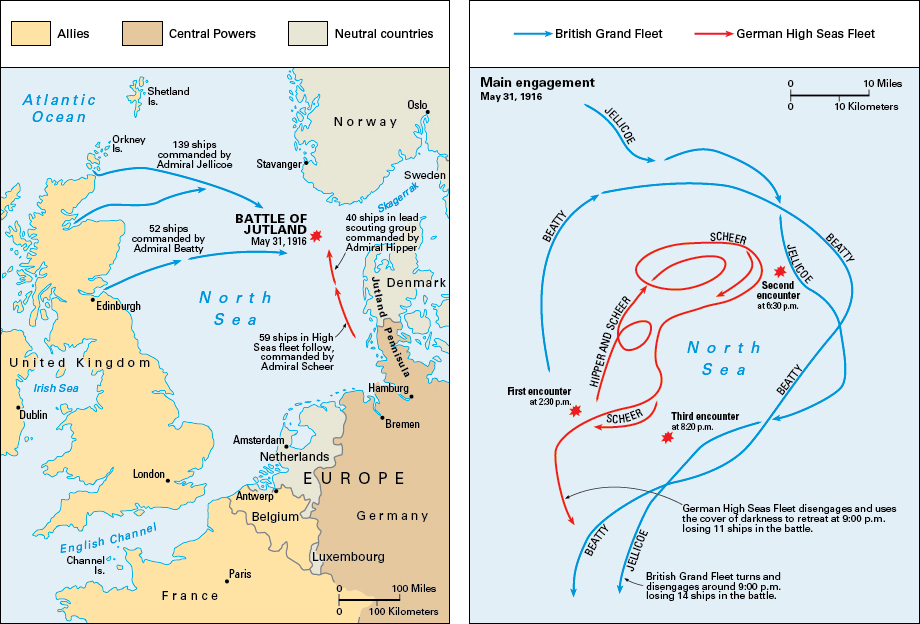

The only major surface encounter between German and British warships was the Battle of Jutland . The battle took place off the coast of Denmark on May 31 and June 1, 1916. Admiral Sir John Jellicoe commanded a British fleet of 150 warships. Admiral Reinhard Scheer commanded a smaller German fleet of 99 ships. Still, Jellicoe acted cautiously, as a British loss would have given Germany control of the seas.

The Germans destroyed more enemy ships than the British did in the Battle of Jutland. However, by battle’s end, the Germans had lost a greater percentage of their smaller navy. About 7,000 British sailors were killed and wounded, more than twice what the Germans lost. But the United Kingdom maintained control of the seas

The war in the air.

When World War I broke out in 1914, airplanes were still a recent invention. At first, the Allies and Central Powers used rickety wooden planes for observation. Before long, each side developed stronger planes equipped with machine guns. These fighter planes could destroy enemy planes and observation balloons. Later, both sides began using airplanes to drop bombs. Pilots in some early bombing flights dropped small bombs by hand from open cockpits.

Air combat increased sharply throughout the war. In 1915, Anthony Fokker , a Dutch designer working for Germany, developed a machine gun that was timed to fire between an airplane’s revolving propeller blades. This invention enabled pilots to fire their guns more accurately while flying. Other innovations, such as new metal frames and stronger engines, made air combat more intense—and more deadly. Soldiers watched from the trenches as enemy fighters battled high above in dogfights. Control of the air became crucial to the success of ground attacks.

Flying was incredibly dangerous during the war, and most pilots had short careers. If a pilot flew long enough, he might shoot down five or more enemy planes to become an ace . Many aces became national heroes. Germany’s Baron Manfred von Richthofen —commonly known as the Red Baron—shot down 80 planes, more than any other pilot. Other aces included Billy Bishop of Canada, René Fonck of France, Edward Mannock of the United Kingdom, and Eddie Rickenbacker of the United States.

In 1915, Germany began bombing London and other British cities from airships called zeppelins. By 1917, both sides planned major bombing offensives using large new aircraft called bombers .

Later stages

In early 1917, Allied military leaders hoped that simultaneous offensives on all fronts could win the war. However, the Germans had improved their western defenses and withdrawn to a strongly fortified new battle line in northern France. The line was known as the Siegfried Line , or Hindenburg Line. Germany’s new defenses shortened the Western Front, concentrating firepower and freeing more German troops for the Eastern Front.

Also during early 1917, a series of events drew the United States—which had been neutral—into the war. The American entry into the conflict greatly boosted the Allied numbers and helped bring about the war’s end.

Allied struggles.

In December 1916, General Robert Nivelle, a French hero at Verdun, had replaced General Joffre as commander in chief of the French forces. Nivelle planned a major offensive for April 1917 near the Aisne River. He ignored Germany’s pullback to the Siegfried Line and predicted a French victory.

