Kings and queens of the United Kingdom. In the past, kings and queens had great power in the United Kingdom. Today, the duties of the British monarch (king or queen) are mainly ceremonial. However, he or she serves as a symbol of unity for the British people and is generally regarded with a high level of respect.

The role of the monarch in British politics is part of the unwritten British constitution. As a constitutional monarch, the king or queen serves as head of state. He or she reigns (holds office) with the aid and agreement of an elected Parliament. For the most part, Parliament controls the government.

Before the 1600’s, monarchs led the nobility and managed state affairs through ministers they appointed. They also formed government policy. Parliament served as a sort of advisory council rather than as a governing body. In the 1640’s, Parliament and its supporters defeated the reigning king, Charles I, in a civil war. Charles was executed in 1649, and the Commonwealth of England replaced the monarchy. Under the new government, a committee of Parliament ruled England. In 1660, the monarchy was restored. After that date, however, Parliament gradually took control of the government and the monarchy’s power declined.

Kings and queens reigned in what is now the United Kingdom long before the emergence of England, Ireland, Scotland, and Wales as separate political divisions. When the Romans first arrived in Britain in 55 B.C., powerful chiefs ruled tribes of native Britons. Between the late A.D. 300’s and the early A.D. 600’s, Anglo-Saxons conquered much of the island of Great Britain and established kingdoms there. The Anglo-Saxons were members of Germanic tribes, mostly from what are now Denmark, northern Germany, and the Netherlands. By the early 600’s, the descendants of the native Britons ruled as kings and princes only in the areas that later became known as Cornwall, Wales, and part of Scotland.

Most of what is now England was not united under the rule of one monarch until the late 900’s. Malcolm II, who reigned from 1005 to 1034, was the first monarch to rule what is now Scotland. In the early 1280’s, Wales came under the control of Edward I, an English king. In 1536 and 1543, during the reign of Henry VIII, Parliament passed acts that joined England and Wales. In 1603, King James VI of Scotland also became James I of England, thereby uniting the Scottish and English crowns. In 1707, the English and Scottish parliaments passed an Act of Union that established a united Kingdom of Great Britain. In 1801, another Act of Union provided for the addition of Ireland to create the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.

Early rulers

The earliest kings and queens in Britain arose many thousands of years after human beings arrived there. People did not start living in settled communities until the Neolithic (New Stone Age) Period, which began in Britain about 4000 B.C. Neolithic people built houses and farmed, and they formed organized societies. In the course of time, some tribes chose leaders, most likely the person best able to lead them into battle.

Use of the Celtic language probably spread through Britain sometime after about 500 B.C. The recorded history of Britain began when the Romans invaded the island in the 50’s B.C. By that time, the Celtic language was the primary language used. The Britons had also organized themselves into tribes with military leaders. The Roman leader Julius Caesar believed that some Britons had helped the Gauls in present-day France fight against Roman rule. Caesar also knew that any conquests he made in Britain would boost his popularity in Rome. In 55 and 54 B.C., Caesar and his Roman legions invaded southeastern Britain.

A confederation of British tribes chose Cassivellaunus << kas uh vuh LAW nuhs >> , the chieftain of a powerful tribe with lands in present-day Hertfordshire, to lead the fight against the Roman invaders. Cassivellaunus was an able soldier. He harassed the Romans with his charioteers. But Caesar defeated him and seized his main stronghold. Cassivellaunus then accepted a peace agreement.

Caesar withdrew his troops in 54 B.C. Trade grew between Rome and Britain. Many British kings prospered. Among them was Cunobelinus << kyoo nuh buh LY nuhs >> , leader of the powerful Catuvellauni << kat uh vehl LAW ny >> in southeastern Britain and possibly a descendant of Cassivellaunus. Cunobelinus was a capable ruler who profited from commerce between Rome and Britain. He ruled from about A.D. 5 or 10 until about A.D. 40.

In A.D. 43, the Roman Emperor Claudius invaded Britain. The Romans defeated the Catuvellauni. But Cunobelinus’s son Caratacus << kuh RAT uh kuhs >> went to Wales and led a resistance movement against the Romans. In 51, the Romans captured Caratacus. In 60 to 61, Boudicca << boo DIHK uh >> , also called Boadicea << boh ad ih SEE uh >> ), queen of the Iceni of eastern England, led a revolt against the Romans. Her forces captured Camulodunum << kam yuh loh DOO nuhm >> (now Colchester), Londinium << lon DIHN ee uhm >> (now London), and Verulamium << vehr yoo LAY mee uhm >> (now St. Albans) and killed many inhabitants. The Romans eventually defeated Boudicca. She escaped, but soon died, probably by taking poison.

During the Roman occupation of Britain, leaders of the Britons who submitted to Roman authority were allowed to rule as local representatives of the Roman emperor. They became Roman citizens. After Christianity became the official religion of the empire in the 300’s, many leading Britons became Christians.

During the mid-300’s, tribes of Germanic peoples, including Angles, Jutes, and Saxons, began to raid Roman Britain in large numbers. The Picts and Scots from the north also often attacked the Roman provinces. But the last of the Roman soldiers left Britain in the early 400’s to protect other parts of their declining empire from invaders. With the Romans gone, local British chiefs established themselves as rulers in the former Roman provinces. From time to time, some of these chiefs established lordship over others.

Some medieval histories tell the story of a king of Kent named Vortigern << VAWR tuh gurn >> , who became the overlord of most of Romanized Britain in the mid-400’s. According to legend, Vortigern sought aid against further raids and protection for his kingdom by hiring two Anglo-Saxon or Jutish leaders, Hengist and Horsa, to help him. He allowed these chiefs and their forces to settle in Kent. Later, Hengist and Horsa rebelled against Vortigern. Horsa was killed, but Hengist and his son Aesc (pronounced ask; also spelled Oisc) conquered and then ruled Kent.

Other foreign raiders settled in Britain, and the Anglo-Saxon raids grew into a large migration of people seeking new land. The Anglo-Saxons set up their own kingdoms in the central, eastern, and southern parts of the island. Those Britons who remained in areas dominated by the Anglo-Saxons gradually lost their separate identity and language. Independent kingdoms ruled by descendants of the ancient Britons were confined to the northern and western parts of the island, in what eventually became Cornwall, Wales, and parts of Scotland.

The Anglo-Saxon and Danish kings

The Anglo-Saxon settlement.

Beginning in the A.D. 400’s, Anglo-Saxon invaders carved large and small kingdoms out of the area they conquered. Three main kingdoms eventually developed: Northumbria in northeastern England, Mercia in the central region, and Wessex, in the south and southwest. Other smaller but significant Anglo-Saxon kingdoms included East Anglia, Essex, Kent, and Sussex.

According to tradition, Cerdic << CHEHR dihch >> , the leader of a Saxon tribe called the Gewisse, invaded southern Britain and established a kingdom in the early 500’s. The Gewisse later became known as the West Saxons, and their kingdom was called Wessex. All the kings of Wessex claimed to belong to the House of Cerdic.

The early Anglo-Saxon kings were pagans. They worshiped many gods. Most claimed to be descended from the Norse god Odin, whom the Anglo-Saxons called Woden. Ethelbert, also spelled Aethelberht, ruled Kent when the Christian missionary Saint Augustine of Canterbury arrived from Rome in 597. Ethelbert was the first Anglo-Saxon king in England to become a Christian.

Northumbria

emerged in the 600’s from the combination of Bernicia << bur NIHSH ee uh >> and Deira << DEE ruh >> , two Anglo-Saxon kingdoms. The first known ruler of both kingdoms was Ethelfrith, also spelled Aethelfryth, who became king of Bernicia in 592 and of Deira in 604. Ethelfrith also subdued the Scottish lowlands. His conquests separated the Britons of southern Scotland from those of northern Wales.

In 616, Edwin, a descendant of a Deiran king, overthrew Ethelfrith. Edwin, also spelled Eadwine, ruled Northumbria until 633. He extended his influence as overlord across parts of central and southern Britain. Conflict followed Edwin’s death, but eventually Ethelfrith’s family regained the crown. Ethelfrith’s son Oswald was king of Northumbria from 634 to 642. Oswald’s brother Oswiu << OHS wee oo >> , also called Oswy << OS wee >> , ruled from 642 to 670. Both brothers received recognition as overlord from some additional kingdoms to the south. During the late 600’s and early 700’s, Northumbria experienced a flowering of religious and literary culture known as the Northumbrian renaissance. In the 700’s, families fought violently for the kingship, but Northumbria remained powerful.

Mercia.

During the 600’s and 700’s, the kingdom of Mercia rose to prominence in the Midlands. Mercia’s first major king, Penda, was a pagan noble who helped to overthrow Edwin of Northumbria in 633. He defeated Oswald in 642. Until his defeat by Oswiu in 655, Penda was the most important king in England. Penda’s son, Wulfhere << WOOLF hehr uh >> , reigned from 658 to 675 and won recognition as overlord of southern England. Wulfhere’s successors lost the authority he had won, but his cousin’s son Ethelbald, also spelled Aethelbald, regained it. Ethelbald, who reigned from 716 to 757, became overlord of all the English kingdoms between the River Humber and the English Channel. Ethelbald was murdered in 757 and was eventually succeeded by Offa.

