Squatters in Australia were originally cattle and sheep ranchers who occupied land illegally. Later, many of them became wealthy and respected ranchers.

The squatters’ first dwellings were pioneer huts. As they became better off, they built brick houses and then larger houses of two stories with spacious entrances. Other buildings were constructed around the homesteads, and small villages developed.

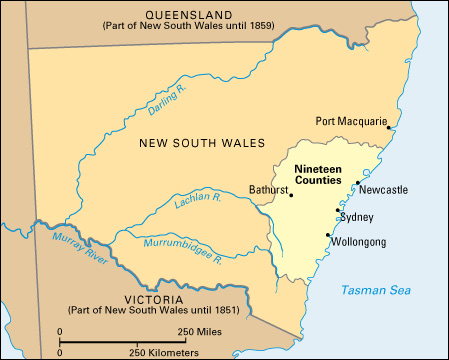

In 1821, nearly 40,000 people lived in eastern Australia. But the colonists were still confined to a few coastal settlements in New South Wales and Van Diemen’s Land (now Tasmania). From 1820 onward, colonial explorers and settlers began to push beyond the frontiers of British settlement in search of new farming and pasture lands. The government tried to limit settlement to the already settled districts of New South Wales called the Nineteen Counties. It decreed that all other settlement was illegal. But the need for more land and the growth of the wool industry prompted many settlers to travel outside the Nineteen Counties. Eventually, this natural growth forced the government to change its policy.

The first official use of the word squatter in Australia seems to have been made in Van Diemen’s Land. On June 3, 1828, Governor George Arthur issued an order stating that “the practice of squatting has been followed for the most part by freed convicts possessing sheep, probably acquired by the most exceptional means.” He implied that the sheep were stolen and said that, with these thefts, the freed convicts started their own sheep runs (stretches of land used to graze livestock). Wealthy, and usually socially important, landowners within the Nineteen Counties of New South Wales had also grabbed land beyond the legal bounds. These landowners called themselves gentlemen settlers. They regarded the ordinary people who moved into those distant areas as undesirables—men who, they said, stole sheep. They accused the newcomers of setting up grogshops (liquor shops), of selling liquor at exorbitant prices, and of causing drunkenness among workers employed on large stations. The big landholders called these intruders squatters.

In 1836, the government began allowing the squatters to buy licenses to pasture their stocks beyond the limits for 10 British pounds a year. After 1836, the word squatter referred to any landowner who paid 10 pounds a year to graze cattle and sheep in distant parts of the country.

By 1847, the squatters won the right to lease their runs for periods of 14 years. After the 14 years, they could purchase the land if they wished.

The squatters’ lives

The first squatters

were large landowners within the Nineteen Counties who realized that their overstocked land had become poor. They looked for better pastures in the forbidden territory. They kept riding until they found good grass and, if possible, permanent water. There they would squat. The practice cost little. Before 1836, they paid nothing for as much land as they wanted to occupy. After 1836, the land still cost only 10 pounds each year. These wealthy squatters normally brought out overseers, shepherds, and assigned convicts (convicts who labored for free settlers in return for food, clothing, and shelter).

Newcomers

who arrived from Britain (now the United Kingdom) generally had little capital. Lured to Australia by tales of almost instant wealth from wool, many decided to start stations (ranches) beyond the Nineteen Counties. As they moved through the interior, they were often roughly pushed farther out by overseers on the big stations. If they found suitable country, they then had to return to Sydney to try to obtain a loan from a bank or merchant trader. If they got a loan, they had to pay a high rate of interest. They used the money to buy necessary equipment and, if their funds lasted, they hired one or two helpers. Because they did not have land within the Nineteen Counties, they could not hire convicts. On the way to the bush, as Australians call the remote countryside, they generally bought stock from the overseers.

New squatters who endured the sapping heat of an Australian summer and survived problems with the Aboriginal inhabitants of the land sometimes succeeded. They also had to learn quickly, particularly about dealing with diseases in sheep, such as footrot, scab, and catarrh. Many failed and returned to the city.