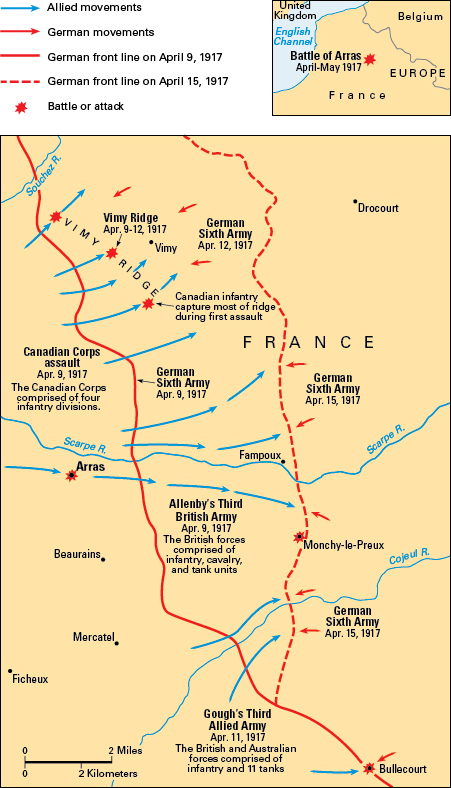

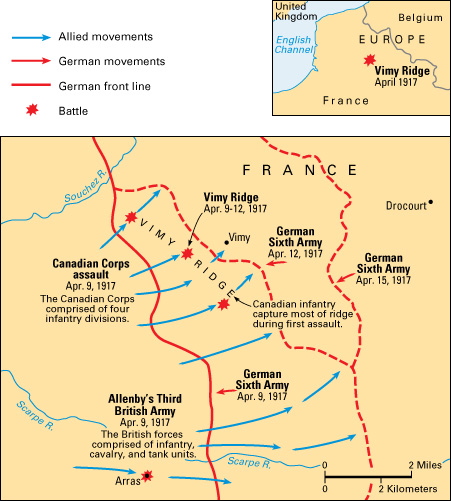

A week before the Nivelle Offensive, the British Army launched an attack at Arras, in northern France. The attack was designed to pull German reserves away from the Aisne River. The Arras attack had some success. As the British attacked Arras, Canadian troops took Vimy Ridge , a strategic hill nearby. The Canadian victory was a powerful morale booster for the Allies. Word of the United States’ entry into the war further boosted Allied confidence.

The Nivelle Offensive started on April 16, 1917, but it quickly turned into a disaster. The French suffered some 40,000 casualties on the first day alone. Nivelle, his nerve unshaken, continued the offensive into May, when it was finally called off. Nearly 190,000 French soldiers were killed, wounded, or captured in the failed attack, along with more than 150,000 Germans.

The failure of the offensive led to mutinies among the French forces. The troops had tired of the bloodshed and miserable conditions of the Western Front. General Henri Philippe Pétain replaced Nivelle in May. Pétain improved the soldiers’ living conditions and restored order. He promised that France would remain on the defensive until the arrival of trained replacements, better weapons and tactics, and large numbers of U.S. troops.

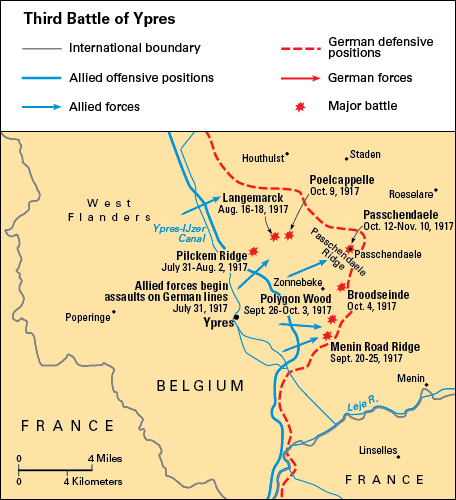

As the French recovered, British Field Marshall Haig hoped that an offensive near Ypres would break the German lines. The Third Battle of Ypres , also known as the Battle of Passchendaele, began on July 31, 1917. Bombardment and heavy rains turned the battlefield into a mucky swamp. Fighting continued under horrible conditions for more than three months. The Allies advanced less than 6 miles (10 kilometers), taking the Passchendaele ridge on November 6. There were about 250,000 Allied and 200,000 German casualties.

In late 1917, the Allied position looked bleak. In October, Italy had been driven back by a combined German and Austro-Hungarian attack in the Battle of Caporetto. In November, a British tank assault met with brief success at Cambrai, France, but the Germans quickly regained their lost ground. That same month, a revolution threatened to take Russia out of the war.

Revolution in Russia.

The Russian people suffered greatly during World War I. By 1917, many of them could no longer endure the millions of Russian casualties and shortages of food and fuel. They blamed Czar Nicholas II and his advisers for the country’s problems. Early in 1917, an uprising in Petrograd (now St. Petersburg) forced Nicholas from the throne. Still, the new democratic government continued the war effort.

In April 1917, Germany helped Russian revolutionary V. I. Lenin , who had been exiled to Switzerland, return to his homeland. Seven months later, Lenin led a Communist uprising that gained control of Russia’s government. As Russia’s new ruler, Lenin immediately called for peace talks with Germany. Russia and the Central Powers signed the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (now Brest, Belarus) on March 3, 1918. World War I had ended on the Eastern Front.

Germany dictated harsh peace terms to Russia. The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk forced Russia to give up Finland, Ukraine, and Bessarabia (now mostly in Moldova). Germany thus gained access to badly needed wheat and oil. The treaty also gave to Germany parts of Poland that had been ruled by Russia and the Baltic States (Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania). The end of the fighting on the Eastern Front made millions of German troops available for the Western Front.