Offa, the greatest of the Mercian kings, reigned from 757 to 796. He was a strong king who reduced several southern kingdoms to provinces. Offa developed commerce and established diplomatic relations with Charlemagne, the ruler of what is now France and much of western Europe, and with the pope. He built a great defensive rampart, called Offa’s Dyke, to serve as a boundary between Mercia and the Welsh kingdoms.

Wessex.

After the death of Offa, the power of the Mercian kings declined. The kingdoms of East Anglia, Kent, and Wessex rebelled against Mercia. Egbert, also spelled Ecgberht, became king of Wessex in 802. In 825, he defeated a Mercian army and ended Mercia’s domination of southern England.

Egbert reigned until 839. He founded a dynasty that ruled in England for most of the next 230 years. Egbert conquered the Cornish people of southwest England. He annexed (joined) the kingdom of Kent to Wessex and even forced the Northumbrians to submit briefly to his overlordship. But by the end of his reign, Egbert’s power was much reduced. Egbert’s son, Ethelwulf, also spelled Aethelwulf, succeeded him in 839. Ethelwulf reigned until 858. An able ruler, he strengthened Wessex.

During the reigns of Egbert and Ethelwulf, southern England suffered its first large Viking raids. The Vikings, seafaring warriors from what are now Denmark, Norway, and Sweden, had begun attacking Britain in the late 700’s. Most of their early attacks occurred in Ireland and Scotland. But beginning with a large raid on Kent in 835, Danish Vikings attacked southern Britain nearly every year. In 851, Ethelwulf defeated a Danish army in southeast England. However, the raids continued.

Ethelwulf left four sons, who each succeeded in turn to the kingdom of Wessex. The most forceful of them were Ethelred I, also spelled Aethelred, and Alfred. Ethelred ruled from about 865 to 871. During his reign, a great army of Danes invaded England. They took over Northumbria, East Anglia, and part of Mercia. Ethelred and Alfred fought several battles against the Danes in 870 and 871, winning one significant victory in 871. During this time of crisis, Ethelred died.

Alfred, who succeeded Ethelred as king of Wessex, was the most famous king in early English history. People often call him Alfred the Great. He was a politician and general; a man of culture, religion, and learning; and a fine writer and translator.

In 878, Alfred decisively defeated a Danish army at the Battle of Edington. The Danish leader Guthrum agreed to a peace treaty, and the army withdrew from Wessex. Alfred freed London from Danish occupation in 886. He divided the country with the Danish settlers. The Danish part of England—the eastern and northern regions—eventually became known as the Danelaw. The non-Danish part became united under Alfred’s authority.

Alfred made many reforms and passed many laws. He reorganized his armies and started to build what some experts have seen as the first English navy. He also arranged a successful system of strongholds known as burghs (later boroughs) to defend Wessex.

Alfred’s military reforms made his position much stronger when fresh Danish invaders arrived in 892. Alfred drove the invaders back from the areas held by the English and defeated them in 896.

Alfred died in 899. He was succeeded in Wessex by his oldest son, Edward the Elder, also spelled Eadward, who reigned until 924. Alfred had laid the foundation for a united English monarchy, and Edward carried on this work. Edward was an able warrior and diplomat. His main achievement was the conquest of all the Danish settlements south of the River Humber. His sister Ethelfleda, also spelled Aethelflaeda, the wife of Mercia’s ruler, helped achieve this conquest. She continued to rule Mercia after her husband died in 911. After her death in 918, Edward ruled Mercia directly. Several Welsh princes also acknowledged Edward as their overlord.

Edward’s oldest son, Athelstan, also spelled Aethelstan, reigned from 924 to 939. Athelstan had been raised at Ethelfleda’s court in Mercia and received much support from both the Mercians and the people of Wessex. He extended his overlordship to include the Danish kingdoms of northern England and some kingdoms in Scotland, Wales, and Cornwall. Mainly through the marriages of his sisters, he came to have a number of family connections throughout Europe.

Athelstan’s successor was his brother Edmund I, also spelled Eadmund. Edmund defeated attacks by Norwegian Vikings, who had established a kingdom at York, in northern England. He also took an active part in European affairs before he was murdered in 946. Edmund’s brother Edred, also spelled Eadred, succeeded him. Edred invaded York in 948 and in 952 and ended Viking control of that region. He died childless in 955, and his brother Edmund’s son Edwig, also spelled Eadwig or Edwy, succeeded him. Edwig was about 15 at the time.

In 957, the kingdom was divided and Edwig’s brother, Edgar, became ruler of the land north of the River Thames. Edwig continued to rule the south and was probably his brother’s overlord. Edwig died in 959.

Edgar reigned over the entire kingdom from 959 to 975. He was one of the country’s greatest monarchs and became known as Edgar the Peaceful. Edgar was a great legislator and effectively reformed England’s coinage. He founded many monasteries and was guided by a group of clerics who included Saint Dunstan, the archbishop of Canterbury.

After Edgar died, his two surviving sons, Edward and Ethelred, also spelled Aethelred, were too young to rule. The English nobles formed rival parties around the boys. The nobles backing Edward gained power first. But Edward reigned for less than three years before Ethelred’s supporters assassinated him in 978. Edward’s murder angered the country. He became known as Edward the Martyr and was declared a saint.

Ethelred II succeeded Edward. During his reign, Danish raiders attacked England again. Ethelred levied taxes on his people to pay the Danes to go away or keep the peace. Although this policy preserved the kingdom, it encouraged the Danes to return for further payments. The king also instituted a new tax, later called Danegeld, that he used to pay some Danes to fight for him as mercenaries (soldiers paid to fight in a foreign army).

In 1002, Ethelred married Emma, daughter of Count Richard of Normandy. This marriage later helped to provide Duke William of Normandy with a claim to the English throne.

Danish raids intensified. Then, in 1013, King (pronounced Sweyn << svayn >> ; also spelled Swein or Sven) Forkbeard of Denmark launched a major invasion of England. He overcame Ethelred in a hard-fought campaign, and Ethelred fled to Normandy.

Danish kings in England.

The English accepted Sweyn as king late in 1013, but he died after only a few weeks. Ethelred II returned from Normandy and resumed his reign early in 1014. After Ethelred died in 1016, his son Edmund II Ironside became king. But Sweyn’s son Canute, also spelled Cnut, sought to reclaim his father’s kingdom in England. In 1016, Canute and Edmund signed a treaty dividing England between them. But Edmund died suddenly shortly afterward.

Canute ruled England alone until 1035. He succeeded his brother as king of Denmark in 1019 and acquired Norway in 1028. Canute proved himself an effective king. In England, he restored order and brought good government to the country. The weakness of Ethelred II had caused people to lose respect for the monarchy. But Canute brought the country back under firm, though sometimes ruthless, rule. He improved England’s defense and helped its traders win new markets.

Canute married Ethelred’s widow, Emma. Their son Hardecanute << har duh kuh NOOT >> , also spelled Harthacnut, was in Denmark when his father died in 1035. Because of the political situation in Denmark, Hardecanute could not return to England immediately. In 1037, the witanagemot (king’s supreme council) elected as king another son of Canute, Harold Harefoot. The nickname Harefoot meant fleet of foot. Harold’s mother, Elgifu of Northampton, also spelled Aelgifu, and an English earl, Godwine, both helped him win the throne.

After Harold died in 1040, Hardecanute finally succeeded as king of England, but he died two years later. The throne then passed to Edward, the only surviving son of Ethelred II and Emma.

Edward, later known as “the Confessor” because of his great piety, had lived in Normandy for 25 years. He was a stranger in England. Earl Godwine and his sons dominated affairs during most of Edward’s reign. Edward’s closest heirs by blood were his nephew, Edward the Atheling, and the Atheling’s young son, Edgar the Atheling. Atheling, also spelled aetheling, was an Old English word denoting a prince of royal blood. Edward the Atheling died in 1057. Many scholars believe that in 1051, King Edward might have promised some right in the succession to Duke William of Normandy.

The Norman Conquest.

