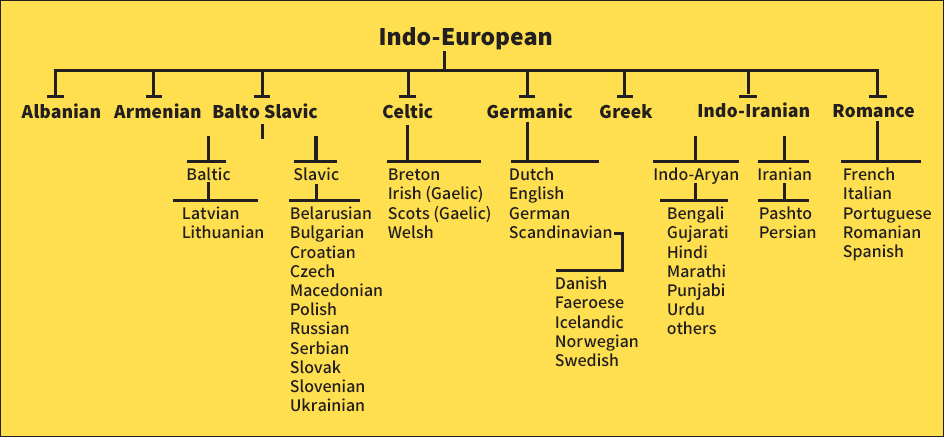

Irish language is, under the Irish Constitution, the national language of the Republic of Ireland. It is the first official language, English being the second. The Irish language belongs to the Celtic branch of the Indo-European family of languages.

As spoken today, Irish has three main dialects—Connacht, Munster, and Ulster. They differ in the way certain consonant and vowel sounds are made and in the position of the stress in many words. There are also slight differences of vocabulary and idiom.

The use of Irish in the Republic.

About 40 percent of the population of Ireland claim to be Irish speakers. But few of them use Irish in their everyday lives. Most acquire a basic knowledge of Irish at school. A knowledge of Irish is a requirement for many official positions.

The Gaeltacht.

After the mass emigrations from Ireland that took place in the 1800’s, the Irish language remained in common use in only a few rural areas, mainly in western Ireland. These areas are collectively called the Gaeltacht. In 1956, the government set up a state department to promote the interests of the Gaeltacht. See Gaeltacht.

Features of Irish.

Like English and other European languages, Irish uses letters of the Roman alphabet. Up to the 1900’s, the Irish language regularly used its own distinctive form of letters, called Gaelic script. Gaelic script is now rare except in old books. The Irish alphabet uses j, q, x, and z only in foreign and technical words. The letters k, w, and y are not normally used in modern Irish.

Nouns

in Irish are inflected (see Inflection). They are either masculine or feminine. Nouns are made plural by adding such endings as a, anna, acha, i, or ta. For example, cailin (girl) becomes cailini (girls), and brog (boot) becomes broga (boots).

Adjectives

are inflected to agree with the nouns that they qualify. So, an buachaill mor (the big boy) becomes na buachailli mora (the big boys).

Verbs

in Irish have forms that show tense (see Tense). Personal endings are added to the stem of the verb or, alternatively, separate pronouns are used with an impersonal form. For example, the stem of the verb run in Irish is rith. Its present tense forms are rithim (I run), ritheann tu (you run), ritheann se (he runs), rithimid (we run), ritheann sibh (you run), and ritheann siad (they run).

Word order.

In simple sentences in Irish, the word order is verb, subject, object. For example, the sentence John closed the door is expressed in Irish as Dhun (closed) Sean (John) an (the) doras (door). Rules exist for rearranging this basic pattern to emphasize certain words.

Pronunciation and spelling.

Irish spelling, even in its modernized form, does not fully match Irish pronunciation. Irish also has many words containing silent letters. Thus praghas, the Irish word for price, is pronounced like the English word price. Despite its difficulties, however, Irish spelling is fairly consistent.

Irish shares with other Celtic languages the feature of changing the first consonant of a word in certain grammatical situations. Such changes are called mutations. Two kinds of mutations exist in Irish, aspiration and eclipsis. For example, the Irish word for stone is cloch. But the stone is an chloch. The consonant c becomes ch by aspiration. Eclipsis is the suppression in speech of one consonant by another. For example, the Irish word for boat is bad. The phrase the sails of the boat is, in Irish, seolta na mbad. The word mbad is pronounced as if it were mad because b has been eclipsed by m.

History.

Irish belongs to the Gaelic branch of Celtic languages. Celtic is itself a branch of the Indo-European language family. The closest relatives of the Irish language are Manx (the language spoken on the Isle of Man that has nearly died out since the mid-1900’s) and Scottish Gaelic. Both have developed in modern times from Irish, which spread to Man and Scotland in the A.D. 500’s.

Irish may have been present as a spoken language in Ireland before 1000 B.C. It first appeared in a form of writing called ogam. Irish people made ogam inscriptions on stone monuments by cutting notches on either side of the stone’s edge. The notches were grouped to form a decipherable code. The earliest surviving ogam inscriptions date from the A.D. 300’s.

Old and Middle Irish.

The spread of Christianity brought the Roman alphabet to Ireland in the A.D. 400’s. Much literature began to be written in Old Irish. The Viking invasions, which began in the 800’s, and the later Anglo-Norman settlements of the 1100’s brought linguistic changes in the Middle Irish period. These changes were rapid.

Early Modern Irish,

also known as Classical Modern Irish, began to emerge about the 1200’s and lasted until the 1600’s. It set literary standards for Irish that persisted until the 1900’s. From about 1200 to 1700, English gained ground in Ireland. It was increasingly used as a language of official and legal business in such towns as Dublin, Cork, and Waterford. Irish was dominant in most rural areas.

Later Modern Irish.

By the early 1700’s, Ireland’s old social order was breaking down. Colonists and landowners from England and Scotland had largely replaced the old Irish-speaking ruling class, and the native Irish gentry who remained began to adopt English as their everyday language. Irish lived on as the language of the peasantry.

In the 1800’s, the position of Irish became weaker. In the 1830’s, the British government set up the national schools, a system of elementary education in which English was the official language. During the Great Famine of the 1840’s, about 21/2 million people, many of them Irish speakers, died or emigrated. By the end of the 1800’s, only about 500,000 people used Irish as their everyday tongue.

A scholarly revival of interest in Irish had begun in the 1780’s. Scholars began studying and publishing early Irish manuscripts. In 1893, two Irish leaders, Douglas Hyde, a writer and statesman known in Ireland as An Craoibhin Aoibhinn, and John MacNeill, a historian and law professor known in Ireland as Eoin MacNeill, founded and organization called Conradh na Gaeilge (the Gaelic League). The league aimed to “preserve Irish as the national language of Ireland and spread its use as a spoken language.” New writers emerged, such as Peadar O Laoire, Padraic O Conaire, and Patrick Pearse. They rejected the literary modes of Classical Modern Irish and turned more to the forms and rhythms of spoken language. Their efforts led to the new spelling and grammatical norms of the 1940’s and 1950’s. See also Irish literature with its list of Related articles.

The Irish language received official status soon after the establishment of the Irish Free State and had this status confirmed in the 1937 Constitution. Since then, the government has made great efforts to promote Irish, but its use as an everyday language in the Gaeltacht continues to decline.