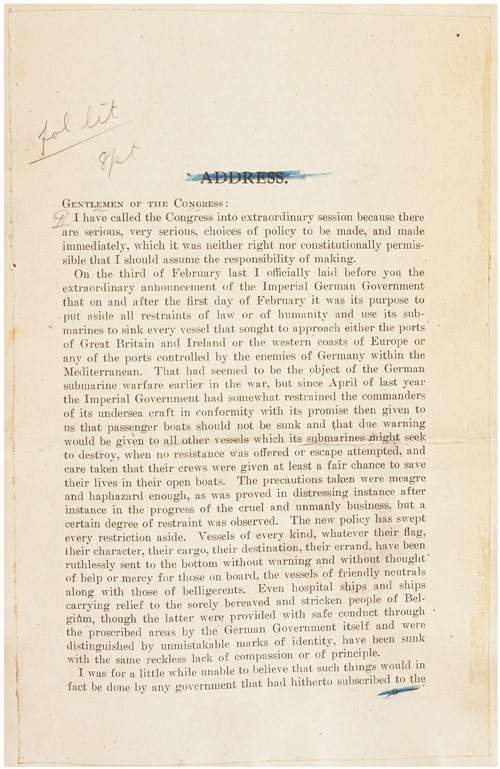

The United States enters the war.

At the start of World War I, President Woodrow Wilson declared the neutrality of the United States. Most Americans initially opposed U.S. involvement in a European war. However, Germany’s sinking of the Lusitania and other actions against civilians drew American sympathies to the Allies.

Several events early in 1917 persuaded the U.S. government to enter World War I. In February, Germany returned to unrestricted submarine warfare. German military leaders knew this decision might bring the United States into the war, but they believed they could win the war by cutting off British supplies. Germany hoped to win the war before the United States could fully mobilize and land an army in Europe.

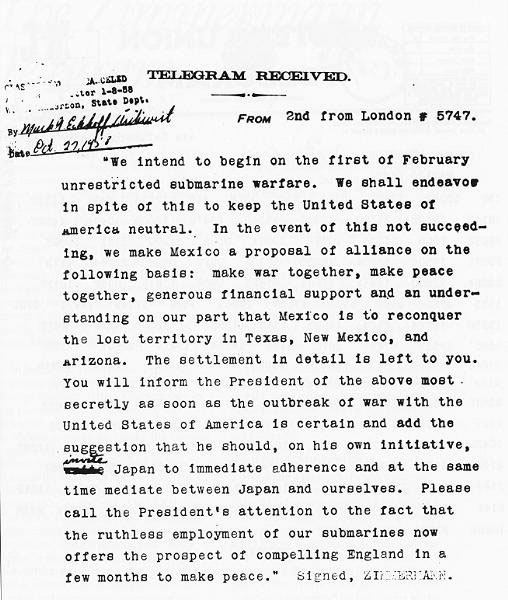

Tension between the United States and Germany further increased as a result of the ” Zimmermann telegram .” The telegram was a message from Germany’s foreign minister, Arthur Zimmermann, to the German ambassador to Mexico. The British intercepted and decoded the message in January and relayed the message to the United States in late February. The message revealed a German plot to persuade Mexico to go to war against the United States. News of the plot infuriated an American public already upset by U-boat sinkings of several U.S. cargo ships.

Wilson finally called for war, saying “the world must be made safe for democracy.” Congress declared war on Germany on April 6. However, the U.S. military at that time lacked experience, modern weapons, and a sufficient number of soldiers.

Mobilization.

The United States entered World War I unprepared for battle. Strong antiwar feelings had hampered efforts to prepare for war. After the declaration of war, the government tried to stir up enthusiasm. Government propaganda presented the war as a battle for liberty and democracy. As public opinion shifted, people who still opposed the war faced increasingly hostile reactions. They could even be brought to trial under wartime laws forbidding statements considered harmful to the progress of the war.

American government agencies directed the nation’s economy toward the war effort. President Wilson put financier Bernard M. Baruch in charge of the War Industries Board. The board helped convert commercial factories into producers of war materials. The Food Administration, headed by businessman Herbert Hoover , controlled the prices, production, and distribution of food. Americans observed “meatless” and “wheatless” days so that food could be sent to Europe.

