Scotland, History of. The history of Scotland is the story of the people who settled on the northern part of the island of Great Britain. In the earliest times in Scotland’s history, five different peoples lived in the area: Angles, Britons, Gaels, Picts, and Vikings. Invading powers, such as the Romans, shaped the history and culture of Scotland. Until the 1700’s, Scotland and England were separate countries that often came into conflict. In 1603, Scotland’s king, James VI, came to the English throne as James I. Through the Act of Union of 1707, England and Wales joined with Scotland to form the Kingdom of Great Britain. This union expanded further in 1801, when Ireland was joined with Great Britain to form the United Kingdom.

In the 1900’s, the divisions of the United Kingdom sought self-government. The southern counties of Ireland gained independence. Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland gained some self-government in a transfer of power called devolution. From this history of union and devolution, Scotland has developed a rich heritage.

Prehistoric Scotland

Archaeologists think that the earliest hominins (the group including modern humans, their close relatives, and their ancestors) may have entered Britain overland from Europe more than half a million years ago. These hominins belonged to the Paleolithic Period (Old Stone Age), which began over 2 million years ago and lasted until about 8000 B.C. Historians believe that the first people to live in Scotland came from what is now England about 7,000 to 7,500 B.C. These earliest inhabitants probably survived by gathering edible plants, hunting, and fishing. They probably moved around in search of food sources. Morton, in Fife, has the remains of a settlement from that time.

About 6,000 years ago, or about 4000 B.C., knowledge of agriculture was brought from the mainland of western Europe to Britain. During this period, settlers arrived in larger numbers. Archaeologists have discovered chambered stone mounds, called cairns, in which the people buried their dead. Pottery, bones, and grain found with these burials indicate that the people were farmers who had some social organization. In the late 1970’s, archaeologists found in eastern Scotland a huge timber hall that they believe dates from this period.

The Bronze Age.

Between 3000 B.C. and 2500 B.C., people began using metal in Britain. Knowledge of metalworking spread from Iberia (modern Spain and Portugal) to Ireland and then to Britain and north to Scotland. It also came from the Rhineland, an area around the Rhine River in what is now western Germany, and from what is now the Netherlands. The first metals used were copper and gold. At nearly the same time, distinctive beaker-shaped pottery vessels appeared in Scotland. The beakers were often buried with the dead.

Scholars once thought that large numbers of immigrants, whom they called the Beaker Folk, brought metalworking and the new beaker pottery to Britain. But archaeologists have not found evidence of large migrations, and many now believe that small groups or individual traders and craftworkers probably spread the new skills and ideas.

After 2000 B.C., people began making objects of bronze (copper hardened with tin). Collections of weapons that survive from the period after 1000 B.C. indicate that warriors ruled the Bronze Age society of Scotland. After about 700 B.C., people started using iron rather than bronze. Because iron rusts away, few objects from this period have survived. But archaeologists have identified many settlements from this period, notably forts.

The inhabitants of Scotland began about 600 B.C. to build hill forts with ramparts (wide banks of earth built around the fort to help defend it). Later, they built tower structures called brochs. People may have used these structures as both farmhouses and places of safety. Brochs date from about 500 B.C. to A.D. 200. The best-preserved broch is in Mousa in Shetland.

Roman Scotland

Picts, Scots, Angles, and Britons.

In A.D. 43, the Roman emperor Claudius ordered Roman armies to invade Britain. They conquered the British tribes as far north as Yorkshire by about 78. The Romans found British tribes south of the rivers Clyde and Forth. These tribespeople spoke a Celtic language related to Welsh and Cornish.

In A.D. 80, the Roman general Gnaeus Julius Agricola led his force into Scotland past the River Forth. The Romans called the people there Picts (painted people) because they painted their bodies. The Picts’ language resembled the Celtic language spoken by the Britons to the south, but it also preserved elements of an earlier language not related to other European languages.

The Romans won a great victory over the Picts at Mons Graupius in A.D. 84, somewhere in northeastern Scotland. The Roman historian Cornelius Tacitus described the battle, but modern historians disagree over its exact location. Also in 84, the Roman emperor Domitian ordered Agricola to return to Rome, and the Romans withdrew southward from Scotland.

As part of a defensive strategy, the Romans in A.D. 121 built Hadrian’s Wall, which stretched between the River Tyne and the Solway Firth. It was named after the Roman emperor Hadrian. Around 141, the Romans added the Antonine Wall, a turf structure between the River Forth and the River Clyde. Under attack from local tribes, the Romans soon abandoned that area and withdrew farther south. Hadrian’s Wall became their northern frontier. The Romans withdrew from all of Britain in the 400’s.

About A.D. 500, a Celtic tribe called the Scots came from northern Ireland and settled on Scotland’s west coast. They spoke Gaelic.

Christianity

was practiced by the Romans who occupied Scotland in the early A.D. 100’s and 200’s. Around A.D. 500, Saint Ninian, a British bishop, came to Whithorn in what is now Dumfries and Galloway in southern Scotland. There he built a church and possibly a school. He sent missionaries out among the Picts. Saint Columba (also known as Colmcille) sailed to Iona from Ireland in 563 and spread Christianity among the Picts. Pictland was mostly Christian by A.D. 700.

