AIDS is the final, life-threatening stages of infection with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). HIV damages the immune system, the human body’s most important defense against disease. AIDS stands for acquired immunodeficiency syndrome or acquired immune deficiency syndrome. A syndrome is a group of signs and symptoms that occur together as part of an illness.

People usually acquire HIV in one of three ways. They may become infected through (1) sexual intercourse, (2) direct exposure to infected blood, or (3) transmission from an infected mother to her baby. HIV is not transmitted through air, food, or water or by insects. No known cases of infection have occurred through the sharing of eating utensils, bathrooms, locker rooms, living space, or classrooms.

How HIV affects the body

Scientists have identified two different types of HIV. The first type identified was discovered by French researchers in 1983. It is now known as HIV-1. A second, related virus, known as HIV-2, was isolated in 1985. Both viruses cause AIDS. But HIV-1 has spread throughout the world. It is the type most associated with the global problem of AIDS. HIV-2 occurs mainly in western Africa.

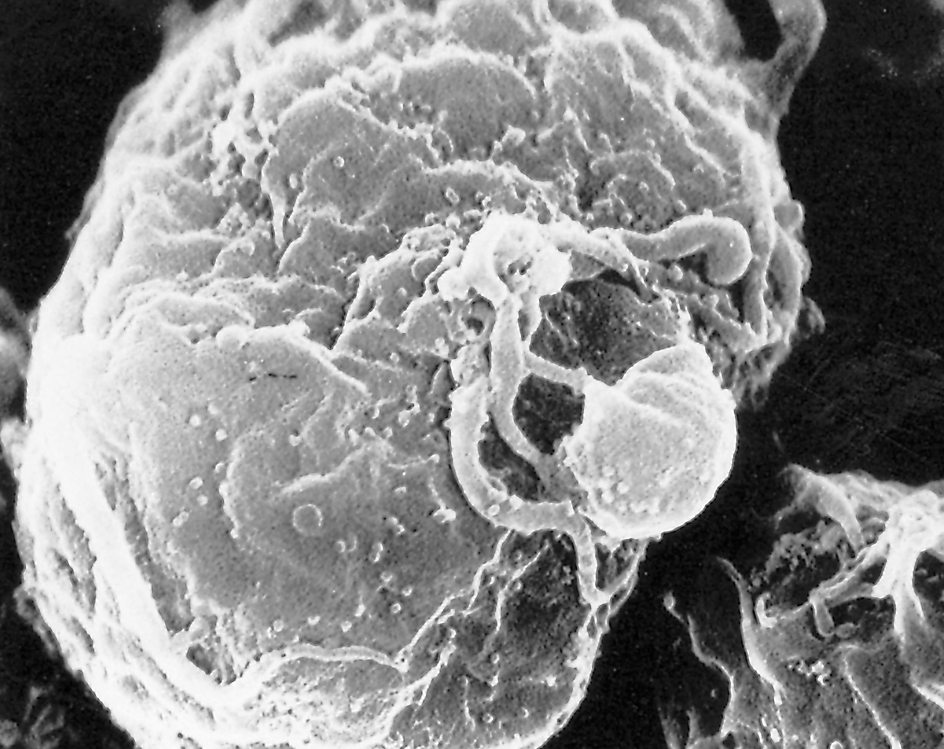

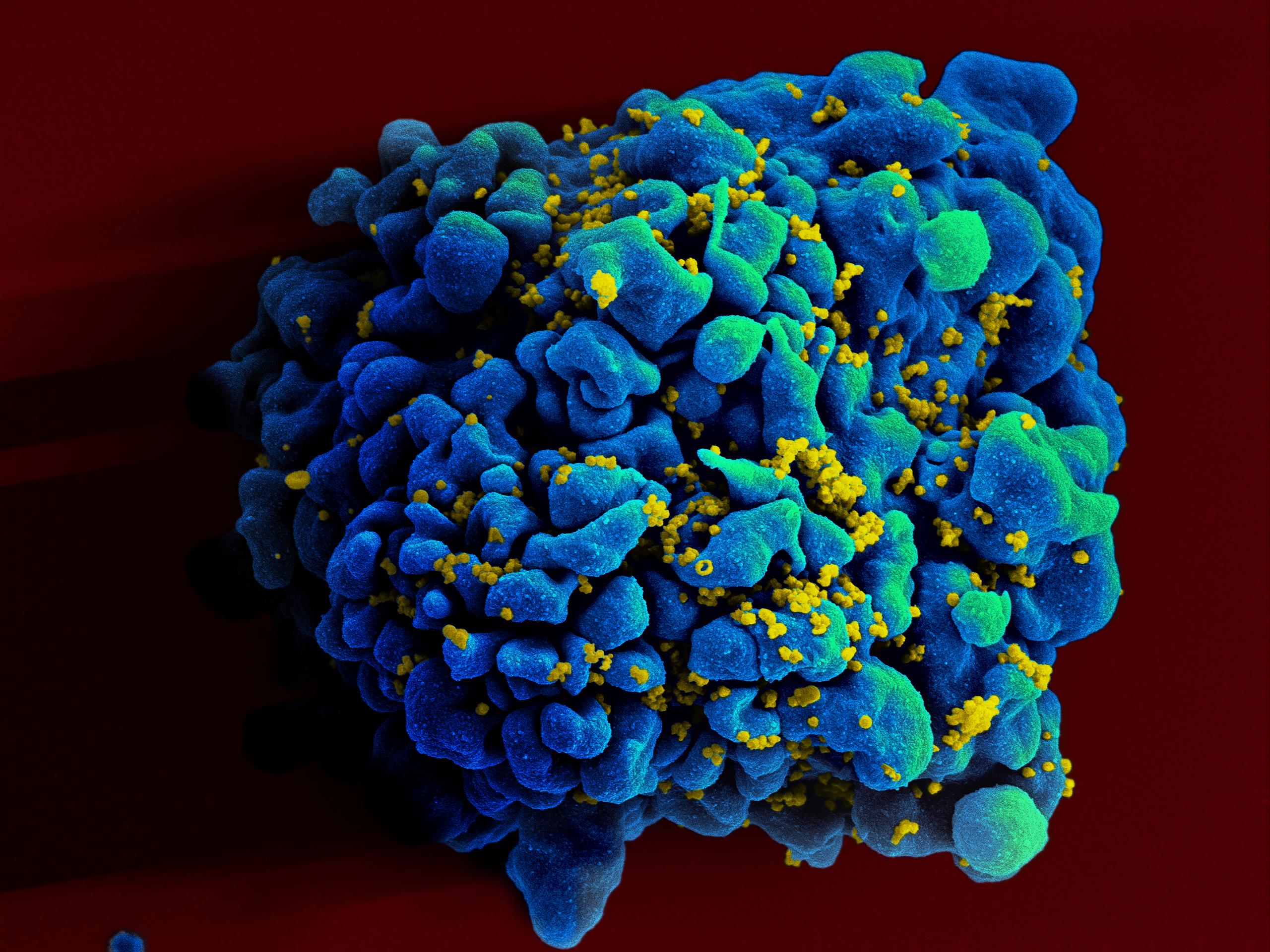

Once HIV enters the bloodstream, it infects certain white blood cells, called T helper cells and macrophages. These cells serve important functions in the immune system [see Immune system (Antigen-presenting cells); Immune system (The cell-mediated immune response)]. Together, these cells are often called CD4 cells. HIV attaches to proteins called CD4 receptors on the surface of the cells. Once attached, HIV enters the cell and inserts its own genes into the cell’s reproductive system. These genes carry the genetic “instructions” for manufacturing more HIV. The infected cell thus acts as an HIV “factory,” making thousands of copies of HIV. The HIV is then released to infect other CD4 cells throughout the body.

