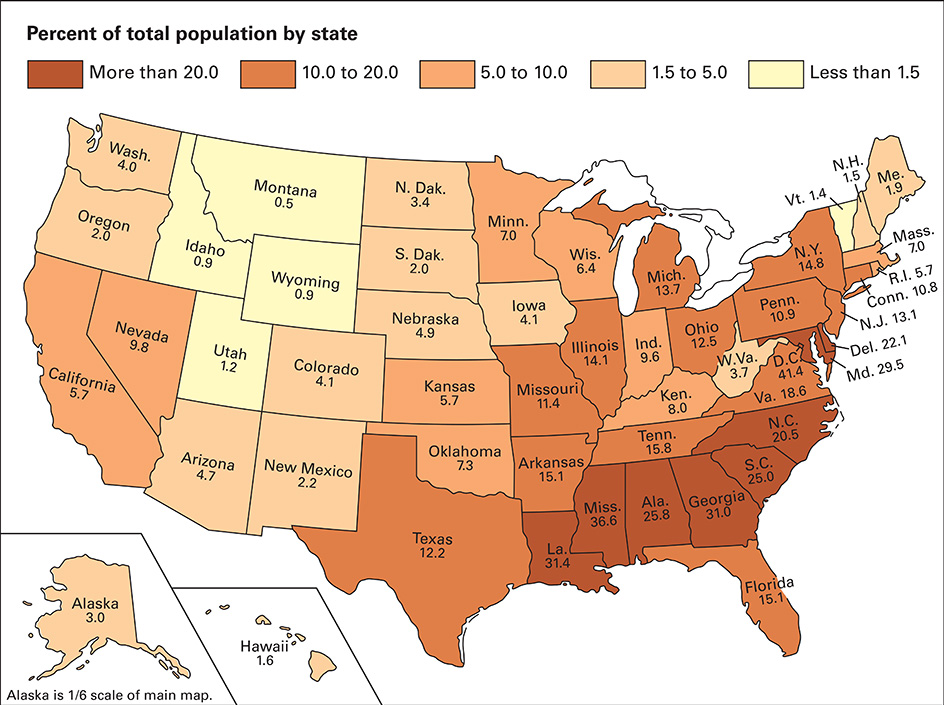

African Americans are Americans mostly or partly of African descent. About 40 million African Americans live in the United States. They account for 13 percent of the nation’s total population and, in number, trail only Hispanic Americans among minority groups. About half of all Black Americans live in the Southern States. Most of the rest live in large cities in other regions.

African Americans have used a number of terms to refer to themselves. The terms Negro (which means black in Spanish and Portuguese) and colored were commonly used until the mid-1960’s. These terms referred to the dark brown skin color of many African Americans. Since then, most African Americans have chosen to express deep pride in their color or origin by using other terms. At various times they have called themselves blacks, Afro-Americans, black Americans, or African Americans. Discussion of preferred names in African American communities continues today. For example, Black activists and scholars have argued for capitalization of the term Black and use of the term Black Americans (with an upper-case B) to recognize the shared culture, experiences, and identity of a people who have endured a centuries-long struggle for equality, recognition, and respect.

The majority of African Americans trace their origin to an area in western Africa that was controlled by three great and wealthy Black empires from about the A.D. 300’s to the late 1500’s. These empires—Ghana, Mali, and Songhai—thrived on trade and developed efficient governments. During the early 1500’s, European nations began a slave trade in which people kidnapped from western Africa were brought to European colonies in the Americas. For about the next 300 years, millions of enslaved Black Africans were shipped across the Atlantic Ocean to North and South America. About 500,000 of the Africans were brought to what is now the United States.

The history of African Americans is largely the story of their struggle for freedom and equality. From the 1600’s until the American Civil War (1861-1865), most Black Americans worked as slaves throughout the South. They did much to help Southern agriculture expand. At the same time, free Black Americans helped develop industry in the North. Even after 1865, when slavery was finally abolished in the United States, Black Americans briefly gained their civil rights during a period called Reconstruction. But after Reconstruction, they again lost those rights and suffered from widespread segregation (separation by race) and poverty. The determined efforts of African Americans to achieve equality and justice led to the start of a strong civil rights movement in the United States in the 1950’s.

The lives of African Americans have improved since the 1950’s. More Black Americans are making important contributions in all areas of American life. The election in 2008 of Barack Obama as the first African American president reflects the significant strides toward equality that have been made in the United States. However, many African Americans still suffer from segregation and poverty, discrimination in jobs and housing, and other problems.

This article describes the African background of Black Americans and traces their history since their arrival in North America.

The African background

The cultural heritage.

The ancestors of most Black Americans came from an area of Africa known as the Western Sudan. This area was about as large as the United States, not including Hawaii and Alaska. It extended from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to Lake Chad in the east and from the Sahara in the north to the Gulf of Guinea in the south.

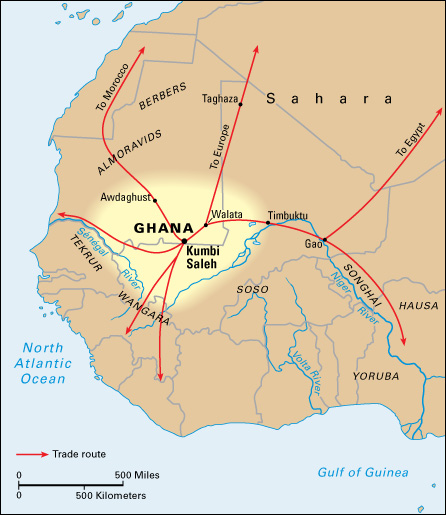

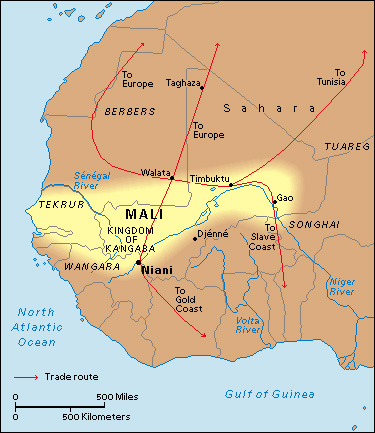

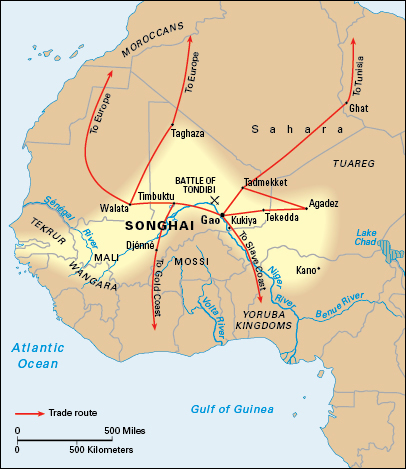

From about the A.D. 300’s to 1591, three highly developed Black African empires, in turn, controlled all or most of the Western Sudan. They were Ghana, Mali, and Songhai. Their economies were based on farming, on mining gold, and on trade with Arabs of northern Africa.

Ghana ruled much of the Western Sudan from the 300’s to the mid-1000’s. The Ghanaians became the first people in western Africa to smelt iron ore. They made arrows, swords, and other weapons of iron, which helped them conquer nearby nations.

In 1235, the Malinke people of Mali began to develop the second great Black African empire of the Western Sudan. By 1240, they controlled all Ghana. The Mali Empire’s most famous ruler was Mansa Musa, who reigned from 1312 to about 1337. Mansa Musa encouraged the practice of Islam, the religion of the Muslims. Under his rule, Mali reached its height of wealth, political power, and cultural achievement.

Beginning in the 1400’s, the Songhai Empire gained control of most of northwestern Africa south of the Sahara, including much of Mali. Under Askia Muhammad, who ruled Songhai from 1493 to 1528, the empire had a well-organized central government and excellent universities in such cities as Timbuktu and Djénné. Like Mansa Musa, Askia encouraged his people to practice the Islamic faith. Invaders from Morocco conquered Songhai in 1591.

Some ancestors of African Americans lived in smaller nations in the Western Sudan. These nations included Oyo, Benin, Dahomey, and Ashanti. Their economies also depended on farming, trade, and gold mining. For more details on the major Black African empires, see Ghana Empire ; Mali Empire ; Songhai Empire.

Beginning of the slave trade.

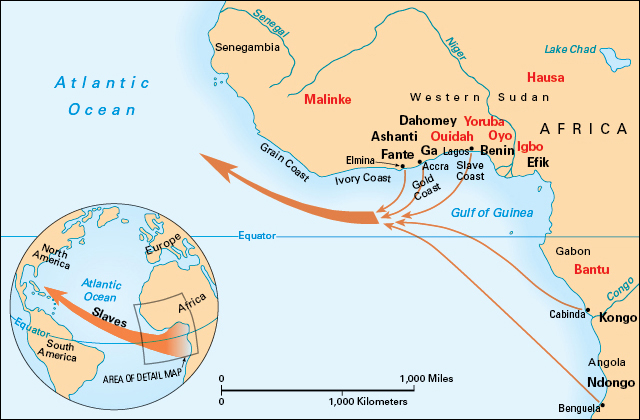

Africans had practiced slavery since ancient times. In most cases, people captured in warfare were sold to Arab traders of northern Africa. Portugal and Spain became increasingly involved in the African slave trade during the early 1500’s, after they had established colonies in the Americas. Portugal acquired African slaves to work on sugar plantations that its colonists developed in Brazil. Spain used slaves on its sugar plantations in the Caribbean. During the early 1600’s, the Netherlands, France, and England also began to use enslaved Africans in their American colonies.

The Europeans obtained enslaved people from Africans who continued to sell their war captives or trade them for rum, cloth, and other items, especially guns. The Africans wanted the guns for use in their constant warfare with neighboring peoples.

The slave trade took several triangular routes. Over one route, ships from Europe transported manufactured goods to the west coast of Africa. There, traders exchanged the goods for enslaved persons. Next, the captives were carried across the Atlantic Ocean to the Caribbean and sold for huge profits. This part of the route was called the Middle Passage because it was the middle leg of the journey from Africa to the New World. The traders used much of their earnings to buy sugar, coffee, and tobacco in the Caribbean. The ships then took these products to Europe.

On another triangular route, ships from the New England Colonies carried rum and other products to Africa, where they were exchanged for enslaved people. The ships then transported these people to the Caribbean to be sold. The slave traders used some of their profits to buy sugar and molasses, which they took back to New England and sold to rum producers.

The slave trade was conducted for profit. The captains of slave ships therefore tried to deliver as many healthy captives for as little cost as possible. Some captains used a system called loose packing to deliver slaves. Under that system, captains transported fewer enslaved people than their ships could carry in the hope of reducing sickness and death among them. Other captains preferred tight packing. They believed that many of their captives would die on the voyages anyway and so carried as many slaves as their ships could hold.

Most slave ship voyages across the Atlantic took several months. The enslaved people were chained below deck all day and all night except for brief periods of exercise. Their crowded conditions led to the chief horrors of the Middle Passage—filth, stench, disease, and death.

The Atlantic slave trade operated from the 1500’s to the mid-1800’s. Between 10 million and 12 million Africans were enslaved during this period. Of this total, what is now the United States received about 5 percent.

The years of slavery

Some scholars believe that the first Black Africans in America came with the expeditions led by Christopher Columbus, starting in 1492. Enslaved Black people traveled to North and South America with French, Portuguese, and Spanish explorers throughout the 1500’s.

The best-known Black African to take part in the early explorations of North America was an enslaved man named Estevanico. In 1539, he crossed what are now Arizona and New Mexico on an expedition sent by Antonio de Mendoza, ruler of Spain’s colony in America.

Colonial times.

