Colonial life in Australia and New Zealand is the story of the men, women, and children who left Europe and settled in Australia and New Zealand in the late 1700’s and early 1800’s. During this period, large numbers of people, most of them British, undertook one of the longest-distance mass migrations in history. For example, between 1851 and 1860, nearly 500,000 people sailed from the United Kingdom to Australia, a distance of more than 10,000 miles (16,000 kilometers).

Most of these early colonists (also referred to as settlers or immigrants) encountered an unfamiliar, often harsh, environment. Much of Australia consisted of desert or dry grassland. The colonists attempted to preserve the cultural traditions of their homeland. However, the new environment and altered social, economic, and political circumstances forced them to forge new societies. The lives that the colonists led laid the foundations for the modern states of Australia and New Zealand.

During this period, Australia and New Zealand did not yet exist as countries. Australia consisted of a number of colonies—New South Wales, Van Diemen’s Land (later called Tasmania), Victoria (from 1851), South Australia, Western Australia (originally known as the Swan River Colony), and Queensland (from 1859). New Zealand was made up of a number of separate provinces.

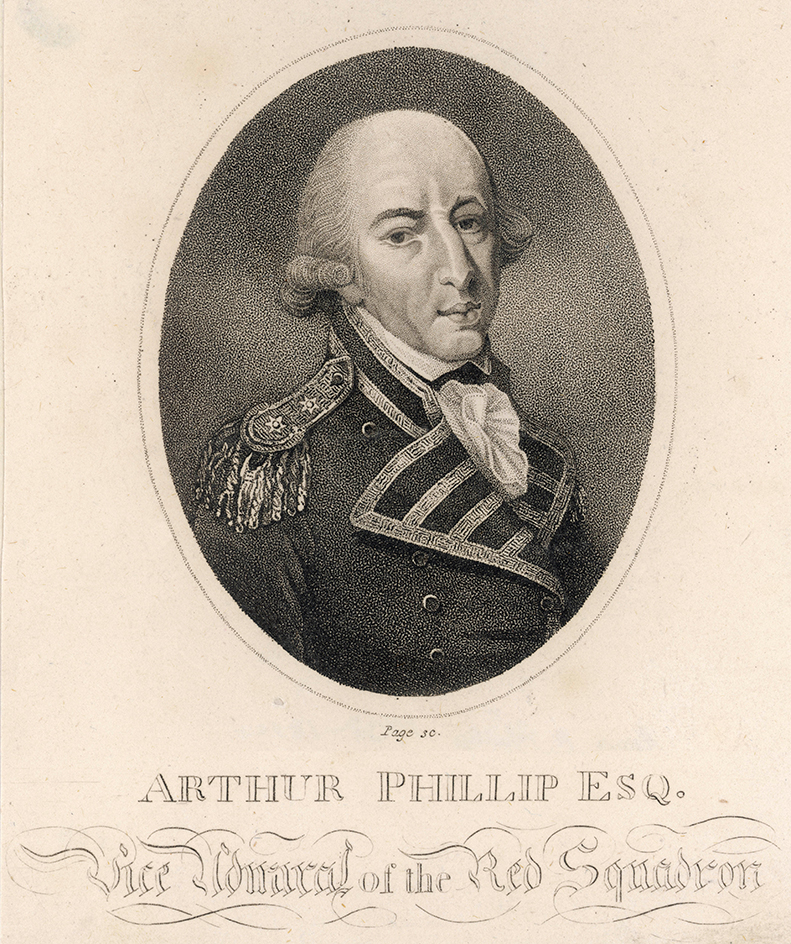

The first European settlers in Australia were convicts. In 1788, a group of British ships called the First Fleet reached Australia with convicts and their guards to establish a prison colony there. Arthur Phillip, an officer of the Royal Navy, was the fleet’s commander and the first governor of the colony of New South Wales. Phillip established a settlement at Sydney Cove on the southeast coast of Australia. The convicts built themselves housing and established families, businesses, and farms.

Many free immigrants also came to Australia, attracted by free land grants and cheap convict labor. By 1828, free people outnumbered convicts. In the 1830’s, the British government began to encourage free immigration. Under a system called assisted migration, the government provided money raised from the sale of land to support new settlers. The British government particularly sought skilled workers and single women as immigrants. This article will deal primarily with free colonists. For information on Australia’s convict settlers, see the article Convicts in Australia.

This article will focus on the period from the first European settlement until about 1855, when many of the colonies had a change of government. At about that time, many colonies switched from direct rule by the United Kingdom to electing their own parliaments and administering their own finances. The article will describe the arrival of European colonists in Australia and New Zealand and their relations with the original inhabitants of those lands, the Aboriginal peoples of Australia and New Zealand’s Māori people. The article will examine the colonists’ lives in that early period, including their buildings, clothing, food, transportation, communication, employment, law enforcement, health, religion, education, and recreation.