Women’s lives.

The hard physical work on stations was considered too difficult for most women. Most of the squatters did not want women about the place. Some of the small squatters left their wives in the city.

Women who did go into the outback, as Australians call the interior of the continent, had to endure many hardships and worries. They often had to do what was considered men’s work. In cases of family sickness or childbirth, they might not find a doctor within 100 or more miles or kilometers. Seldom did they see another woman.

Work

—hard work—had to be done during every day and night in the year. Laborers had to shepherd the sheep during the day and watch them at night. They had to assist at lambing. At shearing time, they washed the sheep, pressed the wool into bales, and loaded the bales onto the wagons. Some laborers took bullock wagons over hundreds of miles or kilometers of rough tracks to the city or drove cattle to the saleyards.

The squatters found it difficult to keep free men on the distant stations. The workers tired of the endless labor and the monotony and dreariness of their lives. The far outback offered virtually nothing in the way of pleasure or recreation. In 1837, there was a shortage of 3,000 shepherds in the colony.

The squatting age

The remarkable increases in livestock—both cattle and sheep—from the beginning of the colony in 1788 to the present time is one of the great stories of Australia’s development. Today, Australia’s ranchers own about 31 million cattle and about 140 million sheep. If the government had prevented squatting—originally the illegal possession of land in the outback—those numbers would have been much smaller.

The first animals

were obtained by Governor Arthur Phillip at the Cape of Good Hope, now in South Africa, during the First Fleet‘s voyage from Britain to Australia. Phillip bought 1 stallion, 3 mares, 3 colts, 6 cows, 2 bulls, 44 sheep, 28 pigs, and 4 goats.

Phillip started farms, first on the site of the present Royal Botanic Gardens, in Sydney, and, later, on more suitable ground at Parramatta. He was able to get more livestock in 1791 and 1792.

Phillip left for England in December 1792. Major Francis Grose of the New South Wales Corps served as temporary governor until December 1794. Two important events occurred during Grose’s time—the first free settlers arrived, and the officers and officials were given grants of land. Soon the officers sent to the Cape of Good Hope and Calcutta (now Kolkata), India, for more livestock.

John Macarthur,

a lieutenant in the New South Wales Corps, was the most industrious of the officers. In 1797, two of his friends returned from the Cape with several pureblood Spanish Merino sheep. Macarthur bought three rams and five ewes from them. He adopted a practice of first crossing the Merinos with local breeds and then mating the female offspring with Merino rams for four generations. The resulting sheep had fine wool, to Macarthur’s delight. He continued his experiments, and eventually his wool was equal in quality to the fine wools from Spain and Germany. For many years, these two countries had supplied most of the wool used in the woolen mills of England. Macarthur’s pioneering efforts in fine-wool production brought great wealth to Australia.

By 1800, the colony had overcome many of its early difficulties. It now had 6,124 sheep—5,499 owned privately by officials, officers, and settlers—and 1,044 cattle, three out of four of them on government farms.

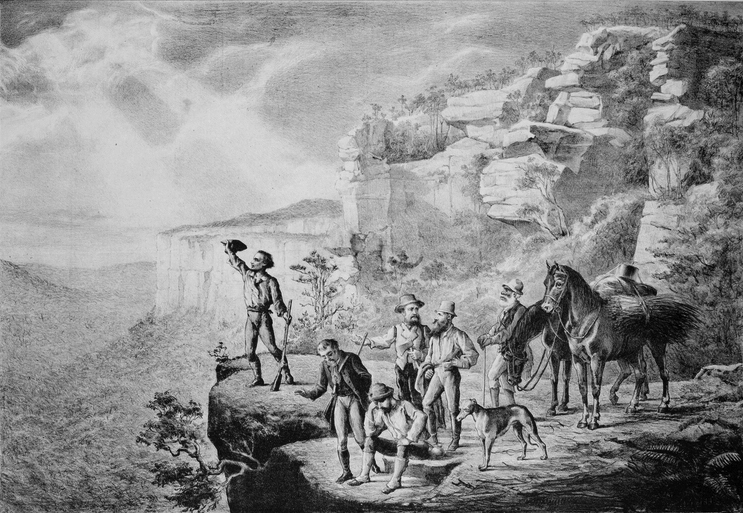

Exploration.