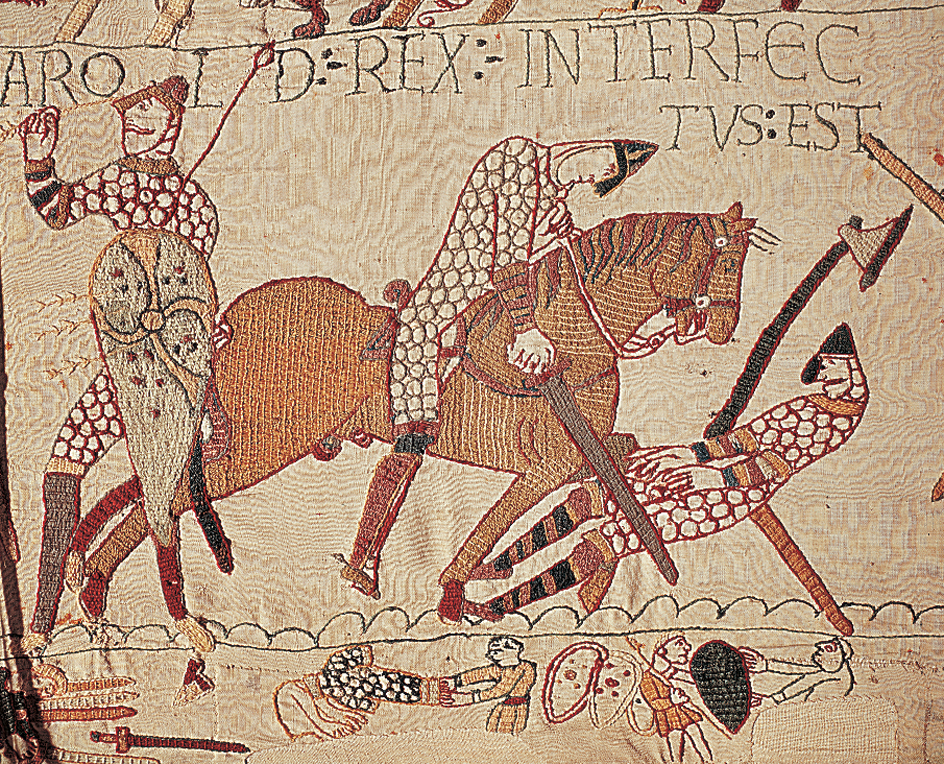

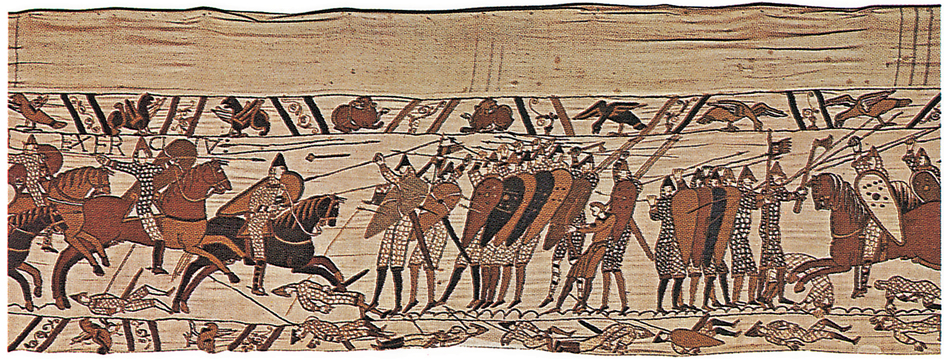

The English earls opposed the succession of William. After Edward the Atheling’s death, Edgar the Atheling was just a child. So the witanagemot chose Harold Godwineson, one of Earl Godwine’s sons, to be king. He became Harold II in January 1066. In the autumn, Harold faced two invasions. In the first, Harold’s brother Tostig accompanied a Viking invasion led by King Harald Hardrada << HAH rahl HAHR rah dah >> of Norway. In the second, Duke William came with an army from Normandy to claim the throne. On September 25, King Harold and his army defeated and killed Tostig and Harald Hardrada at the Battle of Stamford Bridge in northern England. Harold then hurried south to meet William’s forces. On October 14, in the Battle of Hastings, William and his forces defeated and killed Harold. William then seized the English throne.

Early rulers of Scotland and Wales

The Britons who kept control of independent kingdoms in northern and western Britain after the A.D. 600’s were ancestors of the Cornish, Scottish, and Welsh people. Tradition says that Cunedda << kihn EHTH uh >> , ruler of the Britons in the territory along the Firth of Forth, came to northern Wales around the late 300’s or early 400’s and drove out Irish invaders. Later, the rulers of the important kingdom of Gwynedd << GWIHN ehth >> in northwestern Wales claimed to be his descendants.

Scotland.

Little is known of early rulers of Scotland. Four groups came to occupy the land after the Romans withdrew. Each had a number of tribes and formed a number of small kingdoms. The Britons were native people in southern Scotland whose ancestors had been ruled by Rome. The Picts, in the north and east, were ancient people of northern Britain who had never been under Roman rule. The Scots came from Ireland. They occupied Argyll and the Western Isles, off Scotland’s northwest coast. And the Angles were a Germanic people who arrived as part of the larger Anglo-Saxon migration. They competed with the Britons for control of the south.

Until the 800’s, the Angles, Britons, Picts, and Scots often raided one another for silver and cattle. After about 740, Pictish kings often dominated the country. Viking raids in the early 800’s probably weakened the Picts. In the early 840’s, Kenneth I MacAlpin, a king of the Scots, united his realm with that of the Picts. Kenneth’s name is also spelled Kenneth MacAlpine or Cinaed mac Alpin.

Violent rivalries marked the early history of the Scottish kings, but they managed to extend their authority. Kenneth II, also spelled Cinaed, reigned from 971 to 995. In the 970’s, King Edgar of Wessex formally recognized Kenneth’s authority over the land between the Rivers Tweed and Forth. This region, once controlled by Northumbria, was called Lothian.

Malcolm II, also spelled Mael Coluim, emerged as the first ruler of Scotland roughly as we know it today. Malcolm became king in 1005. By about 1018, he controlled Lothian and Strathclyde. But Viking settlers continued to control Orkney, Shetland, and the Western Isles.

In 1034, Malcolm’s grandson Duncan I succeeded to the throne. He was a rash king. In 1040, Macbeth, also spelled Mac Bethad, the ruler of Moray in northern Scotland, defeated and killed Duncan in battle near Elgin. Macbeth seized the throne and proved to be an effective, strong ruler. In 1054, Duncan’s son, also named Malcolm, and Siward << SOO uhrd >> , Earl of Northumbria, defeated Macbeth in battle at Dunsinane but did not dethrone him. Macbeth held on to the throne until 1057, when Malcolm’s forces killed him at Lumphanan << luhm PAH nuhn >> , near Aberdeen, Scotland. After a brief campaign against Macbeth’s stepson, Lulach, Malcolm became King Malcolm III of Scotland in 1058.

Malcolm III, known as Malcolm Canmore, was a strong ruler. His name is also spelled Mael Coluim caenn mor. He founded a dynasty that lasted nearly 250 years. Under Malcolm, Scotland accepted some English influences. Malcolm married Margaret, the granddaughter of the English King Edmund Ironside. Known for her Christian piety, she helped introduce reforms in the Scottish church that were similar to those being carried out elsewhere in Europe. She was later declared a saint.

Wales.

After the Romans left Britain in the 400’s, many independent kingdoms developed in Wales. Four major kingdoms eventually emerged: Gwynedd in the northwest; Powys << POH ihs >> in central Wales; Dyfed << DUH vehd >> , which later became part of Deheubarth << duh HAY barth >> , in the southwest; and Gwent, which later became part of Morgannwg << mawr GAHN uhg >> , in the southeast.

In the mid-500’s, one of the strongest rulers in Wales was Maelgwn Gwynedd << MAYL goon GWIHN ehth >> , king of Gwynedd. Tradition says that Maelgwn was a ruthless, wicked ruler. But he was also a man of culture, and many poets and musicians attended his court at Deganwy. In 633, Cadwallon, king of Gwynedd, helped Penda of Mercia overthrow King Edwin of Northumbria. In 634, Cadwallon died in battle against Oswald, Edwin’s eventual successor. A later ruler of Gwynedd, Cadafael ap Cynfedw << kah DAH fayl ahp koon VEHD oo >> , marched with Penda against Oswiu of Northumbria in 655. Oswiu’s force defeated that of Cadafael ap Cynfedw and Penda at the Battle of River Winwaed, near Leeds.

In the 700’s, the building of Offa’s Dyke defined the border between the Welsh and English. Separate independent kingdoms continued in Wales. The strongest kingdom was still Gwynedd.

By 825, Merfyn Frych << mur VIHN frihk >> , also called Merfyn the Freckled, had become ruler of Gwynedd. Merfyn was a firm ruler. He married the sister of Cyngen ap Cadell, the king of Powys. In 844, Merfyn’s son Rhodri Mawr << ROHD ree mawr >> , or Rhodri the Great, succeeded him. Rhodri probably became king of Powys, too, after Cyngen died in 855. He was the first Welsh ruler to unite a large part of Wales. Rhodri spent much of his reign defending Wales from Viking attacks.

After Rhodri’s death in 878, the Welsh kingdoms gradually came under the overlordship of the Anglo-Saxon kings of England. In 918, several Welsh princes paid homage to Edward the Elder of Wessex. One of these princes was Hywel Dda << HEH wehl thah >> , or Hywel the Good, a grandson of Rhodri Mawr.

Between 904 and about 930, Hywel became ruler of Dyfed and several other small kingdoms in southern Wales. He sought close links with the court of Wessex. The king of Gwynedd died in 942, while fighting the English. Hywel then extended his rule over Gwynedd and other parts of northern and central Wales. He is most famous for the codification (writing down) of Welsh laws that took place during his reign. He died in 949 or 950.

Following Hywel’s death, Wales fell back into disunity. In 986, after a period of war between the Welsh princes, ( Maredudd ab Owain << muh REHD uhth ahp OH wayn >> ), who was Hywel’s grandson and the son of the ruler of Deheubarth, conquered Gwynedd. Maredudd inherited Deheubarth after his father died in 988, and he temporarily reunited most of Wales.