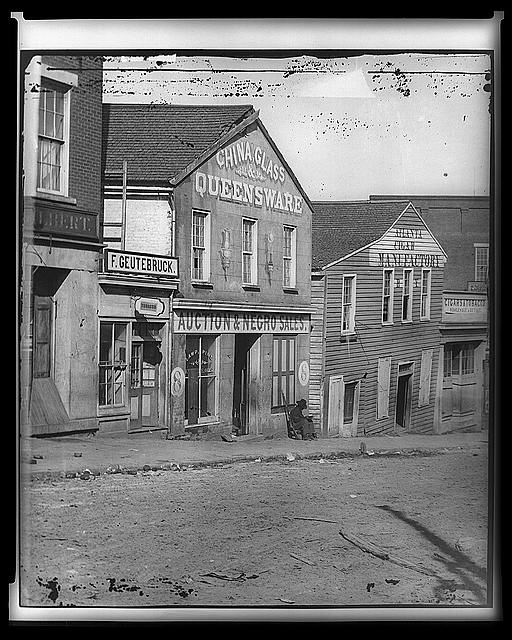

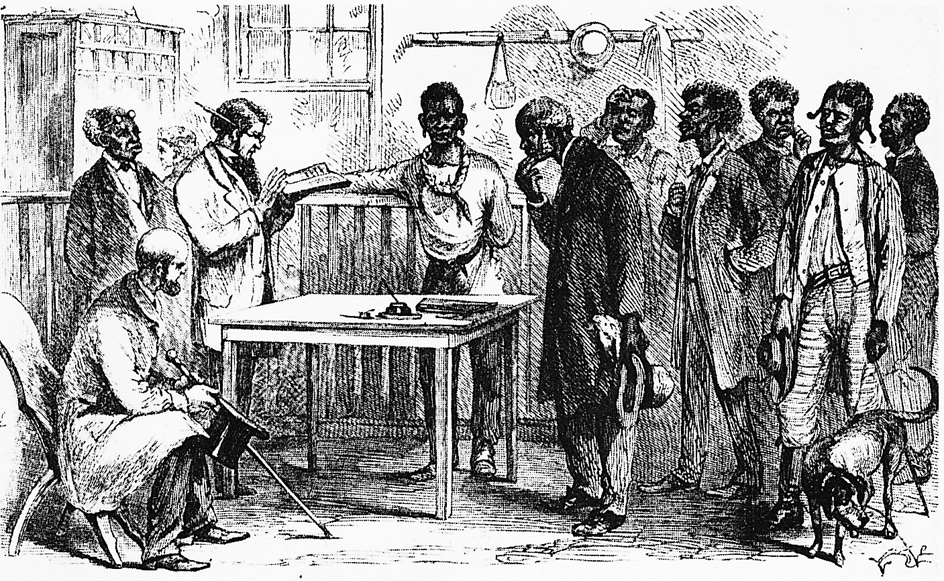

The first Black Africans in the American Colonies were brought in, like many lower-class white people, as indentured servants. Most indentured servants had a contract to work without wages for a master for four to seven years, after which they became free. Black people brought in as slaves, however, had no right to eventual freedom. The first Black indentured servants arrived in Jamestown in the colony of Virginia in 1619. They had been captured in Africa and were sold at auction in Jamestown. After completing their service, some Black indentured servants bought property. But racial prejudice among white colonists forced most free Black people to remain in the lowest level of colonial society.

The first enslaved Black Africans in the American Colonies also arrived during the early 1600’s. The enslaved population increased rapidly during the 1700’s as newly established colonies in the South created a great demand for plantation workers.

By 1750, about 200,000 enslaved people lived in the colonies. The majority lived in the South, where the warm climate and fertile soil encouraged the development of plantations that grew rice, tobacco, sugar cane, and later cotton. Most plantation slaves worked in the fields. Others were craftworkers, messengers, and servants.

Only 12 percent of slaveowners operated plantations that had 20 or more slaves. But more than half of all the country’s enslaved persons worked on these plantations. Most of the other slaveowners had small farms and only a few slaves each. Under arrangements with their masters, some enslaved people could hire themselves out to work for other white people on farms or in city jobs. Such arrangements brought income to both the slaves and the masters.

The cooler climate and rocky soil of the Northern and Middle colonies made it hard for most farmers there to earn large profits. Many enslaved people in those colonies worked as skilled and unskilled laborers in factories, homes, and shipyards and on fishing and trading ships.

During the mid-1600’s, the colonies began to pass laws called slave codes. In general, these codes prohibited enslaved people from owning weapons, receiving an education, meeting one another or moving about without the permission of their masters, and testifying against white people in court. Enslaved people received harsher punishments for some crimes than white people. A master usually received less punishment for killing a slave than for killing a free person for the same reason. Enslaved people on small farms probably had more freedom than plantation slaves, and slaves in urban areas had fewer restrictions in many cases than slaves in rural areas.

By 1770, there may have been 40,000 or more free Black people in the American Colonies. They included runaway slaves, descendants of early indentured servants, and Black immigrants from the Caribbean. Many free Black people opposed British rule. One of the best-known African American patriots was Crispus Attucks, who died in the Boston Massacre of 1770 while mocking the presence of British soldiers.

During the American Revolution (1775-1783), however, most Black people probably favored the British. They believed that a British victory would offer them their earliest or best chance for freedom. But about 5,000 people of Black African descent fought on the side of the colonists. Most of them were freedmen or slaves from the Northern and Middle colonies. Black heroes of the war included Peter Salem and Salem Poor of Massachusetts, who distinguished themselves in the Battle of Bunker Hill in 1775.

The growth of slavery.

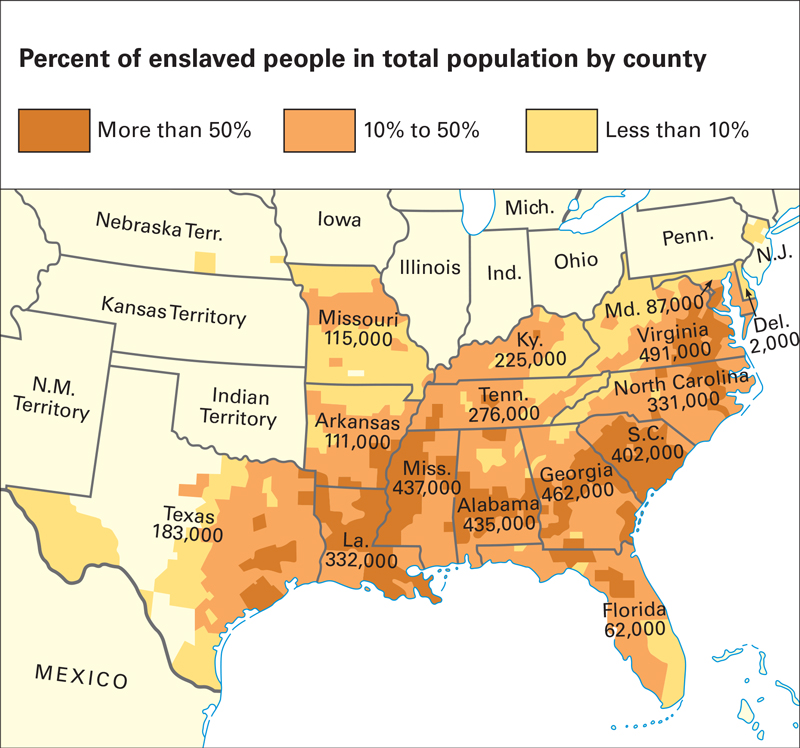

By the early 1800’s, more than 700,000 slaves lived in the South. They accounted for about a third of the region’s people. Enslaved people outnumbered white people in South Carolina and made up over half the population in both Maryland and Virginia.

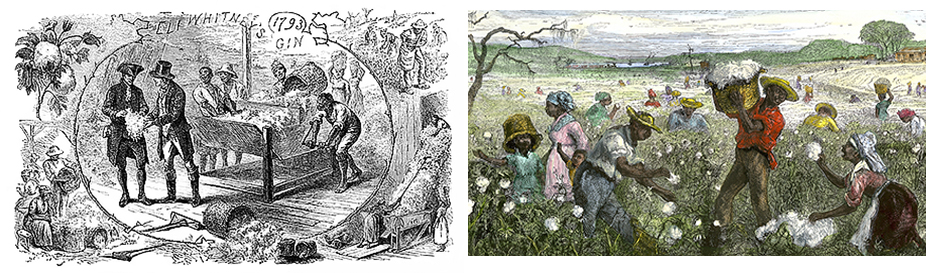

Slavery began to develop even deeper roots in the South after Eli Whitney of Massachusetts invented his cotton gin in 1793. This machine removed the seeds from cotton as fast as 50 people working by hand. It probably contributed more to the growth of slavery than any other development. Whitney’s gin enabled farmers to meet the rapidly rising demand for cotton. As a result, the Southern cotton industry expanded, and cotton became the chief crop in the region. The planters needed more and more workers to pick and bale the cotton, which led to large increases in the enslaved population. The thriving sugar cane plantations of Louisiana also used many enslaved people during the first half of the 1800’s. By 1860, about 4 million slaves lived in the South.

Numerous enslaved people protested against their condition. They used such day-to-day forms of rebellion as destroying property, running away, pretending illness, and disobeying orders. Major slave protests included armed revolts and mutinies. The most famous of about 200 such revolts was led by Nat Turner, an enslaved preacher. The revolt broke out in 1831 in Southampton County in Virginia. The rebels killed about 60 white people before being captured. The best-known slave mutiny occurred in 1839 aboard La Amistad, off the coast of Cuba. A group of Africans, led by Joseph Cinque, brought the vessel to Long Island in New York. The slaves were given their freedom soon afterward.

Enslaved people received beatings or other physical punishment for refusing to work, attempting to run away, or participating in plots or rebellions against their owners. Some were executed for rebelling.

Free Black people.

The American Revolution helped lead to new attitudes about slavery, especially among white people in the North. The war inspired a spirit of liberty and an appreciation for the service of the Black soldiers. Partly for this reason, some Northern legislatures adopted laws during the late 1700’s that provided for the immediate or gradual end of slavery. Another reason for such laws was simply that enslaved people had no essential role in the main economic activities of the North.

The census of 1790 revealed that the nation had about 59,000 free Black people, including about 27,000 in the North. By the early 1800’s, most Northern states had taken steps to end slavery. Besides former slaves freed by law, free Black people included those who had been freed by their masters, who had bought their freedom, or who had been born of free parents.

After the American Revolution, numerous free Black people found jobs in tobacco plants, textile mills, and other factories. Some worked in shipyards, on ships, and later in railroad construction. Many became skilled in carpentry and other trades. Some became merchants and editors. The best-known editors were Samuel Cornish and John Russwurm, who helped start the first Black newspaper, Freedom’s Journal, in 1827.

Most white Americans treated free Black Americans as inferiors. Many hotels, restaurants, theaters, and other public places barred them. Few states gave free Black people the right to vote. Their children had to attend separate schools. Some colleges and universities, such as Bowdoin in Maine, and Oberlin in Ohio, admitted Black students. But the limited number of admissions led to the opening of Black colleges, including Lincoln University in Pennsylvania in 1854 and Wilberforce University in Ohio in 1856.

In both the North and the South, churches either banned Black people or required them to sit apart from white people. As a result, some Black Americans set up their own churches. In 1816, Richard Allen, a Black Philadelphia minister, helped set up the African Methodist Episcopal Church, the first Black denomination in the country.

The rising number of free Black people alarmed many white people and led to further restrictions on their activities. In parts of New England, free Black Americans could not visit any town without a pass. They also needed permission to entertain enslaved people in their homes. In the South, free Black people could be enslaved if caught without proof that they were free. Fears that free Black people would lead slave revolts encouraged almost all states to pass laws severely limiting the right of free Black Americans to own weapons.

Increasing concern over the large number of free Black people led to the founding of the American Colonization Society in 1816. The society was sponsored by well-known supporters of slavery, including U.S. Representatives John C. Calhoun of South Carolina and Henry Clay of Kentucky. Their plan was to lessen “the race problem” by transporting free Black Americans on a voluntary basis to Africa. In 1822, the society established the Black American colony of Liberia on the continent’s west coast. In 1847, Liberia became the first self-governing Black republic in Africa. However, most free Black people felt that the United States was their home. As a result, only about 12,000 of them had volunteered to settle in Liberia by 1850.

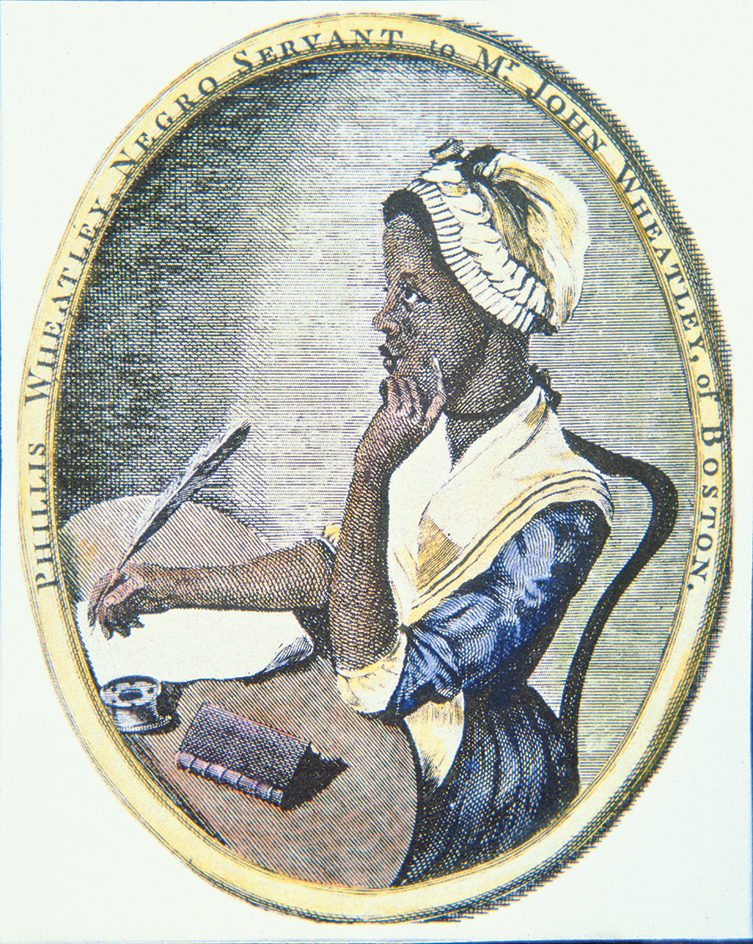

Despite their inferior position, a number of free Black people won widespread recognition during the late 1700’s and early 1800’s. For example, Phillis Wheatley gained fame for her poetry. Newport Gardner distinguished himself in music. Benjamin Banneker, a mathematician, published outstanding almanacs. Notable Black ministers included Absalom Jones in the North and George Liele and Andrew Bryan in the South. Paul Cuffe and James Forten gained great wealth in business. Tom Molineaux became known for his boxing skills.

