Borden, Sir Robert Laird (1854-1937), served as prime minister of Canada throughout World War I. As prime minister from 1911 to 1920, Borden made his greatest achievements in helping Canada win a more independent role in world affairs. He believed that his country should support British Empire policies, but only if Canada had an “adequate voice” in making the policies. Borden’s government also reformed the Canadian civil service and gave women the right to vote in national elections.

Borden led the Conservative Party from 1901 until he retired as prime minister in 1920. Under his strong leadership, the Conservatives defeated the Liberals in the 1911 election after being out of power for 15 years. The Liberals, under Sir Wilfrid Laurier, had ruled Canada since 1896.

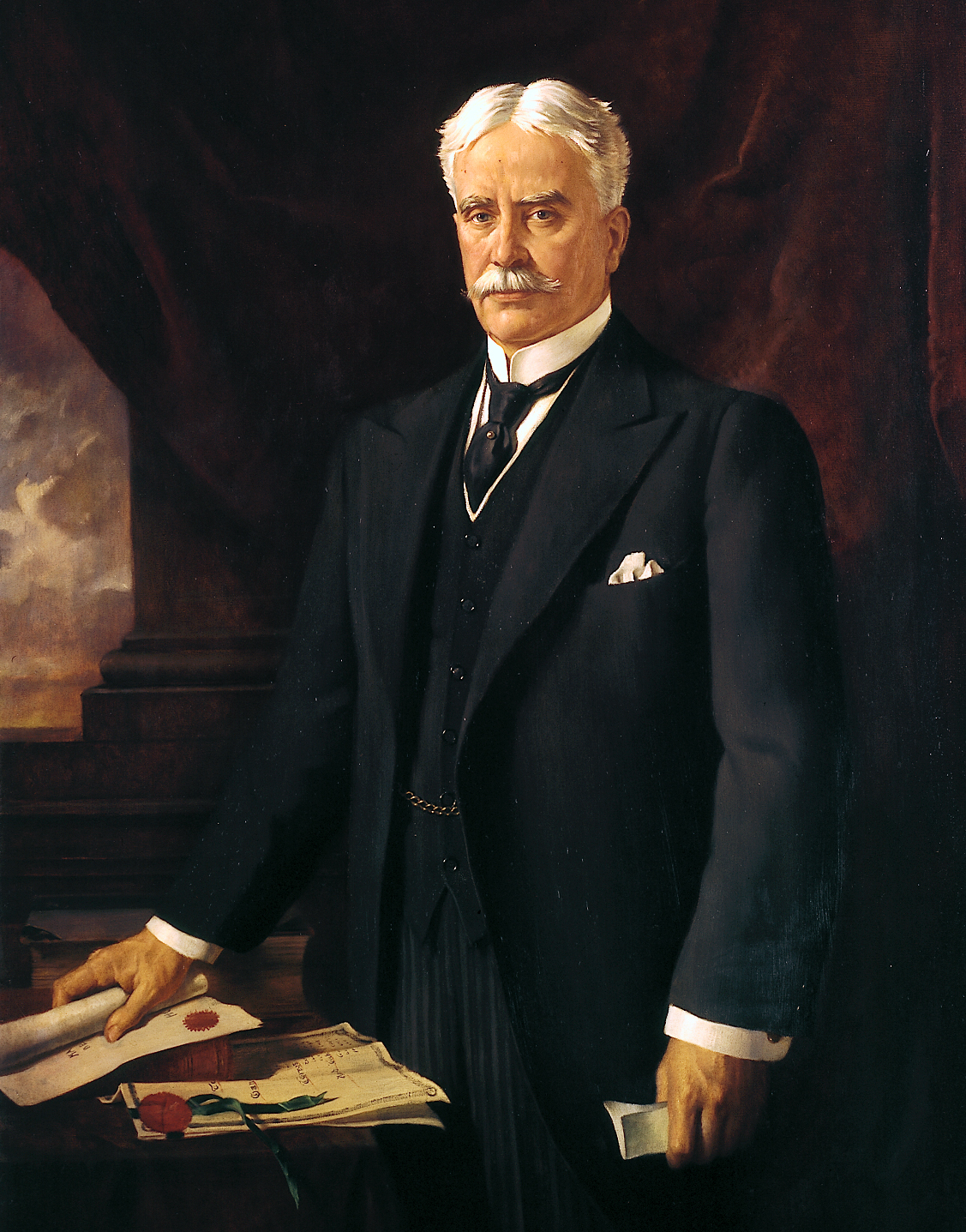

A sturdy man, Borden had a cheery, dogged courage. He had a bristling mustache and parted his long, silver hair in the middle. The effect made him look lionlike. Although a lawyer by profession and accustomed to public speaking, he was not a great orator.

Borden entered public life reluctantly in 1896. He would have preferred to remain a lawyer. A few years later, when the Conservatives asked him to lead their party, he at first refused. He eventually accepted, however, because of his sense of duty, and he came to appreciate his position of leadership.