The greatest Welsh ruler to consolidate the Welsh kingdoms was Gruffydd ap Llywelyn << GRIHF ihth ahp hluh WEHL ihn >> , a descendant of Hywel Dda and Rhodri Mawr. Gruffydd seized the throne of Gwynedd in 1039. Also in 1039, he inflicted a crushing defeat on the Mercians at Rhyd-y-Groes << reed ee groys >> ), near Welshpool, in Powys. It was the first of many successful Welsh raids on the English borderlands in which Gruffydd made territorial gains for his kingdom. Gruffydd also formed alliances with the enemies of King Edward the Confessor.

Within Wales, Gruffydd fought a long campaign against rival kings to win total control of the country. By 1055, he had become master of Deheubarth and extended his authority to the lesser kingdoms of Morgannwg, also called Glamorgan, and Gwent. In 1063, Earl Harold Godwineson (later Harold II of England) and his brother Tostig made a joint attack on Gwynedd. At the same time, Deheubarth rebelled against Gruffydd’s rule. Gruffydd fled, and his own countrymen murdered him.

The Normans

Two months after the Battle of Hastings, William I was crowned king in Westminster Abbey in London. The service took place on Christmas Day 1066, with the traditional ceremonies associated with the coronation of English kings since the time of Edgar. William had secured the throne by conquest, and he later became known as “the Conqueror.” But by accepting the English form of coronation, William emphasized his claim to be the rightful successor to Edward the Confessor.

William I

was a powerful king and a man of immense determination. William dispossessed nearly all the Anglo-Saxon nobles of their lands and put Normans in their places. In return, the Norman lords owed him military and other services. The Normans discouraged rebellion by building strong castles throughout the country.

William and his Norman successors imposed heavy taxes on their subjects. In late 1085, William ordered a land survey for tax purposes. A document that became known as the Domesday Book records the results of the survey. William kept tight control of political power, but his policies also brought peace and order.

In 1087, William’s second oldest surviving son, William II, succeeded him in England. William II was a short, stout man with a red face. His nickname, “Rufus,” means red. A powerful king like his father, William II ruled his subjects firmly. In 1088 and 1095, he crushed revolts by some of his barons. William obtained control of Normandy from his older brother Robert by lending Robert the money to go on a crusade, a military expedition to the Holy Land. To raise funds for the crusade, William taxed his English subjects heavily and exploited (took advantage of) the Roman Catholic Church.

William died in 1100 while hunting in southern England. An arrow that was probably shot by one of his lords, Walter Tirel, killed him. Most historians believe the shooting was an accident. William’s younger brother, Henry, succeeded to the throne.

Henry I

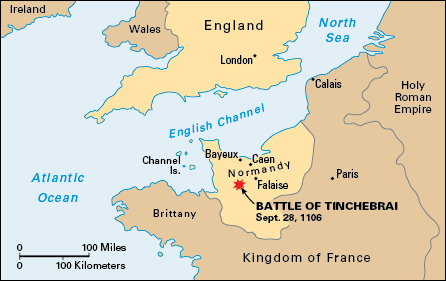

was an ambitious, unscrupulous politician and an effective king. He improved the government’s organization and the administration of justice. In 1101, Duke Robert of Normandy invaded England to claim the throne as the oldest of William the Conqueror’s sons. Henry and Robert agreed that Robert would renounce his claim in return for a pension (regular payment). In 1106, Henry invaded Normandy and defeated Robert at the Battle of Tinchebrai << tehnzh BRAY >> , in what is now northwestern France. Robert died in prison in 1134.

In November 1100, Henry had married Matilda, daughter of King Malcolm III of Scotland. Matilda’s mother, Queen Margaret, was the granddaughter of King Edmund Ironside of England. Therefore, Henry and Matilda’s descendants, including the present royal family of the United Kingdom, have traced their ancestry back to England’s Norman and Anglo-Saxon rulers.

Henry I had two legitimate children, William and Matilda, also called Maud. William drowned in 1120 while crossing from Normandy to England in a vessel called the White Ship. In 1114, at the age of 11, Matilda married the Holy Roman Emperor Henry V, who died in 1125. In 1127, Henry had his barons swear to recognize Matilda as his heir. The next year, Matilda married Geoffrey, Count of Anjou, in what is now France. Two other claimants to the throne were Henry’s nephews, (pronounced Theobald << THEE uh bawld or TIHB uhld >> and also spelled Thibaud) and Stephen. Their father was the count of Blois, also in what is now France. Their mother, Adela, was William the Conqueror’s daughter.

Henry died in 1135. When Stephen heard of his uncle’s death, he crossed to England from France and was crowned king. Theobald accepted his brother’s success, but Matilda would not give up her claim. In 1141, her supporters defeated Stephen in the Battle of Lincoln and took him prisoner. A church council at Winchester deposed Stephen and elected Matilda as ruler of England. But Matilda’s arrogance made her unpopular, and the people of London threw her out of the city before she could be crowned. Before the end of the year, some barons who favored Stephen had captured Matilda’s chief supporter, Robert of Gloucester. Matilda released Stephen from prison in exchange for Gloucester’s freedom. England remained divided, but most barons supported Stephen. In 1148, Matilda left England for good.

Stephen reigned until 1154. He proved to be an able, brave, and chivalrous king who depended heavily on the support of his barons.

Between 1141 and 1144, Matilda’s husband, Geoffrey of Anjou, seized Normandy. In 1150, he turned over control of the duchy to his and Matilda’s son Henry of Anjou. After Geoffrey died in 1151, Henry inherited the French counties of Anjou, Maine, and Touraine. In 1153, Stephen, who was childless, promised that Henry would also succeed to the throne of England.

The early Plantagenets

The counts of Anjou, known as Angevins, had built up a strong domain in France through conquests and marriages. Geoffrey, Count of Anjou and the husband of Matilda, extended his possessions by conquering Normandy. His descendants later became known by the name Plantagenet << plan TAJ uh niht >> because, according to legend, his symbol was a sprig of the broom plant (planta genista in Latin, and plante genet in French).

Henry II.

When Geoffrey and Matilda’s son Henry succeeded as King Henry II of England in 1154, he already ruled over much of western France. Henry had received Anjou, Maine, Normandy, and Touraine from his father, who had died in 1151. In 1152, he gained control of Aquitaine when he married Eleanor of Aquitaine, the divorced wife of the French King Louis VII. Henry’s succession to the throne of England made him more powerful than his overlord, the king of France. In 1166, Henry brought Brittany under his control. In 1172, he extended his realm even farther by becoming overlord of Ireland. This vast empire needed all of Henry’s decisiveness and energy for its preservation.

The Norman kings had created powerful barons in England. These barons had become unruly during Stephen’s reign, but Henry disciplined them and reformed the law and government of England. He developed a judicial system that included juries and traveling judges. He also increased the importance of the English exchequer (treasury). In addition, Henry raised taxes and changed the traditional obligations of the military. These changes increased the monarch’s power over the English military and decreased the barons’ influence.

In 1170, four of Henry’s knights, believing they were carrying out Henry’s wishes, murdered Thomas Becket, the archbishop of Canterbury and Henry’s former friend. The murder occurred while Henry was seeking to reduce the power of the church courts, which had become increasingly independent of the royal authority. However, after Becket’s death, Henry abandoned his plans and did penance for the crime.

Henry spent much of his life working to preserve his French possessions. He gave the government of some of these lands to three of his sons—Henry, Richard, and Geoffrey. John, the youngest son, who originally had no territories to rule, received the nickname “Lackland.” All four sons rebelled against Henry at one time or another.

Richard I.

Henry died in 1189, leaving the throne to his oldest surviving son, who became Richard I. Richard was known as Coeur de Lion (the Lion-Hearted) due to his courage. He spent most of his reign outside England. From 1190 to 1192, he took part in a crusade to the Holy Land to try to recover various religious sites, particularly Jerusalem, that were important to Christians but held by Muslims. In December 1192, while returning from the Holy Land, Richard was imprisoned by Duke Leopold of Austria and the Holy Roman Emperor Henry VI. England had to pay a huge ransom to free the king. Richard returned to England briefly in 1194 and then spent the rest of his reign fighting in France to regain possessions the French king had seized while Richard was imprisoned. The cost of the crusade, the ransom, and the wars in France strained the resources of all the Angevin lands, including England. Richard died after being wounded at the Siege of Chalus << shah LOO >> , in Aquitaine, in 1199.

John.

The monarchy weakened during the reign of Richard’s youngest brother, John. Richard had chosen John as his heir. But Philip II of France, John’s overlord for his French territories, supported the claim of Arthur, the son of John’s older brother Geoffrey. War broke out between Philip and John in 1202, and John captured the 15-year-old Arthur at the Battle of Mirabeau in France and imprisoned him. Arthur disappeared mysteriously in 1203, and many people accused John of his murder.

As king, John was a failure. He administered justice unpredictably and had little regard for his subjects’ traditional rights. His defeats in war led to the loss of Normandy and other Angevin possessions. The wars also placed a heavy financial burden on England, and many of John’s barons grew discontented.

In 1207, John and Pope Innocent III disagreed over whose right it was to appoint the archbishop of Canterbury. In 1208, the pope placed England under an interdict, an order banning church services. He excommunicated John in 1209. John made peace with the pope in 1213, and the pope supported John thereafter.

In 1215, John’s barons forced him to approve a document called Magna Carta (the Great Charter). The charter limited the king’s powers and defined the rights of the barons and freemen.