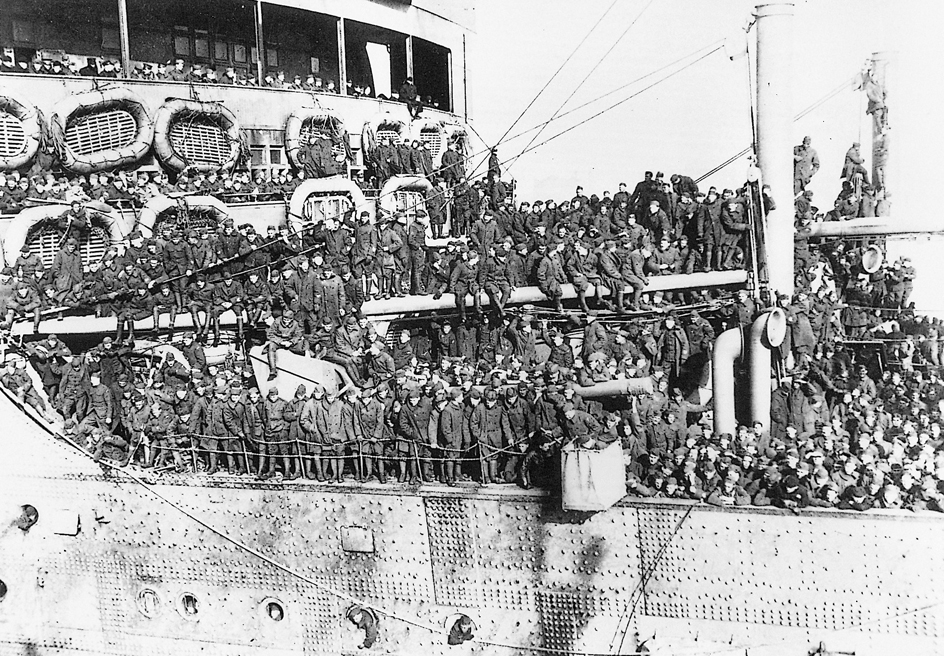

The United States entered the war with a regular army of only about 128,000 soldiers. The military grew quickly, however, as a result of conscription. The military draft brought in huge numbers of recruits. In addition, many people volunteered for service. Women signed up as nurses or took on various noncombat duties. By the end of the war, the U.S. armed forces had almost 5 million men and women. Of that number, nearly 3 million men had been drafted. Because the troops were so urgently needed, many American recruits were rushed overseas with little training in the ways of war.

Before U.S. help could reach the Western Front, the Allies had to overcome the U-boat threat in the Atlantic. In May 1917, the United Kingdom began to use a convoy system. In this system, cargo ships went to sea in large groups escorted by warships . The system was a success. Allied shipping losses dropped sharply, and ships were able to carry American troops safely to Europe.

American troops in Europe.

The U.S. Army soldiers who were sent to Europe made up the American Expeditionary Forces ( A.E.F. ). Commanded by General John J. Pershing , the troops began arriving in France in July 1917. The A.E.F. entered combat on the Western Front in October. By July 1918, there were more than 1 million U.S. troops in Europe. In the end, about 2 million American soldiers reached the continent.

In November 1917, Allied leaders formed the Supreme War Council, a central group to plan strategy. The Allies planned to remain on the defensive until significant numbers of U.S. troops could reach the Western Front. They wanted the Americans to serve as replacements and to fill out the battered Allied ranks. However, Pershing wanted the A.E.F. to remain independent, largely for political reasons. He also believed his troops would be weakened if they were dispersed among the European forces. The argument was the major wartime dispute between the Europeans and their American ally. Pershing held firm, though at times he lent troops to France and the United Kingdom.

The last campaigns

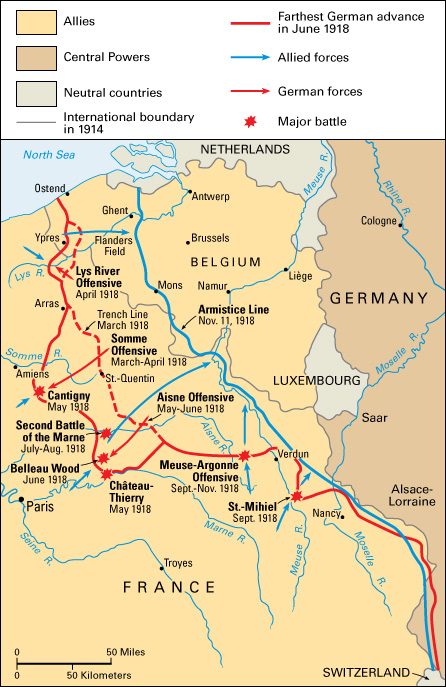

The end of fighting on the Eastern Front had enabled the Germans to concentrate on the Western Front. General Ludendorff helped shape an aggressive German strategy. He hoped to secure victory before the Americans could reach the front in large numbers. Using new artillery and infantry methods, Germany launched five offensives during the spring and summer of 1918. The attacks broke the long-running deadlock on the Western Front.

German offensives.

In the first offensive, the Germans struck a British position near Saint-Quentin, in the Somme River Valley, on March 21. By March 26, the British troops had retreated about 30 miles (50 kilometers). In late March, the Germans started bombarding Paris. They fired huge guns that could hurl shells up to 75 miles (120 kilometers). Allied leaders soon appointed French General Ferdinand Foch as supreme commander of the Allied forces on the Western Front.

A second German offensive began on April 9. German troops attacked along the Lys River in Belgium, but British troops fought back stubbornly. Ludendorff called off the attack on April 30. The Allies suffered heavy losses in the first two offensives. However, German casualties were just as great.

A third German attack began on May 27 near the Aisne River. By May 30, German troops had reached the Marne River. American soldiers helped French units stop the German advance at the town of Château-Thierry, less than 50 miles (80 kilometers) northeast of Paris.