Early life

Robert Laird Borden was born on June 26, 1854, in the village of Grand Pre, Nova Scotia. He was the eldest of the four children of Andrew Borden and Eunice Jane Laird Borden. His father, who was a farmer at the time of the boy’s birth, later became a railroad stationmaster.

Borden’s ancestors came from England and Scotland by way of New England. One had landed in Rhode Island in 1638. The families of both his parents had moved to Nova Scotia from New England in the 1700’s.

Robert grew up in the Gaspereau Valley, one of the most beautiful regions of Canada. In the winter, Robert went sledding with his friends on the snowy hillsides. The boy attended the Anglican (Episcopal) Church with his father, and sometimes the Presbyterian Church with his mother.

He went to the local school, known as the Acacia Villa Seminary. Robert did especially well in Latin, Greek, and mathematics. This pleased his mother, whose father had been a student of ancient languages. Borden was such a good student that in 1869, when only 14, he became a teacher at the school. In 1873, he accepted a position at a school in Matawan, New Jersey, and taught there for about a year.

In 1874, Borden returned to Canada and decided to become a lawyer. Nova Scotia had no law school at that time, so Borden studied law as a clerk in a Halifax law firm. He was admitted to the bar in 1878. Borden began practicing law in Halifax and then in Kentville, Nova Scotia. In 1882, he joined the Halifax firm of Graham, Tupper, and Borden as a junior partner. Important cases took Borden before the Supreme Court of Canada and even before the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom. This committee was the final court of appeal for nations belonging to the British Empire.

On Sept. 25, 1889, Borden married Laura Bond of Halifax. Borden spoke of his wife as the person “whose devotion and helpfulness … have been the chief support of my life’s labours.” The Bordens had no children.

Early public service

Entry into politics.

Borden had been brought up as a Liberal, but he left the party in 1886. He did so because the Liberal leader in Nova Scotia had called for the possible withdrawal of Nova Scotia from the Canadian federation. In 1896, the Conservative Party was desperately looking for new people. Halifax Conservatives thought Borden would be an excellent candidate.

Borden was reluctant to enter politics. “At first I flatly refused,” he wrote later. “I had no political experience; no political ambitions had ever entered my mind and I was wholly devoted to my profession.”

Borden finally agreed to run for Parliament. He won election even though the Conservative government of Prime Minister Charles Tupper was defeated.

Borden had some difficulty adjusting to his new surroundings. “The nervous strain of learning to speak in parliamentary debate I found rather severe,” he wrote, “although for many years I had been accustomed to speak in court and before juries.”

Conservative leader.

In 1900, Borden was reelected to Parliament. But the Conservative Party again met defeat. In 1901, Sir Charles Tupper, the father of Borden’s law partner, resigned as Conservative leader. The party asked Borden to be the new leader. Borden again refused at first, but the Conservatives did not give up. “Finally,” he wrote later, “under great pressure, I agreed to accept the task for one year. …” Borden led the party for 19 years.

Borden faced a difficult situation that tested his courage and his capacity to work. The Liberals had come to power in 1896 under Wilfrid Laurier, a brilliant French-Canadian orator. Canada had prospered during Laurier’s rule, and immigrants and money were coming in from abroad. In addition, the country’s programs of land settlement and railway-building had been successful under the Liberals.

Borden set out to rebuild the discouraged and divided Conservative Party. His task was slow and painstaking, and by the 1904 election he had not succeeded. The Liberals won the election, and Borden himself was defeated for reelection to Parliament from Halifax. In 1905, he was reelected from Carleton, Ontario. That same year, Borden gave up his law practice and moved to Ottawa. He felt he could carry on his duties as leader more effectively in the Canadian capital.

A new Conservative program.

In 1907, Borden announced a new program for the Conservative Party. He had been influenced by the progressive ideas of the Conservative governments of Manitoba and Ontario and of American progressives. Borden called for public ownership of the telephone and telegraph systems, and of certain railways and grain elevators. He favored closer supervision of immigration and a protective tariff on imports to protect Canadian goods.

In the 1908 election, the tide began to turn in Borden’s favor. He won election to Parliament from both Halifax and Carleton, and decided to represent Halifax. The Conservatives picked up strength in the election while the Liberals lost support in Quebec and Ontario. More and more French Canadians thought Prime Minister Laurier too “British” in his policies. More and more English Canadians thought he was too “French.”

Laurier’s two biggest problems gave Borden his chance to become prime minister. These problems were Canada’s relations with the United Kingdom and with the United States.

The major problem in Canada’s relations with the United Kingdom was the question of what Canada’s role would be in any major war fought by the British Empire. British leaders believed that a war was likely with Germany. They thought Canada should raise troops and build ships to serve as part of the British forces. But Laurier felt Canada should have its own troops and ships. He also believed that the Canadian Parliament should decide when and if they should be used. In 1910, Parliament passed the Naval Service Bill to begin building a Canadian navy. Borden attacked the bill as ineffective in view of the international emergency. He felt it would take too long to build a Canadian navy. He wanted to send money to the United Kingdom for the immediate building of ships.

The main problem in Canada’s relations with the United States centered around a reciprocal trade agreement between the two nations. Borden opposed this agreement, which had been arranged by Laurier’s government in 1911. Borden believed that such close trade relations with the United States would endanger Canadian independence.