The arrival of European colonists

At first, only small groups of European settlers came to Australia and New Zealand. Among the first free settlers in New South Wales, Australia, were a party of two families and three unmarried men who arrived in the ship Bellona in 1793. The British government gave them title to an area of land just outside Sydney, which they named Liberty Plains. Most of the early European settlers of South Australia and New Zealand sailed on voyages organized by Edward Gibbon Wakefield, a British colonial reformer. Civilian settlement in Queensland in northeastern Australia began in 1840 in the Darling Downs region. Brisbane, now the capital of Queensland, opened to civilian settlement in 1842.

In Van Diemen’s Land, small groups of pioneers landed soon after Governor David Collins founded Hobart in 1804. The first settlers arrived at Fremantle in the Swan River Colony in 1829 on the ship Parmelia. But lack of water and other conditions kept the settlers in the southwestern corner of what is now Western Australia for many years. Similar problems confined most of the early colonists of South Australia to the coastal areas. However, several hundred German immigrants settled in the Barossa Valley in South Australia and helped establish the colony’s wine industry.

European settlers came to New Zealand later than Australia. About 2,000 missionaries, traders, sealers, and whalers had settled along the New Zealand coast before 1840. In that year, three ships carrying mostly migrant farmers landed at Wellington, in the southern part of North Island. In the next few years, settlements sprang up at Canterbury, Nelson, New Plymouth, Otago, and Wanganui.

Immigrants arriving in Australia and New Zealand found that their world had been literally turned upside down. North was where south should have been. They celebrated Christmas in the heat of summer instead of the chill of winter. Unknown stars filled the night sky. The new lands were covered in unfamiliar plants and inhabited by strange animals and birds. The strange new land brought feelings of homesickness. Most migrants never expected to see their old homes or friends again. But in time, many came to love their new home.

Relations with the original inhabitants

Relations between early settlers and Indigenous (native) peoples varied greatly between Australia and New Zealand. There are several reasons for this variation. New Zealand’s Māori had a social structure divided into classes. Paramount chiefs formed the highest class, followed by lesser chiefs. The middle of the class structure consisted of commoners, and at the bottom were enslaved people. Māori generally welcomed early settlers in New Zealand and incorporated them into Māori social structure. The Aboriginal peoples of Australia, on the other hand, lived in a society where all members had relatively equal social standing. Māori usually resided in permanent settlements and practiced agriculture. Australia’s Aboriginal people, however, did not have any form of farming that the Europeans recognized. Their economy was based on hunting, gathering, and fishing. They continuously moved their camps. Māori quickly adopted and adapted European ways of life. The Aboriginal peoples of Australia did not. These differences had a significant effect upon relations between the colonists and Indigenous people.

The early explorers to Australia developed a false perception that Aboriginal people were primitive, timid, few in number, and living in scattered tribes. The explorers thought that the Aboriginal peoples wandered aimlessly across the landscape with no concept of landownership. Many Europeans assumed that, when they came to occupy the continent, the Indigenous people would surrender their territory peacefully. If Aboriginal people did resist, Europeans thought, the superiority of British technology and weapons would soon dispel any resistance.

Initial encounters between Aboriginal peoples and the First Fleet, the settlers who arrived in 1788, were friendly. However, relations with Indigenous people soon soured, and a cycle of hostility developed. Misunderstandings, thefts, and acts of violence followed.

Aboriginal society was divided into small groups based on kinship, which meant that the people did not engage Europeans in mass battles. Instead, they drew upon their knowledge of their country, especially the remote countryside called the bush. Aboriginal people had superior bushcraft—that is, knowledge of how to get food and shelter, and how to find their way in the bush. Aboriginal people employed raiding tactics, attacking isolated stockmen and pioneering families. Colonists lived with the threat of physical attack. Some of them were killed. Aboriginal people looted their property and slaughtered their livestock. Frontier settlers lived in fear and insecurity for much of the first half of the 1800’s.

In turn, the Europeans responded to Aboriginal attacks with violent raids of their own. In 1838, for example, cattle workers murdered about 28 Aboriginal men, women, and children at Myall Creek in New South Wales.

In the end, the Aboriginal people’s spears were no match for European firearms, especially after the introduction of repeating rifles (rifles that fire several shots without the need for reloading). Disease and other factors, such as malnutrition, also took their toll, and Aboriginal populations fell. In response, Aboriginal peoples sought new means to live with the invaders. One strategy was to become part of the sheepherding and cattle-raising industry. The success of this industry, especially in remote areas, was due to the efforts of Aboriginal people as stockworkers, shepherds, shearers, and household servants.