After the late 600’s, the Picts came to rule large parts of Scotland. The most powerful kings ruled at Fortriu, in the area of Scone. In 685, the Picts decisively defeated Angle invaders at the Battle of Nechtansmere, in what is now Angus. The Angles were one of the Germanic peoples who invaded Britain during the A.D. 400’s and 500’s. The Battle of Nechtansmere helped stop the northern spread of Anglian influence.

The Pictish monarchy absorbed many external influences, especially from the Scots of the west. The Picts often dominated the Scots in the 700’s and early 800’s. But a series of Viking raids in the 800’s might have weakened Pictland. About 843, a Scottish king, Kenneth I MacAlpin, took over the Pictish monarchy and began ruling both peoples from Pictland. He established Alba, the first united kingdom in Scotland. The Picts ceased to exist as a separate people about A.D. 900.

After the MacAlpin dynasty came to power, the Gaelic language spread to the whole of mainland Scotland north of the River Forth. The Pictish language disappeared.

The kingdom of Scotland

In the late 800’s, the Vikings overran the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Northumbria, the most northerly of the early English kingdoms. By about 1018, the Scottish King Malcolm II had gained control of Lothian, the northern part of Northumbria. At the same time, he also gained Strathclyde, a British kingdom along the western coast that included Dumbarton and areas south of the River Clyde. Orkney and Shetland remained under the control of the Vikings, and the Scottish kings formally abandoned the Western Isles to Norway in 1098.

Violent struggles for the Scottish throne

began in the late 900’s. In 997, Kenneth III became king by killing Constantine III. In 1005, Malcolm II killed Kenneth III. Duncan I, who followed Malcolm II, was killed in battle fighting Macbeth, the ruler of Moray in northern Scotland, in 1040. In 1057, Duncan’s son, Malcolm III Canmore, killed Macbeth. The following year, he killed Macbeth’s stepson Lulach. Malcolm III became king in 1058 and reigned for 35 years.

From the late 1000’s onward, Scotland gradually lost its mainly Celtic character. It took on a mixture of Celtic and Anglian characteristics. Malcolm III founded a dynasty (royal line) whose members were particularly open to influences from England. Malcolm III married Margaret, the granddaughter of King Edmund II of England, and was greatly influenced by English customs. After the Normans conquered England in 1066, Malcolm permitted English people who opposed the new Norman king of England, William the Conqueror, to settle in Scotland. Margaret helped introduce reforms in the Scottish church that were similar to reforms carried out in Europe. See Margaret of Scotland, Saint.

Malcolm III’s son David I, who ruled from 1124 to 1153, continued Malcolm’s policy of allowing English settlers into Scotland. These settlers were nobles to whom David granted large pieces of land. They became powerful local lords and supplied knights to the king.

During this period, Scotland developed a new system of administration with locally based justices and sheriffs. David I created such new offices as chancellor, chamberlain, and steward to supervise the administration of the kingdom. He also chartered towns called burghs, which had markets and generated revenue for the state. David introduced the minting of coins in Scotland, which aided trade. He founded some abbeys and donated generously to others. The abbeys produced goods and services that benefited the economy.

Struggles with England.

The English wanted to control the entire island of Great Britain, including Scotland. But the Scots were determined to remain independent. They frequently sided with France against the English when England and France came into conflict.

David I and his heirs also sought territory in England. David took advantage of a civil war in England to extend the Scottish border south to the River Tees. His marriage to Matilda (also known as Maud), daughter of the Earl of Huntingdon, gave him a claim to the earldom of Northumbria. David obtained the earldom for his son Henry, who ruled it from 1138 until 1152. But Henry’s son Malcolm IV lost the earldom in 1157. Malcolm’s brother William (later known as William the Lion) came to the throne in 1165 and tried to regain Northumbria. In 1173, Henry II of England was dealing with a rebellion. William marched on England but was defeated and captured at Alnwick in 1174. After William’s defeat, Scotland became a vassal (dependent) kingdom of England until 1189. William’s son Alexander II became involved in a rebellion in England from 1215 to 1217. In 1237, he gave up all claims to Northumbria.

Alexander II, after his unsuccessful conflict with England, made peace with King Henry III. Alexander married Henry’s sister Joan in 1221. From 1217 to 1296, Scotland and England were at peace. During that time, the Scottish kingdom enjoyed economic stability and good government. Agriculture and trade flourished, and many roads and bridges were built. The Scots, especially the wealthy ones, began to develop a sense of community and even nationality. Scotland, although tied economically to England, began to think of itself as an independent state.

In 1263, the Scots fought off a Norwegian attack. As a result of the peace terms between Scotland and Norway, the Western Isles were restored to Scotland in 1266.

At the death of Alexander III in 1286, there were no more direct male heirs from the House of Malcolm Canmore. Alexander’s only descendant was a 3-year-old child, his granddaughter Margaret, called the Maid of Norway. She took the throne, but six guardians, appointed by a group of Scots called the Community of the Realm, governed Scotland. They arranged a marriage between Margaret and the son of Edward I of England.

Margaret died under mysterious circumstances in 1290. Her death led to a crisis over succession to the throne. Thirteen contenders claimed a right to the throne. The Scots were so divided over the decision of who should become king that they turned to King Edward for a decision. Edward demanded that each of the contenders acknowledge him as overlord. In 1292, Edward’s court chose John Balliol, a descendant of David I, as heir to the Scottish throne.