In June, a fourth German offensive against Allied troops near Compiègne gained little ground. That same month, U.S. troops drove the Germans out of Belleau Wood, a forested area near the Marne. American forces had begun playing a greater role in the fighting.

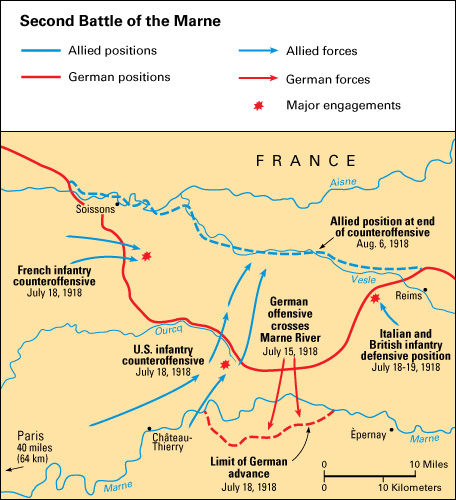

On July 15, the Germans launched their fifth and final offensive, crossing the Marne east of Paris. French troops, supported by American, British, and Italian forces, stopped the German advance. On July 18, General Foch ordered an Allied counterattack near the town of Soissons. The counterattack caught the Germans by surprise and marked the turning point of World War I. The attack stopped on August 6. The victory at the Second Battle of the Marne set the stage for the final Allied offensives of World War I.

The Allied advance.

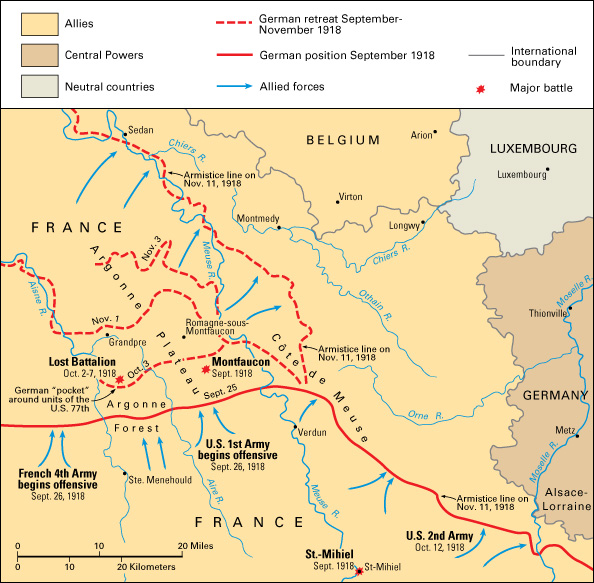

The Allies began a steady advance along the length of the Western Front. On August 8, British and French troops attacked the Germans near Amiens. By early September, Germany had lost all the territory it had gained since the spring. In mid-September, General Pershing led U.S. forces to victory at Saint-Mihiel.

The Meuse-Argonne Offensive , also called the Battle of the Argonne Forest, began on September 26. Brutal fighting in the area between the Argonne Forest and the Meuse River carried on into November. The offensive was the largest American battle of World War I, with about 1.2 million U.S. troops participating. It was a crucial part of the final Allied push that forced Germany’s surrender.

During the spring, summer, and fall campaigns of 1918, both the Allies and Central Powers suffered more than 1.5 million casualties. The Allies, with a deep well of American troops, could sustain the losses. The Central Powers could not.

The fighting ends.

The Allies won victories on all fronts in the fall of 1918. Bulgaria surrendered on September 29. British forces under General Edmund Allenby defeated Ottoman forces in Palestine and Syria. On October 30, the Ottoman Empire signed an armistice (agreement to end fighting). The last major battle in Italy saw Italian troops, with British and French support, smash the Austro-Hungarians at Vittorio Veneto. Austria-Hungary signed an armistice on November 3.

General Ludendorff recognized that the German army could not recover and demanded an armistice in October. German civilians suffered food shortages caused both by the naval blockade and by poor government. Strikes and riots turned into revolution. Mutiny erupted in the German navy. Kaiser Wilhelm II, Germany’s ruler, gave up his throne on November 9 and fled to the Netherlands.

Allied leaders met with German representatives in a railroad car in the Compiègne Forest in northern France. In the early morning on November 11, the Germans accepted the armistice terms demanded by the Allies. Germany agreed to evacuate the territories it had taken during the war. It also agreed to return areas of Alsace-Lorraine that had been taken from France in 1871. Germany surrendered large numbers of weapons, ships, and other war materials. It also agreed to allow the Allied powers to occupy German territory across the Rhine River.

At 11 a.m. on Nov. 11, 1918, General Foch ordered an end to the fighting on the Western Front. World War I was over.

Consequences of the war

Destruction and casualties.

World War I caused incredible destruction. About 9 million soldiers died as a result of the war, far more than in any previous conflict. About 21 million troops were wounded. Germany and Russia each suffered nearly 2 million battle deaths—more than any other country. Suffering continued well after the armistice as societies struggled to care for widows, orphans, and badly wounded soldiers.

Improved artillery, machine guns, and other advanced weapons proved deadlier than earlier designs. When generals used old tactics, such as bayonet charges, the new weaponry slaughtered their troops. Many lives were lost as armies tried to adjust to the new weapons.