HIV kills the cells it infects. The immune system produces millions of CD4 cells every day. But HIV can destroy them as fast as they are produced. If left untreated, HIV infection thus disables the immune system. People then can become sick from other diseases and die.

Symptoms.

People infected with HIV eventually develop symptoms that can also be caused by other disorders. These symptoms include fever, diarrhea, tiredness, night sweats, enlarged lymph glands, loss of appetite and weight, and yeast infections of the mouth and vagina. With HIV infection, however, the symptoms are more frequent. They are more severe and last longer.

HIV infection also commonly causes a “wasting syndrome.” The syndrome results in weight loss, declining health, and in some cases, death. The virus can also infect the brain and nervous system, causing dementia. Dementia is a condition characterized by disorders of the senses, thinking, or memory. Infection of the brain may also cause problems with movement or coordination.

Opportunistic illness.

HIV damages the immune system, leaving infected people vulnerable to other infections and conditions. Many of these illnesses do not usually bother people not infected with HIV. These illnesses are called opportunistic illnesses because they take advantage of the opportunity presented by a damaged immune system. People with HIV infection may be diagnosed as having AIDS when they develop one or more opportunistic infections or one of several other severe illnesses. They may otherwise be diagnosed with AIDS when blood tests indicate that they have fewer than 200 CD4 cells per microliter (0.000001 liter) of blood.

A number of opportunistic illnesses typically affect AIDS patients. In North America and Europe, Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (PCP) is most common. PCP is an infection of the lungs. It is a leading cause of death among AIDS patients. People with AIDS commonly develop yeast infections of the esophagus (the tube that carries food to the stomach). This infection can cause severe pain when swallowing, resulting in weight loss and dehydration (excessive loss of water from the body).

People with AIDS often develop a form of cancer called Kaposi’s sarcoma. This cancer usually arises in the skin. It causes tumors that look like bruises. Kaposi’s sarcoma is rare in healthy people and usually grows slowly. But in people with AIDS, the tumors grow quickly and spread. AIDS patients can also develop tuberculosis or an eye infection called cytomegalovirus retinitis.

It may take from 2 to 15 years after infection with HIV for a person to develop AIDS. For children born with HIV infection, the interval is usually much shorter. Doctors have discovered that 4 to 7 percent of HIV-infected people do not develop any symptoms or opportunistic infections over many years, even without treatment. Medical professionals call such individuals long-term nonprogressors. A small percentage of people with HIV go 20 years without developing AIDS.

Medical treatment can delay the development of AIDS in several ways. It can inhibit the growth of HIV, preserve the immune system, and delay the onset of opportunistic infections. However, an infected person with or without symptoms can still transmit the virus to another person. Infection with HIV appears to be permanent in all who become infected.

How HIV is transmitted

The most common means of infection with HIV is sexual intercourse with an infected person. All forms of sexual intercourse can transmit HIV. In the United States, sexual transmission of HIV has occurred mainly among gay and bisexual men. But it also does occur among heterosexual men and women.

HIV can also be transmitted through exposure to infected blood. People can be exposed to infected blood in several ways. People who inject drugs can become exposed if they share unsterilized needles, syringes, or equipment used to prepare drugs for injection. Transfusion and transplant recipients and people with hemophilia can also contract the virus from the blood, tissues, or organs of infected donors. However, the screening and testing of donated blood, tissues, and organs has virtually eliminated this hazard. Health-care workers can come into direct contact with infected blood through injury with a needle or other sharp instrument used in treating HIV-infected patients. In a few instances, patients became infected after receiving treatment from an HIV-infected dentist or surgeon.

An infected pregnant woman can transmit HIV to her unborn child before and during the delivery, even if the woman shows no symptoms. An HIV-infected mother may also pass HIV to her baby through breast-feeding.