In New Zealand, the early interactions between colonists and Māori were peaceful, though uneasy at times. The relationship was based upon coexistence and mutually beneficial trade. Māori initially welcomed the colonists and encouraged the immigration of new settlers. Individual Māori groups effectively sponsored early European settlements, particularly in the northern parts of New Zealand. Māori saw benefits in European culture and sought to acquire new goods and fresh knowledge.

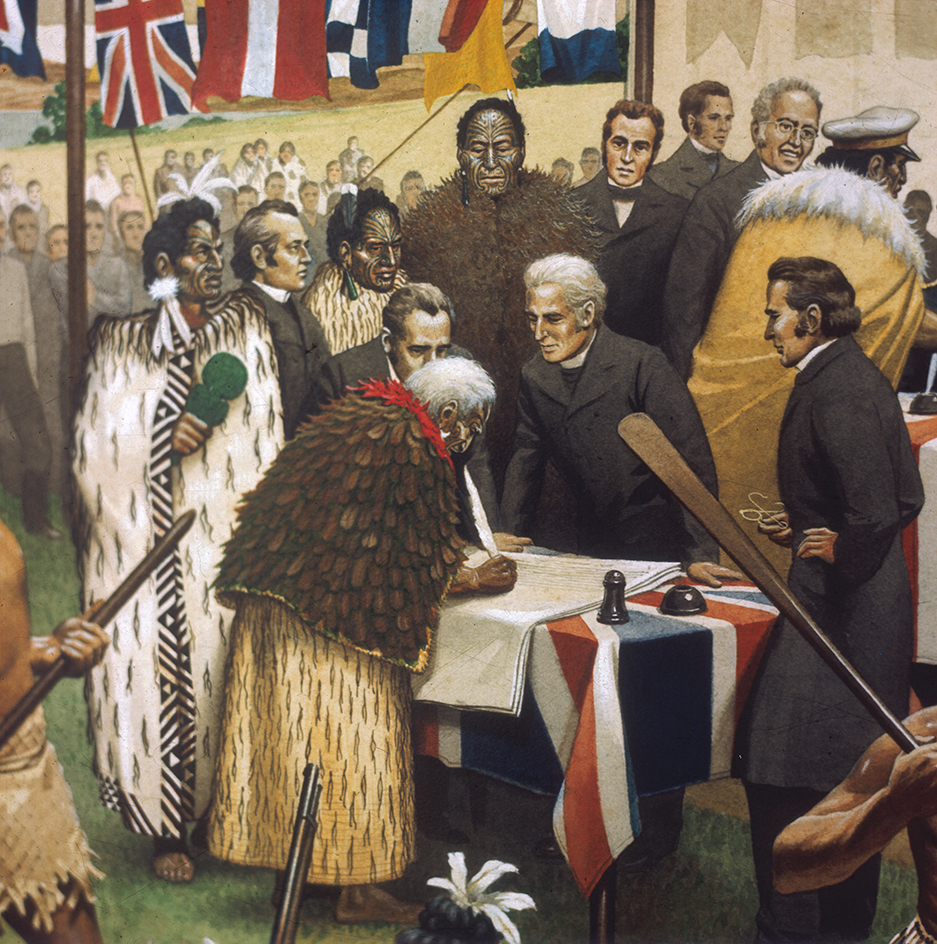

Many early settlements only survived because of the food and other provisions supplied by their Māori hosts. Importantly, Māori controlled where the Europeans could settle. In the period up to 1840, the numbers of colonists were small and the balance of power favored Māori. They were skillful warriors who had adopted European weaponry. The signing of the Treaty of Waitangi in 1839 shifted the balance toward the British migrants, who soon began to arrive in greater numbers. This shift altered the previously friendly relationship and set it on a course toward conflict. By the mid-1840’s, relations between Māori and Pākehā (the Māori term for non-Māori) deteriorated. A disturbance known as the Northern War (1845-1846) broke out. It was the first skirmish before a series of major conflicts known as the New Zealand Wars (1860-1872).

Buildings and houses

Most homes and public buildings resembled the buildings the colonists had left behind in the United Kingdom. But the colonists also used local building materials and adapted their buildings to the climate. As a result, uniquely colonial building styles developed. The British influence was particularly marked in the grand homes of wealthy colonists.

When a pioneer family arrived where they intended to settle, they could not spare enough time to build a permanent house right away. Instead, they put up a tent or other temporary shelter. Later, the family would replace their makeshift shelter with a more substantial home. Acquiring a home was important to the colonists. Home ownership demonstrated independence and respectability, important values in colonial society.

