Holt, Harold (1908-1967), became prime minister of Australia in January 1966. His time in office was cut short, however, after he disappeared while swimming near Melbourne in December 1967. Holt was presumed to have drowned. He was the third Australian prime minister to die in office.

Holt was the leader of Australia’s Liberal Party, but he was not strongly identified with any particular set of political beliefs. Instead, he was known as a practical political leader who was less socially conservative than his predecessor, Sir Robert Gordon Menzies . Holt’s foreign policy was dominated by Australia’s involvement in the Vietnam War and his commitment to the military alliance with the United States. At the time, the Vietnam War (1957-1975) raged in Asia. Holt inherited and continued policies formed in the Cold War period of international tension and confrontation between the West, led by the United States, and the world’s Communist countries, led by the Soviet Union.

Early life and family

Harold Edward Holt was born on Aug. 5, 1908, in the Sydney suburb of Stanmore. Thomas and Olive Holt, his parents, were both schoolteachers. Harold attended three schools around Sydney and Canberra before he and his younger brother, Clifford (Cliff) Thomas, enrolled at Wesley College, a private school in Melbourne, in 1920. Harold graduated from the University of Melbourne with a law degree in 1930. He was admitted to the bar—that is, the body of lawyers licensed to practice law—in 1932 and established his own law practice in 1933. During this time, Holt developed a friendship with Robert Gordon Menzies, who would later become prime minister.

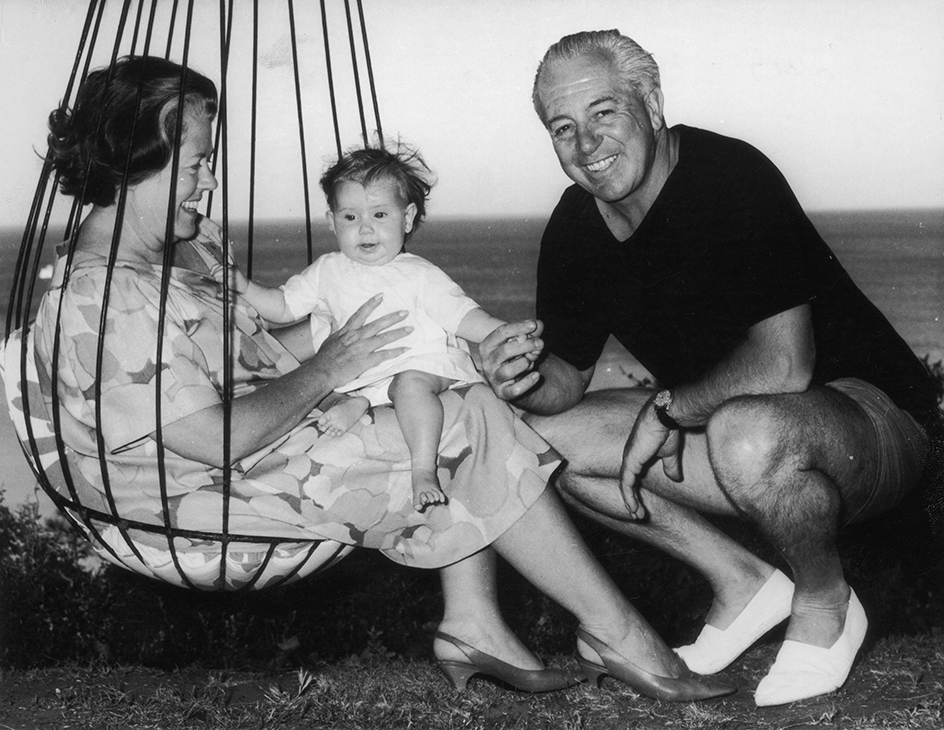

In the mid-1920’s, Holt met Zara Kate Dickens (1909-1989), a fashion boutique owner in Melbourne. The couple married in 1946 after Zara secured a divorce from her first husband, British Army officer James Fell. She brought three children into the marriage, Nicolas (born in 1935) and the twins Sam and Andrew (born in 1939). Holt legally adopted the children, and they later took his surname. The author of the biography The Life and Death of Harold Holt (2005), the Australian Anglican bishop Tom Frame, claimed in his book that Holt was the biological father of the twins. In 1968, Zara Holt was named a dame commander of the Order of the British Empire for “devotion to the public interest.”

Political career

Harold Holt joined the United Australia Party (UAP), a center-right political party, in 1933. After twice failing to win a seat in Parliament in 1934, he won the House of Representatives seat of Fawkner, representing Melbourne suburbs, in a 1935 by-election (special election). In 1939, UAP leader Robert Gordon Menzies became prime minister. In the years that followed, Menzies became a major influence on Holt’s political career.