By 1860, the nation had about 490,000 free Black people. But most of them faced such severe discrimination that they were little better off than those who remained enslaved.

The antislavery movement.

Many white Americans, particularly Northerners, felt that slavery was evil and violated the ideals of democracy. However, plantation owners and other supporters of slavery regarded it as natural to the Southern way of life. They also argued that Southern culture introduced the enslaved people to Christianity and helped them become “civilized.” Most white Southerners held such beliefs by 1860, though less than 5 percent of them owned slaves and only about half the slaveowners had more than five enslaved people. In addition, Southern farmers insisted that they could not make money growing cotton without cheap slave labor.

The Southern States hoped to expand slavery as new states were admitted to the Union. However, the Northern States feared they would lose power in Congress permanently if more states that permitted slavery were admitted. The North and the South thereby became increasingly divided over the spread of slavery.

The slavery issue created heated debate in Congress after the Territory of Missouri applied for statehood in 1818. At the time, there were 11 slave states, in which slavery was allowed, and 11 free states, in which it was prohibited. Most Missourians supported slavery, but many Northern members of Congress did not want Missouri to become a slave state. In 1820, Congress reached a settlement known as the Missouri Compromise. This measure admitted Missouri as a slave state, but it also called for Maine to enter the Union as a free state. Congress thus preserved the balance between free and slave states at 12 each.

New, aggressive opponents of slavery began to spring up in the North during the 1830’s. Their leaders included William Lloyd Garrison, Lucretia Mott, Lewis Tappan, and Theodore Dwight Weld. During the 1830’s and 1840’s, these white abolitionists were joined by many free Black people, including such former slaves as Frederick Douglass, Henry Highland Garnet, Harriet Tubman, and Sojourner Truth.

Most of the abolitionist leaders attacked slavery in writings and public speeches. Garrison began to publish an antislavery newspaper, The Liberator, in 1831. Douglass, the most influential Black American leader of the time, started an abolitionist newspaper called the North Star in 1847. Tubman and many other abolitionists helped people enslaved in Southern states escape to the free states and Canada. Tubman returned to the South 19 times and personally led about 300 enslaved people to freedom. She and others used a network of routes and housing to assist the escapees. This network became known as the underground railroad.

The deepening division over slavery.

After 1848, Congress had to deal with the question of whether to permit slavery in the territories that the United States gained from Mexico as a result of the Mexican War (1846-1848). The territories covered what are now California, Nevada, Utah, and parts of four other states. Following angry debates among the members of Congress, Senators Henry Clay of Kentucky and Daniel Webster of Massachusetts helped work out a series of measures that became known as the Compromise of 1850. The Compromise allowed slavery to continue but prohibited the slave trade in Washington, D.C. A key measure in the Compromise admitted California to the Union as a free state. Another agreement gave the residents in the other newly acquired areas the right to decide for themselves whether to allow slavery. The Compromise included a federal fugitive slave law that was designed to help slaveowners get back runaway slaves.

The Compromise of 1850 briefly ended the heated arguments in Congress over the slavery issue. However, the abolitionist movement and the hostility between the North and the South continued. The publication of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s antislavery novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1851-1852) greatly increased the tensions between Northerners and Southerners. In addition, attempts by Northerners to stop enforcement of the fugitive slave law further angered Southerners.

The quarrel over slavery flared again in Congress in 1854, when it passed the Kansas-Nebraska Act. This law created two federal territories, Kansas and Nebraska, and provided that the people of each territory could decide whether to permit slavery. Most Nebraskans opposed slavery. However, bitter, bloody conflicts broke out between supporters and opponents of slavery in Kansas. In 1856, for example, the militant abolitionist John Brown led a raid against supporters of slavery in a small settlement on Pottawatomie Creek in Kansas. Brown’s group killed five men and focused the nation’s attention on the conflict in the territory, which became known as “Bleeding Kansas.” In the end, Kansas joined the Union as a free state in 1861.

Supporters of slavery won a major victory in 1857, when the Supreme Court of the United States issued its ruling in the case of Dred Scott v. Sandford. In the Dred Scott Decision, the court denied the claim of Scott, a slave, that his residence in a free state and later a free territory for a time made him free. The court also declared that no Black person—free or slave—could be a U.S. citizen. In addition, it stated that Congress had no power to ban the spread of slavery.

Tension in the South increased again in 1859, when John Brown led another abolitionist group in seizing the United States arsenal at Harpers Ferry in Virginia (now West Virginia). Federal troops quickly captured Brown, and he was executed later that year. But his raid helped convince many Southerners that the slavery issue would lead to fighting between the North and the South.

The end of slavery

Slavery became a major issue in the U.S. presidential election of 1860. Many Democrats in the North opposed the spread of slavery, but Democrats in the South favored it. Each group nominated its own candidate for president, thereby splitting their party. Most Republicans opposed the expansion of slavery. They chose Abraham Lincoln of Illinois as their presidential candidate. In November 1860, he was elected president.

Loading the player...Abraham Lincoln

The American Civil War.

Southerners feared that Lincoln would limit or end slavery. On Dec. 20, 1860, South Carolina seceded (withdrew) from the Union. Early in 1861, six other Southern states seceded. The seceded states took the name Confederate States of America. On April 12, 1861, Confederate troops attacked Fort Sumter, a United States military base in South Carolina, and the American Civil War began. Four more slave states joined the Confederacy soon afterward. Four other slave states—Missouri, Kentucky, Maryland, and Delaware—remained loyal to the Union.

At the start of the Civil War, Lincoln’s chief concern was to preserve the Union, not to end slavery. He therefore refused requests of African Americans to join the Union Army. He felt that their participation in the war could lead more slave states to secede. Lincoln also knew that many Northerners were hostile toward Black people and so might oppose the use of Black troops.

A number of developments gradually persuaded Lincoln to make the war a fight against slavery. For example, some Union military commanders, without the president’s consent, had freed enslaved people in areas they had conquered. Furthermore, abolitionists and Black leaders urged that the war be fought to end slavery, and they demanded the use of Black troops. Most importantly, the war was going badly for the Union. By fighting against slavery, Lincoln hoped to strengthen the war effort in the North and weaken it in the South.

In March 1862, Lincoln gave Congress a plan for the gradual freedom of enslaved people. The plan included payment for the slaveowners. In April, Lincoln approved legislation that ended slavery in the District of Columbia and provided funds for any freed slaves who wished to move to Haiti or Liberia. In June, Lincoln signed a bill that ended slavery in all federal territories.

By July 1862, Lincoln was ready to accept African Americans in the Union Army. In September, he issued a preliminary order to emancipate (free) the slaves. It declared that all enslaved people in areas or states in rebellion against the United States on Jan. 1, 1863, would be forever free. The order excluded areas still loyal to the Union, meaning that they might retain slaves. The order had no immediate effect in the Southern-controlled areas, but it meant that each Union victory brought the end of slavery closer. The final order was issued on Jan. 1, 1863, as the Emancipation Proclamation. African Americans referred to that day as the Day of Jubilee. Bells rang from the spires of most Northern Black churches to celebrate the day.

Over 200,000 African Americans fought on the side of the Union. They were discriminated against in pay, assignments, and rank. Nevertheless, many of them contributed greatly to the war effort. Robert Smalls of South Carolina, a harbor pilot, was one of the first Black heroes of the war. In 1862, he sailed a Confederate ship, the Planter, out of Charleston Harbor and turned it over to the Union. Smalls then joined the Union Navy. In 1863, Black regiments played an important role in the attack on Port Hudson, Louisiana. The fall of Port Hudson helped the Union gain control of the Mississippi River. Altogether, 23 Black soldiers won the Medal of Honor, the nation’s highest military award, for heroism during the Civil War.

About 40,000 Black troops—nearly all of them Union troops—died during the war. In April 1865, the main Southern army surrendered. In December 1865, the adoption of the 13th Amendment to the Constitution of the United States officially ended slavery throughout the nation.

The first years of freedom.

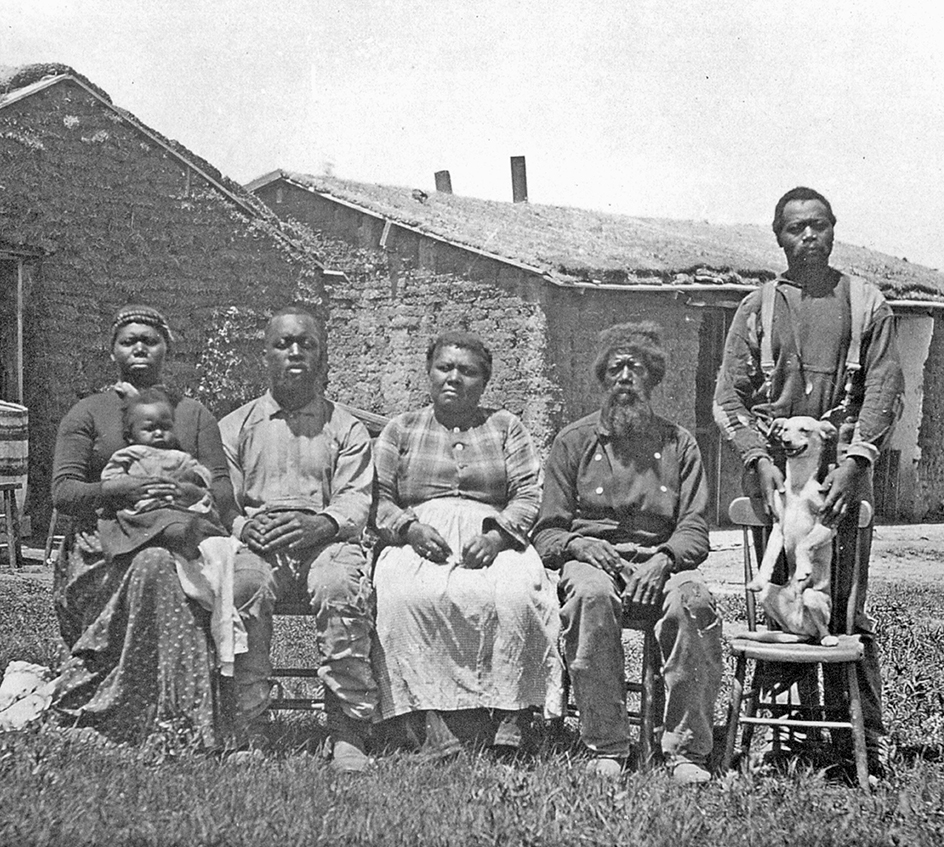

The period of rebuilding that followed the Civil War became known as Reconstruction. A major concern during Reconstruction was the condition of the approximately 4 million freedmen (freed slaves). Most of them had no homes, were desperately poor, and could not read and write.

To help the freedmen and homeless white people, Congress established the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands. The agency, better known as the Freedmen’s Bureau, operated from 1865 until 1872. It issued food and supplies to Black people; set up more than 100 hospitals; resettled more than 30,000 people; and founded over 4,300 schools. Some of the schools developed into outstanding Black institutions, such as Clark Atlanta University in Georgia, Fisk University in Nashville, Hampton University in Virginia, and Howard University in Washington, D.C.

In spite of its achievements, the Freedmen’s Bureau did not solve the serious economic problems of African Americans. Most of them continued to live in poverty. They also suffered from racist threats and violence and from laws restricting their civil rights. All these problems cast a deep shadow over their new freedom.

The legal restrictions on Black civil rights arose in 1865 and 1866, when many Southern state governments passed laws that became known as the black codes. These laws were like the earlier slave codes. Some black codes prohibited Black people from owning land. Others established a nightly curfew for Black people. Some permitted states to jail Black Americans for being jobless.

The black codes shocked a powerful group of Northern congressmen called Radical Republicans. These senators and representatives won congressional approval of the Civil Rights Act of 1866. The act gave African Americans the rights and privileges of full citizenship. The 14th Amendment to the Constitution, adopted in 1868, further guaranteed the citizenship of Black Americans. However, most Southern whites resented the new status of Black people. The white people simply could not accept the idea of former slaves voting and holding office. As a result, attempts by Southern Black citizens to vote, run for public office, or claim other civil rights were met by increasing violence from white people in the South. In 1865 and 1866, about 5,000 Southern Black Americans were murdered. Forty-six Black Americans were killed when their schools and churches were burned in Memphis in May 1866. In July, 34 Black Americans were killed during a race riot in New Orleans.