The first house to be built in Australia was for the first governor, Arthur Phillip. It was a two-story building of stone and brick, divided into eight rooms. It was constructed within 18 months of the first settlers arriving in Australia. The house was a model of Georgian architecture, the dominant architectural style of that time. The style was characterized by simplicity and restraint, with rectangular floorplans and symmetrical facades.

Accounts from the early colonial period describe most people living in single-story, two-room huts with thatched roofs. The walls were made of wattle-and-daub, a basketwork of thin branches (wattle) plastered with mud (daub). Many of these dwellings had floors made of hard-pressed earth, or timber laid directly on the ground. In the early period, only the wealthy could afford window glass.

More prosperous colonists lived in cottages, which had window glass, roofs made of wooden shingles, a chimney of sandstock (handmade) bricks, and a veranda. Wide verandas became common features of early colonial homes because they cooled and shaded the house, providing relief from Australia’s hot climate. Colonists covered their cottages with a paintlike coating called whitewash and built wooden fences around their homes.

Early colonists also used other construction techniques. Among Irish settlers and in areas where timber was scarce, the colonists cut sod squares from grassy ground to use as a building material. They also built houses using adobe (sun-dried mud bricks) and pisé (earth rammed hard in a timber form).

In New Zealand, early colonists incorporated several Māori techniques. For example, they used vertically arranged ponga (tree fern) logs for walls.

Clothing

The colonists wore British styles of clothing. In general, the clothing was too hot and too tight for the climate, but the colonists made some changes for practicality and comfort. One early local adaptation to the environment was the cabbage-tree hat. This head covering was a wide-brimmed hat made of finely woven strips of leaves from the cabbage-tree palm, a native palm in both Australia and New Zealand. Cabbage-tree hats first appeared in the late 1800’s and remained popular for much of the next century. For women, shawls and parasols (umbrellas) became popular because they provided protection against the hot sun.

Initially, settlers had to make do with the clothing that they had brought with them. Little new clothing or cloth arrived from the United Kingdom. All classes suffered from shortages of clothing, even as late as the 1820’s. In particular, there was a great shortage of footwear. Many colonists, especially children, young women, and the poor, went barefoot much of the time. As their clothing wore out, people became ragged. In the first decade of settlement, clothing theft was common.

Many male settlers dressed like farmworkers in the United Kingdom, wearing smocks or frocks (a type of long coat), leather aprons, and loose-sleeved shirts. Later, working men also adopted flannel shirts and trousers made of a strong, thick cotton fabric called moleskin. Many men also wore long boots and duck trousers, made of sturdy cotton called duck. The wearing of colorful silk neckerchiefs also became fashionable. For special occasions, men added cloth caps, cotton jackets, and fancy waistcoats.

Colonial women made most of the family’s clothes, sewing them by hand. The women also were generally responsible for repairing torn and worn items. In addition, women did the work of washing clothes, often in copper vats in the open air, as well as the ironing.

Food

The First Fleet brought with them plants and animals from England, including cattle, ducks, geese, goats, pigs, rabbits, sheep, and turkeys. The few cows that survived the voyage quickly escaped and were not found until several years later. The rabbits died, as did many of the sheep and goats. But in both Australia and New Zealand, pigs and poultry thrived.

The British government forecast that the first European settlers of Australia would become self-sufficient in food production within three years. The government based this forecast partly on early reports that the land seemed suitable for farming. However, many early settlers arrived without the necessary tools and farming skills to grow the food they needed. In addition, they knew little about local conditions.

In both Australia and New Zealand, early colonists failed to establish successful farms or grow enough food. Early crops failed, and fresh supplies did not arrive. Colonial officials rationed the provisions that the colonists had brought with them. There was a great shortage of food. The colonists’ diet lacked dairy products, vegetables, and important nutrients and vitamins. Major outbreaks of scurvy, an illness caused by a deficiency of vitamin C, occurred in New South Wales during what are known as the “Hungry Years,” 1788 to 1792.

The colonists were forced to experiment with local foods to fight hunger and malnutrition. By trial and error, and by observing Aboriginal people, they discovered which plants were edible. The colonists incorporated Indigenous food, which they called bush tucker, into their diet. Colonists went fishing, gathered shellfish, and hunted such wild animals as kangaroos and wallabies. Settlers also supplemented their basic diet with leaf buds called “cabbage” from the cabbage-tree palm and tried various native beans, berries, and herbs. They also learned how to prepare other foods, such as the seed of the burrawong palm, which was poisonous if not first soaked and then roasted.

In New Zealand, Māori suppliers met some of the demand for food. Māori had seen the potential of European plants and animals, and incorporated them into their agricultural practices. The new crops flourished in the rich New Zealand soils, and Māori used the surplus in trade with Europeans.

