Phillip, Arthur (1738-1814), was the first governor of New South Wales, Australia. As governor, he established European settlement in Australia. He also followed a career in the Navy, reaching the rank of admiral.

Early life.

Phillip was born on Oct. 11, 1738, in London, the son of a German-born language teacher. His mother was previously married to a naval officer. Through her connections, a place for Phillip was found in the Greenwich school for the sons of seamen in 1751. He served his apprenticeship as a merchant seaman aboard the Fortune.

Phillip joined the British Royal Navy during the Seven Years’ War. He served during the British capture of Havana, Cuba. In 1763, he retired on half pay as a lieutenant. From 1763 to 1774, Phillip spent his time farming. From 1774 to 1778, he served with the Portuguese navy in the war with Spain. In 1781, Phillip was promoted to the rank of captain in the British Royal Navy.

In 1786, he was appointed as the first governor of New South Wales and given command of the First Fleet. The site selected for the new settlement in New South Wales was Botany Bay. The First Fleet consisted of H.M.S. Sirius and H.M.S. Supply, six transports to carry the convicts, and three supply ships.

Botany Bay.

The First Fleet arrived in Botany Bay between Jan. 18 and Jan. 20, 1788, after an eight-month voyage from Britain. The fleet carried convicts and marines to guard the prisoners. It also carried provisions, including seeds for planting, livestock, and food supplies to sustain the colony until the first crops were harvested.

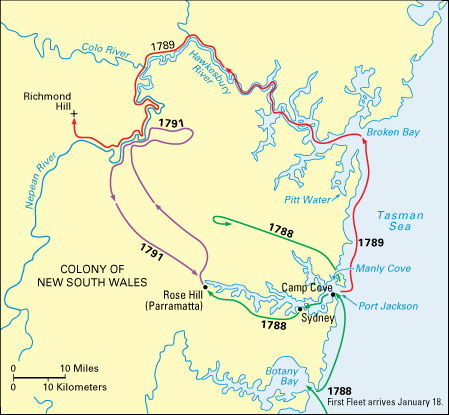

Unfortunately, Botany Bay proved to be a poor site to establish the new colony. It had a low-lying, marshy foreshore. The bay close to the shore was too shallow to provide safe anchorage for the ships, and there was no protection from the wind. There was little fresh water. On January 21, Phillip took three long boats north along the coast to search for another site for the settlement.

Port Jackson.

Later on January 21, Phillip entered Port Jackson. There he found a natural deepwater harbor that was protected from the wind. Rowing north, he eventually landed at Sydney Cove. It had a good natural harbor and a running stream of fresh water, which was later to be called the Tank Stream. The cove was named in honor of Lord Sydney, the secretary of state for the home office.

Phillip returned to Botany Bay and began to arrange for the fleet to sail north. Arrangements to move the fleet to Sydney Cove had been completed by January 26. The male convicts and most of the marines went ashore on January 27 and 28. The convicts were set to work cutting down trees and clearing an area for the new settlement. By early February, the settlement had taken shape. On February 6, the women convicts were brought to the site. Phillip’s commission was read on February 7, and the colony was proclaimed. A European settlement had been established in Australia, but its hold on the new country was far from strong.

The colony’s early years.

Phillip’s major task was to make sure the colony would survive. It was an extremely difficult job. Buildings had to be erected, crops planted, and discipline maintained.

As governor, Phillip was, in effect, the government of the colony. He performed administrative duties that ranged from writing reports for the home government to making appointments and ordering punishments for those convicted of committing offenses. He only had the assistance of the convicts. Most convicts were city or town people with few of the skills needed to establish a new colony, and according to observers, most were also lazy. Phillip’s job was made even more difficult by the inexperience of many of the officials and the refusal of the marines to undertake nonmilitary duties, such as supervising convicts at work.

The first problem Phillip faced was the supply of food. The colony had enough supplies to last about a year. By that time, the first crops were to have been harvested. But the first crops of wheat, rice, and barley failed. Farm animals died or vanished into the bush.

Some native animals were killed for food, but the settlement relied mainly on the salt meat brought with the fleet. By late 1788, supplies were running low. Phillip sent the ship Sirius to the Cape of Good Hope to buy more food. He also introduced rationing, which limited the amount of food each person was given at each meal. Everyone, including Phillip, received the same ration.

Phillip was not prepared to wait for supplies coming from outside the colony. In late 1788, he led expeditions looking for land better suited for cultivation than that at Sydney Cove. He chose Rose Hill, near Parramatta, as the site for a government farm. The farm was established by mid-1789, and new crops were planted.

Severe food shortages continued throughout 1789, and rations were further reduced. The harvest at the end of 1789 was successful, but it did not produce enough grain. By early 1790, starvation threatened the colony. In April, Phillip sent the Supply to Batavia (now Jakarta) to buy food supplies. The arrival of the Second Fleet with its supply ships in June helped relieve the food shortage. With the return of the Supply in October, there was no longer a threat of starvation in the near future. Conditions improved slowly during 1791. By 1792, the colony was on the way to self-sufficiency in most basic foodstuffs.

Ill health among the colonists was also a major problem facing the new governor. Scurvy, a disease caused by lack of the vitamins in fresh fruit and vegetables, had been contained during the voyage from Britain by providing the convicts with fresh food. But scurvy struck soon after landing, as rationing reduced the quality of the diet. Dysentery, an illness affecting the digestive system, was also a problem. A tent hospital was erected in the colony, but treatment of the sick was difficult because there was not enough medicine. The arrival of the Second and Third fleets made the situation worse. A large proportion of convicts were seriously ill on arrival.

Canvas tents were the main means of shelter in the colony for its first two years. Phillip’s attempts to build better buildings were frustrated by a severe shortage of carpenters and other skilled builders. Stores had been built by mid-1788 to protect supplies. The first roughly made huts for the marine officers had been finished by December. Temporary barracks were not completed until 1789. A kiln (an oven for baking bricks) completed in 1790 helped Phillip’s building program. But permanent barracks were not completed until 1794.

Phillip’s policies were shaped by both immediate problems and a long-term vision of what the colony of New South Wales could become. To convict administration, he brought a belief in the need for reform, which was expressed in his system of rewards for good behavior. His method of discipline was firm, even harsh by today’s standards. Generally, however, the convicts responded well to his administration. Phillip hoped to establish good relations with the Aboriginal peoples, though the policy failed. He encouraged the development of agriculture and the building of Sydney.

Phillip also saw much more in the future of New South Wales. Although few would have shared his view, he saw the colony as a new outpost of the British Empire. He saw the transportation of convicts as only one purpose for the colony. He also actively encouraged free immigrants to come to New South Wales. He believed free immigrants would be beneficial for society, would help with convict administration, and would establish a sound economy in the colony. To encourage their migration, he proposed free land grants with the promise of free convict labor for two years.

Phillip was a capable and efficient administrator. He steered the new settlement through its most difficult years. When he left, the population of New South Wales had grown to about 6,000 people. Free settlers were about to arrive in the colony and his land grant and convict assignment proposals had received official approval.

Later life.

In 1794, Phillip settled in the city of Bath, in England. Phillip returned to the Navy in 1796 as captain of the Alexander. He reached the rank of admiral a few weeks before his death on Aug. 31, 1814. He was buried in the church of St. Nicholas, in the village of Bathampton, near Bath. A memorial to him was placed in Bath Abbey.