Edward insisted on his feudal rights in Scotland and limited Balliol’s authority by overriding decisions made by Balliol’s own court. In 1294, Edward went to war with France. He demanded the support of his lords and knights, including Balliol. Balliol refused to help Edward and instead made a treaty with France. Edward sent his troops to Scotland and defeated the Scots at Dunbar in 1296. Balliol resigned, and Edward occupied Scotland, appointing his own administration there. Edward also removed the Stone of Scone, the Scottish symbol of royal authority. Edward had the Coronation Chair in Westminster Abbey built to hold the stone.

In 1297, the angry Scots rebelled against Edward’s authority. William Wallace, Scotland’s first popular hero, decisively defeated the English at Stirling. Edward, in turn, won a great victory at Falkirk in 1298, but did not reoccupy Scotland until 1304. In 1305, the English captured and executed Wallace.

Edward II, who became king of England in 1307, had to face a new rebellion in Scotland. In 1306, Robert Bruce, whose grandfather had been Balliol’s rival to become king in 1290, seized the throne. Bruce began his bid to free the Scottish kingdom from English control and had himself crowned Robert I, king of Scotland. He then took advantage of the great resentment the English occupation caused among the Scottish people.

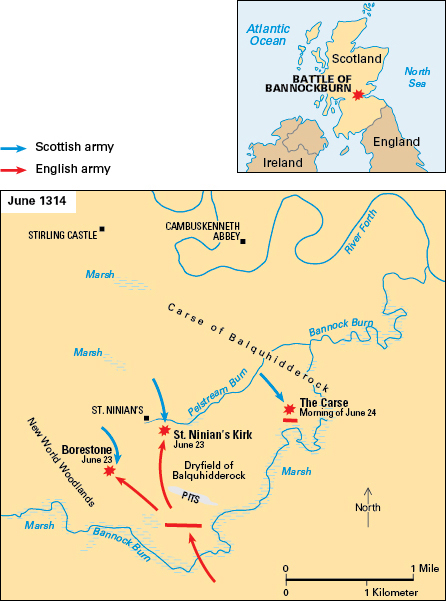

On June 24, 1314, at the Battle of Bannockburn, Robert’s forces defeated a far superior English army. With the fall of Berwick to Scottish forces in 1318, all of Scotland became free. The Scots officially declared their independence in 1320. English and Scottish troops continued to raid each other’s borders until Edward II and Robert agreed to a truce in 1323. In 1327, Robert vowed to renew hostilities unless England acknowledged Scotland’s independence. In 1328, Edward III finally recognized Robert as King Robert I of Scotland. Robert died in 1329. His 5-year-old son succeeded him as David II.

Beginning in 1332, Edward III offered political and military backing to the Balliol family against David. As a result of English support, Edward Balliol, John Balliol’s son, was crowned king in September 1332. David’s supporters sent the boy to France for safety two years later. David returned to Scotland in 1341. He soon began making raids into northern England. He was defeated five years after his return at Neville’s Cross, near Durham.

The English held David II prisoner from 1346 to 1357. In David’s absence, his nephew, Robert the Steward, operated the government. To gain David’s release, Scotland was forced to pay England an enormous ransom in yearly installments for 10 years. David tried to arrange for the king of England or one of the king’s sons to succeed him if he had no male heir. But the Scottish Parliament twice rejected such a plan.

During the mid-1300’s, the Scottish population was devastated by the Black Death, an outbreak of plague that spread from central Asia across Europe. Many thousands of Scotland’s people were killed in the first outbreak, lasting from 1349 to 1350, and in a second outbreak from 1361 to 1362.

David II died childless in 1371. Robert the Steward was David’s closest heir. He took the throne as Robert II.

Independent Scotland

The first Stuarts.

Robert II was 55 when he came to the throne. He was descended from Walter Fitzalan, high steward of Scotland, and the position of steward had been passed down through the family. The position of steward gave the family its name, Stewart (also spelled Stuart, especially from the 1600’s onward). The Stuarts kept close ties with France and fought continually with England. Robert II’s son John, who ruled as Robert III, came to the throne in 1390 at about age 53. James I, only 11 years old, succeeded Robert III in 1406. English forces had kidnapped James a few weeks before his succession to the throne and did not release him until 1424. His uncle Robert, Duke of Albany, governed as regent (temporary ruler), until 1420, when Robert died. Robert’s son Murdoch then became Duke of Albany and regent. Neither regent tried to rescue James. After James’s return in 1424, James executed Murdoch. James victimized other noble families and imposed unpopular taxes, but he strengthened laws and the justice system. James was murdered at Perth in 1437.

James’s son, James II, was 6 years old when he succeeded his father in 1437. Nobles fought for power during his childhood. But when James came of age, he quickly took control. One family, the Earls of Douglas, became especially powerful under James II. In 1452, James uncovered what he believed was a conspiracy involving the Douglases. The king took part in the murder of the eighth earl, which provoked the Douglas family into revolt. James crushed the rebels and seized their estates.

In 1455, a struggle for the throne of England broke out between the House of Lancaster and the House of York. These wars were called the Wars of the Roses (1455-1485). During these wars, James set out to win back control of Berwick-upon-Tweed and Roxburgh Castle. In 1460, James was killed at the siege of Roxburgh Castle when one of his own cannons exploded.