Māori supplied apples, cabbages, corn, grapes, melons, onions, peaches, potatoes, pumpkins, sweet potatoes, and quinces. They also provided flour processed in Māori mills as well as chickens, fish, geese, goats, and turkeys.

Gradually, the colonists began to meet their own food requirements. They cultivated vegetable gardens where they grew cabbages, green beans, kidney beans, potatoes, and turnips. Fruits grown by the colonists included apricots, nectarines, oranges, peaches, and even watermelons. Peaches were so plentiful in early Sydney that they were fed to pigs.

Success in growing wheat was especially important. In keeping with their British heritage, the settlers preferred wheat flour to make their bread. Cornmeal was made into a dish called hominy.

Meat was plentiful and cheap, and the colonists ate large amounts of it at every meal. One of the slogans used to promote migration to the colonies was “Meat Three Times a Day.” The abundance of meat resulted from the success of livestock raising in these countries and the fact that, until the introduction of refrigeration in the early 1880’s, there was no export market for meat.

Tea was the principal drink of the colonies. Drinking tea had the health advantage of ensuring that water was boiled, lessening the risk of illness from water-borne bacteria.

The colonists did most cooking using pots and frying pans over an open fire, whether at campsites or in cottages. A basic food was damper, dough prepared from flour and water and baked in the ashes of a fire. People boiled water for tea in a quart pot called a billy can. Cooks prepared many meals in a Dutch oven or camp oven, a round cast-iron pot with legs and a handle that allowed it to either sit in the embers or hang above a fire. By the mid-1800’s, a device called the colonial oven had also become popular. This cooking innovation was a simple cast-iron box with a door that sat in a fireplace. Cast-iron cooking ranges became available in about the 1850’s.

Transportation

Transportation in colonial Australia and New Zealand was slow and difficult. Vast distances separated the first towns. Extremes of heat and cold, drought and rainfall, together with deep valleys, high mountain ranges, and vast deserts, created many challenges. Bridging the distance among remote early settlements was vital for the survival and prosperity of any colony. Effective transportation lessened the sense of isolation, facilitated communication and the distribution of news, and made possible the regular exchange of goods and services.

In both countries, rivers and coastal shipping played a fundamental role at first. With the exception of Adelaide, Australia, all the early centers of settlement were founded on rivers or sea inlets. As early as 1789, Governor Phillip had a small boat, the Rose Hill Packet, built to connect the settlements of Sydney and Parramatta (originally called Rose Hill). Boatbuilding was one of the first commercial occupations and an important industry throughout the colonial era. At first there was a limit of 14 feet (4.3 meters) on the length that a boat could be built without the permission of the governor. The purpose of this regulation was to prevent convicts escaping by sea. By the end of the 1700’s, however, larger boats were being built to improve the transportation of people and goods.

In the early 1800’s, several boatyards began to build ships in Van Diemen’s Land. This island colony was blessed with many trees, such as blue gum, huon pine, and celery top pine, that produced excellent shipbuilding timbers. Shipyards also sprang up in and around Melbourne, in what was to be the state of Victoria, at the end of the 1830’s. By the 1850’s, shipyards at Brisbane in Queensland and at Port Adelaide in South Australia built large ships. Shipping increased until it connected all the centers of settlements in a single trading network.

Beginning in the early 1830’s, there was a gradual change from sailing ships to steamships. The first steamship built in Australia was the paddle steamer Surprise, launched at Sydney in 1831. Steam-powered vessels had an advantage over sail because they did not depend on coastal winds. Steamships also had better ability to navigate shallow river mouths and inland rivers. River shipping gave access to large areas of new land and played an important role in supporting European settlement.

The building of roads opened the interior to settlement. Governor Lachlan Macquarie, who arrived in New South Wales in 1810, began an ambitious program of building new roads and bridges. Under his direction, a turnpike road, whose users paid a toll for its maintenance, opened between Sydney and Parramatta in 1811.

Macquarie also built carriage roads, fit for wheeled vehicles. One of the most important carriage roads crossed the steep Blue Mountains, linking Sydney with the region where the frontier town of Bathurst was soon established. Completed in 1815, this 100-mile (160-kilometer) road was one of the most important roads ever built in Australia. It allowed colonists access to the vast grazing lands on the western side of the Great Dividing Range.

Another great engineering feat during the early colonial period was the construction of the Great North Road, completed in the mid-1830’s. The Great North Road assisted in opening up the fertile lands of the Hunter Valley and areas farther north to colonists.

In New Zealand, the construction of roads linking settlements began in the mid-1840’s. Governor George Grey employed Māori as roadbuilders. Some of the best early roads were constructed under military direction, such as the Great South Road from Auckland.