Nobody knows how many civilians died of disease, starvation, and other war-related causes. Some historians believe the war killed as many civilians as it did soldiers. In the Ottoman Empire in 1915, in what many scholars consider to be genocide (the systematic killing of a group), about 11/2 million Armenians were killed or died from lack of water and food. A worldwide influenza epidemic—the Spanish flu —killed many millions more in 1918 and 1919.

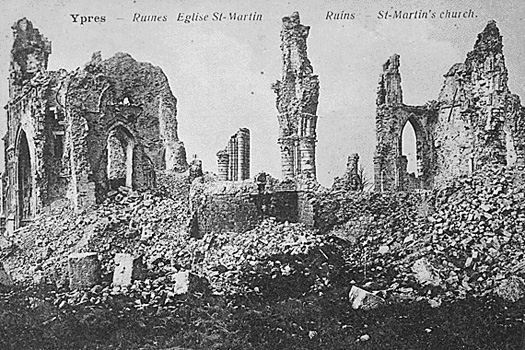

Property damage in World War I was greatest in France and Belgium. Many areas of the Eastern Front were also devastated. Armies destroyed farms and villages as they passed through them or dug in for battle. The fighting wrecked factories, bridges, and railroad tracks. Artillery shells, trenches, and chemicals made much of the land along the Western Front barren.

Economic consequences.

World War I cost the fighting nations a total of about $337 billion (in 1918 dollars). By 1918, the war was costing about $10 million per hour. Economists estimate that fighting the war consumed about 50 percent of the economic output of Germany and France in 1918. In contrast, Canada and the United States spent about 17 percent of their economic output on the war that year.

Nations raised part of the money to pay for the war through taxes. But most of the money came from borrowing, which created huge debts. Governments borrowed from citizens by selling war bonds. The Allies also borrowed heavily from the United States. In addition, most governments printed extra money to meet their needs. The increased money supply caused severe inflation (price increases) and contributed to the Great Depression of the 1930’s.

The problem of war debts lingered after World War I ended. The Allies attempted to reduce their debts by demanding reparations (payments for war damages) from the Central Powers, especially Germany. Reparations became a source of contention for many years.

World War I severely disrupted the economies of the warring nations. Some businesses shut down after workers left for military service. Other businesses shifted to the production of war materials. To direct production toward the war effort, governments took greater control over the economy than ever before. After the war, most people wanted a return to private enterprise. However, some people expected governments to continue to solve economic problems.

The countries of Europe had poured their resources into World War I, and they came out of the war exhausted. In many European countries, returning soldiers had difficulty finding jobs. In addition, the nations of Europe, having been occupied with the production of war goods, lost many of the markets for their exports. The United States and other countries that had played a smaller role in the war emerged with increased economic power.

Political consequences.

World War I shook the foundations of several governments. Democratic governments in the United Kingdom and France withstood the stress of the war. However, four long-standing monarchies toppled. The first monarch to fall was Czar Nicholas II of Russia in 1917. Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany and Emperor Charles I of Austria-Hungary left their thrones in 1918. The Ottoman sultan, Muhammad VI, fell in 1922.

The collapse of old empires led to the creation of new countries in the years after World War I. The prewar territory of Austria-Hungary became the independent republics of Austria, Hungary, and Czechoslovakia , as well as parts of Italy, Poland, Romania, and Yugoslavia . Russia and Germany gave up territory to Poland. Finland and the Baltic States—Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania—gained independence from Russia. Most Arab lands in the Ottoman Empire were placed under the control of France and the United Kingdom. The rest of the Ottoman Empire became Turkey .

World War I gave the Communists an opportunity to seize power in Russia. Revolutionary movements also gained strength elsewhere in Europe, but Communist governments did not take hold.

Social consequences.

World War I brought enormous changes in society. The deaths of so many people, both soldiers and civilians, left deep psychological scars on the survivors. Millions of people were uprooted. Many people who fled war-torn areas returned to find their houses, farms, or villages destroyed. Changes in governments and national borders, especially in central and eastern Europe, produced numerous refugees.

Many people chose not to resume their old way of life after the war. Urban areas grew as peasants settled in cities instead of returning to farms. Women who had filled jobs in offices and factories grew accustomed to their new-found independence. After the war, many countries, including the United States, granted women the right to vote.

The distinction between social classes began to blur as a result of World War I. Society became more democratic. The upper classes, which had traditionally governed, lost some of their power and privilege. People of all classes had faced the same horrors in the trenches. Those who had bled and suffered for their country came to demand a say in running it.

Finally, World War I transformed attitudes. Middle- and upper-class Europeans lost the confidence and optimism they had felt before the war. Many people began to question long-held ideas. The destruction of the war led many people to doubt their belief in the superiority of European civilization.

The peace settlement

In January 1919, representatives of the victorious Allied nations gathered in Paris to draw up a peace settlement. The peacemakers eventually produced a series of agreements that officially ended the war and greatly reshaped Europe.