Some law enforcement officers encouraged or participated in assaults on Black people. But lawless groups carried out most attacks. One of the largest, the Ku Klux Klan, was organized in 1865 or 1866 in Pulaski, Tennessee. Bands of hooded Klansmen rode at night and beat and murdered many Black people and their white sympathizers. The Klan did much to deny Black Americans their civil and human rights throughout Reconstruction.

The federal government tried to maintain the rights of African Americans. In 1870 and 1871, Congress passed laws authorizing the use of federal troops to enforce the voting rights of Black people. These laws were known as the Enforcement Acts or the Ku Klux Klan Acts. In addition, President Ulysses S. Grant signed a proclamation demanding respect for the civil rights of all Americans.

Temporary gains.

The policies of the Radical Republicans enabled African Americans to participate widely in the nation’s political system for the first time. Congress provided for Black men to become voters in the South and called for constitutional conventions to be held in the defeated states. Many Black people attended the conventions held in 1867 and 1868. They helped rewrite Southern state constitutions and other basic laws to replace the black codes drawn up by whites in 1865 and 1866. In the legislatures elected under the new constitutions, however, Black lawmakers had a majority of seats only in the lower house in South Carolina. Most of the chief legislative and executive positions were held by Northern white Republicans who had moved to the South and by their white Southern allies. Angry white Southerners called the Northerners carpetbaggers to suggest that they could carry everything they owned when they came South in a carpetbag, or suitcase.

African Americans elected to important posts during Reconstruction included U.S. Senators Hiram R. Revels and Blanche K. Bruce of Mississippi and U.S. Representatives Joseph H. Rainey of South Carolina and Jefferson Long of Georgia. Others were Oscar J. Dunn, lieutenant governor of Louisiana; Richard Gleaves and Alonzo J. Ransier, lieutenant governors of South Carolina; P. B. S. Pinchback, acting governor of Louisiana; Francis L. Cardozo, secretary of state and state treasurer of South Carolina; and Jonathan Jasper Wright, an associate justice of the South Carolina Supreme Court. Most of them had college educations.

By the early 1870’s, Northern white people had lost interest in the Reconstruction policies of the Radical Republicans. They grew tired of hearing about the continual conflict between Southern Black and white people. Most Northern whites wanted to put Reconstruction behind them and turn to other things. Federal troops sent to the South to protect Black people were gradually withdrawn. Southern whites who had stayed away from elections to protest Black participation started voting again. White Democrats then began to regain control of the state governments from Black officials and their white Republican associates. In 1877, the last federal troops were withdrawn. By the end of that year, the Democrats held power in all the Southern state governments. For more details on the Reconstruction era, see Reconstruction.

The growth of discrimination

During the late 1800’s,

Black citizens in the South increasingly suffered from segregation, the loss of voting rights, and other forms of discrimination. Their condition reflected beliefs held by most white Southerners that white people were born superior to Black people with respect to intelligence, talents, and moral standards. In 1881, the Tennessee legislature passed a law that required railroad passengers to be separated by race. In 1890, Mississippi adopted several measures that in effect ended voting by African Americans. These measures included the passing of reading and writing tests and the payment of a poll tax before a person could vote.

Several decisions of the U.S. Supreme Court enabled the Southern States to establish “legal” segregation practices. In 1883, for example, the court declared the Civil Rights Act of 1875 to be unconstitutional. That act had guaranteed Black people the right to be admitted to any public place.

The Civil Rights Act of 1866 and the 14th Amendment to the Constitution, ratified in 1868, had forbidden the states to deny equal rights to any person. But in 1896, the Supreme Court ruled in the case of Plessy v. Ferguson that a Louisiana law requiring the separation of Black and white railroad passengers was constitutional. The court argued that segregation in itself did not represent inequality and that separate public facilities could be provided for the races as long as the facilities were equal. This ruling, known as the “separate but equal doctrine,” became the basis of Southern race relations. In practice, however, nearly all the separate schools, places of recreation, and other public facilities provided for Black people were far inferior to those provided for white people.

In spite of the increasing difficulties for African Americans, a number of them won distinction during the late 1800’s. For example, Samuel Lowery started a school for Black students in Huntsville, Alabama, in 1875 and won prizes at international fairs for silk made at the school. In 1883, Jan E. Matzeliger invented a revolutionary shoe-lasting machine that shaped the upper part of a shoe and fastened it to the sole. In 1887, Joe Clark and a group of other Black settlers founded Eatonville, Florida. It was the first African American settlement in the United States to be incorporated. Mary Church Terrell helped found the National Association of Colored Women in 1896 and advised government leaders on racial problems. Charles Waddell Chesnutt wrote The Conjure Woman, published in 1899. He became one of the first major African American novelists and short-story writers.

During the early 1900’s,

discrimination against Southern Black Americans became even more widespread. By 1907, every Southern state required racial segregation on trains and in churches, schools, hotels, restaurants, theaters, and other public places. The Southern States also adopted an election practice known as the white primary. The states banned Black people from voting in the Democratic Party’s primary elections by calling them “private affairs.” But the winners of the primary elections were certain of victory in the general elections because Republican and independent candidates got little support from white voters and rarely ran for office. By 1910, every Southern state had taken away or begun to take away the right of African Americans to vote.

The Ku Klux Klan used threats, beatings, and killings in its efforts to keep Black citizens from voting. More than 3,000 Black people had been lynched during the late 1800’s, and the Klan and similar groups lynched hundreds more throughout the South during the early 1900’s.

African Americans had little opportunity to better themselves economically. Some laws prohibited them from teaching and from entering certain other businesses and professions. Large numbers of Black workers had to take low-paying jobs as farm hands or servants for white employers. Many other poor Black people became sharecroppers or tenant farmers. They rented a small plot of land and paid the rent with money earned from the crops. They had to struggle to survive, and many ran up huge debts to their white landlords or the town merchants.

The rise of new Black leaders.

By the early 1900’s, the educator Booker T. Washington had become the most influential African American leader. Washington, who had formerly been enslaved, had been principal of Tuskegee Institute (now Tuskegee University) in Alabama since 1881. He urged Black people to stop demanding political power and social equality and to concentrate on economic advancement. Washington especially encouraged Black people to practice thrift and respect hard work. He asked white people to help Black people gain an education and make a decent living. Washington believed his program would lead to progress for African Americans and would keep peace between the races.

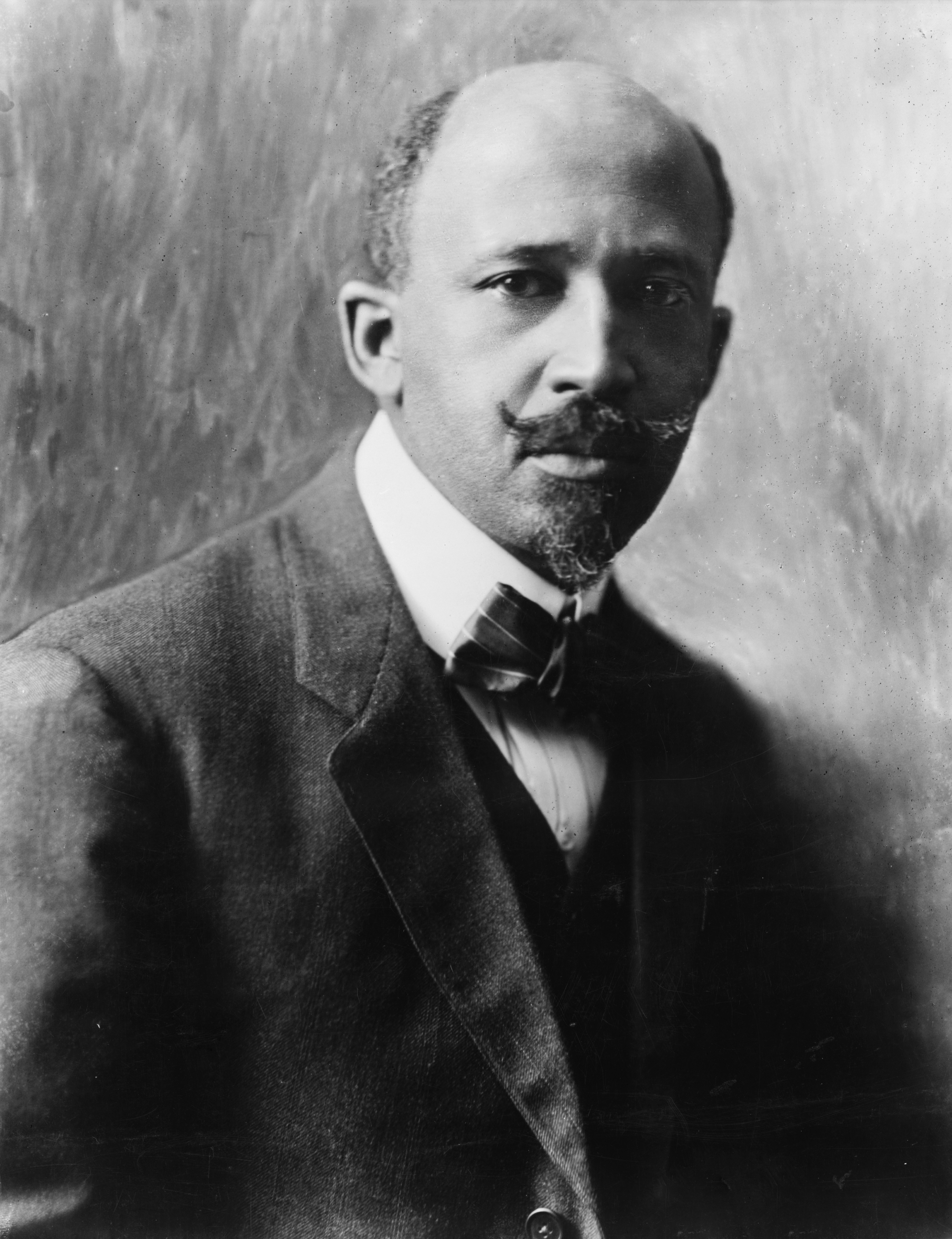

Many African Americans agreed with Washington’s ideas. But many others strongly rejected them. The chief opposition came from W. E. B. Du Bois, a sociologist and historian at Atlanta University. Du Bois’s reputation rested on such works as The Suppression of the African Slave-Trade to the United States of America, 1638-1870 (1896) and The Souls of Black Folk (1903).

Du Bois argued that Washington’s approach would not achieve economic security for African Americans. Instead, Du Bois felt Washington’s acceptance of segregation and the rest of his program would strengthen the beliefs that Black people were inferior and could be treated unequally. As evidence for their position, Du Bois and his supporters pointed to the continuing lynching of Black people and to the passage of additional segregation laws in the South. In 1905, Du Bois and other critics of Washington met in Niagara Falls, Canada, and organized a campaign to protest racial discrimination. Their campaign became known as the Niagara Movement.

Bitter hostility toward Black citizens erupted into several race riots during the early 1900’s. Major riots broke out in Brownsville, Texas, and Atlanta, Georgia, in 1906 and in Springfield, Illinois, in 1908. The riots alarmed many white Northerners as well as many Black people. In 1909, a number of white Northerners joined some of the African Americans in the Niagara Movement to form the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). The NAACP vowed to fight for racial equality. The organization relied mainly on legal action, education, protests, and voter participation to pursue its goals.

The Black migration to the North.

The efforts of new Black leaders and of the NAACP did little to end the discrimination, police brutality, and lynchings suffered by Black people in the South during the early 1900’s. In addition, Southern farmers had great crop losses because of floods and insect pests. All these problems persuaded many Black Southerners to move to the North. This movement is sometimes called the “Great Migration.”

During World War I (1914-1918), hundreds of thousands of Southern Black people migrated to the North to seek jobs in defense plants and other factories. The National Urban League, founded in New York City in 1910, helped the newcomers adjust to city life. About 400,000 African Americans served in the armed forces during World War I. They were put in all-Black military units.

From 1910 to 1930, about 1 million Black Southerners moved to the North. Most of them quickly discovered that the North did not offer solutions to their problems. They lacked the skills and education needed for the jobs they sought. Many of them had to become laborers or servants and thus do the same kinds of work they had done in the South. Others could find no work at all. Numerous Black Americans were forced to live crowded together in cheap, unsanitary, run-down housing. Large all-Black slums developed in big cities throughout the North. The segregated housing promoted segregated schooling. Poverty, crime, and despair plagued the Black communities, which became known as ghettos.

After World War I, race relations grew increasingly tense in the Northern cities. The hostility partly reflected the growing competition for jobs and housing between Black and white people. In addition, many African American veterans, after fighting for democracy, returned home with expectations of justice and equality. The mounting tension helped the Ku Klux Klan recruit thousands of members in the North. In the summer of 1918, 10 people were killed and 60 were injured in racial violence in Chester and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. A series of riots erupted in the summer of 1919. By the end of the year, 25 race riots had broken out across the country. At least 100 people died and many more were injured in the riots.