Medical care

Medical care for HIV and AIDS includes diagnosing and treating the illness. It also includes preventing the spread of HIV infection.

Diagnosis.

Tests for detecting evidence of HIV-1 in the blood became widely available in 1985. Tests for detecting HIV-2 in the blood became widely available in 1992. Both blood tests identify antibodies to the HIV virus. Antibodies are proteins produced by certain white blood cells in response to viruses or other invaders that enter the body. The presence of antibodies to HIV indicates infection with the virus. There is also an oral test for HIV-1 antibodies in mouth fluids.

Other tests directly measure the amount of HIV in the blood. These tests enable doctors to measure a patient’s response to treatment. They also help to predict the patient’s future health and estimated survival time. In 1996, the first home tests for HIV infection became available. People send in by mail a card holding a dried spot of their blood. Using an identification number, they can learn the results confidentially by telephone.

All HIV-infected patients should have their health closely monitored by a physician. They should receive periodic blood tests to measure the levels of virus and of CD4 cells in the blood.

Treatments.

Researchers have developed several treatments for HIV infection and AIDS. But they have yet to find a cure. Ever since the identification of HIV, scientists have worked to understand how it infects and damages human cells. In one important discovery, scientists learned that HIV reproduces using an enzyme called reverse transcriptase. This enzyme is not normally found in cells. Scientists therefore focused on developing drugs that block its action. These efforts led to development of a class of drugs called reverse transcriptase inhibitors. The first of these drugs, called zidovudine or AZT, was licensed in the United States in 1987.

AZT and other reverse transcriptase inhibitors sometimes produce harmful side effects. These side effects include anemia severe enough to require blood transfusions. HIV also develops resistance to these drugs. To improve the drugs’ effectiveness, doctors combine them and vary the order in which they are given.

In 1995 and 1996, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the first three of a class of drugs called protease inhibitors for treating HIV. These drugs block the action of protease, another HIV enzyme not found in healthy human cells. HIV uses protease at a later stage in its reproduction than it does reverse transcriptase. The first three protease inhibitors were indinavir, ritonavir, and saquinavir.

With the development of protease inhibitors, doctors began to combine them with other antiviral drugs. Studies showed that some antiviral drug combinations could decrease HIV in the blood to undetectable levels. At first, this kind of “drug cocktail” included several drugs taken at different times of the day for an indefinite period. But in 2006, the FDA approved the first single-dose combination pill. This combined therapy was originally called Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy (HAART). Today, it is more commonly known as Antiretroviral Therapy (ART). ART helps people with HIV to live normal lives. It also reduces HIV in the blood to such low levels that transmission becomes extremely difficult. It therefore serves to both treat the disease and prevent its spread. In 2021, the FDA approved a new type of ART, given to patients by injection. The injection is an extended-release therapy, which means that treatment is only needed once per month.

In the early 2000’s, researchers developed the first integrase inhibitors, which block yet other stages in the reproduction of HIV. They also developed fusion inhibitors and CCR5 antagonists. These drugs work by blocking HIV from entering human cells.

As a result of the various types of drug developments, by the early 2020’s, many doctors considered HIV to be a chronic, manageable condition. But HIV may still develop resistance to drugs. In addition, scientists have found that HIV persists inside CD4 cells. Even when the virus is managed, patients remain infected with HIV, and those who stop treatment will eventually develop AIDS.

Doctors also work with AIDS patients to prevent and treat opportunistic infections. PCP can be prevented with antibiotics. Physicians use chemotherapy and biological substances called interferons to treat Kaposi’s sarcoma (see Chemotherapy; Interferon). They believe that any eventual cure for AIDS must not only stop the growth of the virus but also prevent opportunistic illnesses and restore normal immune function.

Prevention.

To prevent HIV infection, a person must avoid sexual contact with anyone who is or might be infected with the virus. The most effective strategies are to refrain from all sexual intimacy or to restrict intimacy to one uninfected person. Health authorities recommend that a condom be used every time sexual intercourse occurs with a person who has HIV or whose infection status is unknown. Drug users should seek help to stop taking drugs. They should never share hypodermic needles, syringes, or other injection equipment.