Henry III.

The struggle between barons and the king continued into the reign of John’s son, Henry III. Henry was only 9 years old when he became king in 1216. During his childhood, a small group of barons governed. Henry officially began his reign in 1227, but he did not actually take control of the government until 1234.

As king, Henry angered English barons by collecting high taxes, waging war unsuccessfully in France and Wales, planning a costly invasion of Sicily, and accumulating large debts. He entrusted his family and foreign advisers to carry out government business and disregarded other talented leaders in England. High inflation added to Henry’s financial woes.

At the time of Henry’s reign, great political change was afoot in England. The idea was growing that there should be an accepted system of laws—what later became known as common law—for the whole country, and regular methods of political cooperation between the king and barons. The king’s Great Council, a group of nobles and high-ranking clergy who advised the king, gradually gained influence. It eventually developed into the governing body known as Parliament.

Civil war broke out in 1264 when many barons, led by Simon de Montfort, united to curb Henry’s power. In 1265, Henry’s son Edward defeated Simon. Henry died in 1272, and Edward succeeded him.

Edward I

was one of the greatest of the Plantagenet kings. He was practical and worked well with the English barons. Edward conquered Wales and fought to bring Scotland under English rule. He kept peace with France for most of his reign but became involved in a costly war there in the mid-1290’s. Edward’s need for military funds led him to call frequent meetings of Parliament throughout his reign. In return for money grants from Parliament, he agreed that certain taxes could be levied only with Parliament’s consent. He died in 1307.

Rulers of Scotland, 1093-1371

After Malcolm III died in 1093, his brother Donald III, also spelled Domnal, seized the Scottish throne. Donald disliked the English influence introduced by Malcolm and expelled all the English nobles from the court. With help from the English King William II, Malcolm’s son Duncan II ousted Donald in 1094. But Duncan was killed later that year and Donald reclaimed the throne. In 1097, Edgar, another son of Malcolm, defeated and captured Donald in battle, again with English aid. Edgar reigned until 1107 and accepted William II of England as his overlord.

Generally peaceful and friendly relations with England continued during the reigns of Edgar’s brothers, Alexander I and David I. David, who reigned from 1124 to 1153, was open to new ideas. He supported church reforms and founded trading towns. David developed a new administrative system with local justices and sheriffs. He also established Norman feudalism in Scotland. However, David upheld ancient Scottish laws and opposed English claims to authority in Scotland. He also acquired English territory in Cumbria and Northumbria.

David’s grandsons, who succeeded him, lost much of what he had won. Malcolm IV was just 12 years old when he became king in 1153. Henry II forced him to return Scotland’s English territories in 1157. Malcolm’s brother, William, succeeded him in 1165 and tried to regain the territories. However, the English captured William and forced him to acknowledge Henry as his overlord. William improved the royal law courts, and one medieval writer called him a “lion of justice.” This may be why later historians called him William the Lion. He reigned for 49 years—from 1165 to 1214.

William’s son and grandson, Alexander II and Alexander III, had fairly peaceful and prosperous reigns. Both kings married English princesses. They maintained peace with England during most of their reigns and brought the Scottish nobility more firmly under royal control. These accomplishments allowed them to turn their attention to the goal of expanding Scottish power in the northwest. In a treaty in 1266, Norway agreed to turn over the Western Isles to Alexander III.

When Alexander III died in 1286, there were no more direct male heirs from the House of Malcolm Canmore. Alexander’s only descendant was Margaret, his 3-year-old granddaughter. Margaret was called “the Maid of Norway” because her mother, the daughter of Alexander III, had been queen of Norway. Regents ruled on Margaret’s behalf for four years. Then, Margaret died in 1290, plunging Scotland into a crisis. Thirteen people claimed the throne, including John Balliol << BAYL yuhl >> and Robert Bruce, Lord of Annandale. Balliol and Bruce were descendants of different great-granddaughters of David I. The claimants all agreed to let Edward I of England judge the case, and he chose John Balliol as king.

Edward tried to use John Balliol to control Scotland. He insisted on exercising his feudal rights in Scotland, for example by overturning decisions made in John’s own court and calling on Scottish troops to fight in an English war against France. Eventually, John and the Scots rebelled. Edward defeated John at the Battle of Dunbar in 1296, and John surrendered a few months later. Edward forced John to abdicate and declared himself king of Scotland. The Scots soon renewed the rebellion against English rule. They won several victories under the leadership of Sir William Wallace, a Scottish knight. But Edward gradually overcame the resistance. By 1304, he had forced or persuaded most of the Scottish nobles to submit to him. The English captured and executed Wallace in 1305.

The Scots soon found a fresh leader in Robert Bruce, the grandson of John Balliol’s chief rival for the throne. Bruce was noble, kindly, and a tireless fighter. He rallied his people against the English. In 1306, he had himself crowned King Robert I of Scotland. Robert recaptured castles in Scotland and raided northern England. In 1314, Edward II, Edward I’s son, led an English army into Scotland. Robert defeated him at the Battle of Bannockburn. In 1328, in the Treaty of Edinburgh, also called the Treaty of Northampton, the English recognized Scottish independence. They agreed that Robert’s son, David, should marry Joan, the sister of Edward III of England.

When Robert I died in 1329, his son, David II, was only 5 years old. Edward III formed an alliance with Edward Balliol, the son of John Balliol, to defeat David’s guardians. Edward Balliol gained the throne in 1332. David’s supporters sent the boy to France for safety in 1334 and fought against Edward’s rule. They finally gained enough strength for David to return and rule in 1341. But while raiding England in 1346, David was defeated and captured at Neville’s Cross, near Durham. Edward released him 11 years later for a large ransom. David died childless in 1371.

The last rulers of Wales

Disunity among the Welsh kingdoms followed the death of Gruffydd ap Llywelyn in 1063. The Norman barons of William I took advantage of the disunity to gain territory in Wales. They built strong castles in the Welsh Marches (border districts) and ruled parts of Wales as lords. Norman families who rose to power in Wales included the Clare and Montgomery families.

Native Welsh princes resisted the Norman barons and continued to hold the ancient kingdoms of Deheubarth, Gwynedd, and Powys. In 1093, Rhys ap Tewdwr << rees ahp TEH door >> , the ruler of Deheubarth, died while fighting the Normans. In 1094, Cadwgan ap Bleddyn << kah DOO guhn ap BLEHTH ihn >> , ruler of Powys, participated in a widespread Welsh rebellion against William II, the English king. However, Cadwgan later recognized William II and Henry I as his overlords. Fighting among his relatives disrupted the later years of Cadwgan’s rule. His nephew Madog << MAH dawg >> murdered him in 1111.

The most effective Welsh ruler of the late 1000’s and early 1100’s was ( Gruffydd ap Cynan << GRIHF ihth ahp KOON uhn >> ). Throughout his reign, he showed great statesmanship. Gruffydd’s father was the exiled son of a former king of Gwynedd, and his mother was the daughter of the Viking king of Dublin, in Ireland. Gruffydd was born in Ireland. He went to Wales in 1075 to try to regain the throne of Gwynedd. He helped Rhys ap Tewdwr overcome rival princes. In 1081, Gruffydd took control of Gwynedd. But Baron Robert of Rhuddlan << RIHTH lahn >> captured and imprisoned him for several years. In 1094, Gruffydd joined the Welsh revolt against the Normans. He regained firm control of Gwynedd by 1099. Gruffydd eventually ruled northern Wales as far east as the River Clwyd << KLEW ihd >> . In 1114, faced with an invasion by Henry I, he recognized Henry as his overlord. Gruffydd died in 1137.

The two chief Welsh rulers of the 1100’s were Owain Gwynedd << OH wihn GWIHN ehth >> and Rhys ap Gruffydd << rees ahp GRIHF ihth >> . Owain Gwynedd became ruler of Gwynedd on the death of his father, Gruffydd ap Cynan, in 1137. Owain proved himself a brilliant general and politician. While Matilda and Stephen, the daughter and nephew of Henry I, fought over the English throne, Owain took advantage of the chaos in England to expand Gwynedd’s territory to the northeast.

In 1154, Henry II, Matilda’s son, gained firm control of England. Henry invaded Wales in 1157 to regain the lands England had lost. Owain avoided a confrontation by acknowledging Henry as overlord. However, Owain soon resumed his policy of expansion and participated in other revolts during the early 1160’s. He won territory as far east as the mouth of the River Dee. He was the most powerful ruler in Wales from about 1165 until his death in 1170.

Rulers in other parts of Wales had also tried to take advantage of England’s weakness under King Stephen. In Deheubarth, Rhys ap Gruffydd and his three older brothers worked and fought together to expand their territory. Rhys became sole heir to these lands in 1155. Henry II soon forced Rhys to give up some of the lands and acknowledge him as overlord. But Rhys rebelled several times.

After the death of Owain Gwynedd, Rhys was the most powerful ruler in Wales. Henry, who had become worried about the growing power of the English lords in the Welsh Marches and in Ireland, allied with Rhys in 1171. He gave Rhys authority over justice in all of southern Wales. Rhys became known as Yr Arglwydd Rhys << uhr AHRL wood rees >> , or The Lord Rhys. But after Henry II died in 1189, Rhys would not acknowledge Henry’s successor, Richard I, as overlord and resumed his raids on English land. Rhys died in 1197.