The Garvey movement

offered new hope for many African Americans deeply disturbed by the race riots of 1918 and 1919 and the economic and social injustice they encountered. The movement had begun when Marcus Garvey founded the Universal Negro Improvement Association in Jamaica in 1914. In 1917, Garvey brought the movement to Harlem, a Black community in New York City. By the mid-1920’s, he had established more than 700 branches of the association in 38 states.

Garvey tried to develop racial pride among America’s Black citizens. But he doubted that their life in the United States would ever be much improved. As a result, Garvey urged the establishment of a new homeland in Africa for dissatisfied Black Americans. His plans collapsed, however, when he was sent to prison in 1925 after having been convicted of using the mails to commit fraud.

The Harlem Renaissance and other achievements.

The Harlem Renaissance was an outpouring of African American literature chiefly in Harlem in the early 1900’s, particularly in the 1920’s. It demonstrated that some Black writers had acquired talents within American society which both white and Black people could appreciate. The writers drew their themes from the experiences of Black Americans in the Northern cities and the rural South. The best-known writers included James Weldon Johnson, Langston Hughes, Nella Larsen, Claude McKay, Countee Cullen, Jessie Redmon Fauset, and Jean Toomer.

African American musicians also gained fame among both white and Black audiences during the early 1900’s. A Black bandleader named W. C. Handy, who had composed “St. Louis Blues” in 1914, became known as the father of the blues. Jazz grew out of Black folk blues and ballads. The African American bandleaders Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington became the country’s leading jazz musicians.

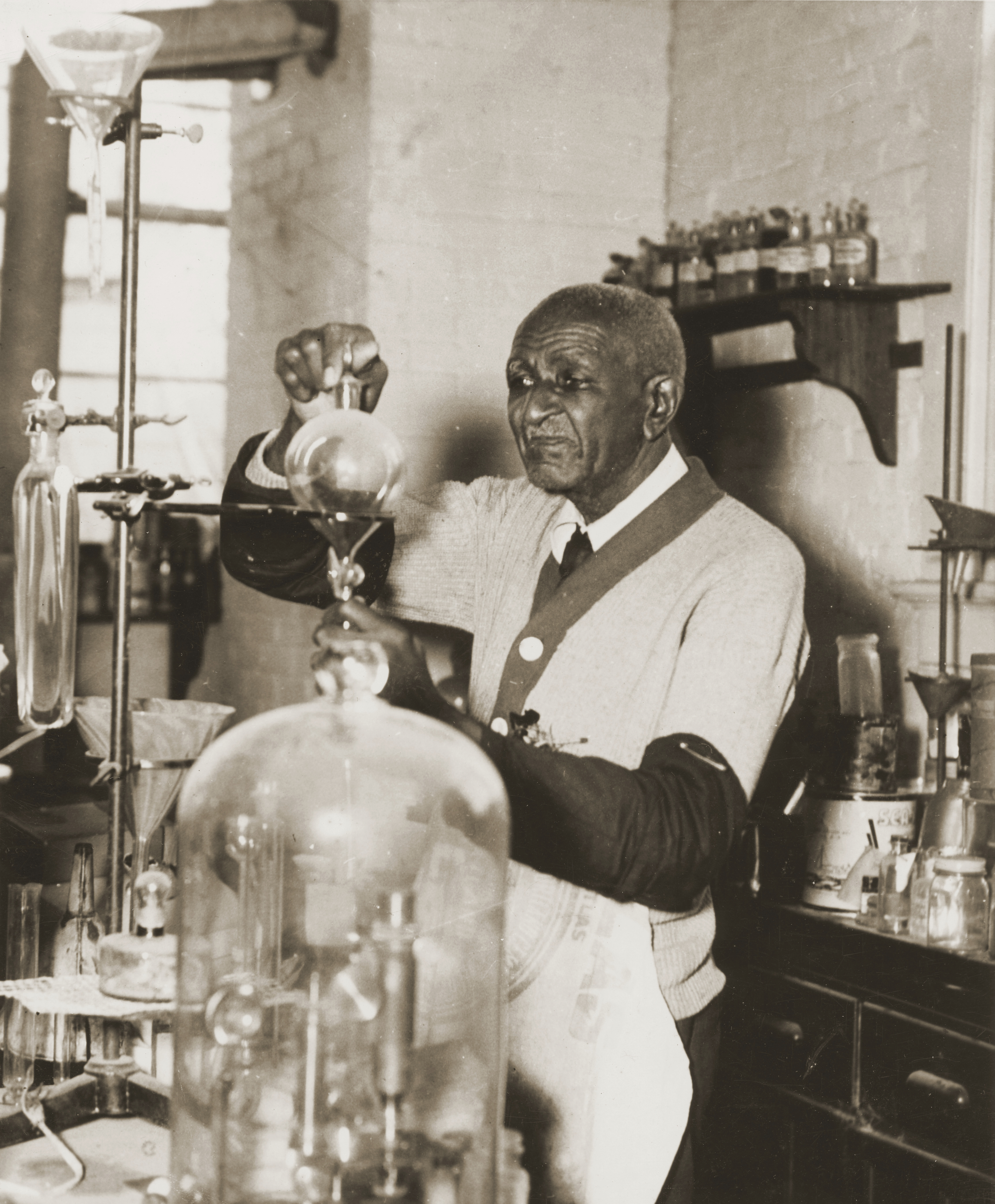

Another noted African American of the early 1900’s was the great agricultural researcher George Washington Carver. Carver created hundreds of products from peanuts, sweet potatoes, and other plants and revolutionized Southern agriculture. Other famous African Americans of the time included labor leader A. Philip Randolph; journalist Ida Wells-Barnett; singer, actor, and political activist Paul Robeson; actress Hattie McDaniel, the first African American to win an Academy Award; dancer Bill Robinson; U.S. Representative Oscar DePriest of Illinois; Olympic track and field gold medalist Jesse Owens; and heavyweight boxing champions Jack Johnson and Joe Louis.

The Great Depression

was a worldwide business slump in the 1930’s. The Depression brought hard times for most Americans, but especially for Black people, who became the chief victims of job discrimination. They adopted the slogan “Last Hired and First Fired” to express their situation.

To help ease the poverty in the ghettos, African Americans organized cooperative groups. These groups included the Colored Merchants Association in New York City and “Jobs for Negroes” organizations in St. Louis, Chicago, Cleveland, and New York City. The groups bought food and other goods in large volumes to get the lowest prices. They boycotted stores that had mostly Black customers but few, if any, Black workers.

Most African Americans felt that President Herbert Hoover, a Republican, had done little to try to end the Depression. In the elections of 1932, some Black voters deserted their traditional loyalty to the Republican Party. They no longer saw it as the party of Abraham Lincoln the emancipator but of Hoover and the Depression. In 1936, for the first time, most African Americans supported the Democratic Party candidate for president, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and helped him win reelection.

Roosevelt called his program the New Deal. It included measures of reform, relief, and recovery and benefited many Black Americans. A group of prominent Black citizens advised Roosevelt on the problems of African Americans. This group, called the Black Cabinet, included William H. Hastie and Mary McLeod Bethune. Hastie served as assistant solicitor in the Department of the Interior, as a U.S. district court judge in the Virgin Islands, and as a civilian aide to the secretary of war. Bethune, founder of what is now Bethune-Cookman University in Daytona Beach, Florida, directed the Black affairs division of a federal agency called the National Youth Administration. As a result of the New Deal, African Americans developed a strong loyalty to the Democratic Party.

African Americans deeply admired President Roosevelt’s wife, Eleanor, for her stand in an incident in 1939 involving the great concert singer Marian Anderson. The Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR), an organization of women directly descended from people who fought in the American Revolution, owned Constitution Hall in Washington, D.C. The DAR denied Anderson permission to perform at Constitution Hall because she was Black. Eleanor Roosevelt then resigned from the DAR and helped arrange for Anderson to sing, instead, at the Lincoln Memorial on Easter Sunday. Over 75,000 people—both Black and white—attended the concert.

During the early 1940’s, the NAACP stepped up its legal campaign against racial discrimination. The campaign achieved a number of important victories, including several favorable rulings by the U.S. Supreme Court. In 1941, for example, the court ruled that separate facilities for white and Black railroad passengers must be significantly equal. In 1944, the court declared that the white primary, which excluded Black citizens from voting in the only meaningful elections in the South, was unconstitutional.

Besides taking legal action, African Americans used new tactics to attack segregation in public places. In 1943, for example, the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) launched a sit-in at a Chicago restaurant. In this protest, Black demonstrators sat in places reserved for white people.

World War II (1939-1945)

opened up new economic opportunities for African Americans. Like World War I, it led to expanding defense-related industries and encouraged many rural Black Southerners to seek jobs in Northern industrial cities. During the 1940’s, about a million African American Southerners moved to the North. Discrimination again prevented many of them from getting work. In 1941, Black Americans led by A. Philip Randolph of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters threatened to march in Washington, D.C., to protest job discrimination. President Roosevelt then issued an executive order forbidding racial discrimination in defense industries.

Nearly 1 million African Americans served in the U.S. armed services during World War II, mostly in segregated units. In 1940, Benjamin O. Davis became the first Black brigadier general in the U.S. Army. His son, Benjamin O. Davis, Jr., later became the first Black lieutenant general in the Air Force. Desegregation of the armed forces began on a trial basis during the war. It became a permanent policy in 1948.

The civil rights movement

The beginning.

After World War II, three major factors encouraged the beginning of a new movement for civil rights. First, many African Americans had served with honor in the war. Black leaders pointed to the records of these veterans to show the injustice of racial discrimination against patriots. Second, African Americans in the urban North had made economic gains, increased their education, and registered to vote. Third, the NAACP had attracted many new members and received increased financial support from both white and Black people. It also included a new group of bright young lawyers.

Rulings by the U.S. Supreme Court during the 1940’s and 1950’s brought major victories for African Americans. In several decisions between 1948 and 1951, the court ruled that separate higher education facilities for Black students must be equal to those for white students. Largely because of federal court rulings, laws permitting racial discrimination in housing and recreation also began to be struck down. Many of these rulings came in cases brought by the NAACP. An increasing number of Black people began to move into all-white areas of Northern cities. Many whites then moved out of the cities to suburbs.

The NAACP and the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund won a historic victory in 1954. That year, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in the case of Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka that segregation in the public schools was in itself unequal and thus unconstitutional. The suit had been filed because the school board had not allowed a Black student named Linda Brown to attend an all-white school near her home. The court’s decision rejected the separate but equal ruling of 1896 and inspired African Americans to strike out against other discrimination, particularly in public places.

In 1955, Emmett Till, a Black teenager, was beaten and killed while visiting Money, Mississippi. Two white men were charged with the murder but were acquitted by an all-white jury. The men later admitted to the crime. Till’s murder sparked widespread outrage and led to increased support for the civil rights movement.

Rosa Parks, a seamstress and civil rights activist in Montgomery, Alabama, became a symbol of African Americans’ bold new action to attain their civil rights. In 1955, she was arrested for disobeying a city law that required Black riders to give up their bus seats when white people wished to sit in their seats or in the same row. Montgomery’s Black residents protested her arrest by refusing to ride the buses. Their protest began in late 1955 and lasted for over a year, ending when the U.S. Supreme Court declared segregated seating on the city’s buses unconstitutional. The boycott became the first organized mass protest by Black Americans in Southern history. It also focused national attention on its leader, Martin Luther King, Jr., a Montgomery Baptist minister.

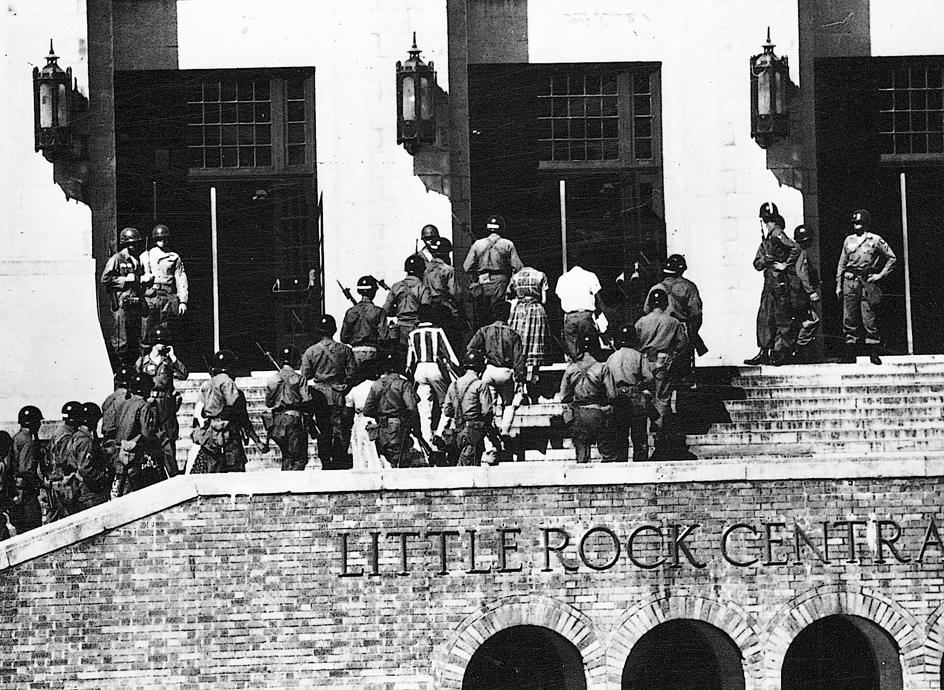

Many Southern communities acted slowly in desegregating their public schools. Governor Orval E. Faubus of Arkansas symbolized Southern resistance. In 1957, he defied a federal court order to integrate Little Rock Central High School. Faubus sent the Arkansas National Guard to prevent Black students from entering the school, but President Dwight D. Eisenhower used federal troops to enforce the court order.