Horses and bullocks (oxen) were some of the earliest animals imported to Australia and New Zealand. At the beginning, there were few horses. Only seven survived the First Fleet voyage. All the horses were claimed for government use. Colonists, both rich and poor, traveled on foot and regularly walked vast distances. By 1810, there were over 1,100 horses in the colony, and thereafter the numbers multiplied quickly. Some were ridden as saddle horses, and others pulled sulkies (light two-wheeled carriages) and four-wheeled buggies. Owning a saddle horse became an important status symbol in colonial Australia.

Teams of horses and bullocks pulled carts, wagons, and drays, low carts used to carry heavy loads. Local wagon makers manufactured all these different types of vehicles by 1800. Wagon makers based these vehicles upon European designs but modified them to meet the demands of the Australian setting. One difficulty with the heavier drays was that they had no effective means of braking. The lack of brakes could be a serious problem when descending a steep ridge or hill. Often the driver dragged a log behind the dray to slow it down.

Colonists used teams of bullocks to transport heavy loads. Although slower than horses, bullocks were strong, patient, and reliable. Their wooden yokes with chains were cheaper than the complex leather harnesses used by teams of horses. They did not require shoeing and could be left to forage on grass at the end of the day, whereas working horses needed expensive grain.

The usual team size was 6 to 10 animals. At first, bullocks were bred from ordinary domestic animals, but later they were crossed with water buffalo to improve their strength. As hardened roads became more common, teams of horses gradually replaced bullocks, being much faster on such surfaces.

Communication

Early settlers relied upon letters and newspapers to communicate the events of their world and their lives. Travelers passed letters and carried them for friends. Most colonists who wanted to send a letter “home” had to make personal arrangements with the captains of ships sailing back to the United Kingdom. Ship’s captains carried letters for a fee. Later, as settlers moved inland, horse or bullock carts carried messages.

As shipping services and roads improved, regular mail services developed. Within Australia, the first known regulations dealing with mail delivery were established in 1803. They set fees that boatmen could charge for delivering mail along the Parramatta River between Sydney and Parramatta. More regular collection and distribution of mail began in New South Wales in 1809, when Sydney’s first postmaster was appointed. By the 1850’s, postal services had developed in the other Australian colonies, and a postal network linked all of the colonies. The later settlement of New Zealand meant that official postal services did not begin there until the 1840’s.

Newspapers were an important part of colonial life. They kept colonists informed of both local and international news, and also ensured that the colonists learned about technological developments. Newspapers were passed from one person to another. The first newspaper in Australia was the Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, established in 1803. The Gazette was originally a weekly newssheet devoted to publishing government notices. It increasingly printed private notices and advertisements, shipping notices, law reports, agricultural extracts, moral and religious tracts, news from the United Kingdom, excerpts from literary works, and poems by local writers. In its early years, the Gazette sometimes had to suspend printing because of paper shortages.

The first newspaper to be published in New Zealand was the New Zealand Gazette in 1840. It soon had its title expanded to the New Zealand Gazette and Britannia Spectator, and then changed to the New Zealand Gazette and Wellington Spectator.

Employment

Colonists worked at a wide assortment of skilled, semiskilled, and unskilled occupations. Occupations associated with building employed a range of workers, including bricklayers, carpenters, masons, and painters. Cooks, gardeners, and maids staffed the houses of the wealthy. Women worked as barmaids, laundrywomen, and seamstresses. Men were employed as agricultural laborers, dairymen, fishermen, general laborers, sailors, shearers, shepherds, shop assistants, soldiers, and wharf workers. Men also engaged in professional occupations, working as doctors, lawyers, and ministers of religion. In addition, there were business owners, merchants, and shopkeepers.

The colonial economy employed large numbers of men to tend livestock as shepherds, shearers, and drovers. These men were paid for their labor not only in cash but also in rations, generally dispensed once a week, of meat, flour, sugar, and tea. Many shepherds tended their sheep alone without even the help of dogs or horses. Early cattle workers also lived under rugged conditions, particularly during the annual cattle musters (roundups) or when they moved their herds to market. During these periods, they lived and worked out in the open in all kinds of weather. Many cattle trails extended more than 1,000 miles (1,600 kilometers) across Australia. Good food and water supplies could be scarce.

Law and order

The early colonial justice systems and legal institutions, such as courts, police, and prisons, were based on those of England. The laws of the colonies were the British laws, until the colonies were granted powers to write their own legislation. Even then, the British government kept the right to reject any legislation.

The colonists took steps to modify the English system to meet the circumstances in which they found themselves. For example, in Australia, judicial officers called magistrates played a greater role and had more power than their counterparts in England. Powerful magistrates were necessary to maintain order over the population, which had many convicted criminals distributed unevenly over an extensive frontier.

