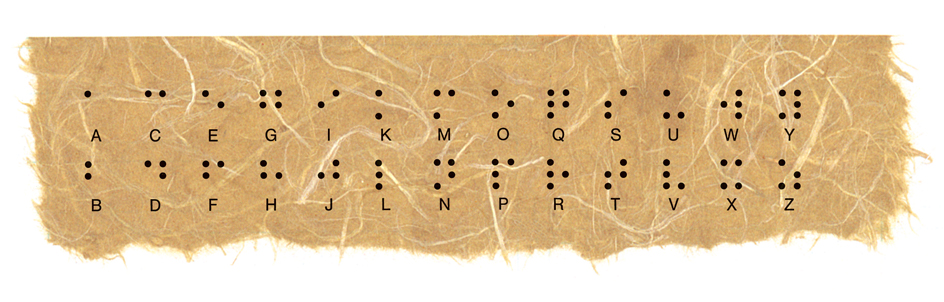

Braille, << brayl, >> is a code of small, raised dots on paper that can be read by touch. Louis Braille, a 15-year-old blind French student, developed a raised dot reading system in 1824. The idea came to him from the dot code punched on cardboard that Captain Charles Barbier used to send messages to his soldiers at night.

In 1829, Braille published a dot system, basing it on a “cell” of six dots. From the 63 possible arrangements of the dots, Braille worked out an alphabet, punctuation marks, numerals, and, later, a system for writing music. His code was not officially accepted at once. But later it won universal acceptance for all written languages and for mathematics, science, and computer notation.

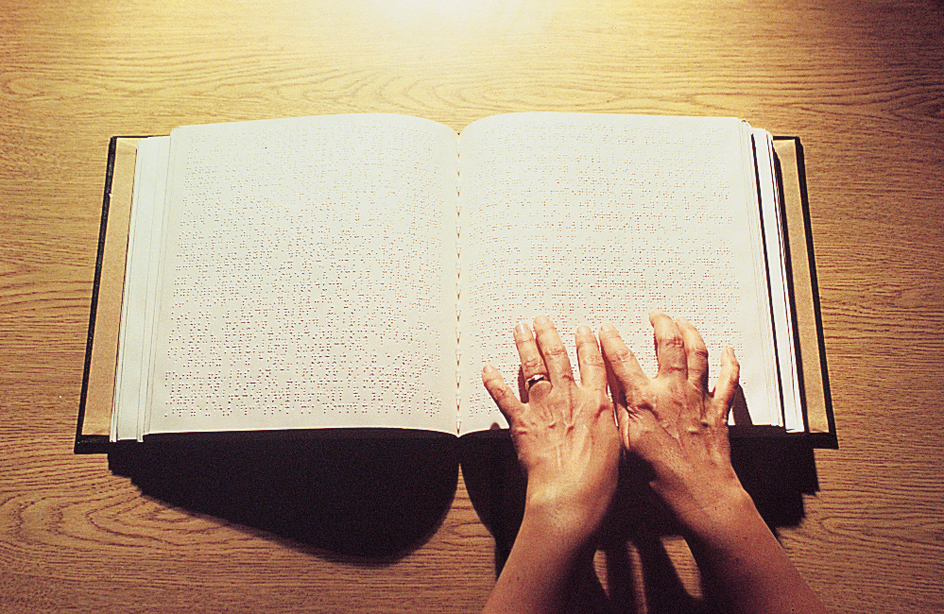

Blind people read braille by running their fingers along on the dots. They can write braille on a 6-key machine called a braillewriter, or with a stylus on a pocket-size metal or plastic slate.

Braille books are pressed from metal plates. The characters are stamped on both sides of the paper by a method called interpointing. Dots on one side of the page do not interfere with those printed on the other. In the early 1960’s, publishers began using computers to speed up production of braille books. The text is typed into a computer that automatically translates it into braille. The computer then transfers the raised braille figures onto paper or onto metal plates for use in a press. By another method, a vacuum braille former duplicates hand-transcribed braille pages on plastic sheets, which are then bound in volumes.