The growing movement.

In 1957, King and other Black Southern clergymen formed the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) to coordinate the work of civil rights groups. King urged African Americans to use peaceful means to achieve their goals. In 1960, a group of Black and white college students organized the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) to help in the civil rights movement. They joined with young people from the SCLC, CORE, and the NAACP in staging sit-ins, boycotts, marches, and freedom rides (bus rides to test the enforcement of desegregation in interstate transportation). During the early 1960’s, the combined efforts of the civil rights groups ended discrimination in many public places, including restaurants, hotels, theaters, and cemeteries.

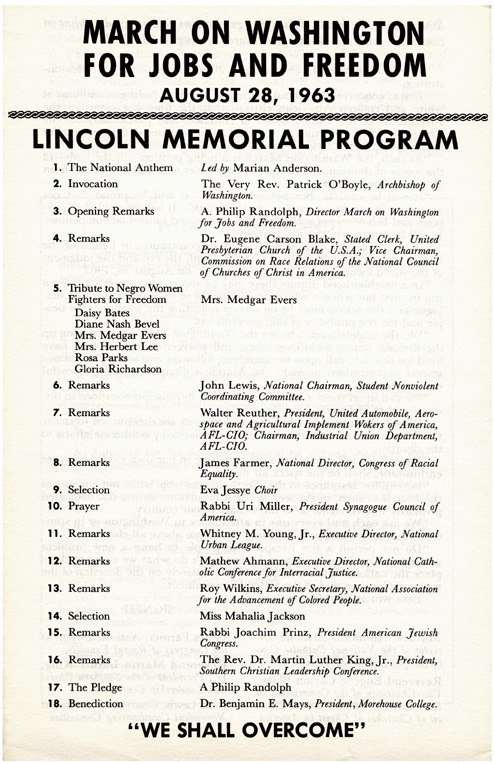

Numerous cities and towns remained unaffected by the civil rights movement. African American leaders therefore felt the United States needed a clear, strong federal policy that would erase the remaining discrimination in public places. To attract national attention to that need, King and such other leaders as A. Philip Randolph, Bayard Rustin, Roy Wilkins of the NAACP, James L. Farmer of CORE, and Whitney M. Young, Jr., of the Urban League organized a march in Washington, D.C., in August 1963. About 250,000 people, including many white sympathizers, took part in what was called the March on Washington.

A high point of the March on Washington was a stirring speech by King. He told the crowd that he had a dream that one day all Americans would enjoy equality and justice. Afterward, President John F. Kennedy proposed strong laws to protect the civil rights of all U.S. citizens. But many people, particularly Southerners, opposed such legislation.

Kennedy was assassinated in November 1963, and Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson became president. Johnson persuaded Congress to pass Kennedy’s proposed laws in the Civil Rights Act of 1964. This act prohibited racial discrimination in public places and called for equal opportunity in employment and education. King won the 1964 Nobel Peace Prize for leading nonviolent demonstrations for civil rights.

African American celebrities not directly involved with civil rights groups also contributed to the growing civil rights movement. Author James Baldwin criticized white Americans for their prejudice against Black people. Other noted African Americans who promoted civil rights causes included boxer Muhammad Ali, singer Harry Belafonte, dancer Katherine Dunham, comedian Dick Gregory, gospel singer Mahalia Jackson, and artist Charles White.

Political gains.

In the South, many elected officials and police officers refused to enforce court rulings and federal laws that gave Black citizens equality. In some cases, this opposition extended to the right to vote.

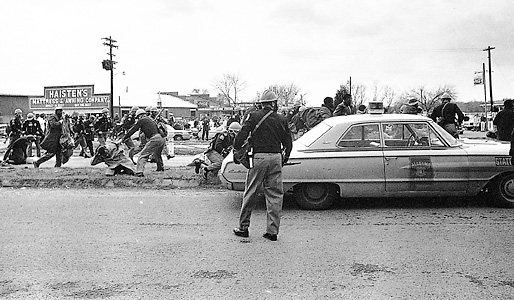

In 1965, a major dispute over voting rights broke out in Selma, Alabama. King had gone there in January to assist African Americans seeking the right to vote. He was joined by many Black and white people from throughout the country. In the next two months, at least three people were killed and hundreds were beaten as opposition to King’s efforts increased. Authorities continued to deny Black Americans their voting rights. In late March, King began leading about 3,200 people, guarded by federal troops, from Selma to Montgomery. By the time the marchers reached the Montgomery State Capitol Building, the crowd had grown to 25,000. There, King demanded that African Americans be given the right to vote without unjust restrictions.

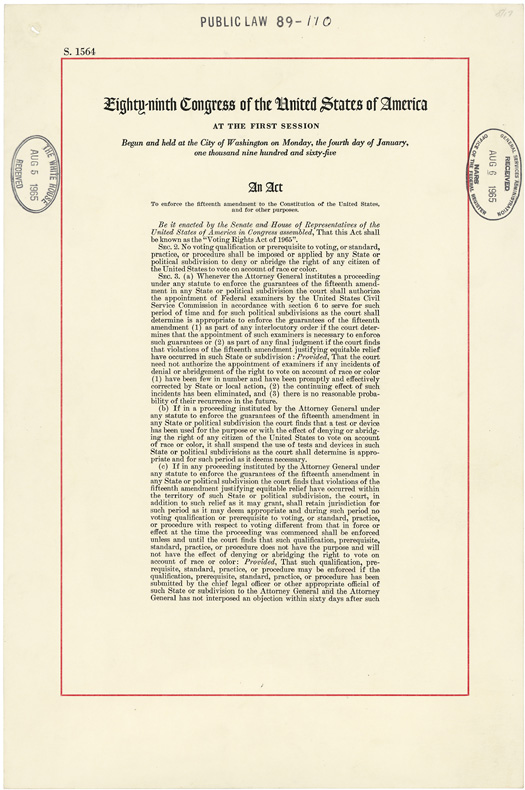

Largely as a result of the activities in Selma, Congress passed the Voting Rights Act of 1965. The act banned the use of a literacy test as a requirement to vote. The law also ordered the U.S. attorney general to begin court action that ended the use of a poll tax as a voting requirement. In places where voter registration had been unjustly denied, the Voting Rights Act provided for federal officials to supervise voter registration. The law also forbade major changes in voting laws without approval of the U.S. attorney general. The act gave the vote to hundreds of thousands of Southern Black citizens who had never voted. It thus led to a large increase in the number of Black elected officials.

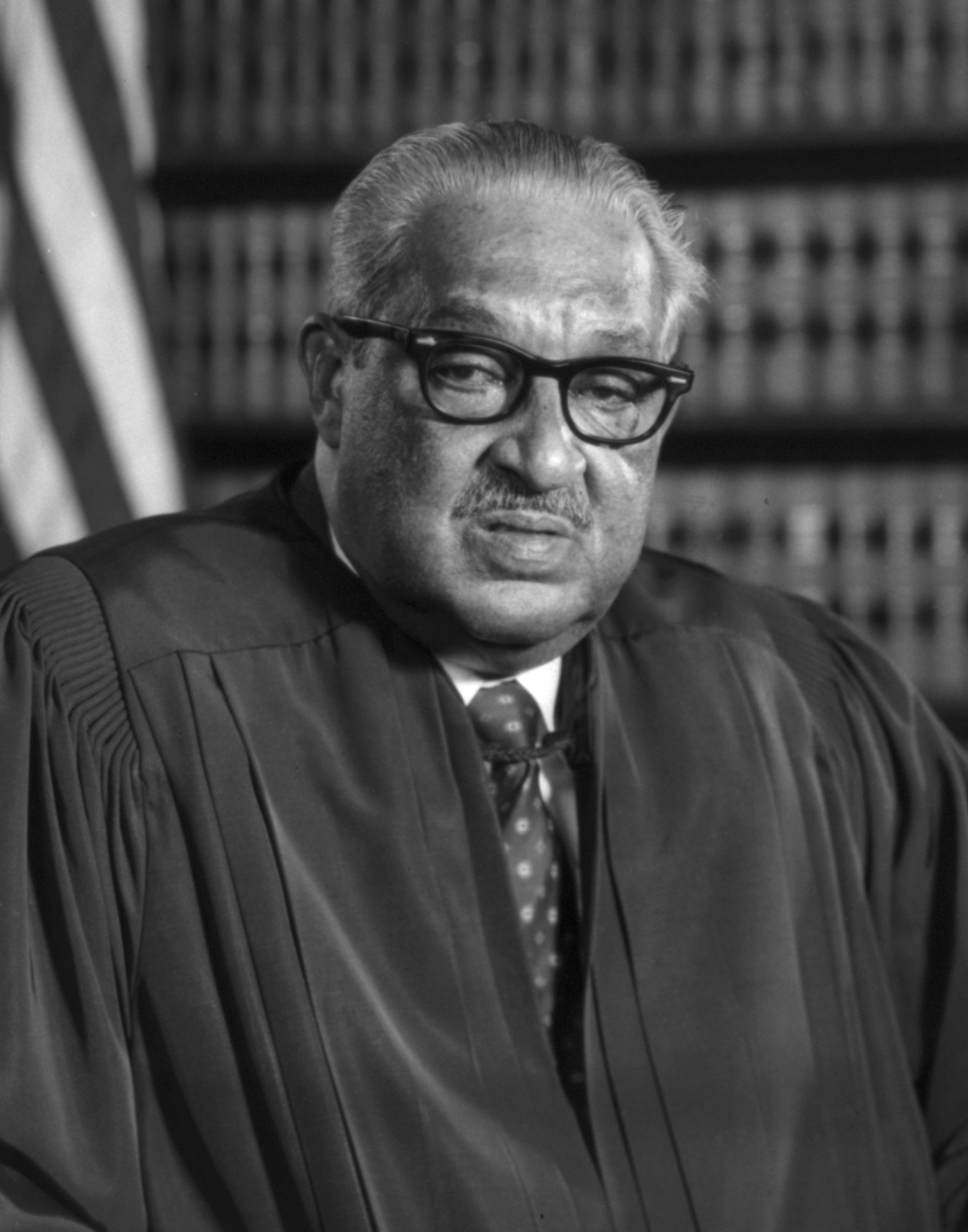

African Americans began to take an increasingly important role in the national government during the mid-1900’s. In 1950, U.S. diplomat Ralph J. Bunche became the first Black person to win the Nobel Peace Prize. In 1966, Robert C. Weaver became the first Black Cabinet member as secretary of housing and urban development. In 1967, Thurgood Marshall became the first Black justice on the Supreme Court. In 1969, Shirley Chisholm of New York became the first Black woman to serve in the U.S. House of Representatives.

Economic and social progress.

In 1965, President Johnson declared that it was not enough simply to end de jure segregation—that is, separation of the races by law. It was also necessary to eliminate de facto segregation—that is, racial separation in fact and based largely on custom. Johnson called for programs of “affirmative action” that would offer Black people equal opportunity with white people in areas where discrimination had a long history and still existed. Many businesses and schools then began to adopt affirmative action programs. These programs, some of which were ordered by the federal government, gave hundreds of thousands of Black Americans new economic and educational opportunities.

The new economic opportunities enabled many African Americans to increase their incomes significantly during the mid-1900’s. This development, in turn, greatly expanded the Black middle class.

Racial barriers fell in several professional sports and in the arts during the mid-1900’s. In 1947, Jackie Robinson of the Brooklyn Dodgers became the first Black player in modern major league baseball. He had an outstanding career and became a national hero. Other Black sports heroes of the mid-1900’s included Willie Mays, Hank Aaron, and Frank Robinson in baseball; Jim Brown and Gale Sayers in football; and Oscar Robertson, Bill Russell, and Wilt Chamberlain in basketball. In 1966, Russell became the first Black head coach in major league professional sports. He was named coach of the Boston Celtics of the National Basketball Association.

