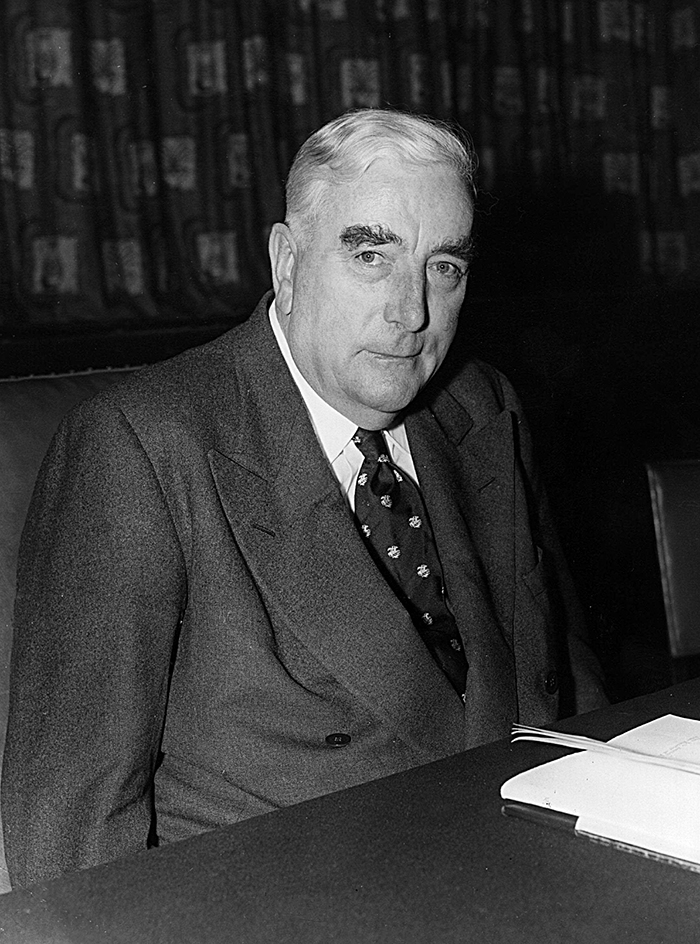

Menzies, << MEHN zeez, >> Sir Robert Gordon (1894-1978), served as prime minister of Australia from 1939 to 1941 and from 1949 to 1966. He served for more than 18 years—longer than any other prime minister in Australian history. Menzies held the office during Australia’s entry into World War II (1939-1945) and later dominated Australian political life during the 1950’s and 1960’s. He helped found the Liberal Party of Australia and was a fierce opponent of Communism.

As prime minister, Menzies presided over great changes in the Australian way of life. During his second prime ministership, the Australian economy grew steadily, particularly in manufacturing, and the average Australian citizen prospered. Menzies’s time in office and period of influence is sometimes called the “Menzies Era” in Australian history.

Early life and family

Robert Gordon Menzies was born on Dec. 20, 1894, in the small town of Jeparit, near Dimboola, in the British colony (later the Australian state) of Victoria. He was the fourth of five children born to James and Kate Menzies. James Menzies was a storekeeper and lay preacher in the local Presbyterian church. He also held a seat in the Victorian Parliament. Young Robert—familiarly known as Bob—learned to read at an early age and quickly became a lover of books.

Menzies attended Wesley College in Melbourne and later the University of Melbourne. He studied law and won many scholarly prizes. He also served as editor of Melbourne University Magazine and president of the Students’ Representative Council. He graduated with first-class honors in 1916 and became a barrister (lawyer who argues cases in higher courts) in 1918. Menzies then began a prosperous legal practice, specializing in constitutional law. In 1920, he gained recognition for winning a case in the High Court of Australia that expanded Commonwealth powers over the states.

On Sept. 27, 1920, Menzies married Pattie Maie Leckie (1899-1995), daughter of John William Leckie, a manufacturer and politician. The couple had three children: Kenneth (born in 1922); Ian (born in 1923); and Heather (born in 1928), who married Peter Henderson, an Australian diplomat.

Political career

During the 1920’s, Menzies was active in the Victorian branch of the Nationalist Party, forerunner of the United Australia Party (UAP). On Oct. 6, 1928, Menzies was elected to the Legislative Council, the upper house of the Victorian Parliament. In 1932, he was appointed deputy premier of Victoria, as well as the state’s attorney general (chief legal officer) and minister for railways.

Becoming prime minister.

On Sept. 15, 1934, Menzies won the Kooyong seat in the Australian House of Representatives. He would hold this seat until he retired from politics in 1966. Menzies was also appointed federal attorney general and minister for industry in the government of Prime Minister Joseph Lyons. In December 1935, Menzies became deputy party leader of the UAP. In 1937, he was appointed to the Privy Council, the British sovereign’s private council. On March 14, 1939, Menzies resigned as attorney general and deputy party leader over the government’s rejection of a national insurance plan that he strongly supported.