Following the death of Owain Gwynedd in 1070, Owain’s son (pronounced Dafydd << DAH vihth >> and also spelled David) seized control of Gwynedd. Dafydd divided his lands with Rhodri, one of his many brothers. ( Llywelyn ap Iorwerth << hluh WEHL ihn ahp YAWR wurth >> , the son of Dafydd’s half-brother Iorwerth, drove Dafydd from power and took over eastern Gwynedd in 1194. By 1203, Llywelyn ruled all of Gwynedd. Like his grandfather Owain, Llywelyn proved a fine politician and a capable soldier. His actions earned him the name Llywelyn Fawr (Llywelyn the Great).

Llywelyn recognized King John as his overlord in 1199 and married John’s illegitimate daughter, Joan, in 1205. With John’s support, Llywelyn extended his authority into southern Wales. John became alarmed with Llywelyn’s growing power and attacked Gwynedd in 1211. Llywelyn allied himself with the English barons who rebelled against John and forced him to put his seal on Magna Carta in 1215. Through wars and alliances, Llywelyn increased the territory under his direct rule and many Welsh rulers swore allegiance to him. He eventually brought most of Wales under his control.

After John’s death, the government of young Henry III accepted Llywelyn’s authority in Wales. In return, Llywelyn paid homage to Henry as overlord. Llywelyn lived in peace with England for most of his remaining reign. After he died in 1240, his son Dafydd II succeeded him. Dafydd died in 1246.

For several years, two of Dafydd’s nephews ruled Gwynedd jointly. They were Owain Goch << OH wayn gok >> , or Owen the Red, and Llywelyn ap Gruffydd << hluh WEHL ihn ahp GRIHF ihth >> , also known as Llywelyn the Last. In 1247, Owain and Llywelyn recognized Henry III as their lord. In 1254, Owain and Dafydd, another brother, attacked Llywelyn. Llywelyn defeated them in 1255 and then ruled Gwynedd alone.

During the unrest and civil war in England during the 1250’s and 1260’s, Llywelyn sided with the English barons against King Henry III. He took advantage of England’s weakness to expand his authority in Wales. In 1258, Llywelyn began using the title Prince of Wales. Although Henry defeated the English barons, he lacked the strength to challenge Llywelyn. In 1267, Henry III recognized Llywelyn’s right to the hereditary title of Prince of Wales and his authority over the other native Welsh nobles. In return, Llywelyn swore to recognize Henry as his king.

After Henry’s death in 1272, Llywelyn refused to recognize the new king, Edward I, as his overlord. In 1277, Edward invaded Wales. He forced Llywelyn to give up much of his territory but allowed him to keep his title. In 1282, Llywelyn’s brother Dafydd started a revolt. Llywelyn became its leader. He died in a skirmish at Cilmeri << kihl MEHR ee >> , near Builth << bihlth >> , in the present-day county of Powys.

Welsh independence died with Llywelyn ap Gruffydd. Edward reportedly promised Wales a prince “who spoke no word of English,” and so he gave them his infant son, the future Edward II. Since then, reigning English monarchs have usually given their oldest sons the title Prince of Wales.

The later Plantagenets

Edward I had maintained the power of the Plantagenets. He successfully taxed property and trade to help fund his assertive policies. However, chaos broke out during the reign of Edward II, who succeeded his father in 1307. The English barons had resented Edward I’s firm rule and administrative reforms. As a result, they sought to curb the power of his son.

Edward II gave estates and other lavish gifts to his friends and let himself be influenced by greedy and ambitious advisers who were unpopular with his barons. In addition, his armies failed to stop the Scots from reasserting their independence. His forces lost the battles of Bannockburn in 1314 and Berwick in 1319.

Edward’s wife, Queen Isabella, started a rebellion against him in 1326. The English barons supported her and captured the king. In 1327, Edward was forced to abdicate (give up) the throne to his son Edward III. He was imprisoned and later murdered.

Edward III was adventurous, charming, and popular. From 1337 on, much of his reign was devoted to fighting the Hundred Years’ War in France. The “war” was actually a series of wars with France that lasted until 1453. Edward’s armies defeated the French at the battles of Crecy << kray see >> in 1346 and Poitiers << pwah TYAY >> in 1356.

The enormous expense of war made it necessary for Edward to ask his nobles for taxes, and the nobility and Parliament gained influence based on their financial contributions. Among the nobles were Edward’s sons—his heir, Edward, known as the Black Prince; and John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster. Toward the end of his reign, Edward lost his firm control of the government, and the Black Prince and the nobles competed for dominance. The Black Prince died in 1376, and his son Richard succeeded Edward III in 1377.

Richard II ascended the throne at the age of 10. During the first four years of his reign, a council ruled England on his behalf, and Richard’s uncle John of Gaunt exercised much influence. In the late 1380’s, Richard tried to increase his control over the government, which brought him into conflict with Parliament. During the 1390’s, Richard became increasingly tyrannical and angered the English people with such measures as forced loans and loyalty oaths. He tried to kill or outlaw his more dangerous opponents and made an enemy of Henry of Bolingbroke, a son of John of Gaunt. In 1399, Henry, whom Richard had exiled for treason the previous year, invaded England, deposed Richard, and became King Henry IV. Richard died in 1400. He was probably murdered.

Lancaster and York

When Henry IV seized the throne, the House of Lancaster became England’s ruling family. The house took its name from Henry’s father, John of Gaunt, who was Duke of Lancaster. Many people questioned Henry’s claim to the crown. They argued that the descendants of John of Gaunt’s older brother, Lionel, Duke of Clarence, had a better claim. Later, a descendant of John of Gaunt’s younger brother, Edmund, Duke of York, married an heiress who was descended from Lionel. From the children of this marriage came the House of York, members of which claimed the throne in the mid-1400’s.

The rule of Lancaster.

Several rebellions marked the early years of Henry IV’s reign. But Henry’s personal qualities helped him pass on the monarchy, intact, to his son. Henry was a clever, practical, and unscrupulous king. He died in 1413, exhausted, after only 14 years on the throne.

Henry V devoted his short reign to reviving the Hundred Years’ War against France. He also attempted to suppress the Lollards, a religious group whose members did not agree with some of the accepted teachings of the Roman Catholic Church. Henry defeated the French at Agincourt in 1415 and at Rouen in 1419. In 1420, he signed a treaty with the French at Troyes. The treaty provided for Henry’s marriage to Catherine, the daughter of Charles VI of France. After Charles’s death, according to the treaty, Henry would become king of France as well as of England. But Charles’s son, later Charles VII of France, refused to give up his right to the throne. Henry V died in 1422, still defending his French inheritance. His 9-month-old son, Henry VI, inherited the English throne and the right to succeed the king of France. Charles VII died one month later.

The Wars of the Roses.

As he grew up, Henry VI proved to be a weak and ineffective king. In 1445, he married Margaret of Anjou, a strong-minded French heiress who completely dominated him. For many years they had no children, and the chief claimant to the succession was Richard, Duke of York, a descendant of Edward III.

Henry conducted the Hundred Years’ War badly. His ministers were corrupt, greedy, and wasteful. In 1450, Jack Cade led a group of people from Kent in a rebellion against Henry. In 1453, the forces that Henry had sent to southern France suffered serious defeat, marking the end of the Hundred Years’ War. England lost all its possessions in France except for the port of Calais.

Henry’s nobles felt bitter and humiliated. In addition, the end of the war left many soldiers unemployed and ready to fight for anyone who would pay them. These conditions, as well as conflicting claims to the throne, eventually led to the series of civil disturbances called the Wars of the Roses. Each side that fought in the wars had a rose as its emblem. A white rose represented the House of York, and a red rose represented the House of Lancaster.

In 1453, Henry suffered a mental breakdown. That same year, his wife, Queen Margaret, gave birth to a son, Edward. The barons made Richard of York protector (ruler) of the country during Henry’s illness. Early in 1455, Henry recovered his sanity. Some nobles supported Henry and Margaret, but others supported Richard. In May, the Battle of St. Albans, the first battle of the Wars of the Roses, was fought near London.

By 1460, Henry VI had been forced to recognize Richard as his heir. But Margaret and other Lancastrians determined to continue the struggle. On Dec. 30, 1460, Lancastrian forces defeated and killed Richard of York in a battle at Wakefield, in West Yorkshire.

The rule of York.

Richard of York’s claim to the succession was taken up by his son Edward, Earl of March. Edward received help from Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick, a powerful baron later known as “the kingmaker.” In February 1461, the Earl of March entered London and assumed the title of King Edward IV. On March 29, he decisively defeated the Lancastrians at the Battle of Towton, in North Yorkshire. Henry fled the country.

Edward married an Englishwoman, Elizabeth Woodville, against the wishes of Warwick. Warwick had helped Edward gain power and wanted him to marry a French princess for diplomatic reasons. Edward granted lands and offices to members of the large Woodville family. Warwick resented his loss of influence. He deposed Edward in 1470 and once again made Henry VI king. Edward fled the country but returned with an army the following year. He seized London and captured Henry VI in early April. A few days later, Edward and his forces defeated and killed Warwick in the Battle of Barnet. In May, they defeated and killed Henry’s son, Prince Edward, at the Battle of Tewkesbury, in Gloucestershire. Less than two weeks later, Henry VI died in the Tower of London, where he had been imprisoned. Edward probably had Henry murdered.