From 1810 to 1812, caterpillar plagues and dry weather troubled the colony. One wealthy landowner, Gregory Blaxland, feared that he would lose many of his stock if he did not find better pastures. He hoped that he might find good grassland over the Blue Mountains, which had not been crossed. In 1813, Blaxland, with the Australian rancher William Lawson and the Australian explorer and statesman William Charles Wentworth, followed the main ridge across the mountains. In the following year, the English explorer George William Evans continued past their terminal point, Mount Blaxland. Evans made his way to a place about 40 miles (64 kilometers) beyond present-day Bathurst. Joyfully, he wrote that he had traveled through “finer country than I can describe—the increase of stock for some 100 years cannot overrun it.” The explorers were rewarded with grants of land.

Lachlan Macquarie,

who was governor from 1810 to 1821, did not want private sheep and cattle ranchers to cross the Blue Mountains. He regarded the mountains as prison walls that served to keep the convicts within the narrow bounds of settlement.

Commissioner John Thomas Bigge, sent to investigate Macquarie‘s administration, told Macquarie that he thought private settlers should be allowed to occupy land in the new country. Reluctantly, Macquarie issued an order on Nov. 25, 1820, giving people limited use of the interior. That order was the real beginning of the rapid spread into the vast outback.

To the government of the United Kingdom, Bigge recommended that large grants of land be given in the new areas to people who had sufficient money to start big stations. He pointed out that the governor would be spared the expense of feeding and clothing any convicts sent to work on the stations. Bigge also recommended that the colony should be surveyed so that settlers could know the exact boundaries of their properties.

Free settlers.

In a book printed in the United Kingdom in 1819, William Charles Wentworth wrote enthusiastically about the opportunities the colony offered to those who were prepared to invest money in sheep and cattle stations. That praise of New South Wales, and the British government’s decision to adopt Bigge’s recommendation for liberal grants of land, encouraged many to emigrate to Australia.

Sir Thomas Brisbane, governor from December 1821 to December 1825, gave large grants to settlers of capital. His successor, Ralph Darling, wrote that during those years “1,068,000 acres were granted, and, in many cases, settlers were in occupation over an extensive area without survey.” The lack of surveying caused a chaotic state of affairs. Many settlers did not know where their grants started and finished. At times, serious conflicts resulted from disputes over boundaries.

Most grants ranged between 633 and 2,530 acres (256 and 1,024 hectares), according to the wealth or importance of the applicant. The largest ever made went to the Australian Agricultural Company. In 1824, a group of people met in London to form this company with a capital of 1 million pounds made up of shares of 100 pounds each. Its shareholders included influential and rich men. Twenty-seven were British parliamentarians, and others were wealthy landowners in New South Wales. Within five months, the company received a charter. Later, it asked the governor, Sir Richard Bourke, to grant it two huge areas in the colony—areas later known as Warrah, near Quirindi, and Goonoo Goonoo, near Tamworth. This request upset many of the nearby small squatters, who would be cut off from running water to their properties.

During the 1820’s, English woolen manufacturers continued to buy most of their fine wool from Spain and Germany. Australian ranchers knew that only by improving the quality of their fine wool could they hope to sell more fleece to England. To accomplish this, the ranchers obtained more pure Merinos and crossbred their flocks.

The Nineteen Counties.

Ralph Darling, who was governor from 1825 to 1831, followed instructions and began dividing the colony into counties, hundreds, and parishes. The limits of location were decided upon in 1826. These limits were more definitely located in 1829. The Nineteen Counties established at this time covered 33,306 square miles (86,262 square kilometers). They extended from the Manning River in the north, to Wellington in the west, to Yass in the southwest, and to the outlet of the Moruya River in the south.