On April 7, Prime Minister Lyons died of a heart attack—the first Australian prime minister to die in office. Earle Page briefly held the office as a caretaker until the UAP elected a new party leader. The UAP chose Menzies, and he became prime minister on April 26, 1939.

World War II.

On September 3, just a few months after taking office, Menzies told the Australian people that, “…in consequence of a persistence by Germany in her invasion of Poland, Great Britain has declared war upon her and that, as a result, Australia is also at war.” Australia thus followed the United Kingdom into World War II.

In October 1940, Menzies formed an Advisory War Council, including several members of the opposition Australian Labor Party. He also announced the recruitment of an army for service in Australia and abroad, and called up local militias. The Australian government viewed Australian residents of German, Italian, and, later, Japanese descent as a potential threat to the welfare of the country. As a result, many of these Australians were sent to internment camps.

Menzies introduced censorship, price controls, rationing, and military conscription (draft) for home defense. In 1940, Menzies banned the Communist Party. The ban was lifted in late 1941, however, after the German invasion of the Soviet Union made the Soviet Union a British ally.

During the next two years, Menzies and his government faced severe criticism for not doing enough to prepare Australia for war. Some UAP members joined in the criticism. In February 1941, Menzies visited the United Kingdom, where he attended meetings of the British War Cabinet. He also asked the United Kingdom for reinforcements to help defend Australia in the coming war with Japan and for assistance in the rapid industrialization of the Australian economy. But he received no British aid.

When Menzies returned to Australia in May 1941, his support had dwindled. The UAP was slipping away from him, and he feared that disagreements within the party might hamper the nation’s war effort. After appealing in vain to the Labor Party for a coalition government, Menzies resigned as prime minister on Aug. 29, 1941. He also resigned as UAP leader. John Joseph Curtin of the Labor Party served as prime minister for most of the rest of the war.

Menzies regained the UAP leadership in September 1943, when the party was reeling after a poor performance in that year’s national election. In October 1944, Menzies combined the forces opposed to the ruling Labor Party, creating the Liberal Party of Australia under his leadership. The Liberal Party promoted free enterprise—that is, less government regulation of the economy. The party was firmly antisocialist, but also supported the emerging consensus that government had some responsibility for improving social conditions. World War II ended in 1945, but the Labor government’s popularity waned as wartime restrictions continued. In the years following World War II, tensions mounted between the world’s Communist and non-Communist countries, leading to the start of a period of international tension called the Cold War.

Return to power.

In October 1947, Menzies and the Liberals successfully opposed a bill proposed by the Labor government intended to nationalize private banks. Against the background of the escalating Cold War, Menzies and the Liberal Party branded the faltering Labor Party as Communist sympathizers. In late 1949, the Liberals won the national election. On December 19, Menzies began his second prime ministership.

Public fears of unchecked Communism worsened as a result of international events, including a Soviet blockade of Berlin, the victory of the Communist party in China, and the outbreak of the Korean War (1950-1953). Menzies played up to these fears, warning of a likely third world war. He renewed his efforts to ban the Communist Party, passing the Communist Party Dissolution Act in October 1950. In March 1951, however, the High Court of Australia declared the act invalid because the government did not have constitutional powers to ban a political party in peacetime. Menzies again tried to outlaw the Communist Party by a referendum (vote) to change the Constitution in September 1951, but this effort narrowly failed.

Menzies continued his assault on Communism by sending Australian troops to fight alongside United Nations forces in Korea. In 1955, Australians fought Communist forces in Malaya (now Malaysia). Some 50,000 Australian soldiers later fought against the Communist forces of North Vietnam in the Vietnam War from 1962 to 1972.

Prosperity at home.

During Menzies’s second prime ministership, Australia—along with most other developed nations—achieved steady economic growth. As Australia’s population grew, so did the ownership of automobiles, homes, and modern household appliances. Menzies became popular among members of Australia’s growing middle class. He encouraged European immigration to Australia and the development of transportation and natural resources. He expanded the education system and increased the resources devoted to the arts, humanities, and science. He also spurred the development of Canberra as the national capital of the commonwealth.

Menzies had lifelong admiration for the British. He had a particular affection for the royal family. As prime minister, he hosted Queen Elizabeth II on visits to Australia in 1954 and 1963. In 1963, the queen made him a knight of the Order of the Thistle, the second highest order a British monarch can bestow. In 1965, Menzies received the honorary title Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports, succeeding the British statesman Sir Winston Churchill (see Cinque Ports ).

Later years

After winning five general elections, Menzies retired from politics on Jan. 26, 1966, at the age of 71. He was succeeded by Harold Holt of the Liberal Party. On Nov. 30, 1971, Menzies suffered a severe stroke that left him largely incapacitated. He died in his home at Malvern, a suburb of Melbourne, on May 15, 1978. In June 1996, Menzies’s ashes were placed in the Prime Ministers Memorial Garden in Melbourne General Cemetery.

See also Australia, History of (World War II (1939-1945)) ; Australia, History of (Postwar Australia) ; Petrov Affair .