English Civil War was fought between the forces of King Charles I and those of the English Parliament. The war took place in two parts. The first part lasted from 1642 to 1646, the second from April to November 1648. The war led to the execution of Charles I in 1649 and a period of more than 11 years when no monarch (king or queen) ruled England.

Causes of the Civil War

Before the Civil War, the English monarch ran the national government of England with the aid of ministers. Parliament took a less important part in state affairs than it does today. The first Stuart king, James I, reigned from 1603 to 1625. During that time, a distrust of the monarchy developed within Parliament. His son, Charles I, called three parliaments between 1625 and 1628 and had trouble with each. After dissolving (ending) the third in 1629, he ruled without Parliament until 1640.

Economic causes.

Inflation forced up prices in all parts of Europe between 1530 and 1640. It drastically reduced the value of the monarch’s income. James I spent money lavishly, but Parliament refused to give him more. He responded by levying new import duties.

In 1625, Parliament refused to grant Charles I tonnage and poundage—that is, the customs duties that normally provided much of the monarch’s income. Charles forced property owners to lend him money and imprisoned those who refused. In 1628, Parliament passed the Petition of Right, forbidding the king to raise any taxes without its consent. Charles accepted the petition but insisted that it did not apply to customs duties. In the 1630’s, he evaded the petition by collecting ship money. Ship money was a form of tax imposed on seaside towns and counties to provide ships for the Royal Navy. Charles extended the tax to inland towns and counties.

Religious causes.

For many years, a radical group within the Church of England, the Puritans, sought to do away with bishops and revise the Prayer Book. Although James I resisted the Puritans, he wanted to mediate the divisions within the Anglican Church. Charles I took a much narrower view, as shown by his choice of William Laud, an ardent opponent of Puritanism, as archbishop of Canterbury in 1633. The Puritans accused Charles and Laud of leaning toward Roman Catholicism. Charles’s wife, Henrietta Maria, was unpopular because she was Catholic and because she was the sister of Louis XIII of France. Laud was also unpopular, because he encouraged Charles’s belief in the divine right of kings—that is, the idea that kings were appointed by God and ruled on God’s behalf.

War with the Scots.

In 1638, the Scots rebelled against Charles when he tried to impose the English Prayer Book on their Presbyterian Church. Charles mounted an expensive campaign against the Scots in 1639, but it failed. His most able minister, the Earl of Strafford, advised him to summon a parliament to raise money for another campaign in Scotland. The Short Parliament met in April 1640 but refused to approve further taxes until the king dealt with its complaints. Strafford advised Charles to dissolve the session after only three weeks. The Scots then invaded northern England and forced Charles to buy a truce. To do so, Charles had to recall Parliament.

The first session of the Long Parliament lasted from November 1640 to September 1641. Led by John Pym, it passed laws making ship money illegal and abolishing the courts of Star Chamber and High Commission. It impeached Strafford, and he was executed in 1641. The session also forced Charles to agree to call Parliament every three years, with the further provision that he could not dissolve Parliament without its own consent.

The final crisis

began with the outbreak of a rebellion of Roman Catholics in Ireland in November 1641. Charles wanted to raise a new army to subdue Ireland, but Parliament did not trust him to command it. Instead, Parliament passed the Grand Remonstrance, which attacked the king’s policies of the past 10 years, called for radical reform of the Church of England, and demanded the right to control the appointment of ministers. In January 1642, Charles ordered the impeachment of five members of Parliament, including John Pym and John Hampden. When Parliament refused to surrender the five, Charles invaded the Commons chamber in person—a breach of parliamentary privilege. The five had already left to take shelter in the City of London.

Surrounded by enemies in London, Charles left the capital to seek support in the provinces. In March, he refused to give up control of the army. In June, Parliament began raising its own army. It also sent Charles Nineteen Propositions, a document that amounted to terms for his surrender.

Charles raised the royal standard at Nottingham in August. The first clash had already taken place at Manchester in July. By September, fighting had broken out between Royalists—supporters of the king—and supporters of Parliament in all parts of the country.

Cavaliers and Roundheads

The Royalists became known as the Cavaliers, and the supporters of Parliament came to be called the Roundheads. The word Cavalier comes from the French word for horseman or knight. The word reflects the fact that the Royalists were at first superior in cavalry. The term Roundhead originally referred to the parliamentary infantryman, with his hair cut short to fit his casque (steel helmet). By the end of the Civil War, the armies of Parliament were superior in cavalry and infantry.

The two sides were not based on differences in class. Parliament could call on as many nobles and gentry as could the king. Many families included supporters of both sides.