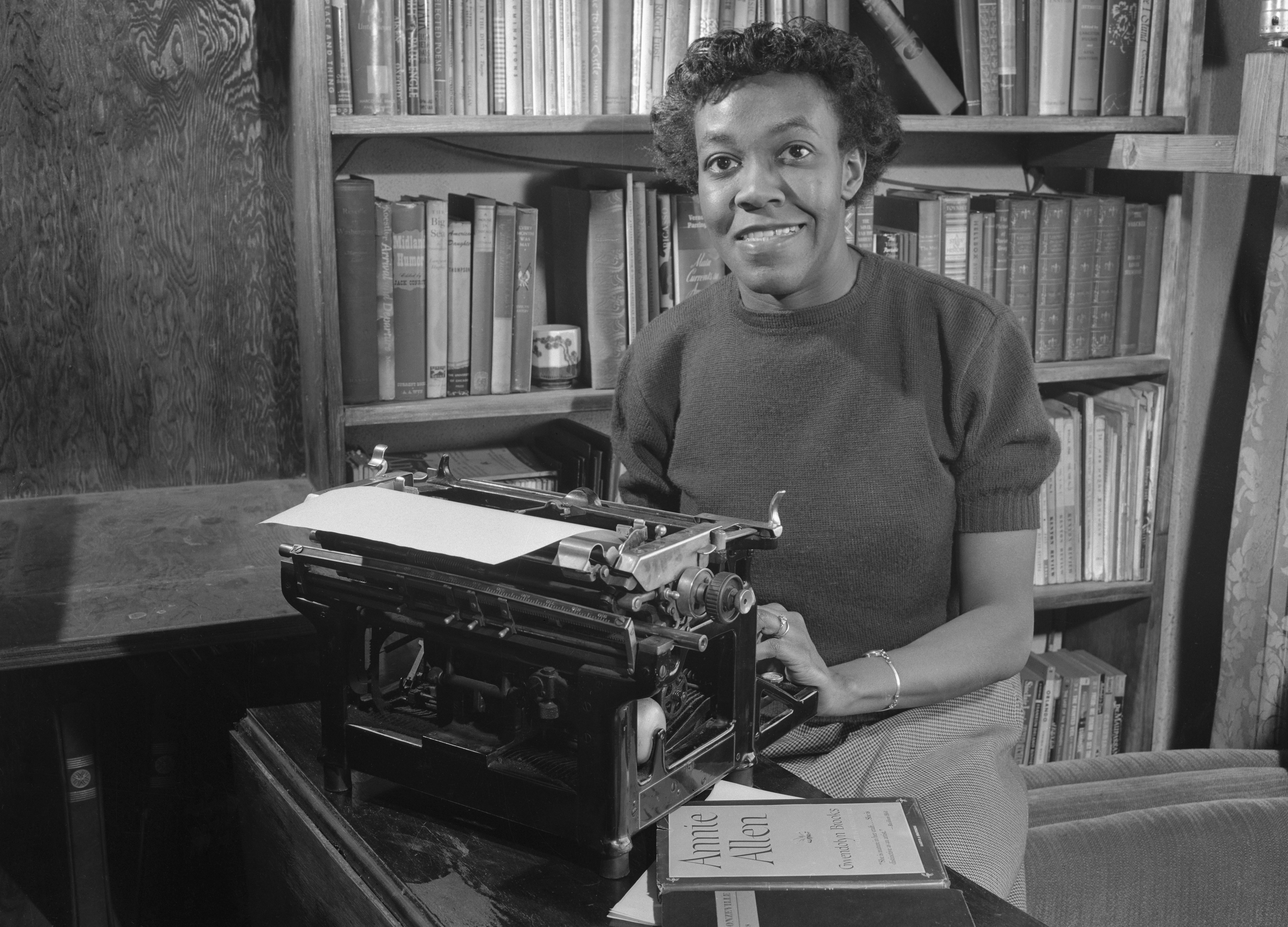

In the arts, Gwendolyn Brooks became the first African American to win a Pulitzer Prize. She received the award in 1950 for a collection of poems titled Annie Allen. In 1955, Marian Anderson became the first Black person to sing a leading role with the Metropolitan Opera in New York City. In 1958, Alvin Ailey formed one of the finest dance companies in the United States. In 1963, Sidney Poitier became the first African American to win the Academy Award for a leading role when he won the best actor award for Lilies of the Field.

Unrest in the cities.

Since the start of the civil rights movement, various court decisions, laws, and protests had removed great legal injustices long suffered by African Americans. But many Black people continued to be discriminated against in jobs, law enforcement, and housing. They saw little change in the long-held racist attitudes of numerous white Americans.

During the 1960’s, unrest among Black people living in urban ghettoes exploded into a series of riots that shook the nation. The first riot occurred in Harlem in the summer of 1964. In August 1965, 34 people died and almost 900 were injured in an outburst in the Black ghetto of Watts in Los Angeles. During the next two summers, major riots erupted in numerous cities across the nation.

The race riots puzzled many people because they came at a time when African Americans had made huge gains in the campaign for full freedom. In 1967, President Johnson established a commission headed by Governor Otto Kerner of Illinois to study the causes of the outbreaks. In its March 1968 report, the Kerner Commission put much of the blame on racial prejudice of white Americans. It said that the average Black American was still poorly housed, poorly clothed, underpaid, and undereducated. African Americans, the report said, still often suffered from segregation, police abuse, and other forms of discrimination. The commission recommended vast programs to improve ghetto conditions and called for greater changes in the racial attitudes of white Americans.

Less than a month after the Kerner Commission report was issued, race riots broke out in at least 100 Black communities across the nation. The rioting followed the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., on April 4 in Memphis, Tenn. James Earl Ray, a white drifter, was convicted of the crime and sentenced to 99 years in prison. King’s murder helped President Johnson persuade Congress to approve the Civil Rights Act of 1968. This law, also known in part as the Fair Housing Act of 1968, prohibited racial discrimination in the sale and rental of most of the housing in the nation.

Black militancy.

During the height of the civil rights movement, some Black Americans claimed that it was almost impossible to change white racial attitudes. They saw the movement as meaningless and urged Black people to live apart from white people and, in some cases, to use violence to preserve their rights. Groups promoting these ideas included the Black Muslims, the Black Panthers, and members of the Black Power Movement.

The Black Muslims had been led since 1934 by Elijah Muhammad, who called white people “devils.” He also criticized racial integration and urged formation of an all-Black nation within the United States. But the most eloquent spokesman for the Black Muslims during the 1950’s and 1960’s was Malcolm X. Malcolm wanted to unite Black people throughout the world. He was assassinated in 1965 after forming a new organization to pursue his goal. Three Black men, at least two of whom were Black Muslims, were convicted of the murder.

The Black Panther Party was founded in 1966. Its two main founders, Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale, had been inspired by Malcolm X. At first, the party favored violent revolution as the only way to end police actions that many Black people considered brutal and to provide opportunities for African Americans in jobs and other areas. The Panthers had many clashes with police and others. Later, the party became less militant and worked to achieve full employment for Black workers and other peaceful goals.

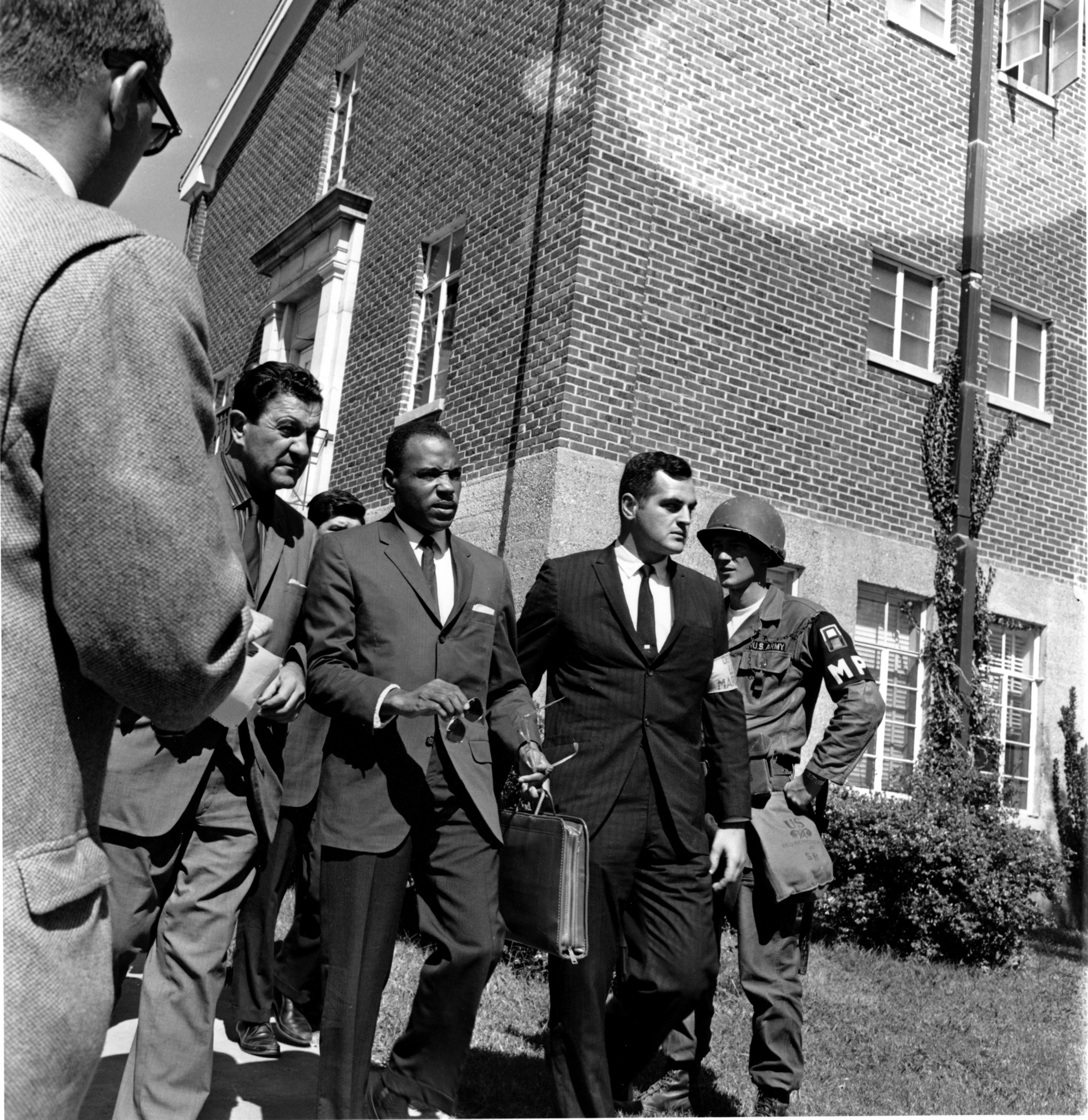

The Black Power Movement developed in 1966 after James H. Meredith, the first African American to attend the University of Mississippi, was shot during a march. The shooting and other racial violence made Stokely Carmichael, H. Rap Brown, and other members of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) doubt the sincerity of white support for Black rights. Such doubts prompted SNCC to expel its white members.

Carmichael and other African Americans called for a campaign to achieve “Black Power.” They urged Black people to gain political and economic control of their own communities and to reject the values of white people. The leaders stressed that “black is beautiful” and called on Black people to form their own standards. They suggested that Black Americans no longer refer to themselves as Negroes or colored people but as blacks, African Americans, or Afro-Americans.

Beyond the civil rights movement

Developments since 1970.

African Americans have achieved great progress in education and politics since the 1970’s. Many have also won great recognition in such fields as sports and the arts.

Education.

From 1970 to the first decade of the 2000’s, college enrollments among African Americans rose from about half a million to about 2 million students. This gain resulted in part from affirmative action programs by predominantly white colleges and universities. By the first decade of the 2000’s, about 20 percent of all Black Americans had received a bachelor’s degree.

A Black studies movement emerged on college campuses throughout the nation during the 1970’s and drew increasing attention to the heritage of African Americans. In addition, Black musical and theater groups and African American museums were established in almost every U.S. city with a fairly large Black population.

In the 1980’s and 1990’s, courses of study based on an approach called Afrocentrism gained popularity. These courses aimed to teach the culture and history of Africans and African Americans. Educators soon developed a broader curriculum called multicultural education, designed to help students from all backgrounds appreciate diverse cultures and peoples. Most of the programs emphasize the past and present accomplishments of African Americans and other groups. Educators think it is important to recognize the injustices that have sometimes been suffered by African Americans and other minority groups. Many educators also believe that such teaching builds the self-esteem of African American children and improves their success in school.

Another trend in education is the growing acceptance, among many educators, of African American English (AAE), a variation of English spoken by many Black Americans. AAE is also called Black English, Ebonics (ee BAHN ihks), African American Language (AAL), and African American Vernacular English (AAVE). Educators have developed courses to teach the grammatical rules, pronunciation, and vocabulary of AAE. A knowledge of AAE can help teachers improve their instruction of African American students. Some schools also employ it as an aid in the teaching of standard English.

Affirmative action.