The Paris Peace Conference

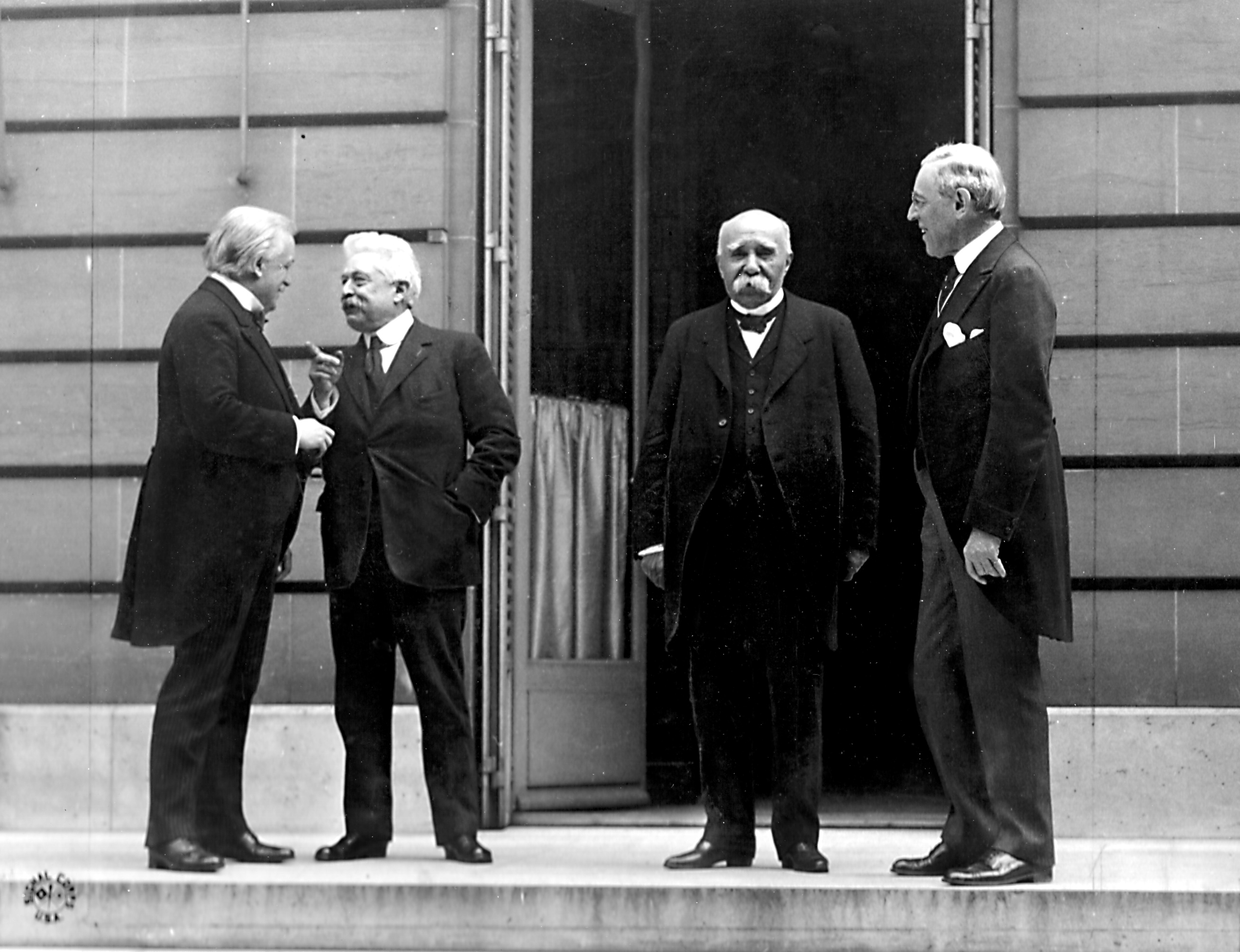

included representatives from 32 nations. Committees worked out specific proposals, but four heads of government made the key decisions. These “Big Four” were U.S. President Woodrow Wilson, British Prime Minister David Lloyd George , French Premier Georges Clemenceau , and Italian Prime Minister Vittorio Orlando . Orlando, however, had far less influence than the other three.

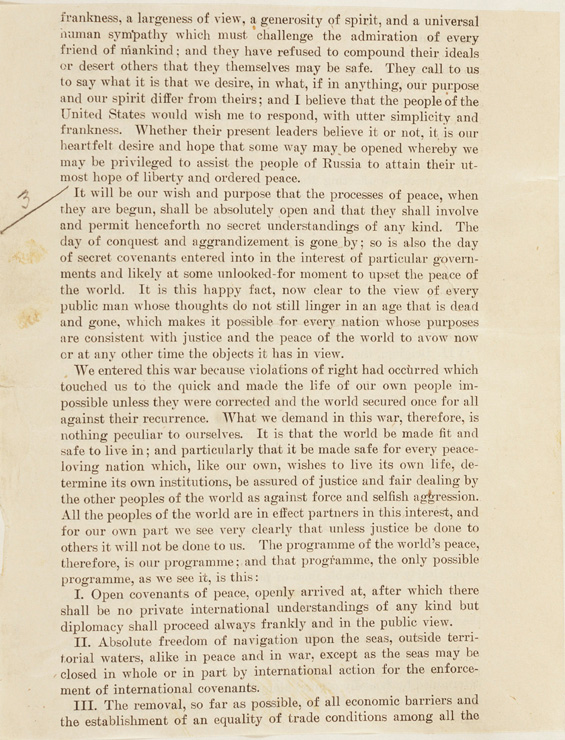

President Wilson famously outlined his peace goals in the “ Fourteen Points .” This set of principles included openness in international agreements, arms reductions, the removal of barriers to trade, and the formation of a “general association of nations.” It also included _self-determination—_the idea that no ethnic group should be governed by a nation or state it opposes.