Parliament’s control of London and most of the other important towns gave it a distinct advantage. It raised war funds through taxation. The king had to rely on voluntary contributions. Parliament won because it was able to finance a professional army.

The first phase

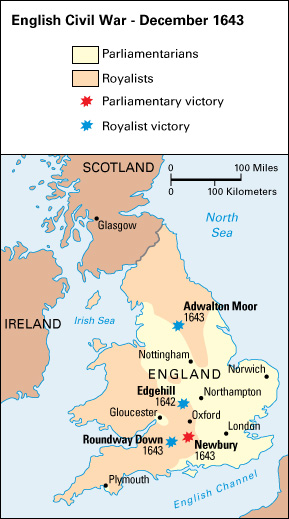

The parliamentary army assembled at Northampton in September 1642, under the Earl of Essex. Leaving Nottingham, Charles marched through Chester and Shrewsbury, recruiting an army roughly equal to Essex’s. The two armies clashed at Edgehill, in the county of Warwickshire, on October 23. The king’s nephew, Prince Rupert, led the cavalry brilliantly, and the king won. But his attack on London in November failed. Charles pulled back to Oxford.

In 1643, the parliamentary army under Essex spent most of the summer trying to advance on Oxford. In the north, a Royalist army under the Earl of Newcastle smashed a parliamentary army under Ferdinando and Thomas Fairfax at Adwalton Moor, near Leeds (June 30). Then, in the west, a Royalist army under Sir Ralph Hopton defeated Sir William Waller at Roundway Down, in Somerset (July 13).

Leaders in Parliament feared that Hopton and Newcastle would join forces with Charles and attack London. They decided to turn to the Scots for help, signing the Solemn League and Covenant in September. The document was a league (treaty) against the king and a covenant (promise) of church reform. The Scots crossed the border in January 1644.

The Royalist armies never joined forces. The Earl of Newcastle’s army was blocked by Parliament’s East Anglian forces, called the Eastern Association, commanded by the Earl of Manchester. Hopton’s army captured Bristol, but could do no more. Charles besieged Gloucester for a time and then lost the first Battle of Newbury (Sept. 20, 1643).

In 1644, Royalist forces defeated Waller at Cropredy Bridge, near Banbury, in Oxfordshire (June 29). But, in the north, the Scots drove the Royalists under the Earl of Newcastle into York. Parliamentary forces under the Fairfaxes and the Eastern Association army, commanded by Oliver Cromwell, joined the siege. Charles ordered Prince Rupert to relieve York. On July 2, though outnumbered by a 3 to 2 ratio, the Royalists fought the Parliamentarians and Scots on Marston Moor. They lost the bloodiest battle of the war mainly because Cromwell defeated the Royalist cavalry under Lord Goring.

The Earl of Essex led a parliamentary army into Cornwall, but was trapped at Lostwithiel. He escaped by boat, leaving most of his army to surrender. The Earl of Manchester marched south, but was outmaneuvered by a much smaller Royalist army. Charles won the second Battle of Newbury (October 27).

Montrose.

The chronic bad feeling between the Scots and the English led to endless disputes. The Scots moved no farther south than Newark. Then they had to send a large part of their army back north to deal with the Marquess of Montrose, who had persuaded the Highland clans to rebel against the Scottish government in the king’s name in September 1644. Montrose then conducted a brilliant guerrilla campaign, occupying Glasgow in August 1645. But he was defeated at Philiphaugh (Sept. 13, 1645). His army broke up and he fled abroad.

The New Model Army.

In the winter of 1644 and 1645, Cromwell led a fierce campaign to purge the high command. Parliament passed the Self-Denying Ordinance, which required all members of both Houses to resign their commissions. The ordinance seemed designed to keep politics out of the military command. But Cromwell’s friends in Parliament had him reappointed. They also persuaded Parliament to establish a full-time professional army, the New Model, under Sir Thomas Fairfax, with Cromwell as general of horse.

The New Model Army was irresistible. At the Battle of Naseby, in Northamptonshire (June 14, 1645), it destroyed the king’s main field army. It then destroyed the western army under Goring at Langport, in Somerset (July 10). Rupert surrendered Bristol, and organized Royalist resistance collapsed. In April 1646, Charles left Oxford in disguise and surrendered to the Scots’ army at Newark (May 5). The Scots retreated with him to Newcastle.

The second phase

No peace treaty was signed, because both Parliament and the Scots had always claimed that they were fighting to free the king from his wicked advisers, not fighting the king himself. They proposed constitutional safeguards to restrict the king’s choice of ministers and his control of the army.