James’s successor, James III, took the throne when he was 8 years old. James III’s childhood was peaceful. In 1461, Berwick was restored to Scottish rule. James’s mother and his cousin, Bishop James Kennedy, began to govern Scotland in James’s name. By 1465, they had both died. The Boyd family, a wealthy family of landowners, seized James III and proclaimed themselves his guardian, running the government. In 1469, James married Margaret, a daughter of Christian I of Denmark and Norway. That year, he took power back from the Boyds and ruled as king.

Through his marriage, James acquired the Orkney and Shetland islands for Scotland. James quarreled with his brothers Alexander, Duke of Albany, and John, Earl of Mar. John died mysteriously. Alexander fled to England and returned with an English army, which recaptured Berwick. James had long been unpopular with his nobles, and a group of them joined with the king’s own son James (later James IV) in rebellion. After a battle near Stirling in 1488, James was murdered.

Political and social developments.

The most important constitutional development of the early Stuart period was the evolution of a Scottish Parliament. Before the late 1200’s, kings consulted a king’s council, made up of clergy and nobles, on affairs of state. These councils laid the foundation for the holding of parliaments, and the name Parliament was first used in the 1290’s. In the early 1300’s, Scottish kings began summoning representatives from the burghs to grant taxes. Parliament came to have three estates (divisions)—clergy, nobles, and burgesses (town representatives).

Major developments also occurred in Scotland’s literature during the period from 1300 to 1513. The poet and historian John Barbour and the poet Blind Harry wrote important epic poems telling the stories of Robert Bruce and William Wallace. The poet Robert Henryson wrote a collection of fables, “Moral Fables,” as well as some longer poems. The poet William Dunbar wrote in a broad variety of styles, including hymns, satires, humorous verses, elegies, and allegories.

The Renaissance kings

James IV became king in 1488 at the age of 15. He proved himself to be a shrewd and strong king. In 1502, he signed a peace treaty with Henry VII of England and, in 1503, he married Princess Margaret Tudor, daughter of King Henry VII. Although James’s relations with England at this time were peaceful, the Scottish clans continued to be a problem.

By the early 1500’s, much of Scotland spoke the Scots language, which is closely related to English. Gaelic-speaking people lived in the mountains and along the western coast and followed their own customs. James IV took for himself the Lordship of the Isles, a traditional leadership role that had preserved order in the Highlands. In the 1500’s, the Scottish monarchs came to rely upon the Gordon family, who included the Earls of Huntly, to control the Highland clans, and the Campbell family, including the Earls of Argyll, to control the west. These two families, especially the Campbells, used their position to build up their own possessions. They deprived other families of land and property, creating discontent among the clans.

James IV and his successor, James V, who ruled from 1513 to 1542, lived well and spent much money. James IV spent large sums on ships and artillery. Both rulers also built or added onto costly palaces and castles, such as Falkland Palace, begun by James IV and completed by James V. To raise funds, James IV leased lands belonging to the monarch. Both James IV and James V squeezed money from church sources.

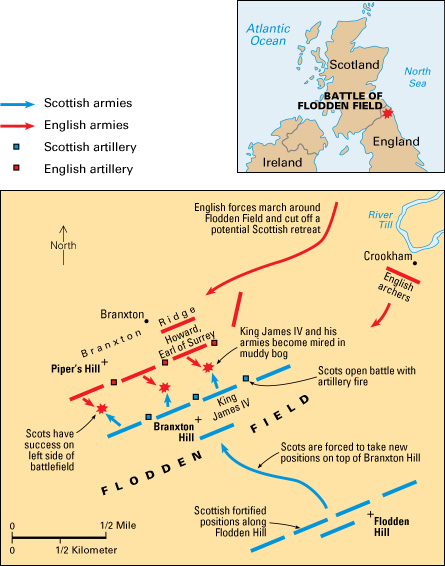

Both James IV and James V launched foolish wars against England. James IV had alliances with both France and England. In 1511, these two countries came into conflict, and James IV chose to side with France. In the brief war that followed, James IV led a Scottish invasion force that may have numbered over 30,000 men into England in August 1513. He faced English forces under the Earl of Surrey at the Battle of Flodden Field, just south of the River Tweed near Coldstream, on September 9. The Scots suffered a disastrous defeat at the hands of the English. James was killed, along with many of the Scottish nobility.

James V’s war was equally disastrous. He came to the throne as a child, and French and English interests fought for power in Scotland until he came of age. A branch of the Douglas family, the Earls of Angus, came to represent the English interest. They held James prisoner during part of his early life, but he drove them out in 1528. He tended to favor France and, in 1538, married Mary of Guise, daughter of a French duke. This marriage worried King Henry VIII of England, who sought to meet with James at York. James’s failure to meet with Henry eventually led to war. English troops invaded Scotland but were forced back. Scottish troops marched against England and were disastrously defeated at Solway Moss in 1542. James died soon afterward, leaving the throne to his baby daughter, Mary, Queen of Scots.

