Uttarakhand, << oo tur uh KAHND >> (pop. 10,086,292), is a state in northern India. Uttarakhand has some of the highest mountains in India. It has lush forests and many places of extraordinary beauty, as well as important pilgrimage sites (places visited for religious purposes). The Indian government created the state, then called Uttaranchal, in November 2000 from the northern districts of the state of Uttar Pradesh. In 2006, Uttaranchal changed its name to Uttarakhand.

People and government

People.

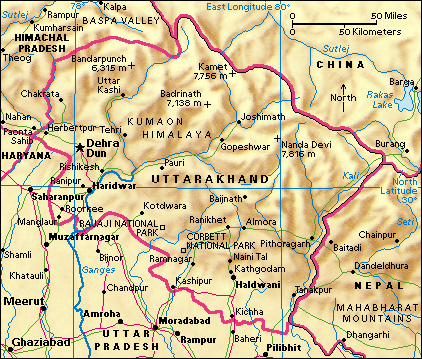

The northwest part of Uttarakhand is called Garhwal, and the southeast part is called Kumaon. Garhwal and Kumaon were once separate kingdoms. Most of the people of the north and west hill regions are known as Garhwalis, and most of the people of the south and east hill regions are known as Kumaonis.

About 85 percent of the population of Uttarakhand are Hindus. A number of small ethnic groups known as tribes live in the state, including the Bhotias, Jaunsaries, and Gujjars. Many people from other parts of India have also settled in Uttarakhand. In the southern district of Udham Singh Nagar, most of the people are Punjabis, and there are a large number of Bengalis as well.

Most people in Uttarakhand speak Hindi. However, Kumaoni and Garhwali each have more than 1 million speakers.

Poverty is widespread. Many of the people in Uttarakhand are too poor to afford adequate food, shelter, and medical care.

Government.

When the state was created, Dehra Dun, in western Uttarakhand, was selected to serve as the temporary state capital. Many of the people in Uttarakhand would prefer a capital in the center of the state, but a final decision on the issue has not been made.

The head of state is the governor, whom the president of India appoints to a five-year term. The chief minister is in charge of the administration of the government. The chief minister selects a cabinet of ministers from the state legislative assembly. The assembly has 70 members, who are elected by the citizens of the state.

Uttarakhand elects five members to the Lok Sabha, the lower house of the Indian Parliament. The Uttarakhand state assembly nominates three representatives to the Rajya Sabha, the upper house.

An official called the collector is responsible for administration at the district level. Gram panchayats (elected village councils) are in charge of local administration. Some panchayat seats are reserved for women.

Land

Land features.

Most of Uttarakhand is hilly or mountainous. Three ranges of the Himalayan mountain system cross the state—the Shiwalik, the Kumaon, and the Zaskar. The tops of the highest peaks in Uttarakhand are permanently covered with snow. The name Himalaya means the House of Snow, or the Snowy Range, in Sanskrit.

A narrow plain lies on the border between Uttarakhand and Uttar Pradesh. The southern part of this region is called the terai. The terai was once a densely forested area covered by sal trees and tall grasses. Much of the terai has been converted to agricultural use. Farther north is the bhabhar, which consists of coarse, loose gravel from the mountains.

The Shiwalik mountain range is the lowest of the ranges in Uttarakhand. It runs diagonally along the southwest edge of the state, beyond the terai and bhabhar. The Shiwaliks vary in height from 1,000 to 3,300 feet (300 to 1,000 meters) and have numerous valleys.

The Kumaon Himalaya lies north of the Shiwalik range and also runs diagonally across the state. Although it crosses both the Kumaon and Garhwal regions, geographers refer to the entire range as the Kumaon Himalaya range. In Garhwal, this range is called the Garhwal Himalaya. It has many high peaks, including Nanda Devi (25,643 feet or 7,816 meters) and Badrinath (23,419 feet or 7,138 meters). The Ganges and Yamuna rivers have their sources in the Kumaon Himalaya range.

