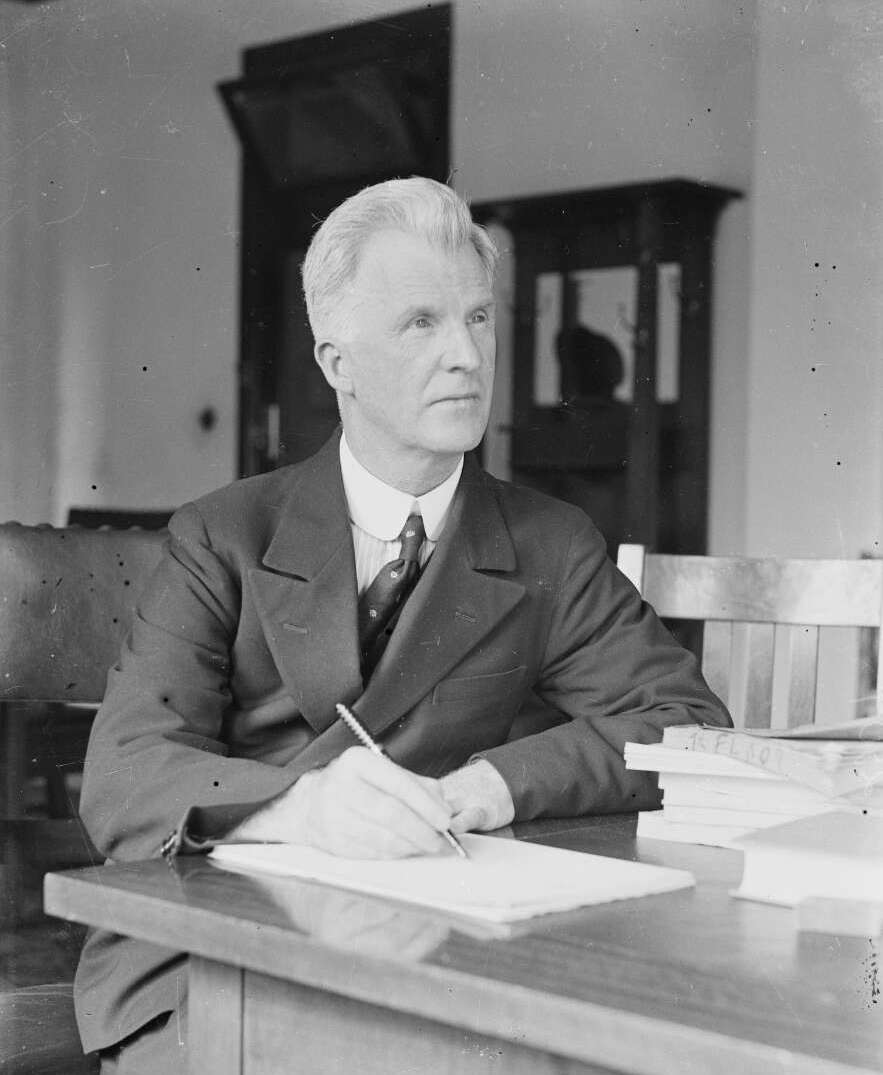

Scullin, James (1876-1953), a leader of the Australian Labor Party, was the first Roman Catholic to become prime minister of Australia. He held office from 1929 to 1932. During these years, the Great Depression—a worldwide economic slump—swept through Australia. Scullin succeeded Prime Minister Stanley M. Bruce of the Nationalist Party.

Early life

Boyhood and education.

James Henry Scullin, often called Jim, was born in Trawalla, Victoria, on Sept. 18, 1876. His parents were John Scullin, a railway worker, and Ann Logan Scullin. Both parents were Irish immigrants to Australia. Jim left school as a boy to work in a grocery store. However, he continued his education at night school. In his twenties, he became the owner and manager of a grocery store in the city of Ballarat, Victoria.

Marriage and family.

On Nov. 11, 1907, Scullin married Sarah Maria McNamara (1880-1962), a dressmaker and the daughter of a union activist in Ballarat. The Scullins had no children.

Labor leader.

In 1903, Scullin joined the Political Labor Council of Victoria, a forerunner of the Australian Labor Party. He set up branches of the Political Labor Council throughout western Victoria. In 1906, he became a part-time organizer for the Australian Workers’ Union, one of Australia’s oldest and largest unions.

Entry into politics

In 1906, Scullin became the Labor Party candidate for the seat representing Ballarat in the federal House of Representatives. He lost to Alfred Deakin, then Australia’s prime minister. In 1910, Scullin won election to the House as the representative from Corangamite, a region in southwest Victoria. He lost the seat in 1913, however. He returned to Ballarat, where he became the managing director and editor of The Evening Echo, a Labor newspaper.

In 1918, Scullin was elected president of the Victoria branch of the Labor Party. In 1922, he won the Melbourne seat of Yarra in a by-election (special election to fill a vacancy). He kept the seat for almost 28 years, through 10 elections.