The Reformation

In the 1500’s, a religious movement called the Reformation led to the birth of Protestantism. The Reformation began when a German monk, Martin Luther, protested against certain practices of the Roman Catholic Church. Protestant influences reached England and increased religious discontent there. This development worried Scotland’s Catholic clergy. They paid heavy taxes to James V in the hope that he would not turn Protestant.

The Church faced numerous problems. Some bishops, including those chosen by the monarchs for personal or political reasons, were unsuitable for their work. Poor and ill-educated parish priests, following orders, handed over parish earnings to the monasteries, cathedrals, and universities, leaving too little for themselves. In addition, some higher members of the clergy lived extravagant and scandalous lives. The Church badly needed reform, but too many people profited from its disorganization to permit such changes.

The Scots tolerated a few church reformers, although some were burned as heretics (persons who opposed church teachings). John Knox, a follower of the Swiss religious leader John Calvin, at first found little support for his suggestions of sweeping changes. Then, as the religious issue became a political one, Knox received more support. Many Scottish nobles, anxious to remove the French influence promoted by Mary Guise, supported the religious reformers. Their actions led to a civil war from 1559 to 1560 that ended shortly after Mary of Guise died in June 1560. Under the Treaty of Edinburgh, French troops left Scotland. In August, the Scottish Parliament outlawed the Roman Catholic Mass, denied the authority of the pope, and adopted the Protestant Confession of Faith. The process of conversion was slow and the change was not widespread until about the end of the 1600’s.

Mary, Queen of Scots, daughter of James V and Mary of Guise, married the French dauphin (oldest son of the king of France), Francis, in 1558, briefly becoming queen of France in 1559. The civil war of 1559 to 1560 left her as Scotland’s queen. She was 18 years old, living outside of Scotland, and a Roman Catholic.

The union of the crowns

Mary, Queen of Scots, was a great-granddaughter of Henry VII of England. In 1558, Mary had offended Queen Elizabeth I by challenging Elizabeth’s right to the English throne. But in 1561, when Mary returned to Scotland from France, Elizabeth received her with tolerance. Mary practiced her Roman Catholic faith in private but followed the advice of her half-brother, the Earl of Moray, and did not oppose the spread of Protestantism. Later, Mary married Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley.

Soon Darnley became jealous of David Riccio (also spelled Rizzio), an Italian musician and possibly an agent of the pope. Riccio had come to Scotland in 1561 and won his way to the position of Mary’s secretary. Darnley joined a conspiracy and murdered Riccio. After the birth of Mary’s son James, in 1566, Darnley himself was murdered at Kirk o’ Field. Mary and her new companion, the Earl of Bothwell, were suspects. After Mary married Bothwell, the Scottish nobility rose against them and imprisoned the queen at Loch Leven Castle. The nobles forced Mary to abdicate (give up her throne), leaving Moray to rule on behalf of the baby king, James VI.

Mary escaped from imprisonment in 1568. She raised an army, which was defeated at Langside. After the battle, she fled to England. She wanted Elizabeth to help restore her to the Scottish throne. A civil war in Scotland continued until the defeat of Mary’s supporters, the Marians, in 1573. This marked the end of the possibility of a Catholic revival in Scotland. Elizabeth held Mary prisoner for nearly 19 years and eventually, in 1587, had her executed.

James VI came to the throne as an infant. He did not take control of his kingdom until the 1580’s. James was an intelligent and able monarch who worked hard to maintain peace in his kingdom. But James often came into conflict with the new Presbyterian church, which was governed by a General Assembly and laymen rather than bishops. James believed in the authority of bishops and wanted to appoint them himself. He also believed in the divine right of kings, while some church leaders rejected this and insisted that the church had superior authority.

The combined kingdoms.

James VI was careful not to offend Elizabeth. He even accepted his mother’s execution with little protest. When Elizabeth died in 1603, James VI was her closest relative and succeeded her as James I of England. He also moved to England. Because of his fairness in dealing with Scottish and English interests, his succession was untroubled. The union of England and Scotland had few benefits other than the restoration of order in the Border counties, the counties near the boundary between England and Scotland. James became increasingly isolated from the political and religious situation in Scotland. He visited his native land only once, in 1617, for a stay of several months. At this time, James pushed through a group of religious reforms that became known as the Five Articles of Perth. The Presbyterian General Assembly accepted these reforms under pressure, but many congregations deeply resented the Five Articles.

The English Civil War.

James did not challenge the Church further, but his son Charles I was not so wise. In 1637, he tried to impose on Scotland a version of the Book of Common Prayer, used by the Church of England, which incorporated the detested Five Articles of Perth. His attempts caused the Scottish Presbyterians to sign the National Covenant in 1638. This document voiced the Presbyterians’ objections to the English king’s involvement with Scottish church matters. Supporters of the Covenant were known as Covenanters. Their opposition to Charles’s policies led to riots and armed uprisings in Scotland. The Scots organized armies that marched across the English border and on to Newcastle, where they cut off coal supplies to southern England. To buy off the Scots, Charles had to raise money by reviving the English Parliament. His action started a chain of events that led to the English Civil War.

In 1643, during the civil war, the Covenanters and the English Parliament signed the Solemn League and Covenant. This agreement promised Scottish military support for the Parliament against Charles in return for the Presbyterian reform of the English Church. The joint Scottish and English forces defeated the king’s forces at Marston Moor in July 1644. The decisive factor that brought Charles’s defeat was the rise of the New Model Army. This professional force had as one of its commanders a landowner named Oliver Cromwell.