The Zaskar range forms the border between Uttarakhand and the Tibet region of China. Kamet, which rises to a height of 25,446 feet (7,756 meters), is the highest peak in the Zaskar range.

Climate

varies widely throughout the state due to the differences in elevation. The terai, bhabhar, and low-lying valleys share the hot, tropical climate of the neighboring Northern Plains. But the highest peaks in the state are always covered in snow and ice.

The warmest and driest period of the year lasts from March to June. At low elevations, average temperatures during this period range between 81 and 91 °F (27 and 33 °C) but often climb higher than 104 °F (40 °C). Temperatures in other areas fall as altitude increases. The average temperature at low elevations in January is 52 °F (11 °C), but it dips well below 32 °F (0 °C) at high elevations.

Much of the state receives from 40 to 80 inches (100 to 200 centimeters) of precipitation (rain, melted snow, and other moisture) each year. Most of this precipitation falls during the monsoon season, which starts about the middle of June and lasts through September. In steep or thinly forested areas, heavy rains often cause flooding, erosion, and mud slides as water rushes down mountain slopes. During the cool or winter season from October to March, many areas receive heavy snowfall.

Animals and plants.

Uttarakhand has a large variety of wild animals, including bears, deer, elephants, mountain goats, snow leopards, and tigers. There are six national parks in Uttarakhand, most notably Corbett, Nanda Devi, and Rajaji. The state also has seven wildlife sanctuaries, including Askot, Gobind, and Kedarnath.

The high, mountainous areas of Uttarakhand have forests of pine, spruce, and deodar (East Indian cedar). Forests of sal trees grow at lower elevations. In many areas, the original variety of trees has been replaced by a single fast-growing species to provide fuel and timber.

Rivers and lakes.

Two of India’s most important rivers, the Ganges and the Yamuna (or Jumna), originate in Uttarakhand. The Ganges, the greatest waterway in India, begins in northwestern Uttarakhand, at an ice cave called Gomukh, which means the cow’s mouth. The Yamuna, a major branch of the Ganges, starts at the Yamunotri glacier, also in northwestern Uttarakhand.

Other rivers in the state include the Sarda and the Ramganga, a tributary of the Ganges. Where the Sarda flows along Uttarakhand’s eastern border with Nepal, it is known as the Kali. It enters the Ghagara River, another major branch of the Ganges, in Uttar Pradesh.

Almost all the large lakes in Uttarakhand are in the Naini Tal district. Tal means lake in Kumaoni. Lakes in this area include Naini Tal, Bhim Tal, Malwa Tal, Naukuchiva Tal, and Saat Tal.

Economy

Agriculture

is the main occupation in Uttarakhand. The chief crops of the state include millet, potatoes, rice, sugar cane, and wheat. Small quantities of fruit are also grown. Less than 15 percent of the land in Uttarakhand can be cultivated. The Udham Singh Nagar district in the south and the Dehra Dun district in the west are the most productive agricultural areas in the state. However, most farmers in Uttarakhand have small farms, and many find it difficult to produce enough to meet their own needs.

In the hill areas, farmers have created terraced fields—that is, level strips of land cut out of the hillsides, on which crops can be grown. In addition to growing crops, some farmers also raise cattle, sheep, water buffalo, and other animals.

Commercial logging companies, illegal timber cutters, and local populations have cut down much of Uttarakhand’s forests. Many areas suffer from a shortage of firewood, the most important cooking and heating fuel in the state. Most of the forests in Uttarakhand are owned by the government. Many forests are jointly managed by the state forestry department and local village forest councils, called van panchayats. The van panchayats help determine which trees in the forest can be cut down to meet local needs. They also oversee the gathering of forest products, such as medicinal plants and resin, and participate in reforestation projects.

Manufacturing.

Uttarakhand has little industry. A government-owned pharmaceutical factory operates in Rishikesh. A heavy electrical equipment plant near Haridwar produces generators and industrial electric motors. Uttarakhand’s many mills process the crops grown in the state, such as rice and sugar cane. Villagers work on handicrafts, woolen clothing, and fruit processing.

