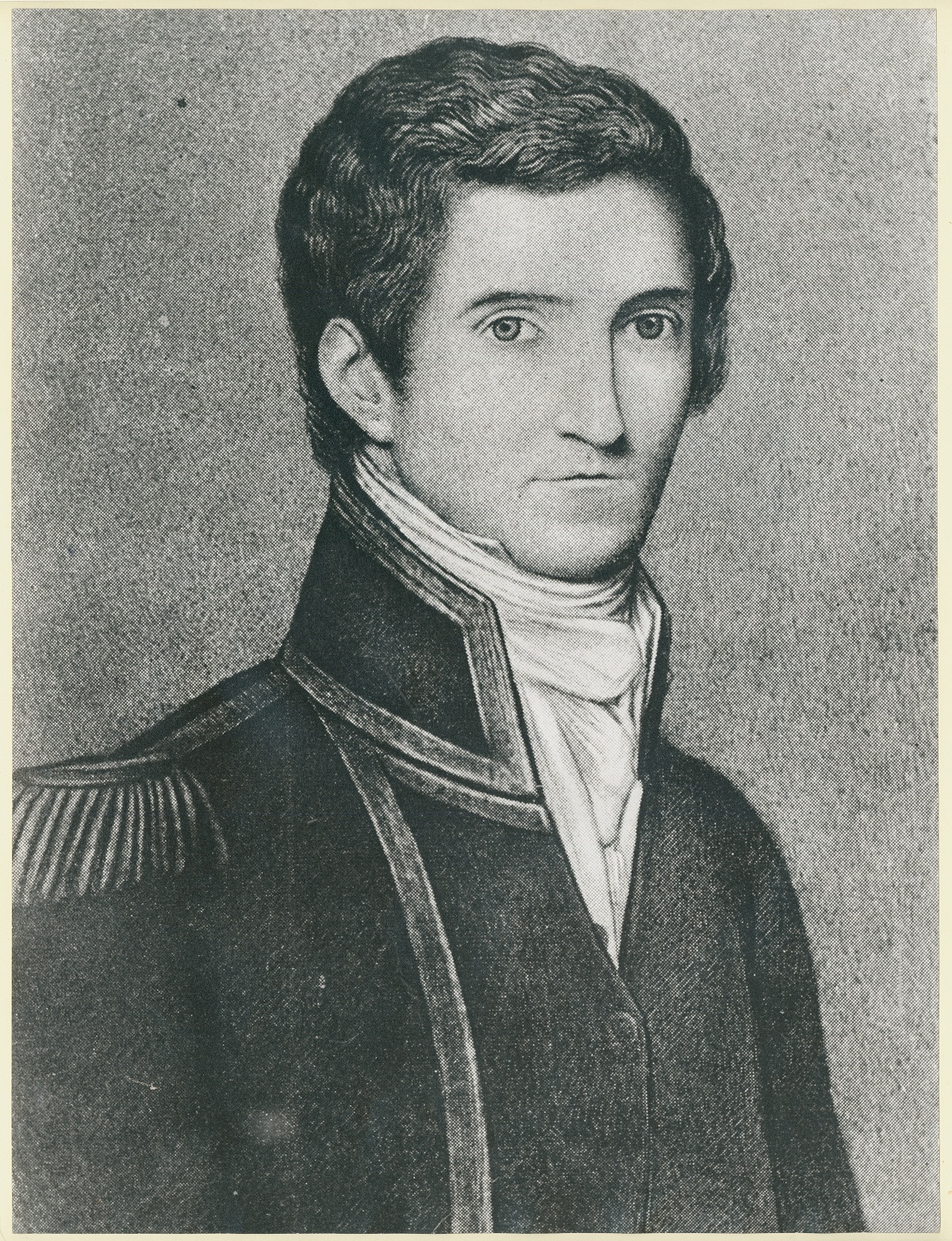

Flinders, Matthew (1774-1814), was a British navigator who charted and explored much of the coast of Australia. He was the first explorer to be credited with circumnavigating (sailing completely around) the Australian continent. With the British explorer George Bass, Flinders sailed around Van Diemen’s Land (now Tasmania) and proved that it was an island separated from the mainland by a strait. Flinders published several volumes of journals and observations from his journeys, in which he helped popularize the name Australia. At that time, the continent was often called New Holland.

Early life.

Flinders was born on March 16, 1774, in Donington, Lincolnshire, England. He joined the British navy in 1789. In 1791, he sailed to the Pacific island of Tahiti with Captain William Bligh. After returning to England, Flinders took part in the British victory over the French off Brest, France, on June 1, 1794, on board the Bellerophon. Later that year, he joined the crew of the H.M.S. Reliance as a master’s mate, an assistant to the officer responsible for navigating the ship. Flinders met Bass aboard the Reliance, which was taking John Hunter to New South Wales, Australia, to serve as the colony’s governor. Bass was a surgeon’s mate on the Reliance.