Fighting between supporters of the king and English and Scottish troops continued until 1646, when Charles surrendered to Scottish troops. The Scots insisted that Charles agree to allow Presbyterianism in England, but Charles refused. The next year, the Scots turned him over to the English Parliament for a large ransom.

In November 1647, Charles escaped to Carisbrooke Castle, on the Isle of Wight. Some Scots entered negotiations with Charles to restore him to the throne in return for his granting their demands. The king agreed to allow a three-year trial of Presbyterianism in England if the Scots would help restore him to the throne. War broke out between Scottish and English forces in 1648, but it was soon over. Cromwell routed the invading Scots at Preston on August 17, and the army put down Royalist uprisings elsewhere.

A special court condemned Charles to death. He was beheaded in 1649. Charles’s execution worsened relations between the Scots and Cromwell’s supporters in England. The Scots gave aid to Prince Charles, the son of King Charles I, who returned to England to claim the monarchy. But Cromwell defeated him at the Battle of Worcester in 1651, and he fled England again.

The Restoration.

Under Cromwell, who ruled England in the 1650’s, Scotland became virtually an English province. In 1660, the English Parliament restored the monarchy, and Prince Charles returned to England to be crowned King Charles II in a process called the Restoration. The English government controlled the Scottish government through the king’s Privy Council, a panel of royal advisers. The Scots reluctantly accepted bishops again, after being without them for many years.

When Charles II died without a legitimate heir in 1685, his younger brother James became king as James II of England and James VII of Scotland. James, a Roman Catholic, wanted to restore Catholicism and absolute monarchy in England. James broke the law by appointing Roman Catholics to state and church posts. He tried to win the support of Protestant Nonconformists, who refused to conform to the official church, by issuing a Declaration of Indulgence. The declaration ended discrimination against Roman Catholics and Protestant Nonconformists. Seven bishops protested, and James imprisoned them in the Tower of London.

The Glorious Revolution.

James had two Protestant daughters. Many members of Parliament felt that they could tolerate James, provided that one of his daughters would succeed him. But in 1688, James had a son, James Francis Edward Stuart, whom he planned to bring up as a Roman Catholic. This frightened some politicians. They invited a Protestant Dutch prince called William of Orange, husband of James II’s elder daughter, Mary, to invade England. William landed in Dorset and marched on London, where the people welcomed him. James fled to France, and William of Orange became King William III. People called the events of 1688 the Glorious Revolution because the change of rulers came almost without bloodshed.

The Scottish Convention of Estates, a group temporarily ruling in place of the Scottish Parliament, invited William and Mary to rule Scotland. The couple accepted in 1689. But not all Scots favored this succession. The Jacobites, a group that included Highlanders and Episcopalians (members of a branch of the Anglican Church), remained loyal to the exiled King James. These supporters of James defeated government troops at the Battle of Killiecrankie in 1689, but a year later they were defeated at Cromdale.

The Act of Union.

Relations between the Scots and the English Parliament deteriorated in the 1690’s. Perhaps as much as 15 percent of the Scottish population starved during a famine that struck Scotland from 1695 to 1699. The Scottish economy was in a disastrous condition.

Meanwhile, a union between Scotland and England was proposed as part of the attempt to find a solution to the question of succession in case Queen Anne, William III’s successor, died without an heir. A majority of Scots in Parliament voted for the terms of the union. Although favors or bribes might have influenced some of these members of Parliament, many recognized the economic benefits the union would have for Scotland. The Act of Union, passed in 1707, joined the kingdoms of Scotland and England into what it called the Kingdom of Great Britain, often shortened to “Great Britain” or “Britain.” The Scots dissolved their own Parliament and sent members to the British Parliament instead. Scotland received 45 seats in the House of Commons and 16 in the House of Lords. Scottish laws, the Scottish education system, and the Church of Scotland remained unchanged.

The union of 1707 was not popular in Scotland, and a large number of riots occurred after it was announced. The Jacobite risings, which were attempts to restore the exiled Stuart family to the thrones of England and Scotland, occurred in 1715 and 1745. The Jacobites fought to install James Francis Edward Stuart as King James VIII. Their efforts failed to reverse the union, and gradually most Scots came to accept it. The 1745 rising was led by James’s son, Charles Edward Stuart, also called Bonnie Prince Charlie. Although Charles was welcomed by the Highlanders, his rebellion received little support in the Lowlands. The Stuart cause collapsed after government forces crushed the Jacobites in a battle at Culloden in 1746. The Scottish clan system was destroyed.

Economic prosperity

gradually returned to Scotland after the Act of Union as Scotland became part of the British trading empire. Glasgow became the main center of the tobacco trade with the American colonies. Benefits from the union also provided money for investment in agriculture and industry. As a result, the Scottish linen industry grew rapidly. The traditional Lowland agriculture began to change to meet the needs of a growing industry. English technical skill and money led to the establishment of the cotton industry, which began the drive toward industrialization.