Prime minister

On April 26, 1928, the Labor Party elected Scullin as its leader. In the general election of Oct. 12, 1929, Labor won a large majority in the House of Representatives but failed to win control of the Senate. Scullin took office as prime minister on October 22.

Scullin held several other Cabinet portfolios (official areas of responsibility) in addition to that of prime minister. From October 1929 to January 1932, he served as minister of external affairs and minister of industry. In July 1930, he added the role of treasurer of Australia after his treasurer and deputy prime minister, Edward G. (Ted) Theodore, resigned. Theodore stepped down because he had been accused of financial wrongdoing while serving as premier of Queensland. Queensland did not charge him with any crime, however, and in January 1931, Scullin reappointed him as treasurer.

Scullin persuaded King George V of the United Kingdom to appoint the first Australian-born governor general, Sir Isaac Isaacs. Sir Isaac took office in 1930. The governor general serves as the representative of the British monarch, who is the symbolic head of Australia’s federal and state governments.

Before becoming prime minister, Scullin had often criticized the costliness of The Lodge, the prime minister’s official residence in Canberra. To save the government money, the Scullins lived in a Canberra hotel during sessions of Parliament and in their home in Melbourne, Victoria, at other times.

Economic crisis.

Scullin became prime minister at a bad time. Two days after he took office, the stock market in the United States crashed. The Great Depression soon followed. The Depression hit Australia hard. Many banks failed. Prices for manufactured goods dropped sharply, reducing the income Australia earned from exports. Unemployment rose rapidly. In his 1930 budget speech, Scullin described the situation as a ”financial depression without parallel.”

Australia still owed large debts to British banks for loans it had taken out to pay for World War I (1914-1918). In 1930, Scullin’s government asked the British government if it could pay reduced interest on its war debt or delay payment of the interest. Many Australian leaders pointed out that their country had acquired the debt helping to defend the United Kingdom.

The British government referred the question of Australia’s debts to the Bank of England, which wanted to learn more about Australia’s financial condition. The bank sent one of its directors, Sir Otto Niemeyer, to examine Australia’s finances. The English banker urged sweeping changes in Scullin’s economic policies to ensure that Australia could repay its loans. Sir Otto met with federal and state leaders at a special conference in Melbourne in August 1930. He told them that the government must balance its budget and Australians must accept a lowered standard of living. On Sir Otto’s advice, the federal and state governments agreed to decrease welfare payments, cut salaries and wages, abandon public works projects, and increase taxes. This plan became known as the Melbourne Agreement.

The Scullin government took other steps to follow Sir Otto’s advice. In January 1931, the Commonwealth Court of Conciliation and Arbitration, a government court that settled labor disputes, ordered a 10 percent cut in basic wages. In June, the premiers of Australia’s six states agreed to a strategy called the Premiers’ Plan. The plan aimed to reduce government spending by 20 percent by increasing taxes and by lowering pensions, wages, and interest rates. The government’s actions caused deep resentment among Australians who were already suffering economic hardships from the Depression.

Opposition in Parliament.

Throughout his time in office, Scullin had difficulty getting his proposals enacted into law. The Labor Party had a large majority in the House but only 7 of the 36 seats in the Senate. As a result, the Senate blocked passage of many bills.

One of the most important bills introduced during Scullin’s term was enacted after he left office. The Australian Broadcasting Commission Act of 1932 established a government agency, now called the Australian Broadcasting Corporation, to provide national radio service.

Scullin not only lacked supporters in the Senate but also faced deep splits in his party in the House. One of the splits involved John T. (Jack) Lang, the Labor premier of New South Wales. Lang opposed the Melbourne Agreement and Scullin’s other efforts to reduce government spending. Several of Lang’s supporters in Parliament quit the Labor Party and formed a group called Lang Labor.

In February 1931, two of Scullin’s Cabinet ministers, Joseph A. Lyons and James Fenton, resigned from their positions to protest the reappointment of Theodore as treasurer. In March, Lyons, Fenton, and three other members of Parliament resigned from the Labor Party and threw their support to the opposition, the conservative Nationalist Party. Lyons and his followers merged in May with the Nationalist Party to form a new party called the United Australia Party. Lyons became the party leader.

In November 1931, a member of the Lang Labor faction accused Treasurer Theodore of corruption in distributing unemployment relief. Scullin decided to seek a vote of confidence. In such a vote, the legislature decides whether to support a matter of importance to the prime minister. Lang Labor joined the opposition in the House and passed a no-confidence motion against Scullin on Nov. 25, 1931. Governor General Sir Isaac Isaacs dissolved Parliament two days later, and a general election took place on Dec. 19, 1931. The United Australia Party won in a landslide, and Lyons replaced Scullin as prime minister on Jan. 6, 1932.

Later years

Scullin stayed on as leader of the Labor Party until Oct. 1, 1935, when he resigned because of ill health. He remained in Parliament for 17 more years, until December 1949. He died on Jan. 28, 1953.