Voyages of the

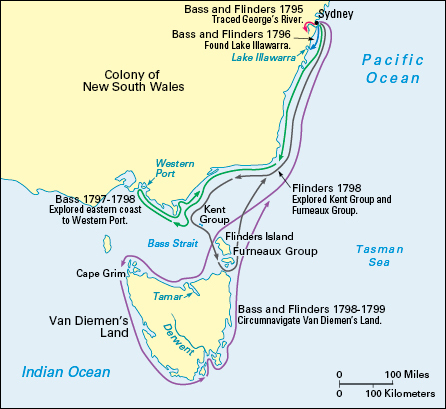

Bass and Flinders reached the settlement of Sydney in September 1795. Soon after, they set out to explore in the Tom Thumb, an 8-foot (2.4-meter) rowboat. They sailed down Australia’s eastern coast and explored Botany Bay and the George’s (now spelled Georges) River, which flows into it. In 1796, they set out in a larger boat, also called the Tom Thumb. During this expedition, they reached the expanse of water now known as Lake Illawarra.

Voyage around Van Diemen’s Land.

In early 1797, Flinders traveled to Cape Town in what is now South Africa. At the time, it was generally believed that Van Diemen’s Land was joined to the Australian mainland. While Flinders was gone, Bass explored Australia’s southern coast and came to believe that a strait separated Van Diemen’s Land from the mainland. Flinders came to the same conclusion in 1798 during a voyage to the Furneaux Islands, which lie between Tasmania and the mainland.

In October 1798, Flinders and Bass set out to test their theories in the sloop Norfolk. They passed through the strait between Van Diemen’s Land and the mainland, which, on the recommendation of Flinders, was named after Bass (see Bass Strait). They sailed around Van Diemen’s Land, completing their voyage early in 1799. They thereby proved that Van Diemen’s Land was an island.

Voyage around Australia.

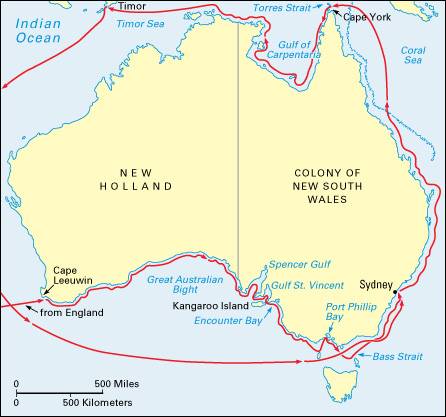

Flinders returned to England aboard the Reliance in 1800. There, he published his Observations on the Coasts of Van Diemen’s Land, on Bass’s Strait and Its Islands, and on Part of the Coasts of New South Wales. He met the naturalist Sir Joseph Banks, who helped him secure a promotion to commander. Flinders was granted command of the brig Investigator and tasked with exploring Australia’s southern coast to find out whether eastern and western Australia were separated by a large strait. On April 17, 1801, Flinders married Ann Chappell, but he had to leave her behind when he left for Australia in July.

In December 1801, the Investigator reached Cape Leeuwin, in the southwest of what is now the state of Western Australia. From there, Flinders began his voyage eastward along Australia’s southern coast. In April 1802, he met the French explorer Nicolas Baudin. Flinders named the place of their meeting Encounter Bay. Flinders continued eastward along the coast and through Bass Strait. He landed at Sydney on May 9. In Sydney, Flinders hired an Aboriginal man named Bungaree to act as a liaison (link) between his ship’s European crew and the Aboriginal groups whom Flinders expected to encounter.

After refitting his ship, Flinders sailed north on July 22. He passed the Cape York Peninsula and headed through Torres Strait, a narrow stretch of water known for its strong currents and other dangers. He then began to survey the coast of the Gulf of Carpentaria. Around this time, Flinders found that his ship was in a dangerously rotten condition. He decided to complete the journey around Australia’s coastline as quickly as possible. He reached Sydney again on June 9, 1803, and the Investigator was declared unfit to sail any farther. His voyage proved without a doubt that the Australian mainland itself was not divided by a strait. The Dutch explorer Abel Janszoon Tasman had sailed all the way around Australia in the 1640’s, but had not sighted the continent.

Voyage back to the United Kingdom.

In August 1803, Flinders set out for the United Kingdom as a passenger on the ship Porpoise. Shortly into the journey, the Porpoise was wrecked on a coral reef. Flinders returned to Sydney in an open boat and sent rescuers after the ship’s crew and passengers. He set out for the United Kingdom again on Sept. 21, 1803, in command of the schooner Cumberland. He called at Île de France, a French colony in the Indian Ocean that is now the independent nation of Mauritius. At that time, France and the United Kingdom were at war. The French governor, General Charles Decaen, suspected Flinders was a British spy and had him imprisoned. Decaen eventually allowed Flinders to live with friends on the island. In 1807, the governor received an order from the French Emperor Napoleon I (Napoleon Bonaparte) to release Flinders, but Decaen refused to obey it. During his time on Île de France, Flinders worked on his journals and other writings. He was freed in June 1810, and he finally arrived back in the United Kingdom that October.

In 1812, Flinders’s wife, Ann , gave birth to the couple’s only child, a daughter named Ann. Flinders’s grandson, William Matthew Flinders Petrie (later known as Sir Flinders Petrie), became a famous Egyptologist (expert on ancient Egypt).

Matthew Flinders spent the last years of his life writing the book A Voyage to Terra Australis. He died on July 19, 1814, the day after the book was published. In 2019, archaeologists discovered Flinders’s remains under a railway station in London, England. The remains were reburied in Lincolnshire in 2024.