The Enlightenment,

also called the Age of Reason, was a period in history when philosophers emphasized the use of reason as the best method of learning truth (see Enlightenment). In Scotland, the Enlightenment began in the second half of the 1700’s, although its beginnings can be traced back further. It was largely based in the urban areas and was connected with the universities and clubs that existed in Scotland’s leading cities. Edinburgh became the Scottish center of the Enlightenment, but Aberdeen and Glasgow also made important contributions in the fields of philosophy, science, and the arts. Such thinkers as the philosopher David Hume and the economist Adam Smith introduced new ideas for a society based on rational thought and liberal economic policies.

The Industrial Age

By the middle of the 1700’s, a period of rapid industrialization called the Industrial Revolution was underway in Britain. Industry was slower to develop in Scotland than in England. Nine out of 10 Scottish manufacturing workers in 1825 were employed in weaving or cloth manufacturing. It was only after 1840 that the growth of an economy based on iron, and later steel, shipbuilding, coal, and engineering, developed. The mix of inventive genius and plentiful supplies of cheap labor, fuel, and raw materials provided a great boost to Scottish industries.

Urbanization

(the growth of cities or towns) occurred quickly during the 1800’s in Scotland. The rapid, unplanned growth of the towns resulted from the flood of migrants moving in from the Scottish Highlands and Ireland in search of work. Major social problems resulted. Housing was scarce, and massive overcrowding occurred. Disease spread easily among the slum dwellers and the poor. Scottish authorities introduced housing reforms and public health measures. But as late as 1913, two-thirds of the Scottish population lived in homes of only one or two rooms.

In 1845 and 1846, the potato crop failed in Ireland, beginning what is known as the Great Irish Famine (1845-1850). The immigration of many Irish Catholic people to Scotland after the famine increased social divisions and tensions. The Catholic Irish were confined to low-paid, unskilled work and faced discrimination. These tensions caused large numbers of Scots to leave. Between 1841 and 1931, 2 million Scots emigrated.

The government put into effect several measures of social reform in response to the urban crisis. The Poor Law of 1601, which regulated the treatment of beggars to provide them with relief, was reformed in 1845 to provide more support for unemployed or injured workers. But it remained difficult for the able-bodied poor to get help. The 1872 Education Act took control of elementary schooling away from the Church of Scotland. These laws weakened the power of the Church of Scotland because they gave the government more control of social life.

Important political changes

resulted from the industrial and social changes of the 1800’s. The growing working and middle classes pressured the government to give them voting rights. The middle classes gained the right to vote in 1832, but the urban working classes of Scotland had to wait until 1868 before their claims were recognized. A series of other legislative measures widened voting rights still further by 1914, although women did not gain the right to vote until 1918. Scotland’s voters in the 1800’s were generally more liberal than voters in England during that time.

During the mid-1800’s, several political parties developed in the United Kingdom. The Liberal and Conservative parties emerged from loose political groupings after 1867. Support for the Liberal Party was based on a widespread dislike for the ruling elite in the countryside. Irish immigrants supported the Liberals, particularly when William Gladstone, the Liberal prime minister, came out in favor of Irish Home Rule (self-government for Ireland) in the 1880’s (see Home rule). Gladstone’s support of Irish Home Rule split the Liberal Party in the 1880’s and began the slow decline of the party in Scotland. In 1912, the Conservatives allied themselves with the Liberal Unionists to form a new party, the Conservative and Unionist Party.

The first moves to form an independent labor party emerged in the late 1880’s, but the Labour Party was not formed until 1906. The skilled workers separated from the Liberals because of the party’s refusal to appoint working-class candidates and its lack of interest in problems of overcrowding and other housing issues.

The emergence of modern Scotland

Industrial growth and depression.

The economy of Scotland experienced an important transformation during the early 1900’s. As the naval rivalry between Germany and the United Kingdom intensified, demand for the products of Scottish industries increased. The Scottish shipyards and heavy industries, particularly on the River Clyde, flourished.

At the beginning of the 1900’s, a socialist movement emerged in Scotland. The movement for labor unions and other forms of worker representation began to gain strength. The Scottish Trades Union Congress was formed in 1897 and had over 40,000 members by the early 1900’s.

World War I.

After the United Kingdom entered the war on Aug. 4, 1914, thousands of Scots volunteered to join the United Kingdom’s forces. Scottish regiments joined Allied forces at the Battle of the Somme in 1916 as well as in other battles in France, Egypt, Greece, and Palestine. The fighting lasted until 1918, when the Allies finally defeated Germany. More than 145,000 Scots were killed in the war. See World War I.

The war brought hardship to all areas of the United Kingdom. Returning soldiers soon faced housing shortages and mass unemployment. Much of the demand for heavy industry ended with the war, and the shipbuilding and coal industries declined. The economic crisis prompted 400,000 Scots to emigrate in the 1920’s.

The Great Depression,

a worldwide economic slump, began in 1929. The Depression left many people jobless and poor. In 1931, Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald formed a government of Labour, Conservative, and Liberal leaders to deal with the emergency. The government increased taxes, abandoned free trade, and cut its own spending. But the world economic situation grew worse, and Scotland and the rest of the United Kingdom could not escape the effects of the Great Depression. Scotland was especially hard hit, with over one-fourth of the labor force out of work in the early 1930’s.

World War II and its aftermath.