Edward reigned until 1483. He reestablished law and order in the kingdom, improved royal finances, and encouraged international trade. His son, also named Edward, succeeded him.

Edward V was only 12 when he inherited the throne. His uncle Richard, Duke of Gloucester, controlled the government as lord protector. Richard never allowed Edward to reign. He imprisoned Edward and his younger brother Richard in the Tower of London and probably ordered their murders. Richard also arrested and executed some of the powerful relatives of Queen Elizabeth Woodville, the wife of Edward IV and mother of Edward V. He told Parliament that Elizabeth’s marriage to Edward was not valid, and that Edward V and his brother were illegitimate. In 1483, Parliament recognized Richard as king.

Richard III is one of the most controversial figures in British history. Richard was brave, generous, and intelligent. He was an able administrator and soldier. But he was also rash, insecure, and greedy. Richard’s dishonest seizure of the throne aroused opposition. Henry Tudor, Earl of Richmond, led this opposition. He was a kinsman of the House of Lancaster. His mother was a descendant of John of Gaunt. His father, Edmund Tudor, was the son of Owen Tudor. Owen Tudor came from an ancient Welsh family and had married Henry V’s widow, Catherine of France. Henry, who had been living in exile in France, landed in Wales with an army in 1485. He and his army defeated and killed Richard at the Battle of Bosworth Field, in Leicestershire. He then became King Henry VII.

The Tudors

Henry VII.

Although his claim to the crown was based on his Lancastrian ancestry, Henry VII brought a new royal house—the Tudors—to the English monarchy. Henry’s claim was questionable. Many questioned whether the branch of the family to which his mother, Margaret Beaufort, belonged should be considered legitimate descendants of John of Gaunt. But even if Henry was not the rightful heir, his victory against Richard at Bosworth Field made him king in fact. Henry was a strong ruler and reigned until 1509.

After seizing power in 1485, Henry tried to settle the conflict between Lancaster and York by marrying Edward IV’s daughter, Elizabeth of York. But there were still people with better claims to the throne than Henry’s. He had to suppress several rebellions, led by impostors who claimed the throne, during his early years as king.

Henry was tough, cold, shrewd, and cautious. He was also hardworking and carefully tended to the details of governing. Henry used a variety of methods to keep the nobles under control and to guarantee his security. Unlike previous kings, for example, he often disregarded rank when appointing people to high office. He sought instead such qualities as ability and loyalty.

Henry made several important alliances. He arranged a marriage between his son Arthur and Catherine of Aragon, daughter of King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella of Spain. After Arthur died, the king secured the young widow, and her dowry, for his younger son, Henry. He also negotiated a marriage between his daughter Margaret and James IV of Scotland. Henry kept England out of European wars and accumulated a sizeable fortune. He died in 1509.

Henry VIII

succeeded his father. From about 1514 to 1529, Cardinal Thomas Wolsey was Henry’s chief minister and handled much of the day-to-day business of governing. For most of the 1530’s, Thomas Cromwell served as chief minister. Yet Henry maintained firm control over broad policy and all final decisions. He was an enthusiastic, forceful, and intelligent ruler. But he was also egotistical and extravagant and would turn on those who served him if they could not or would not meet his demands. Henry was also a patron of the arts, especially music, and did a great deal to build up the English navy.

Henry’s wife, Catherine of Aragon, bore Henry six children, but only a daughter, Mary, survived infancy. Henry and his councilors believed that a male heir to the throne was essential to prevent any more wars over the succession. He determined to annul his marriage to Catherine and marry again in the hopes of having a son to succeed him. However, Pope Clement VII did not want to grant Henry an annulment. Henry secretly married Anne Boleyn in January 1533. He then denied that the pope had authority over England. Henry and Cromwell had Parliament pass acts that led to the English church’s break with the Roman Catholic Church. In 1534, the Act of Supremacy recognized the Church of England as a separate institution and the king as its supreme head. These actions occurred while the Reformation, the religious movement that gave birth to Protestantism, was spreading across northern Europe.

Henry VIII’s marriage to Anne Boleyn produced a second daughter, Elizabeth, but no son. Henry had Anne executed in 1536 on charges of unfaithfulness. It was not until his third marriage, to Jane Seymour, that Henry’s longed-for son, who was named Edward, was born. Henry’s later marriages to Anne of Cleves, Catherine Howard, and Catherine Parr produced no children.

Edward VI

was only 9 years old when he became king in 1547. For the first two and a half years of Edward’s reign, his uncle Edward Seymour, the Duke of Somerset, served as protector of the kingdom. In 1549, John Dudley, Earl of Warwick, overthrew Somerset. Dudley became Duke of Northumberland in 1551.

As he lay gravely ill from a fever and severe lung infection, Edward decided to will the throne to his Protestant cousin Lady Jane Grey. Jane was a granddaughter of Henry VIII’s younger sister, Mary. Edward was a devout Protestant, and neither he nor Northumberland wanted Edward’s half sister Mary, a Roman Catholic, to succeed to the throne. In addition, Northumberland had Jane marry his son, Lord Guildford Dudley, shortly before Edward died. He hoped to retain his hold over the kingdom. Edward died in 1553, at the age of 15.

Although Lady Jane Grey was proclaimed queen, the plans of Edward and Northumberland failed, and Mary was recognized as queen. Mary had Northumberland executed and imprisoned Jane and Guildford Dudley. Following an unsuccessful Protestant-led rebellion in early 1554, Mary also had Jane and her husband executed.

Mary I

was England’s first queen regnant—that is, she was the first woman to rule in her own right. During her short reign, from 1553 to 1558, England lost Calais, its last possession in France. Mary’s marriage to Philip II of Spain led to an unpopular alliance with Spain. Under Mary, England officially became a Roman Catholic country again. Mary’s government persecuted and killed many Protestants, and she became known as “Bloody Mary.” Mary died before she could firmly reestablish Roman Catholicism in England. Her half sister Elizabeth, a Protestant, succeeded her.

Elizabeth I

was a mature and educated woman of 25 when she became queen in 1558. During the first part of her reign, she consolidated her authority, cut England’s remaining ties with the pope, and strengthened the Church of England. During the second part of her reign, Elizabeth was dragged into a prolonged war against Spain. Such able captains as Sir Francis Drake and Sir John Hawkins served Elizabeth during the war. Elizabeth showed good judgment by employing such talented statesmen as William Cecil, Lord Burghley, and his son Robert.

Elizabeth’s personality and charm appealed to the leaders of her country. But she had several quarrels with Parliament over her refusal to marry or to name a successor to the throne. Elizabeth glorified the monarchy and provided her subjects with a national symbol of state. England’s overseas expansion began during Elizabeth’s reign.

The Stuarts in Scotland and England

David II of Scotland had no children. His nephew, Robert the Steward, succeeded him in 1371. Robert was the son of David’s half-sister, Marjorie. Robert’s ancestors had become known by the name Stewart (later also spelled Stuart) because they held the office of High Steward of Scotland. Stewart was the old Scots spelling of Steward. The Stuarts ruled Scotland for more than 300 years. They also became kings of England after Queen Elizabeth’s death in 1603. Much of the Stuart period in Scotland was a time of great unrest, partly because so many Stuarts inherited the throne in infancy.

Robert II

was 55 when he became king. Many Scottish nobles questioned his right to the throne, beginning a long power struggle between the Stuarts and the Scottish nobles. In the early years of his reign, Robert was cautious and tried to balance the power of the nobles and the monarch. In 1384, his oldest son, John of Carrick, became guardian of the kingdom and took over most policymaking decisions from his aging father. John pursued a more vigorous expansionist policy, which increased conflict with England. In 1388, John was severely injured by a horse and his brother Robert, Earl of Fife, became guardian. After Robert II died in 1390, John succeeded him and took the name Robert III.

Robert III

was king in name only. His brother, who became Duke of Albany, continued as guardian. In 1399, the power and title of guardian passed to Robert III’s son, David, Duke of Rothesay. In 1402, Albany captured Rothesay, who died mysteriously soon afterward. Meanwhile, a war raged on and off between Scotland and England. In 1406, Robert III sent his surviving son, James, to France to protect him from Albany. But the English captured James and imprisoned him in the Tower of London. Robert III died in 1406, soon after James had been kidnapped.

James I of Scotland.

James, still a prisoner, became king in 1406, at the age of 12. Albany was appointed governor of the realm. Albany died in 1420, and his son, Murdoch, Duke of Albany, succeeded him as governor. During the government of the two Albanys, the Scottish nobles seized royal lands and revenues.

In 1424, after holding James prisoner for 18 years, the English freed him in exchange for a ransom. James proved an energetic king. He curbed the powerful nobles, reformed the Scottish legal system, and imposed taxes to restore the royal revenues. He also made some use of parliaments. James arranged a marriage between his oldest daughter, Margaret, and the son of the French king to strengthen Scotland’s traditional alliance with France.