In 1823, the New South Wales Act was passed in the United Kingdom. The act established a formal legislature in the colony for debating and passing local laws. The New South Wales Act also set the foundations for the legal system that was to operate throughout the Australian colonies for the remainder of the 1800’s. It established a Supreme Court and trial by jury. Colonial Supreme Courts sat in judgment over criminal cases and had extensive powers for dealing with a wide range of legal matters. In New Zealand, the Supreme Court was established in 1841.

A distinctive Australian type of outlaw, who represented a real threat to early colonists, was the bushranger. Originally bushrangers were convicts who had escaped and attempted to survive through robbery on the frontiers of settlement. Gangs of bushrangers robbed and terrorized frontier settlers in Van Diemen’s Land and in New South Wales.

Flogging was a common and official means of punishing offenders in early Australia. Stocks were used to hold persons accused of minor offenses until they could be tried and later were used to punish convicted offenders. For more serious offenses, culprits could be sentenced to hard labor in irons (chains) or imprisoned in a jail. The most serious offenses were punished by hanging.

From the early 1820’s until the 1850’s, British soldiers in the Military Mounted Police undertook much of the police work carried out in the eastern colonies. In New South Wales, a Horse Patrol was formed in 1825 from volunteers from various regiments. The Horse Patrol was established to deal with the growing numbers of bushrangers and with the resistance of Aboriginal peoples to the invasion of their lands.

Health

The early free settlers to Australia suffered from many ailments. Undetermined fevers were common in late winter and early spring, as were eye infections and skin rashes in summer. These ailments were particularly widespread among children. The young, old, and frail suffered most when epidemics, such as influenza, mumps, and whooping cough, raged through the colony. Most early townships lacked safe drinking water as well as adequate sewerage and waste disposal systems. Unsanitary conditions often led to outbreaks of water-borne diseases, such as dysentery and typhoid.

Dysentery was the most widespread and often fatal disease. Few escaped this illness upon arriving in New South Wales. Sydney’s sole source of water, the Tank Stream, was so polluted that dysentery was permanent in the area until the late 1790’s. Once steps were taken to prevent the pollution of the stream, cases of dysentery in the population declined.

Most families tended the sick in their own homes. Either a patient would visit a doctor, or more commonly a doctor would visit the patient.

Most people dreaded hospitals. Hospitals were unsanitary institutions where dysentery, lice, typhus, and other infections were common. The government operated all the early hospitals, known as general hospitals because they treated a wide range of ailments. They charged patients a fee for their use. Hospitals had doctors who prescribed treatment, but they lacked a trained medical staff. The day-to-day care of patients was the responsibility of servants, family members, and healthier patients.

Religion

The first settlers in Australia and New Zealand belonged to four major denominations of Christianity—the Church of England (Anglicans), the Church of Scotland (Presbyterians), the Roman Catholic Church, and the Wesleyans (Methodists). English colonists were predominantly Anglicans, Irish colonists mainly Catholics, and Scottish colonists Presbyterian. The Wesleyans sent a large number of ministers to the colonies from the 1820’s onward and gained many converts. Smaller religious groups included Baptists, Jews, and Quakers. Colonists were allowed to worship as they chose.

In the 1830’s, the governments of New South Wales and Van Diemen’s Land began to provide financial assistance to the four main denominational groups. Government aid subsidized the building of churches and the salaries of ministers.

Church attendance was low in the colonies. Many working-class colonists had little regard for organized religion and pious behavior. Many colonists disobeyed government orders requiring people to attend church and to observe the Sabbath by not working and not getting drunk. Sundays became a day for entertainment and idleness rather than a day for religious observance.

Education

Religion had a strong influence on education in the colonies. Richard Johnson, an English clergyman who served as the chaplain of New South Wales, also had the responsibility for overseeing education in the colony. His supervision established a pattern of church domination in education that remained throughout the first half of the 1800’s.

The Anglican Church largely controlled education in both Australia and New Zealand. Schools operated under the supervision of clergymen. Religious bodies in England supported the salaries of teachers and sent other aid, such as books. The government allocated land for schools, but it did not provide funding to build or staff them. The early schools focused on teaching their pupils to read and write to ensure that young people could read the Bible.

During the 1780’s, many British people began to establish Sunday schools for the poorer children who worked during the week. These schools quickly spread throughout the British colonies. Sunday schools emphasized reading, writing, and arithmetic, as well as Bible studies.