The authorities permitted settlers to select land within these limits. The wide land beyond was forbidden territory—”the land beyond authorized occupation.” However, despite the regulations, many people occupied illegally the land outside the limits.

By 1834, the Scottish surveyor Thomas Mitchell and his assistants completed 900 accurate maps of the territory within the Nineteen Counties. He also produced a Map of the Nineteen Counties. Mitchell’s work made it possible for each landowner within the Nineteen Counties to obtain an accurate description of the limits of his property.

In 1831, the secretary of state, Viscount Goderich, made an important change in land matters. No more free grants were to be made in the Nineteen Counties. The government was to start selling land at a minimum price per acre. Goderich proposed that the money taken in be spent to pay the passage of new colonists, mainly unemployed English laborers.

Existing landowners, who took up land adjoining or near their holdings, made most of the purchases. Most new settlers had limited capital and could not afford to purchase land, equipment, and stock. New settlers usually went out into the forbidden territory, where they could occupy as much land as they wished without payment. These new settlers often had to travel far into the interior to find land, because the great landholders in the Nineteen Counties already occupied vast areas beyond “the limits of authorized settlement.”

Growth of the wool industry.

The sheep industry enjoyed a boom period during the 1830’s. Ranchers enjoyed a succession of favorable seasons. They also received high prices for their export wool. By 1836, colonists in the forbidden territory were producing more wool and getting a greater financial return than those in the Nineteen Counties.

Sir Richard Bourke, who was governor from 1831 to 1837, stated in 1834, “It is not the policy, nor would it be within the power of government, to prevent an occupation which produces so profitable a return.”

The Act of 1836.

Bourke decided that, before he left New South Wales, he would establish the right of the Crown over the land beyond the Nineteen Counties. He passed an act allowing anybody to occupy land in those outback areas after the payment of an annual fee of 10 pounds. A settler who paid the 10 pounds could occupy any area of land. The fee remained the same whether one acre or tens of thousands of acres were used. Many said that the act favored the wealthy settlers with huge flocks. Bourke appointed seven commissioners, one to each of seven roughly described districts, to collect the fees and settle quarrels. The main result of the Act of 1836 was that from that time there was no longer any illegal territory.

The Act of 1839.

Sir George Gipps was governor of New South Wales from 1838 to 1846. Soon after his arrival, Gipps heard tales of the murders of settlers and the dispersal of their stock by Aboriginal people. He was told of the slaughter of Aboriginal people by organized bands of squatters. These tales convinced him that the 1836 Act was wrong in not providing for police protection in the outback. To correct this situation, Gipps passed an act in 1839 requiring each squatter to pay an annual license fee of 10 pounds plus annual livestock fees for each sheep, head of cattle, and horse owned. Gipps appointed nine commissioners in various districts and assigned border police to work with them. The stock fees were to be used to maintain the border police. In the Act of 1839, the government took the first step toward making the outback a safer place.

At the end of 1839, the extent of squatter country ranged from the present northern border of New South Wales to its southern border, as far west as Bourke, and included much of present Victoria. Until 1851, the state of Victoria was a part of New South Wales.

The spread of cattle and sheep ranching

Van Diemen’s Land

(now Tasmania) did not have squatters to the same extent as the mainland. It had its cattle and sheep, but the considerable area of mountainous country on the small island prevented large-scale expansion of ranchland. The pioneering Henty family might well have played an important role in the wool and cattle industries there, but Thomas Henty’s children left the settlement of Launceston in the 1830’s.

Victoria.

Two of Thomas Henty’s sons, Edward and Frank, landed at Portland Bay at the end of 1834, bringing cattle and fine-wool sheep provided by their father in Launceston. Their fine-wool sheep were the first Merino sheep in Victoria. Soon, James, Stephen, Charles, and John Henty followed their brothers.