James was an athletic man, as well as a poet and musician. He wrote a love poem titled The Kingis Quair (The King’s Book). The poem described his imprisonment and his courtship of his wife, Lady Joan Beaufort, a granddaughter of Edward III of England. James made many enemies, some of whom murdered him in 1437. He left a 6-year-old son, James II.

James II

was left in the custody of his mother, Queen Joan. Archibald, fifth Earl of Douglas, became lieutenant governor of Scotland, but proved ineffective. He died of the plague in 1439. Several noble families then fought over control of the young king. From 1444 to 1452, William, the eighth Earl of Douglas, dominated Scotland. Starting about 1450, James II ruthlessly brought the powerful noble families under his own control. The king himself stabbed William to death in 1452. In 1460, James died after a cannon exploded while he was besieging Roxburgh Castle, then held by the English. He, too, left a child to succeed him.

James III

was only 8 years old when he became king. In 1466, he came under the control of the Boyd family, who enriched themselves while they managed state affairs. They also arranged a useful marriage between James and Margaret of Denmark. The marriage made the Orkney and Shetland islands part of Scotland. Despite making important political and administrative reforms, James III became personally unpopular with the nobility. In 1488, a group of nobles defeated and killed James. This group included his son, also named James.

James IV,

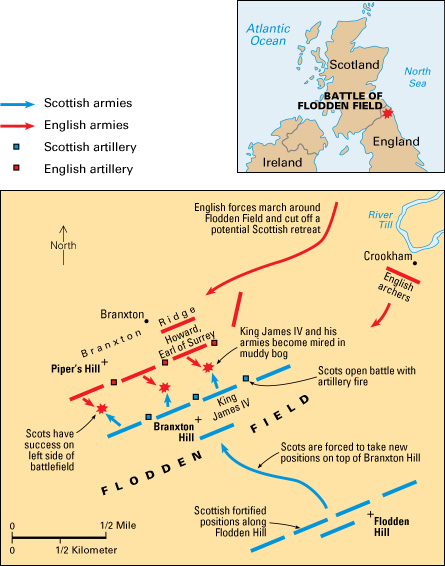

the son of James III, was 15 when he came to the throne. He made legal reforms, vigorously enforced laws to control his powerful barons, and built up a navy. In 1502, James made peace with England and, soon afterward, married Margaret Tudor, the oldest daughter of Henry VII of England. Through this marriage, the Stuarts later claimed the throne of England. In 1512, James signed a defense treaty with Scotland’s old ally, France. This treaty led James into a war with England the following year. The English defeated and killed James at the Battle of Flodden in 1513.

James V,

the son of James IV, succeeded his father at the age of 17 months. During his boyhood, the Scottish lords continually quarreled for power. James began to rule for himself at the age of 16. He was extremely supportive of the French, a fact that eventually drew James into a war against his uncle King Henry VIII of England. The English decisively defeated the Scots in 1542. James died soon afterward, leaving the throne to his 6-day-old baby daughter, Mary.

Mary, Queen of Scots,

grew up in France as a Roman Catholic. While she was in France, Scotland became a Protestant country. In 1558, Mary married the dauphin (crown prince) of France. Mary’s husband became King Francis II of France in 1559.

Francis died suddenly in 1560. Mary returned to Scotland in 1561, a Roman Catholic queen of a newly Protestant country. In 1565, she married her cousin, Henry Stuart, Earl of Darnley. In early 1567, Darnley was mysteriously murdered. Soon afterward, Mary married the Earl of Bothwell, whom many people believed was a conspirator in Darnley’s murderer. As a result of this marriage and of Mary’s religion, her subjects rebelled against her. They imprisoned her and forced her to give up the throne later in 1567. She was succeeded by James VI, her son by Lord Darnley. Mary escaped in 1568 and raised a small army, but most people in Scotland opposed her. Mary’s forces were defeated, and she fled to England.

Mary was next in line for the English throne after her cousin Queen Elizabeth I. She had refused to recognize Elizabeth as queen. Beginning in 1569, Mary supported a series of plots to overthrow her. As a result, Elizabeth imprisoned Mary for nearly 19 years and eventually had her executed for treason.

After Mary’s execution, the succession for the English throne passed to James VI. Thus, when Elizabeth died in 1603, the English and Scottish crowns became one. James VI of Scotland also became James I of England. He was the first monarch to rule England, Ireland, Scotland, and Wales simultaneously.

James I of England

was a scholar who wrote works on theology, witchcraft, and the divine right of kings, the belief that a monarch’s right to rule came from God. He had great success ruling Scotland but handled the English Parliament tactlessly. James usually had the sense to compromise when necessary, but his talk of absolute royal power alarmed the members of Parliament, especially those in the elected House of Commons.

James also faced opposition from the Puritans, a religious group who wanted to “purify” the Church of England. In 1604, he called the Hampton Court Conference to settle disagreements within the Church of England. However, James refused to bring about the reforms the Puritans sought, except for a new translation of the Bible, now called the King James Version.

King versus Parliament.

Charles I, who succeeded James in 1625, also believed in absolute royal power. Charles was also far less compromising than his father. From 1625 to 1629, Charles called three parliaments and dissolved each one because the members opposed his political, fiscal, and religious reforms. In 1628, he reluctantly accepted the Petition of Right, a document drawn up by Parliament that limited the power of the king. From 1629 to 1640, Charles ruled without Parliament and raised money by methods that many people considered illegal. This period became known as the Eleven Years’ Tyranny.

The Puritans also distrusted Charles. Although he belonged to the Church of England, his fondness for ritual led the Puritans to believe that Charles was secretly a Catholic. The fact that his wife, the French Princess Henrietta Maria, was openly Catholic fed their suspicions.

In 1639 and 1640, Charles went to war with the Presbyterian Scots because they refused to accept the new Prayer Book that he had imposed upon them. The Scots defeated the English and forced Charles to call a Parliament in November 1640 to raise money to pay them off. Known as the Long Parliament, it sat until 1653 and again briefly in 1660. The Parliament insisted that Charles grant major constitutional reforms.

The conflict between Charles and Parliament came to a head in the autumn of 1641, when the Irish rebelled against English settlers in Ireland and massacred several thousand of them. Charles refused to let Parliament control the army raised to crush the rebellion. This dispute helped lead to a civil war that broke out between the king and Parliament in 1642.

People who supported the king in the war were called Royalists or Cavaliers. Many of Parliament’s greatest supporters were Puritans, who were called Roundheads because they cut their hair short. The Puritans changed the administrative structure of the Church of England and tried to force many of their religious beliefs on the people.

During the war, Oliver Cromwell emerged as a leader in the army and in Parliament. In 1646, Charles surrendered to Scottish troops, but the next year, they turned him over to the English Parliament. Attempts to negotiate a settlement between the king and Parliament failed. In 1647 and 1648, the army removed the more moderate members from Parliament. The remaining members set up a special court, which tried Charles for treason. He was beheaded in 1649.

Cromwell established a republic known as the Commonwealth. In 1653, he dissolved what was left of the Long Parliament and ruled as lord protector with the army’s backing. He called two more parliaments but was unable to work effectively with them. Cromwell died in 1658. His son Richard, who succeeded him, became known as “Tumbledown Dick,” owing to his lack of leadership ability. In 1660, General George Monck and his army forced the election of a new Parliament, which then restored the son of Charles I to the monarchy. A period called the Restoration followed.

The Restoration.

Charles II was clever and charismatic, but he trusted nobody and was disloyal to his ministers. Charles accepted the fact that he had less power than earlier English kings and had to share control of the government with Parliament. He reinstated the earlier structure of the Church of England and barely tolerated the strict morals of Protestant Nonconformists, Protestants who refused to conform to the official church.

During the Restoration, two political parties emerged—the Tories and the Whigs. In general, Tories supported royal authority and the Church of England. Whigs emphasized Parliamentary authority and wanted greater toleration for Protestant Nonconformists. Also during the Restoration, the arts and sciences flourished. The theater, which the Puritans had banned, was revived. In 1662, Charles helped establish the Royal Society, which became one of the world’s most prestigious scientific organizations.

Charles’s successor, his brother James II, took the throne in 1685. In Scotland, he reigned as James VII. James was a convert to Roman Catholicism. He alarmed English leaders when he bypassed laws to put Catholics in positions of authority. James also interfered with local governments in hopes of filling Parliament with his supporters. He hoped to make England a Catholic country again. The English people, mostly Protestants, put up with James as long as the heir to the throne was his daughter Mary, also a Protestant. But the birth of a son, James Francis Edward Stuart, in 1688 ended their hope that a Catholic monarchy would be temporary.

A group of aristocrats invited Mary and her husband, William of Orange, the ruler of the Netherlands and the son of Charles I’s oldest daughter, to invade England. In 1688, William landed in England. James fled to France. People called the events of 1688 the Glorious Revolution. In 1689, the parliaments of England and Scotland invited William and Mary to rule jointly. They became William III and Mary II.

The English and Scottish parliaments also passed the Bill of Rights of 1689, which prohibited the monarch from suspending the laws of the land. The Bill of Rights and the Act of Settlement of 1701 established the succession to the throne and declared that no Catholic could become monarch. Mary died in 1694. She had been a popular ruler. After William died in 1702, few people lamented his death. He had been a cold, reserved man and had involved England in a war with France to protect the Netherlands.