Since 1985, health officials have used tests that detect the presence of HIV-1 to screen all donated blood and tissue products to ensure the safety of transfusions. Screening for HIV-2 began in 1992.

In 1994, researchers showed that AZT reduced the risk of transmission from an HIV-infected mother to her baby. Since then, other drugs have been developed. Today, physicians routinely administer a combination of three antiretroviral drugs to HIV-infected women during pregnancy and labor and to their newborn babies. Doctors advise HIV-infected women not to breast-feed.

In the late 1980’s, researchers found evidence that male circumcision might help protect against the transmission of HIV (see Circumcision). By 2006, controlled trials in Africa indicated that male circumcision reduced the risk of HIV-1 transmission from females to males. Researchers did not find circumcision to have similar protective value for transmission from male to female or from male to male. In 2007, the World Health Organization recommended male circumcision as an effective intervention against HIV transmission.

Public health agencies have provided guidelines for preventing the transmission of HIV in health care settings. Physicians, dentists, and other health care workers wear gloves, masks, and other protective clothing during many examinations and procedures.

The search for a vaccine against HIV has proven difficult. HIV is a complicated virus that mutates (changes) rapidly, making traditional vaccines impossible to use. Nonetheless, researchers continue working to develop safe, effective, and economical vaccines against HIV infection. However, even if HIV transmission ended, AIDS cases would still occur because millions of people are already infected with the virus. As a result, scientists are also working to develop vaccines that would boost the immune systems of HIV-infected people.

Social issues

AIDS is a relatively new life-threatening disease. At first, it mainly affected young adults. In the public imagination, the disease soon became associated with risky sexual behavior and with drug abuse. For all these reasons, efforts to address AIDS or to prevent the spread of HIV have at times faced unique social challenges.

Education

about AIDS, both in schools and in the community, has become the chief means of preventing infection. Some schools have established health clinics that distribute condoms to students. However, some people oppose even classroom discussion of condom use. They believe that such discussion implies acceptance of sexual intimacy outside of marriage.

Other important approaches to reducing transmission include preventing drug use and educating drug users about HIV. Some communities have launched sex education and needle-exchange programs among drug users. Needle-exchange programs provide sterilized needles for those who cannot or will not stop injecting drugs. But many people have criticized such programs for their implied acceptance of drug abuse.

In the United States, federal, state, and local governments have provided funds for AIDS education, treatment, and research. Public health clinics offer counseling and HIV-antibody testing to people who have symptoms or are at risk of infection. In addition, these clinics may privately and confidentially notify an infected person’s sexual or needle-sharing partners of their risk. Once notified, such partners too can receive preventive counseling, testing, and medical services.

Public awareness.