The children of the middle and upper classes received a better education. Some middle-class families sent their boys to private schools that taught a wide range of subjects, including science, commerce, Latin, Greek, and mathematics. Many middle-class mothers also gave their children lessons in the home. Likewise, the children of the upper class received much of their education at home, especially the sons and daughters of isolated landowners. A tutor or governess usually gave the lessons. Other upper-class families sent their sons to private boarding schools in Australia or in the United Kingdom. Education for upper-class girls was not considered important, though some girls’ schools did operate. However, these schools tended to concentrate on morals and etiquette rather than academic subjects.

By 1815, an assortment of public and private schools existed in the colonies. They had a number of different aims, used a variety of teaching methods, and offered a range of subjects. Schools tended to be small, and most teachers were men.

The first evening schools for adults were established in Australia in the early years of the 1800’s. These developed in the 1830’s into mechanics’ institutes, organizations formed to provide education, particularly in technical subjects, to working adults. Mechanics’ institutes were quickly established in all the colonies.

In 1850, Australia’s first university, the University of Sydney, was established. Three years later, the University of Melbourne was founded.

In New Zealand, as in Australia, churches played an important role in the establishment of education. As early as 1816, missionaries opened the first schools for the education of Māori. By the 1830’s, schools in Māori villages were flourishing. The mass European colonization of New Zealand began in the 1840’s, about 50 years later than in Australia. The colonists who established settlement towns such as Wellington and Nelson quickly set up schools for their children. Educational facilities for adults were established around the same time as those for children. In 1842, mechanics’ institutes were founded in Wellington, Auckland, and Nelson. The first New Zealand university, the University of Otago , was not founded until 1869.

Recreation

Government officials and wealthy landowners lived a privileged life in the colonies. They entertained one another at lavish dinner parties, balls, and picnics. Hunting and fishing were also popular pastimes.

Ordinary people relied on other types of recreation to brighten their lives. The first settlers brought a love of sports with them. Boxing, cricket, horse racing, and later football (soccer) were popular pastimes. Only men played most sports during this early colonial period. Women watched from the sidelines.

Horse racing was popular with all sectors of society. Initially, a lack of thoroughbreds meant that race meetings were open to all horses. Many hacks (horses used for riding or pulling a carriage) took part in races.

Cricket was the first organized team sport played regularly in Australia and New Zealand. It was a major spectator sport played widely throughout the colonies and appealed to all sections of colonial society.

Boxing also was a popular early spectator sport in Australia. However, the authorities discouraged prize fighting, and fights often took place away from the prying eyes of soldiers and police.

From the early 1800’s, rowing races were held on the harbors of both Sydney and Hobart. Initially, the crews of different ships competed against each other in informal events. By the end of the 1820’s, rowing had become a popular sport conducted on a regular basis. The first formal regatta (series of boat races) was held on Sydney Harbour in 1827. By the end of the 1830’s, regattas were part of many outdoor festivals.

In the early colonial period, tavernkeepers used to organize foot races, both walking and running, for the entertainment of their customers. Foot-racing—or pedestrianism, as it was then called—attracted large crowds. A well-known competitor in the 1840’s was William Francis King, a pie seller known as “the Flying Pieman.” He often engaged in long-distance races, sometimes carrying an animal across his shoulders.

Swimming was a popular early colonial activity. Within the first year of settlement, the marines of the First Fleet had constructed a swimming enclosure on Sydney Harbour. By the mid-1830’s, swimming was commonly recognized as Sydney’s favorite recreation, and a number of public swimming pools had opened.

Gambling was a favorite pastime with ordinary people. Card games were particularly popular, so much so that early convicts converted Bibles into cards for gambling. The colonists wagered on the outcome of many contests, including cockfighting, dogfighting, boxing, and wrestling.

Heavy drinking and drunkenness were common in the colonies. Drinking allowed colonists to forget, if only briefly, the harsh conditions of their lives. The temperance movement, a campaign to end the consumption of alcoholic beverages, arrived from the United Kingdom in the 1830’s. Most churches in Australia and New Zealand supported the movement.

Taverns, inns, or public houses—commonly called pubs—were favorite gathering places. They served as centers of popular entertainment as well as drinking. Many had areas for the playing of skittles, a game that resembles bowling, and quoits, a game that resembles horseshoe pitching. Other taverns offered singing rooms, musical and theatrical entertainment, card playing, casino games, backgammon, and billiards. Pubs were noisy places, filled with singing, dancing, and revelry. Usually only men frequented drinking establishments. Women might work in pubs as barmaids, but they generally did not drink in them.

Live theater, including comedy shows, drama, and musicals, was popular. Between 1800 and 1825, there were only isolated performances under special circumstances, requiring the permission of the governor. From the 1840’s onward, though, the number of theaters throughout the colonies grew. A number of theatrical companies toured and performed in provincial towns. Touring companies would engage local amateurs to supplement the small numbers of professional actors that made up the troupe.