Supreme Court decisions from the 1970’s to the early 2000’s sharply limited affirmative action programs. In 1978, the court ruled that racial quotas could not be used in admitting students to colleges and universities. In 1995, it ruled that federal programs requiring preferences based on race are unconstitutional unless preferences are designed to make up for specific instances of past discrimination. This meant that affirmative action could no longer be used to counteract racial discrimination by society as a whole. In 1989, the court had made a similar decision regarding state and local affirmative action programs.

The 1995 ruling was supported by Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas, an African American who replaced Thurgood Marshall on the court when Marshall retired in 1991. Thomas had long been an outspoken opponent of affirmative action. He based his opposition on the principle that the government may not treat individuals differently based on race. Many other Black Americans, however, continued to believe that broad affirmative action programs were needed to help minorities overcome past discrimination and eventually compete on an equal basis with white Americans. In 2003, the Supreme Court ruled that, within certain limits, colleges and universities could use race as a factor in selecting students for admission.

Politics.

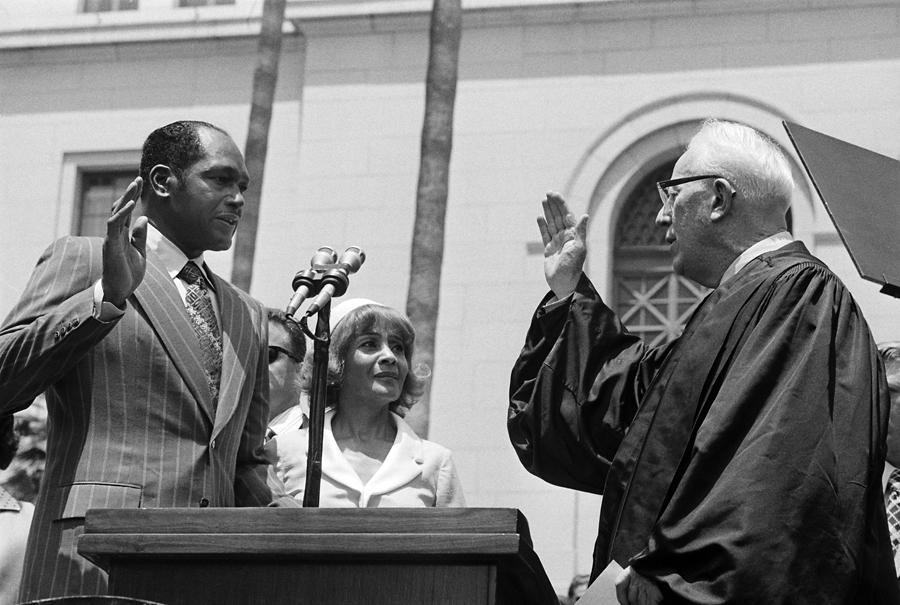

Many African American leaders stressed the use of political means to solve the problems of Black people. They urged more African Americans to vote and to run for public office. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 led to the removal of restrictions on voting in most places. As a result, African Americans helped elect a greater number of Black candidates to public offices. In 1973, for example, Tom Bradley was elected the first Black mayor of Los Angeles.

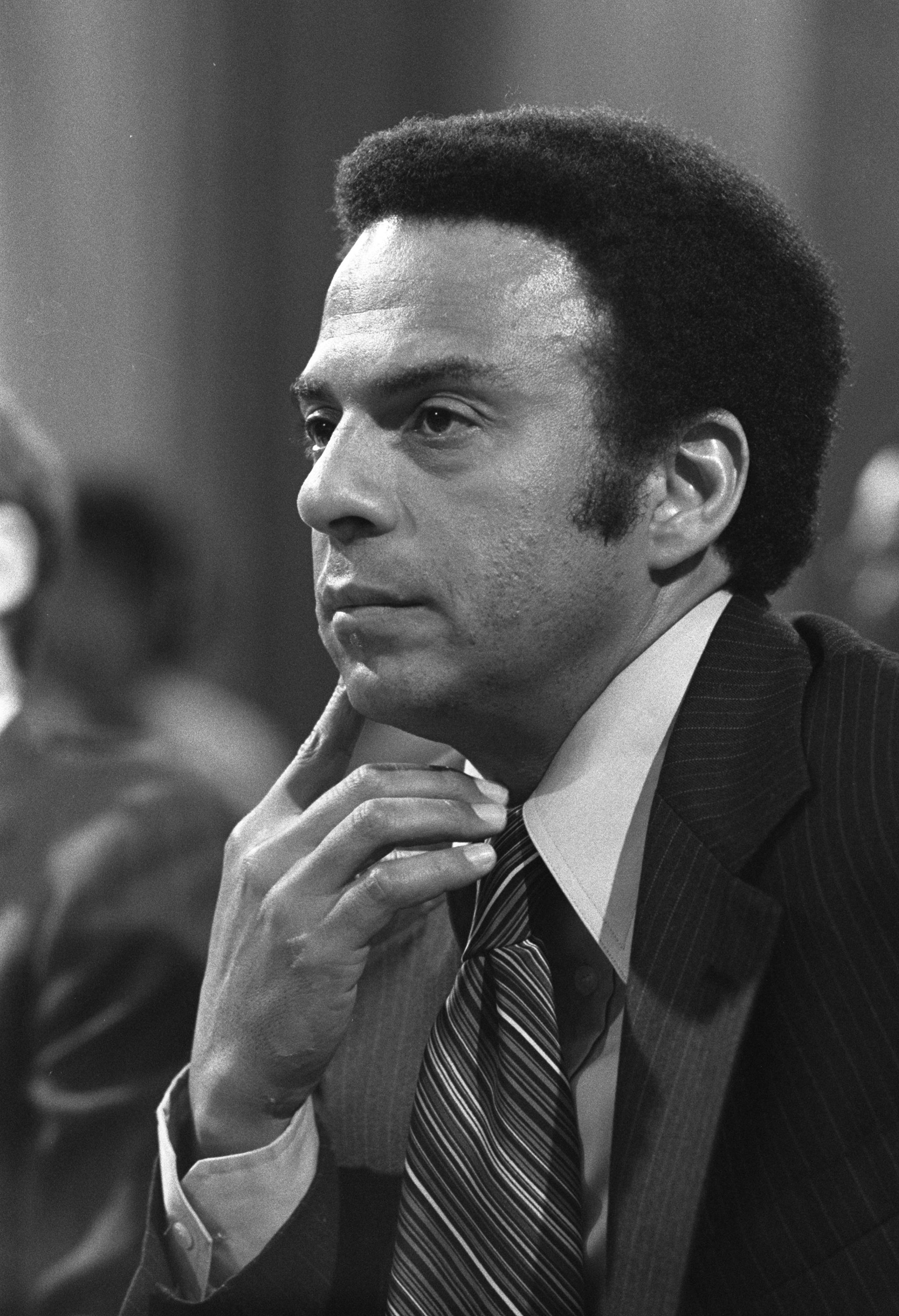

African Americans gained considerable influence in the administration of Jimmy Carter, who was president of the United States from 1977 to 1981. Under him, Andrew Young became the first Black U.S. ambassador to the United Nations (UN). Carter named Patricia Roberts Harris secretary of housing and urban development. She was the first Black woman to hold a Cabinet post.

In 1984 and 1988, Jesse L. Jackson, a Black civil rights leader and Baptist minister, waged a strong campaign to register new Black voters and win the Democratic presidential nomination. Jackson failed to win the nomination, but he became a hero to many African Americans.

In the 1990’s, many African Americans focused on self-help programs to deal with crime, drug abuse, poverty, and substandard education. For example, in 1995, hundreds of thousands of Black men marched in Washington, D.C., to declare their determination to improve conditions in Black communities. Crowd estimates ranged from 400,000 to more than a million. The event, called the Million Man March, was organized chiefly by Louis Farrakhan, leader of the Nation of Islam, a Black Muslim group.

Current challenges.

Despite the considerable progress that African Americans have made since the civil rights movement began, many Black people continue to face economic struggles and other challenges. The Black middle class has expanded, but other African Americans live at the extremes of both wealth and poverty. Black entertainers and athletes have become enormously wealthy in the decades since the 1960’s. But a significant number of Black Americans remain poor, isolated, and vulnerable to disease, drugs, crime, discrimination, and racism.

Housing and lending discrimination.

Although housing discrimination occurs far less frequently than in the past, African Americans often live in the poorest communities with the least resources. Lenders often charge Black homeowners higher interest on mortgage loans than white homeowners. Higher monthly payments sometimes mean severe economic strain for struggling Black families. During the economic recession of the first decade of the 2000’s, a large number of African Americans faced the risk of losing their homes to foreclosure. Many Black people became the victims of dishonest lending agencies that were more interested in selling houses than in the ability of their clients to pay for them.

Health issues.

A large number of Black people have suffered from diseases associated with poverty, lack of education, and limited access to health care. Black Americans have been much more likely than white Americans to contract HIV/AIDS. In the 2010’s, nearly half of newly diagnosed HIV/AIDS patients in the United States were African Americans. In the 2020’s, Black Americans were about twice as likely as white Americans to die of the respiratory disease COVID-19.

Black Americans are also more likely to have diabetes than non-Hispanic whites are. In the first decade of the 2000’s, more than 10 percent of all African Americans aged 20 years or older had the disease. In addition, Black American children and adults are three times more likely than white Americans to be hospitalized for asthma and to die from asthma. Substandard housing, resulting in increased exposure to certain indoor allergens (substances that cause allergies), contributes to an increased risk of asthma among some Black people.

Social struggles.

Reductions in government spending have led to cutbacks in education and social programs, often hitting poor Black communities the hardest. In addition, changes in the U.S. economy, including the decline of manufacturing, have contributed to high unemployment rates among African Americans. A high dropout rate in schools leaves many young people unprepared for new types of well-paying jobs requiring technical skills. Unemployment and poverty are often linked with criminal behavior, and in these situations, African American males are especially at risk. Black-on-Black violence—much of it gang-related—continues to plague poorer African American communities.

In 1980, about 145,000 African American men were in prison. Twenty-five years later, there were about four times that many. Many social scientists believed that a major cause of this increase in the imprisonment rate was a U.S. government policy called the War on Drugs. The War on Drugs, begun in the 1970’s, sought to reduce the illegal drug trade by imposing mandatory (required) prison sentences for drug possession. Some social scientists also saw racial bias in new laws imposing stiffer sentences for crack cocaine than for powder cocaine. Crack cocaine is a form of cocaine that is smoked, and it is more likely to be used by Black people. Powder cocaine is usually snorted through the nose or injected, and it is more likely to be used by whites. In 2010, Congress passed a law that brought federal crack cocaine sentences in line with those for powder cocaine.

Race relations.

In 1992, riots broke out in Los Angeles and other U.S. cities. The riots erupted after a jury decided not to convict four white police officers of assaulting an African American motorist named Rodney G. King . No African Americans had served on the jury. The jury’s decision shocked many people because a videotape showing the officers beating King had been broadcast by TV stations throughout the country. Many African Americans felt the trial proved that the U.S. court system treated Black people unfairly. Fifty-three people died and over 4,000 were injured in the Los Angeles riots . Later that year, all four officers were indicted under federal laws for violating King’s civil rights. Two of the officers were convicted in 1993.

Barack Obama’s election to the presidency in 2008 was a historic milestone. His election stood as an example of the progress that came from the civil rights movement. Many Americans became hopeful that racism had diminished in the United States. Despite this progress, racial tensions still lingered.

Several incidents in 2014 highlighted tensions between police forces and African American communities in the United States. In July, Eric Garner, an African American man under arrest for a misdemeanor charge, died after a white police officer held him across the neck in a choke hold. In the following months, police use of force led to the deaths of Black teenagers Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, and LaQuan McDonald in Chicago; and of 12-year-old Tamir Rice in Cleveland, Ohio. People protested both the shootings and what many believed was a history of unfair treatment of Black people by white authorities. The protests at times involved damage to property, and national media broadcast images of protesters pitted against police clad in riot gear. The activist group Black Lives Matter, formed to campaign against racial injustice and police brutality, gained in prominence during the protests.

Other much-reported deaths resulting from police use of force included: Freddie Gray of Baltimore, Maryland, in 2015; Alton Sterling of Baton Rouge, Louisiana, and Philando Castile of Falcon Heights, Minnesota, in 2016; and Breonna Taylor of Louisville, Kentucky, and George Floyd in Minneapolis, Minnesota, in 2020. Some of the killings were captured in videos that were then shared on social media. Following some of these incidents, police officers faced criminal charges, and police chiefs were fired or resigned. In addition, a number of police officers were wounded or killed in retaliatory attacks.

The killings and the protests sparked a national dialogue about relations between police and minority groups, and racial bias in criminal proceedings, employment, and social settings. Politicians regularly issued calls for reform and police retraining. Prominent athletes and entertainers promoted calls to end racial injustice. Increased media attention about such issues, however, led to a backlash among many conservative white Americans, including communities with strong ties to police. Commentators pointed to high rates of violent crime in poor Black communities and promoted images of the looting that followed some protests. The challenges confronting the African American community, especially its poorest members, seemed likely to persist for years to come.