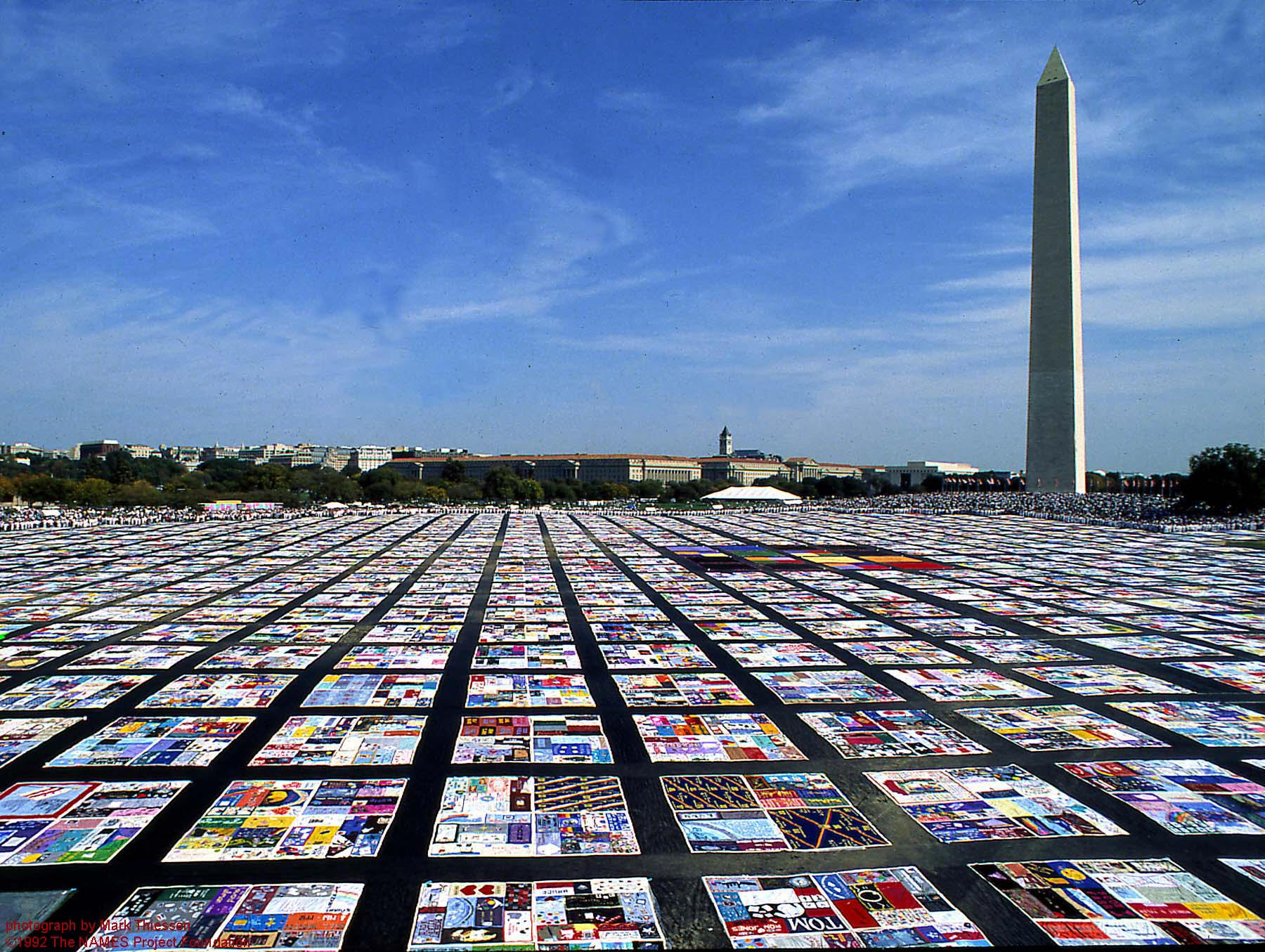

Many individuals and organizations have worked to increase public awareness of AIDS. The most active organizations include community-based groups and the American Red Cross. They hope that greater awareness will generate more compassion and support for people living with AIDS. They also hope to ensure adequate funding for HIV prevention, treatment, and research. One prominent project bringing attention to the crisis is the AIDS Memorial Quilt. Begun by the NAMES Project Foundation in 1987, the quilt consists of thousands of individually designed panels. The panels memorialize people who died of AIDS. The quilt has been displayed throughout the world.

Celebrities have also helped raise public consciousness of AIDS. Many well-known entertainers and athletes have participated in education and fund-raising efforts. The epidemic also has gained attention as a result of well-known people becoming infected with HIV or dying from AIDS. They include actor Rock Hudson, who died of AIDS in 1985, and tennis champion Arthur Ashe, who died in 1993. Basketball star Magic Johnson announced he was infected with HIV in 1991. Olympic diver Greg Louganis announced his infection in 1995.