Troops from Scotland fought in World War II (1939-1945) alongside the other troops from the United Kingdom. The River Clyde was a vital port in the war, and Scottish factories produced millions of tons of military supplies. In March 1941, German bombers attacked Glasgow in an attempt to destroy the shipyards and other industries that supported the Allied cause in the war. The German bombs killed more than 1,000 people, destroyed the homes of many more, and damaged some of the factories. The United Kingdom, the United States, the Soviet Union, and the other Allies finally defeated Germany and Japan in 1945. More than 57,000 Scots were killed in the war.

Scotland’s heavy industry declined sharply after World War II. Resource shortages and foreign competition wiped out coal, shipbuilding, and steel industries. The Scottish economy moved away from heavy industries and toward services industries. Scotland’s unemployment rate was higher than the average for the United Kingdom as a whole.

Social programs.

The Labour Party won a landslide victory in 1945. The party had campaigned on a socialist program. Clement Attlee became prime minister, and the Labour Party stayed in power until 1951. During those six years, the United Kingdom became a welfare state. The nation’s social security system was expanded to provide welfare for the people “from the cradle to the grave.” The Labour government introduced a national health care system and also began to nationalize industry by putting private businesses under public control. The nationalized industries included the Bank of England, the coal mines, the iron and steel industry, the railroads, and, for a short time, the trucking industry.

These programs helped to ease the problems of poverty and poor health in Scotland. Large-scale public housing programs in the 1950’s and 1960’s eased the problem of run-down, overcrowded housing, but problems of poverty and unemployment remained.

Political change

in Scotland in the 1900’s included important changes in the power of the three main political parties. The Labour Party gained great importance. The party had only a handful of Scotland’s parliamentary seats in the early 1900’s but became the dominant political force in Scotland by the end of the 1900’s. The Liberal Party was greatly reduced from its height of power at the beginning of the 1900’s. The Conservatives peaked in the mid-1900’s, winning just over 50 percent of the vote in the 1955 general election in Scotland. But by 2000, the party had lost all of its Scottish seats in the British Parliament.

Nationalism

gained importance in Scottish politics beginning in the early 1900’s. Most nationalists called for home rule within a federal British state. Scottish leaders made several attempts in the 1920’s to pass legislation on home rule, but none succeeded. The economic depression of the 1920’s and 1930’s and the events in Europe that led to World War II limited nationalist support.

In 1934, the National Party of Scotland and the Scottish Party merged to form the Scottish National Party (SNP), which was committed to securing Scottish independence. The party at first had little success in elections, winning only a few victories in by-elections (special elections to fill empty seats) in the early 1940’s. In the mid-1900’s, Scottish voters grew discontented with the government’s handling of the economy and turned to the SNP. In a by-election in 1967, the SNP won a seat traditionally held by the Labour Party in Hamilton. Although Labour won Hamilton back in the 1970 general election, support for the SNP began to grow, particularly in new towns and among the young and voters alienated from the main parties. The SNP’s success reached a peak in the second general election of 1974, when the party won 11 seats and 30 percent of the vote in Scotland.

In response to the increase in Scottish nationalism, the Labour government established the Royal Commission on the Constitution in 1969 to recommend policy on devolution in the United Kingdom. The commission’s report, called the Kilbrandon Report after the chairman of the committee, Lord Kilbrandon, recommended establishing assemblies for Wales and Scotland. As a result, Scottish leaders held a referendum (vote of the people) on devolution in 1979, but it failed to pass.

Discoveries of oil in the North Sea in the late 1960’s and early 1970’s brought investment and many jobs to Scotland. Aberdeen became known as the oil capital of Europe.

Although support for the SNP decreased after the failed referendum, increasing dissatisfaction with the Conservative governments of the 1980’s and 1990’s again led to an increase in nationalist support. As these movements grew in strength, the SNP also became more powerful. The Labour government that came to power under Prime Minister Tony Blair in 1997 recognized the strength of the nationalist movements in Scotland and Wales. Blair organized a referendum on self-government in both places.

In 1996, Queen Elizabeth II authorized the return of the Stone of Scone to Scotland. The stone is to be returned to London temporarily when a British monarch is crowned.

The people of Scotland voted to create their own Parliament in a referendum on Sept. 11, 1997. The Scotland Bill was introduced in Parliament in January 1998 and became law as the Scotland Act 1998 in November of that year. The members of the Scottish Parliament were elected on May 6, 1999, and convened for the first time on May 12. The Parliament took up its full legislative powers on July 1, 1999.

In 2013, the Scottish Parliament lowered the voting age from 18 to 16. The move preceded a referendum on Scottish independence scheduled for September 2014. Following a highly publicized campaign, the Scottish people voted on September 18 to keep Scotland within the United Kingdom. Approximately 55 percent of the voters cast ballots against independence.

Recent developments.

The SNP came to dominate Scottish politics in the early decades of the 2000’s. SNP leader Alex Salmond served as Scotland’s first minister (head of government) from 2007 to 2014. Nicola Sturgeon took on the role in 2014, and Humza Yousaf succeeded her in 2023. The United Kingdom’s departure from the European Union (EU), known as Brexit, was completed in 2020. Uncertainty over Brexit led to renewed calls for independence and to support for increased partnership with the EU. In the 2020’s, Scotland faced a number of challenges, including the COVID-19 pandemic, a struggling economy, and problems with its health and education systems. The SNP’s John Swinney succeeded Yousaf as first minister in 2024.