In August 1836, Sir Thomas Mitchell explored the area of western Victoria, which he called Australia Felix. When he arrived at Portland Bay, he saw Edward and Frank Henty, who were then well-established as settlers and were also engaged in whaling. When Mitchell returned to Sydney, he wrote of the lands he had seen in western and central Victoria as “another Eden.” Within months, a procession of colonists began arriving from the north.

By the end of 1845, the southern district, which is now Victoria, had 231,602 cattle and 1,792,527 sheep. Of these, squatters pastured 200,973 cattle and 1,430,914 sheep beyond the authorized bounds. Victoria had become the land of the squatters.

In 1836, the era of the stock overlanders (drovers) began. These hardy and fearless people drove cattle and sheep over hundreds of miles or kilometers by contract, or for sale to distant squatters. There were no roads for them to follow.

South Australia.

The dry north and west of South Australia provided few opportunities for squatters. However, in the southwest, with Rivoli Bay as the assembly area, there was much activity in the 1840’s.

Western Australia

had its beginnings at King George’s Sound in 1826 and Perth in 1829. Its isolation, the unsuitability of the land for extensive grazing, and the difficulty of obtaining large numbers of cattle and sheep were the main reasons why few squatters tried to settle there.

Queensland.

In 1827, the English botanist and explorer Allan Cunningham discovered “extensive tracts of clear country” in the Darling Downs, in present southern Queensland. Queensland was a part of New South Wales until 1859.

In 1840, the Scottish-born settler Patrick Leslie, finding most of the New England district had been occupied, decided to move to the Downs. There Leslie established the first of the great Downs stations, which he named Canning Downs. By 1849, there were 60 runs in the Downs.

When, in 1842, there were 45 stations in the Moreton Bay district, the government decided to form a district for it as well as one for the Darling Downs, each with a commissioner to collect the fees.

Occupation and purchase regulations.

Governor Gipps published Occupation Regulations on April 2, 1844. An annual fee of 10 pounds was to be paid for each station of 20 square miles (50 square kilometers). The commissioner could vary this area because in dry areas a larger area was needed to graze 4,000 sheep or 500 head of cattle. Some big squatters, such as Benjamin Boyd, had vast holdings carrying 200,000 sheep. These ranchers protested that the fees were exorbitant. They complained that they had neither security of tenure nor the first right of purchase.

Gipps, in his Purchase Regulations of May 13, 1844, made some concessions to the squatters. A squatter after five years’ occupancy could buy 320 acres (128 hectares) at 1 pound per acre as a homestead site, and each eight years thereafter, an additional 320 acres at 1 pound per acre. In this way, each successive purchase of 320 acres acted as a renewal of an eight years’ lease.

The big squatters were still angry. They wanted longer leases and the first right of purchase. The United Kingdom approved the Occupation Regulations but postponed a decision on the Purchase Regulations. The manufacturers of woolen products continued to ask for special treatment for the squatters. They wanted 21-year leases and provided powerful arguments in their favor. From 1842 to 1845, they said, the export of wool from Australia rose from about 9 million to 18 million pounds (4 million to 8 million kilograms). There was no need for them to point out that most of this wool came from squatters in the outback. The report of 1845 showed that there were 448,270 cattle and 2,252,712 sheep within the boundaries. Outside the boundaries, there were 899,752 cattle and 3,949,319 sheep. The secretary of state decided to give special concessions to the squatters. By Order-in-Council, March 9, 1847, the British government gave 14-year leases to squatters in “the unsettled areas.” During that time, the lessee alone could purchase either the whole station or a minimum of 160 acres (64 hectares), at 1 pound per acre, at any time the lessee wished. At the end of the lease time, the squatter had the right of renewal. The annual license fee was set at 10 pounds for the pasturing of 4,000 sheep or 500 head of cattle.

Such favorable treatment far exceeded anything the big squatters could have expected. They were guaranteed security of tenure and the right to purchase, and would be paying very low fees for their leases. As a result of this legislation, large squatters held much of the vast interior legally for many years afterward.