Beginning in 1988, the United Nations has designated December 1 each year as World AIDS Day. On this day, public agencies and schools around the world sponsor education and prevention programs. Many people wear a red ribbon to show support for people with AIDS.

Discrimination.

Poor understanding of HIV has at times stoked public fears, leading many people with the virus to suffer unjustly. Some of the infected have lost or been denied jobs or housing. Others have been denied medical care and health insurance. Many children with AIDS were initially barred from attending school or playing on sports teams. To prevent discrimination, people with HIV and AIDS are often included under laws protecting the rights of people with disabilities. The United States government and some states have also strengthened laws safeguarding the confidentiality of medical records relating to HIV infection and AIDS.

Preventing discrimination against people with HIV is not only just—it also protects public health. When people can live without fear of discrimination, they are more likely to seek counseling and treatment. In many cases, such measures lead to earlier diagnosis and a reduction in risky behavior.

Providing medical care

for the hundreds of thousands of people with HIV and those with AIDS is expensive. Planning and paying for this care consumes considerable resources. Some of the burdens may be reduced through prevention efforts and by finding less expensive alternatives to hospital care. Such alternatives may include expanded home care services and hospice care. Hospices are places that care for people who are dying.

Antiviral drugs are effective in prolonging the lives of people with HIV. But the cost of the drugs exceeds what nearly any individual can pay. Patients in developing nations in particular often lack sufficient access to medical care and cannot afford these medications. Experts view this issue, as well as the public health impact of AIDS itself, as a major challenge to social and economic progress in developing nations. Even in developed nations, state funds for antiviral drugs can be limited.

AIDS around the world

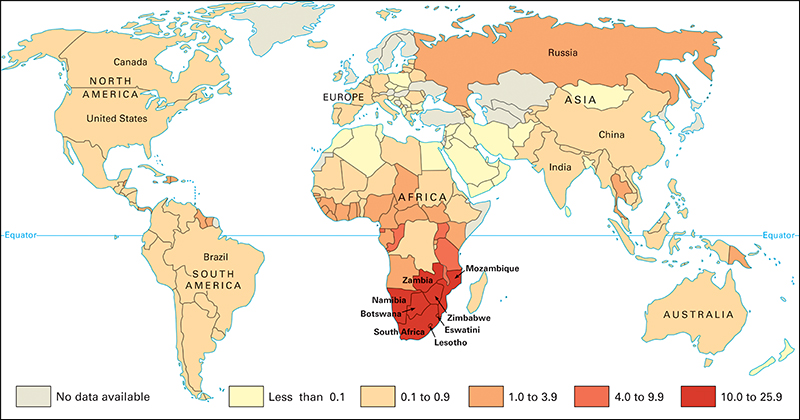

AIDS occurs in every nation. In areas such as Africa south of the Sahara, Southeast Asia, and India, HIV transmission has occurred mostly among heterosexual men and women, particularly young adults and teens. Many developing nations carry enormous burdens of HIV infection. For example, the United Nations reports that in some parts of Africa, the infection rate may reach over 30 percent in some urban areas. The huge number of young adults dying of AIDS in Africa south of the Sahara has decreased overall life expectancy across the continent. A growing number of people have also become infected in countries with increasing drug use, such as Russia, China, and the nations of central Europe.

Since 1986, the international health community has worked to coordinate the global fight against HIV and AIDS. The World Health Organization’s Global AIDS Programme formed the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) in 1996. Since that time, UNAIDS has worked with other international partners to coordinate the global fight against HIV and AIDS.

History

Scientists do not know for certain exactly how, when, or where the AIDS virus evolved and first infected people. Researchers have shown that HIV-1 and HIV-2 are more closely related to viruses that infect monkeys and apes than to each other. They believe HIV evolved from viruses that originally infected primates (monkeys and apes) in Africa. The virus was somehow transmitted to people.