The Scots withdrew from northern England and surrendered Charles to the Parliamentarians in January 1647, in return for a large sum of money. Parliament was by then having trouble controlling the New Model Army, which objected to being demobilized without full pay and an amnesty. The army had been infiltrated by a group of extreme radicals, the Levellers. Led by John Lilburne, the Levellers wanted to abolish the kingship and the House of Lords and to create a democratic and decentralized government. They also wanted radical social reform.

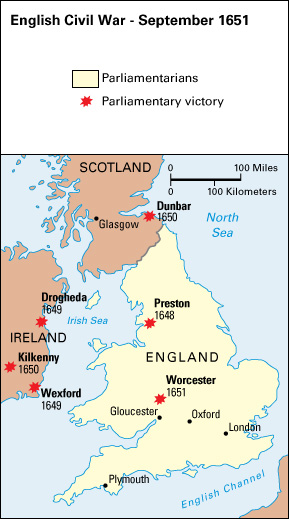

Army officers kidnapped Charles in June, and in August the army occupied London and expelled its chief opponents from Parliament. Cromwell tried to persuade Charles to accept a compromise scheme, called the Heads of the Proposals, which made concessions to him as well as the Levellers. But in November, Charles escaped to Carisbrooke Castle, on the Isle of Wight. There he sought help from dissident Scottish nobles. War broke out again in 1648, but it was speedily over. Cromwell routed the invading Scots at Preston (August 17), and the army put down Royalist uprisings elsewhere.

Many people held the king personally responsible for this second phase of the Civil War. The victorious army demanded that he be punished. In December, it again occupied London, and Colonel Thomas Pride removed all members of Parliament who still favored negotiations (Pride’s Purge, December 6).

Charles stood trial before a special High Court of Justice in January 1649 and was convicted of high treason against the people of England and the constitution. He was executed on Jan. 30, 1649.

Results of the war

The Commonwealth.

England then became a republic, called the Commonwealth, and the monarchy and House of Lords were abolished. But no one moved to replace the Rump of the old House of Commons, which had been reduced from more than 500 to less than 150 members. The Levellers objected to the new government but were firmly suppressed. Cromwell led the army against Ireland in 1649, finally ending the rebellion that began in 1641. His men treated the Irish with great brutality.

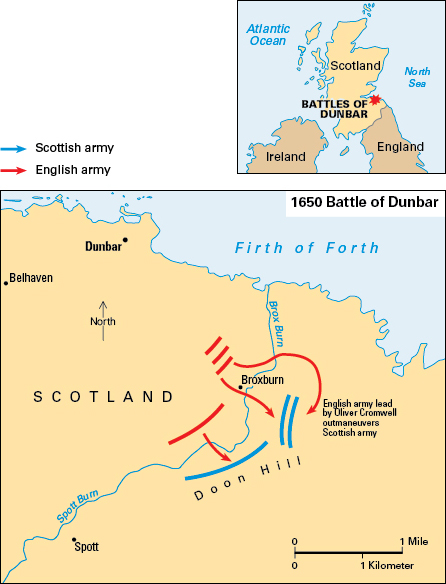

The Scots bitterly condemned the king’s execution, pointing out that he was also king of Scotland. They recognized his son as Charles II and invited him to Edinburgh. Cromwell invaded Scotland in July 1650 and defeated the Scots at Dunbar, near Edinburgh, on September 3. Montrose returned to support the young Charles, but he was defeated and executed. The next summer, Charles II himself led the last Scottish invasion of England. Cromwell defeated him at Worcester (Sept. 3, 1651). After six weeks in hiding, the king escaped to France. Scotland then came under military rule.

The Protectorate.

For all its military success, the Commonwealth could not secure the loyalty or respect of the English people. In 1653, Cromwell staged a military coup, dissolved the Rump Parliament, and ruled as Lord Protector. His son Richard succeeded him in 1658 but fell in another coup. The leaders of this revolt quarreled among themselves.

Finally, in January 1660, George Monck, a military commander, restored order. He recalled the Rump Parliament but forced it to take back the members of Parliament excluded in 1648. The Long Parliament promptly dissolved itself, calling for a general election in April. The new Parliament at once recalled Charles II from exile.

The Restoration

of the monarchy seemed to turn the clock back to 1641. Parliament restored the House of Lords and the Church of England, and established complete religious uniformity. Charles II controlled the army and appointed ministers without consulting Parliament. The divine right of kings was confirmed. But the events of the next 30 years, culminating in the Glorious Revolution of 1688-1689, showed that neither the Civil War nor the Restoration had solved the fundamental constitutional problem relating to the ultimate source of authority within the state.

See also Charles I ; Charles II ; Cromwell, Oliver .