Transportation.

The transportation network in Uttarakhand is weak. There are railroad stations at Dehra Dun, Haridwar, Kathgodam, and Ramnagar. But railroads do not extend far beyond the borders of the neighboring states. Dehra Dun and Pantnagar have airports. Connections by road are poor, especially at greater altitudes. But good roads lead to the major pilgrimage locations in the mountains.

Mining.

Uttarakhand has few mineral reserves. Copper, dolomite, gypsum, limestone, marble, phosphate, and soapstone are found in small quantities.

Tourism

is the main source of revenue for the state. Thousands of people make pilgrimages to the many places in Uttarakhand that are considered holy by Hindus. The four most important pilgrimage destinations are Badrinath, Gangotri, Kedarnath, and Yamunotri, which are high in the mountains. Every 12 years, Haridwar hosts the Kumbh Mela, a Hindu religious festival that is one of the largest gatherings of people anywhere in the world.

The hill resorts of Almora, Naini Tal, and Mussoorie are popular destinations for summer visitors. Corbett National Park, a wildlife resort with tigers and elephants, is also popular. Mountaineers and hikers come to Uttarakhand to trek across its rugged terrain. Skiing and river rafting are other tourist activities in the state.

History

The first inhabitants of what is now Uttarakhand were the Kols. Their descendants may be the lower-caste groups in the state today. The Kols were followed by the Kiratas, who had earlier settled the eastern Himalaya. After 1500 B.C., the Khasas settled in Uttarakhand. The Khasas are a branch of the people known as Aryans, who migrated to India from Central Asia. Most of the people of Uttarakhand claim descent from the Khasas.

For most of its history, the region was divided into many small chiefdoms, with rulers exercising control only over local areas. These rulers probably paid tribute (money or gifts acknowledging another group’s authority) to the Mauryan Empire (about 324-185 B.C.). From the 200’s B.C. until the A.D. 200’s, the Sakas and then the Kunindas ruled most of Uttarakhand. Between A.D. 320 and 500, the region probably came under the control of the Gupta Empire.

From about the 600’s to the 1100’s, the Katyuri dynasty established control over a large area of the Himalaya from the dynasty’s capital in Baijnath. The Katyuris built many temples during the time they ruled. Near the end of the 1100’s, attacks by the Mallas, from what is now Nepal, ended Katyuri control of the region.

In the 1350’s, Ajaiya Pal of the Pala dynasty conquered a number of local chiefs in Garhwal. His descendants soon controlled all of Garhwal. In Kumaon, members of the Chand dynasty began to expand their power in the early 1400’s. By the 1500’s, they ruled all of Kumaon and moved their capital from Champawat in eastern Kumaon to Almora. Beginning in the late 1500’s, the armies of the Pala and Chand rajahs (princes or minor kings) fought several wars and frequently raided each other’s territories.

Kumaon paid tribute to the Mughal Empire, which ruled most of India from the 1500’s to the 1700’s. Although the Mughals gained control of the area around Dehra Dun, Garhwal retained its independence. In the 1740’s and 1750’s, the region was raided by the Rohillas, a group of Afghan warriors who had established a kingdom on the Ganges plain south of the terai.

In the early 1790’s, the Gurkhas, from what is now Nepal, conquered Kumaon and attacked Garhwal. Although forced to retreat by a Chinese attack on their home territory, the Gurkhas continued to raid Garhwal throughout the 1790’s. In addition to the Gurkha raids, Garhwal experienced famine in the mid-1790’s. A massive earthquake struck the area in 1803, causing great damage. A large Gurkha force invaded in 1803 and conquered Garhwal by 1804. The Garhwal ruling family fled the region, and Rajah Pradhuman Sah was killed leading an army against the Gurkhas. The Gurkhas ruled the region harshly. Many people were sold into slavery for failing to pay taxes.