In 1999, U.S. researchers found evidence that HIV-1 most likely originated in a population of chimpanzees in west Africa. Further genetic studies in 2006 supported this theory. The virus appears to have been transmitted to people who hunted, butchered, and consumed the chimpanzees for food. Later studies suggest HIV probably spread to humans between 1884 and 1924. Transportation routes created by colonial powers brought HIV-infected people to the growing cities of central Africa, facilitating the spread of the virus. HIV was transmitted between sexual partners and from mothers to babies.

Scientists believe HIV infection became widespread after major social changes in Africa during the 1960’s and 1970’s. Large numbers of people moved from rural areas to cities. This shift caused growth in crowding, unemployment, and prostitution, which in turn increased cases of sexually transmitted infections, including HIV. HIV may have been introduced into industrialized nations several times before it became widespread.

AIDS was first identified as a disease by physicians in California and in New York City, New York, in 1981. Doctors recognized the condition as something new because all the patients were previously healthy, young gay men. They sought medical care because they were suffering from otherwise rare forms of cancer and pneumonia. In 1982, the disease was named AIDS. Scientists soon determined that AIDS occurred when the immune system became damaged. They also learned that the agent that caused the damage was spread through sexual contact, shared drug needles, and infected blood transfusions.

After researchers isolated HIV as the cause of AIDS in 1983 and 1984, they developed tests to detect HIV infection. Scientists have used these and other tests to analyze stored tissues from several people who died from the late 1950’s through the 1970’s. Scientists have concluded that some of these people died from AIDS.

Cases of HIV infection reported worldwide rose dramatically during the 1980’s and 1990’s. By 2010, experts estimated that about 33 million people were living with HIV infection or AIDS throughout the world. More than 35 million people had died since the epidemic’s beginning. But scientists have observed that the number of newly infected people has declined since the late 1990’s, largely due to stabilizing rates of infection in Africa.

In the United States, about 50,000 people are infected with HIV each year. This rate has remained relatively steady since the late 1990’s. In the early part of the epidemic, new infections occurred primarily among gay and bisexual men. In the late 1980’s and 1990’s, however, more women, children, and drug users became infected. Minority groups have suffered a disproportionately high rate of infection from the beginning of the epidemic. Today, African Americans make up the majority of new cases of HIV in the United States.

Some success has been achieved in controlling the spread of HIV. In the United States, for example, among gay and bisexual men, HIV has spread more slowly than it did in the early 1980’s. These improvements result almost entirely from community-based education about AIDS prevention and the ensuing changes in sexual behavior. As a result of education, many gay and bisexual men report fewer sexual partners and increased use of condoms. HIV blood tests, which became available in 1985, caused a gradual decline in transfusion-related cases in the late 1980’s. The rate of infection in other groups rose, however, during the 1980’s and 1990’s. These groups include heterosexual men and women and people who inject drugs.

During the mid-to-late 1990’s, advances in HIV treatment slowed the progression of the infection into AIDS. This slowing has led to dramatic decreases in the number of people living with AIDS in the United States. In 2010, the United States released the first National HIV/AIDS Strategy (NHAS). This comprehensive and coordinated plan was designed to reduce the prevalence of HIV in the country. It was updated in 2015. In 2021, the United States replaced the NHAS with the HIV National Strategic Plan (HIV Plan). The goal of the HIV Plan is to reduce nationwide HIV infections by 90 percent by 2030.

In 2012, the FDA approved the first combination of drugs to help prevent the transmission of HIV between people. Such medications are called pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). In research studies, taking PrEP lowered a person’s risk of contracting HIV by as much as 90 percent. But the high cost of PrEP drugs and the fact that they must be taken daily have limited their impact on infection rates.

In 2021, the FDA approved a new treatment for HIV, given to patients by injection. The injection is a combination of the drugs cabotegravir and rilpivirine. Only one injection is needed per month. Doctors hope this new option will help more patients get treatment.