The naval bill and the trade pact became the main issues in the 1911 election. The Conservatives won their first victory in 15 years, and Robert Borden became prime minister of Canada.

Prime minister (1911-1920)

The 57-year-old Borden took office as prime minister on Oct. 10, 1911. He had to deal immediately with the question of Canadian military aid to the United Kingdom. Borden said Canada would help the United Kingdom in a major war. But he demanded that the United Kingdom give Canada what he called an “adequate voice” in making British Empire policy. The British government refused.

In 1912, Borden introduced his Naval Aid Bill in the House of Commons. This bill provided money to build warships for the Royal Navy. After weeks of heated debate, the House passed the bill. But the Senate, still controlled by the Liberals, defeated the Naval Aid Bill in 1913. King George V knighted Borden in 1914.

War leader.

Borden’s career reached its height during World War I. When the war began in 1914, Canada had neither built its own navy nor given ships to the United Kingdom. Canada went to war as part of the British Empire. For two years, Borden’s government raised, equipped, and sent to France the units that became the Canadian Corps. These units fought under Canadian command. By 1917, Canada had grown into a military power. Borden had achieved great influence among the leaders of the British Empire.

The time had come, Borden felt, to press for a greater share in policymaking. From February through May 1917, he helped organize the Imperial War Cabinet in London. This group consisted of the prime ministers of all the British Dominions. During the next two years, the Imperial War Cabinet helped plan the conduct of the war. The prime ministers also made plans for the peace that would follow the war. Members of the British Empire worked together as never before. Much of the success was due to the influence of Sir Robert Borden. He had achieved his “adequate voice.”

Conscription crisis.

Later in 1917, Borden returned home to serious military problems. Canada had lost many men in battle, and replacements were needed. Until this time, all Canadian servicemen had enlisted voluntarily. Borden believed that conscription (drafting men for military service) was now necessary to keep the Canadian forces up to strength.

“All citizens are liable to military service for the defense of their country,” Borden told Parliament, “and I conceive that the battle for Canadian liberty and autonomy is being fought today on the plains of France and of Belgium.”

Most French Canadians, including Sir Wilfrid Laurier, leader of the Liberal Party, opposed conscription. To keep unity among all Canadians, Borden wanted conscription approved by both parties in a Union Party government if possible. Laurier refused to join the proposed party. However, many Liberals in Ontario and Canada’s western provinces opposed Laurier and joined Borden’s Unionist group. With their support, Borden formed the Union Government in October 1917.

Parliament had already passed a Military Service Act providing for conscription. Farmers and labor unions opposed it. Many French Canadians in Quebec rioted in protest. The proposed draft caused a serious split between English-speaking and French-speaking Canadians. But in the December 1917 elections, the majority of voters approved the government’s action.

Postwar achievements.

In November 1918, Borden went to Europe. As the leader of Canada’s delegation to the peace conference at Versailles, France, his most important goal was to win public recognition of Canada’s new position in world affairs. Borden insisted that Canada have separate representation at the conference. Many British delegates at the conference wanted the British Empire to act as a unit. But Borden had his way. The dominions had their own representatives as though they were independent countries.

When the conference formed the League of Nations, a forerunner of the United Nations, Borden again insisted that Canada be a member in its own right. Canada also became an independent member of the International Labour Organization, an agency of the League of Nations that promoted the welfare of workers.

In May 1918, the Canadian Parliament passed a bill that reformed the nation’s civil service. The bill eliminated all patronage connected with the civil service (see Patronage ). The Union Government also passed a bill that gave women the right to vote in Canadian national elections.

Sir Robert’s health had suffered because of his constant hard work during the war years. He was close to exhaustion, and doctors told him to rest. But he continued to work. By late June 1920, he knew he had to retire from office. “I soon discovered,” he admitted, “that I had reached the end of my strength, and I quickly realized that my public career was drawing to an end.” Borden resigned as prime minister on July 10, 1920. His followers chose Arthur Meighen to take his place as their leader and prime minister.

Later years

“In looking over my diary for 1920, for the period following my retirement,” Borden wrote in his Memoirs, “I find that very frequently I have set down my satisfaction at my release from public life, as well as my conviction that it would take me a long time to recover fully my health and strength.”

A long, productive retirement lay ahead for Borden. In 1921-1922, he was a delegate of the British Empire at the Washington Conference on naval disarmament. Also in 1921, Borden delivered the Marfleet Lectures at the University of Toronto. These were published in 1922 as Canadian Constitutional Studies. In 1927, he gave the Rhodes Lectures at Oxford University. These were published in 1929 as Canada in the Commonwealth. While prime minister, Borden had been chancellor of McGill University in Montreal. From 1924 to 1930, he served as chancellor of Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario.

Sir Robert lived in Ottawa during his retirement. During his last years, he wrote and revised the story of his life. His Memoirs were published in 1938 by his nephew, Henry Borden. Sir Robert died on June 10, 1937. Lady Borden died on Sept. 7, 1940. Both are buried in Ottawa.