In April 1939, Menzies appointed Holt, at the age of 30, to a junior Cabinet position. Holt assisted the minister for supply and development and, later, other Cabinet ministers until the spring of 1940. In May 1940, during World War II (1939-1945), Holt enlisted in the Australian Army and served as a gunner. He remained in the Army for less than five months before receiving a discharge because Prime Minister Menzies recalled him to government service.

Following the election of September 1940, Menzies appointed Holt to be minister of labour and national service, a newly created position for supervising the use of men and women during World War II. However, the Menzies government was voted out of office in August 1941. Holt then became a member of the opposition while resuming his law practice.

The UAP was almost wiped out in the federal election of 1943. The next year, Menzies helped found the new Liberal Party and became its leader. Holt became a member of the Liberal Party and remained in Parliament representing Fawkner. After Labor reforms expanded the House of Representatives, Holt became a candidate for the seat of Higgins, a new seat created from the Fawkner district. Holt won the seat and held it until his death.

In the 1949 federal election, the Liberal Party joined with the Country Party to defeat the Labor government, and Menzies again became prime minister. Menzies appointed Holt to the Cabinet positions of minister for immigration, which he held until 1956, and minister for labour and national service, which he held until 1958.

In 1956, Holt became deputy leader of the Liberal Party. In 1958, following another federal election, Holt was appointed treasury minister. In 1966, Menzies retired, and Holt succeeded him as Liberal Party leader. On Jan. 26, 1966, he became prime minister.

Prime minister

As prime minister, Holt’s political style differed from that of Menzies. Holt was more informal and less aggressive in manner. He enjoyed wearing the latest in clothing fashions and was a strong believer in physical fitness. As a result, he appeared to the public to be significantly younger than his age of 57.

Government policy.

In one of his first actions as prime minister in 1966, Holt expanded Australia’s troop commitment in the Vietnam War. The action caused opposition to the war to increase in Australia. Holt also sought to show support for the United States. He had met U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1942, when Johnson, then serving as a naval officer during World War II, visited Australia with General Douglas MacArthur. In October 1966, Johnson became the first U.S. president to make an official visit to Australia.

The Holt government made major changes in Australia’s immigration policy. Previously, the country had followed what was known as the “White Australia” policy, which limited the entry of non-European immigrants into Australia. The Migration Act of 1966 allowed immigrants from non-European countries easier access to Australia. The act was especially significant for Vietnamese refugees who were fleeing the violence of the Vietnam War. In 1967, Australians voted to remove a clause in the Constitution that did not allow Australia’s Indigenous peoples—the Aboriginal peoples and Torres Strait Islander peoples—to be counted in the national census. The Constitution was also changed to allow the Federal Parliament to pass laws affecting Indigenous peoples.

Holt made vigorous efforts to improve Australia’s relations with Asian countries. In 1966, he traveled throughout Southeast Asia, meeting with Asian political leaders. In 1967, Holt expanded his foreign travels to include meetings with political leaders in such countries as South Korea, Cambodia, and Laos.

Criticism and controversy.

Holt’s government was involved in several controversies. In 1964, the destroyer Voyager collided with the aircraft carrier Melbourne off Jervis Bay. The Voyager lost 82 sailors in the collision, the highest peacetime death toll of military personnel in Australian naval history. Although the collision occurred before Holt took office, his government received severe criticism for its handling of the official investigation that followed.

Holt also faced criticism for the “VIP flights affair,” in which his government failed to give Parliament the names of high-ranking passengers who had flown on government airplanes. In addition, the opposition attacked Holt’s government over the rising cost of developing a new bomber for the Royal Australian Air Force. Meanwhile, protests against Australia’s participation in the Vietnam War increased in intensity.

Death.

A week before a planned Christmas holiday in 1967, Holt traveled to Melbourne for a weekend. On the afternoon of December 17, he went swimming alone off Cheviot Beach at the resort town of Portsea, near Melbourne. Holt disappeared in the choppy waters, and his body was never recovered. Two days after his disappearance, Holt was presumed dead. On December 19, Deputy Prime Minister John McEwen was sworn in as the new prime minister.

Several rumors about Holt’s death quickly gained circulation, including a suggestion that he committed suicide. However, after an extensive investigation, officials ruled his death accidental.

On December 22, a memorial service was held at St. Paul’s Anglican Cathedral in Melbourne. Many world leaders attended the service, including U.S. President Johnson and British Prime Minister Harold Wilson.