Yorktown, Siege of, was the last major military operation of the American Revolution (1775-1783). It took place in southeastern Virginia in September and October 1781. A combined American and French force besieged (surrounded) British troops at Yorktown, and the British surrendered on October 19. General George Washington led the American and French force. Lieutenant General Lord Charles Cornwallis led the British.

Background.

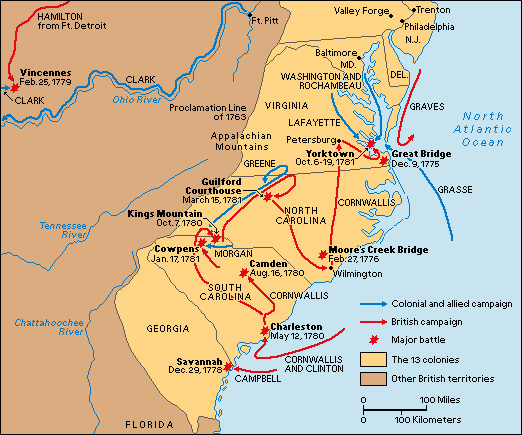

On March 15, 1781, British troops under Cornwallis defeated an American force at the Battle of Guilford Courthouse, in North Carolina. Later that spring, Cornwallis moved his troops to Virginia to stop the flow of supplies to American forces operating further to the south. However, Cornwallis departed from the British strategy by failing to gain control of North and South Carolina before advancing northward.

General Sir Henry Clinton, commander in chief of the British Army, became concerned that Cornwallis’s campaign would fail. Clinton also feared an American attack on the British base at New York City. Clinton therefore ordered Cornwallis to adopt a defensive position along the Virginia coast and to prepare to send his troops to New York. Cornwallis moved to Yorktown, along Chesapeake Bay.

At the same time, General Washington prepared an operation to drive the British from New York City. In July 1780, Lieutenant General Jean Baptiste Donatien de Vimeur, Comte de Rochambeau, and about 5,500 French soldiers had reached America. They cooperated with Washington’s troops outside British-held New York. Plans changed in August 1781, however, after Washington learned that a large French fleet under Admiral François Joseph, Comte de Grasse, was headed toward Virginia. De Grasse planned to block Chesapeake Bay and prevent Cornwallis from moving his troops by sea. Washington and Rochambeau therefore rushed their forces southward to trap Cornwallis on land.

In early September, a British naval force of 19 ships, led by Admiral Thomas Graves and Samuel Hood, sailed from New York City to battle de Grasse’s fleet. De Grasse’s force numbered 28 ships and would later be enlarged to 36. On September 5, the two naval forces fought at the mouth of Chesapeake Bay, but the battle had no clear winner. A week later, the British ships returned to New York City for repairs. Cornwallis’s troops remained at Yorktown.

Siege.

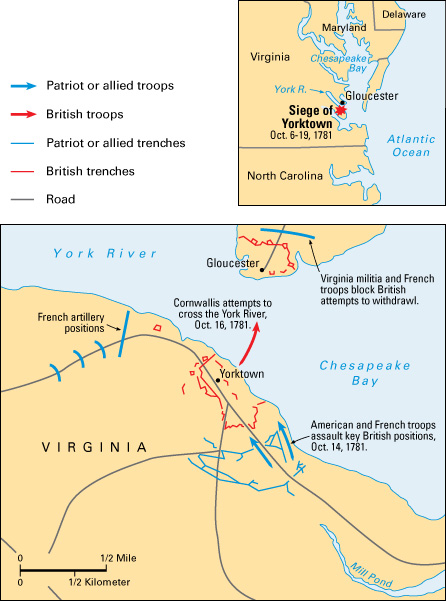

On Sept. 28, 1781, Washington and Rochambeau’s combined force of about 22,600 troops surrounded Cornwallis’s 9,700 men at Yorktown. Cornwallis also had some troops across the York River at Gloucester. However, these soldiers were blocked in by American and French forces.

On September 29, Cornwallis received a message from Clinton, informing him that the British were planning to send reinforcements from New York. Cornwallis decided to fall back into Yorktown and wait for the promised reinforcements. That night, Cornwallis abandoned some of his trenches outside Yorktown and brought the troops inside the city. The next day, the American and French troops occupied Cornwallis’s abandoned trenches, shrinking the British lines.

Throughout the siege, the American and French troops fired cannons at Yorktown and dug trenches closer to the city. On the night of October 14, the American and French soldiers assaulted two key positions in front of Cornwallis’s left, which allowed them to move their artillery closer. Two nights later, Cornwallis attempted to ferry his soldiers across the York River to Gloucester. He hoped to unite with his troops there, overwhelm the smaller American and French force, and then join Clinton in New York. However, a storm drove the British troops back. British ammunition and supplies were running low, and no reinforcements were in sight. Cornwallis asked for terms of surrender on October 17.

Surrender.

On Oct. 19, 1781, the British surrendered more than 8,000 troops at Yorktown. These soldiers represented about a fourth of the British military force in America. Cornwallis claimed that he was ill, and he sent one of his officers to formally surrender. During the surrender, a British band played a tune called “The World Turned Upside Down.”

During the siege, about 150 British soldiers were killed, and about 325 were wounded. The American and French forces suffered about 80 soldiers killed and about 300 wounded. The French had about twice as many casualties as the Americans.

The siege of Yorktown did not end the war. Fighting dragged on in some areas for two more years. But the British defeat forced Britain’s prime minister to resign and brought a new group of British ministers to power early in 1782. They began peace talks with the Americans. The Treaty of Paris, which ended the American Revolution, was signed on Sept. 3, 1783.