The Fourteen Points were popular at first, and Germany expected them to form the basis of the peace settlement. However, Wilson’s ideas met with increasing opposition from the Allies, as well as from rival politicians in the United States. The Paris Peace Conference soon turned contentious, as representatives largely disregarded the Fourteen Points. Allied leaders blamed Germany for the war and demanded severe punishment. Self-serving aims, such as gaining territory and preserving colonies, also clouded the conference.

Talks dragged on for months, and the resulting treaty became a patchwork of compromises. People on all sides had grave doubts about the terms of the agreement. Still, German representatives signed the treaty in the Palace of Versailles , near Paris, on June 28, 1919. The date was the fifth anniversary of the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand.

The Treaty of Versailles officially ended military actions against Germany. The peacemakers drew up separate agreements with the other Central Powers. The Treaty of Saint-Germain established peace with Austria in September 1919. Bulgaria signed the Treaty of Neuilly in November 1919. The Treaty of Trianon was finalized with Hungary in June 1920. The Ottoman Empire signed the Treaty of Sèvres in August 1920.

Treaty provisions.

The treaties that officially ended World War I stripped the Central Powers of territory and arms. The treaties also required the defeated powers to pay steep reparations. Germany blamed Russia’s mobilization for starting the war. However, the Allies forced Germany to accept sole responsibility.

Under the Treaty of Versailles, Germany lost large chunks of its former territory and all of its overseas colonies. France gained control of coal fields in Germany’s Saar Valley for 15 years. An Allied military force, paid for by Germany, was to occupy the west bank of the Rhine River for 15 years. Another clause in the treaty limited Germany’s armed forces. Still another required the country to turn over war materials, ships, livestock, and other goods to the Allies. A total sum for reparations was not set until 1921. Germany received a bill for about $33 billion (in 1921 dollars), though it evaded paying much of the debt.

The Treaty of Versailles also created several new international organizations, including the League of Nations . The League was an international association of countries that would work to maintain the peace.

The Treaty of Saint-Germain and the Treaty of Trianon reduced Austria and Hungary to less than one-third of their former area. The treaties recognized the independence of Czechoslovakia , Poland , and a kingdom that later became Yugoslavia . Those new states, along with Italy and Romania, received territory that had belonged to Austria-Hungary. The Treaty of Sèvres took Arabia, Lebanon, Mesopotamia (later renamed Iraq), Palestine, and Syria away from the Ottoman Empire. Bulgaria lost territory to Greece and Romania. Germany’s allies also had to reduce their armed forces.

The postwar world.

The settlements at the end of World War I disappointed both the victors and the defeated powers. The peacemakers had found it impossible to satisfy the hopes and ambitions of every country and national group. Smaller conflicts soon erupted in Russia, Poland, Turkey, and elsewhere, dashing hopes that World War I had been “the war to end all wars.”

In creating new borders within Europe, the peacemakers considered the wishes of national groups. However, territorial claims overlapped in many cases. For example, Romania gained an area of land with a large Hungarian population. Parts of Czechoslovakia and Poland were home to many Germans. Such arrangements heightened tensions between countries. At the same time, the Allies fueled resentment by failing to allow self-determination for many people in Africa, Asia, and the Middle East.

Certain borders created by the peace settlements made little economic sense. For example, the new countries of Austria and Hungary were too small and weak to support themselves. They had lost crucial resources and markets. Austria’s largely German population had wanted to unite with Germany, but the peacemakers refused to allow Germany to gain territory from the war.

Among the European Allies, the United Kingdom was the most content with the postwar arrangements. The nation had kept its empire and its control of the seas. However, the British worried that a weakened Germany and the Communist victory in Russia could upset the balance of power in Europe.

The French had succeeded in imposing harsh terms on Germany but not in safeguarding their country’s borders. They had lost their alliance with Russia, and they had failed to create new alliances with the United Kingdom and United States. Italy was unhappy with the postwar arrangements, as it gained less territory than it had been promised. Italian resentment toward the Allies and dissatisfaction with the country’s government eventually contributed to the rise of fascist leader Benito Mussolini .

In the United States, the Treaty of Versailles was unpopular. President Wilson was unable to rally support, and the Senate did not approve the agreement. As a result, the United States did not become a member of the League of Nations. Many Americans were not yet ready to accept the responsibilities of their country’s new power. They feared that the League would entangle the country in European disputes.

The terms of the Treaty of Versailles proved harsher than Germany had expected. Widespread bitterness over the agreement weakened Germany’s postwar government. During the 1930’s, Nazi leader Adolf Hitler gained power in Germany. Among other things, Hitler promised to defy the Treaty of Versailles and restore German power. The road to World War II had begun.