While in exile, Sudershan Sah, the son of Pradhuman Sah, requested help against the Gurkhas from the British East India Company. Though privately owned, the East India Company acted on behalf of the United Kingdom. By the early 1800’s, the company was the dominant power in India. Gurkha territory already bordered the area controlled by the British in what is now Uttar Pradesh state. The Gurkhas launched a number of raids on East India Company territory, and the British declared war on the Gurkhas in 1814. The Gurkhas, despite being vastly outnumbered, initially repelled the British forces. But the British defeated the Gurkha army in Garhwal and Kumaon in 1815.

Under the Treaty of Sagauli in 1816, the Gurkhas gave Kumaon and most of Garhwal to the British. The rajah of Garhwal, who had agreed to give the British these territories in return for British assistance, received control of a small area in the northwest, called Tehri-Garhwal. The new British territories were combined to form the Kumaon Commissionery of the East India Company’s North-West Provinces.

In 1858, the British government decided to rule India directly and assumed control of the East India Company’s possessions. In the 1860’s, because of its cooler climate, Naini Tal became the summer residence of the government of the North-Western Provinces.

Both the British and the rajahs of Tehri-Garhwal allowed wide-scale commercial exploitation of the region’s forests. Under the Forest Act of 1865, all of India’s forests were made the property of the government of British India. Large areas of forest in Uttarakhand were cleared of trees, and local rights to forest produce and forest-grazing areas were limited. Frequent protests against the government’s policies occurred. Although the protests were mostly peaceful, a rebellion over the issue was violently put down by the local ruler of Tehri-Garhwal in 1930.

Following Indian independence from the United Kingdom in 1947, Garhwal, Kumaon, and Tehri-Garhwal became part of the state of Uttar Pradesh. An invasion of northern India by the Chinese in 1962 prompted the Indian government to improve the road network that extends into the mountains of the region.

Commercial timber cutting, local forest rights, and environmental damage caused by widespread deforestation continued to create controversy. In 1973, a group of peasants, mainly women, organized a movement of resistance against commercial timber companies in Garhwal. As the loggers came to chop down the trees, the women clung to them. The movement became known as the Chipko (cling) movement. The movement soon spread to Kumaon. Bowing to pressure in 1983, the Indian government banned the felling of trees growing in areas 3,300 feet (1,000 meters) above sea level or higher. However, new environmental threats emerged in the 1980’s, as mining activity increased and the government sought to build huge dams to generate hydroelectric power.

In 1979, activists formed the Uttarakhand Kranti Dal (Uttarakhand Revolutionary Organization) with the aim of gaining statehood for the mountain areas of Garhwal and Kumaon. The name was adopted from ancient Hindu literature, which called the region Uttarakhand, meaning Northern Territory. Supporters of the statehood movement felt that the Uttar Pradesh government neglected the people of the mountain areas.

In 1991, a devastating earthquake in the region killed over 1,500 people. Supporters of statehood pointed to delayed relief and reconstruction operations as evidence of government neglect. Tensions erupted again in 1994, when the Uttar Pradesh government sought to increase the percentage of government jobs and academic scholarships for low-caste people in the region. Upper-caste Hindus, who make up a majority of the population, objected to these efforts.

In 1996, the Indian government announced its commitment to creating a new state named Uttaranchal. National government leaders chose the name because they felt that Uttarakhand sounded like an area independent from the rest of India. In Hindi, the suffix –khand means a place apart, but -anchal means a part of a larger whole.

In July 2000, supporters introduced the Uttar Pradesh Reorganization Bill, calling for the establishment of Uttaranchal, in the Lok Sabha. The Lok Sabha and Rajya Sabha passed the bill in August, and Uttaranchal was created on Nov. 9, 2000. In 2006, Uttaranchal changed its name to Uttarakhand.

In June 2013, days of heavy rain caused landslides and flooding that killed thousands of pilgrims making an annual visit to Hindu shrines in Uttarakhand. Officials estimated the death toll to be around 4,700 based on the number of people missing.