Buchanan, << byoo KAN uhn, >> James (1791-1868), served as president in the critical years just before the American Civil War. Many issues divided the nation, but slavery was the main cause of argument. Buchanan personally opposed slavery. But, as president, he insisted that the Constitution of the United States protected slavery and that the laws must be obeyed. Moreover, Buchanan’s determination to admit Kansas to the Union, despite massive evidence of intimidation and fraud by proslavery forces there, fractured the Democratic Party. It also lessened Buchanan’s credibility as a national leader and accelerated the advance of the Republican opposition.

When 7 of the 15 slave states seceded in 1860 and 1861, Buchanan refused to use force to hold them in the Union. He hoped they would grow discouraged and return to the Union. He felt that a warlike policy might cause all the slave states to secede, making a peaceful settlement impossible. His policy delayed the Civil War until after his successor, Abraham Lincoln, took office.

The only president who never married, Buchanan was almost 66 years old when he succeeded his fellow Democrat, Franklin Pierce. The public respected him for his faithful service in both houses of Congress, as secretary of state, and in important diplomatic posts. People found him reserved at first meeting, but warm and friendly when they knew him better. His nephew described him as “tall—over six feet, broad shouldered, with a portly, dignified bearing …; his eyes were blue, intelligent, and kindly, with the peculiarity that one was far and the other near sighted, which resulted in a slight habitual inclination of the head to one side. …”

The storm over slavery gathered during Buchanan’s administration. Abolitionist authors aroused New England. The Lincoln-Douglas debates in Illinois focused attention on the moral wrongness of slavery. Adding to the national unrest, wild speculation in western land and railroads brought on an economic panic. Many banks, factories, and railroads failed. Thousands of unemployed workers stood in bread lines for free food.

On the brighter side, women wore lavish outfits with hoop skirts, and beaver hats trimmed with ostrich feathers. Pony express riders carried the mail through the expanding West. Queen Victoria sent greetings to Buchanan over the first Atlantic cable. In winter, Americans went riding in horse-drawn sleighs and sang a new tune called “Jingle Bells.”

Early life

James Buchanan was born on April 23, 1791, in a log cabin in Stony Batter, near Mercersburg, Pennsylvania. His father, James Buchanan, Sr., had come from Ireland in 1783 at the invitation of an uncle living near Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. He married Elizabeth Speer, a neighbor of his uncle, and opened a country store.

Young James, the second of 11 children, learned arithmetic and bookkeeping while working at his father’s store. The boy studied Greek and Latin under the village pastor. He attended Dickinson College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, and was expelled for breaking the rules. But he returned to take high scholastic honors.

After graduation in 1809, Buchanan studied law in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. He began to practice law there in 1812. His careful business habits enabled him to build a fortune which at his death totaled $300,000.

Political and public career

Soldier and legislator.

Buchanan supported the Federalist Party, which favored a strong central government. Like most Federalists, he opposed a second war with the United Kingdom. But when the War of 1812 came, he volunteered as a private to help defend Baltimore. He served in the Pennsylvania legislature for two terms, from 1814 to 1816.

Tragedy.

Buchanan did not seek reelection to the legislature in 1816, choosing instead to build his law practice in Lancaster. Buchanan became interested in Ann Coleman, the daughter of a wealthy Lancaster iron manufacturer. In 1819, Ann and James reached an understanding to marry. But a quarrel—never specified—provoked Ann to move to Philadelphia, where she died several months later. Gossips suggested that she had committed suicide, though there was no proof of this. Buchanan was deeply affected by Ann’s death. In following years, the confirmed bachelor mentioned Ann Coleman as the one true love of his life. Partly to get away from the scene of his romance, he returned to politics.

Congressman and diplomat.

Buchanan ran successfully for the United States House of Representatives in 1820. During his 10 years of service there, he abandoned the dying Federalist Party. In 1824, he supported the presidential candidacy of Andrew Jackson, a hero of the War of 1812. He continued his support even after Jackson was defeated by John Quincy Adams. Jackson was elected president in 1828. He appointed Buchanan minister to Russia in 1831 as a reward for his loyal support. Buchanan, a man of simple tastes, did not enjoy the formalities of the court of Czar Nicholas I. But he achieved results. In 1832, Buchanan negotiated the first trade treaty between the United States and Russia.

Senator.

Buchanan sailed home in November 1833. In December 1834, the Pennsylvania legislature elected him to fill a vacancy in the United States Senate. He served there until 1845. Buchanan became one of Jackson’s leading supporters and served for a time as chairman of the committee on foreign affairs. He tried to prevent debates over slavery, supporting instead Southern-sponsored measures to block antislavery petitions that began surfacing in the Senate in the mid-1830’s.

In 1844, Buchanan’s supporters in Pennsylvania mentioned him as a “favorite son” candidate for the Democratic presidential nomination. Buchanan withdrew his name before the convention met. Democrat James K. Polk won the election and offered Buchanan the post of secretary of state. Buchanan accepted and resigned from the Senate in 1845.

Secretary of state.

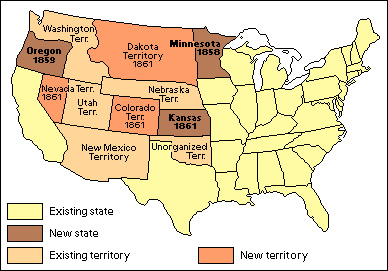

While Buchanan was secretary of state, the country acquired much new territory. As one of his first tasks, he completed the steps needed to make Texas a state. This action angered Mexico, which had never recognized Texan independence. Negotiations for a peaceful settlement failed, and the Mexican War resulted (see Mexican War ). As a result of the war, the United States acquired vast new territories in the Southwest.

At this time, the United States and the United Kingdom jointly occupied the Oregon region. President Polk claimed that the United States should control the entire region. Buchanan steered negotiations with the British and eventually agreed to a compromise line that forms the present Canadian boundary. See Polk, James Knox (“Oregon fever”) .

Minister to the United Kingdom.

The Whig Party regained the presidency in 1849, and Buchanan retired to Wheatland, his estate in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. In 1852, he pursued the Democratic presidential nomination. But Franklin Pierce won the nomination and the election. He appointed Buchanan minister to the United Kingdom.

In London, Buchanan tried for two years to modify the Clayton-Bulwer Treaty of 1850. This treaty provided that neither nation should occupy territory in Central America. After the treaty had been signed, the British claimed that it did not affect possessions they already held. The Americans replied that they would not have ratified the treaty if they had known this exception. Buchanan tried to get the British to give up these possessions, but failed. See Clayton-Bulwer Treaty .

Buchanan strongly supported U.S. expansion. In 1854, he helped write the Ostend Manifesto, one of the Pierce administration’s key initiatives. This document recommended that the United States should offer to purchase Cuba from Spain. It warned the Spaniards that the island might be seized if disorders ever threatened peace in the United States. Americans condemned the manifesto after newspapers reported, not quite correctly, that Buchanan had advised the president to seize Cuba if Spain would not sell it. See Ostend Manifesto .

Election of 1856.

Many leading Democrats became unpopular as presidential candidates because they had supported the Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854 (see Kansas-Nebraska Act ). But Buchanan had been in London when Congress passed this bill and had taken no stand on it. He returned from the United Kingdom in April 1856, and the Democrats nominated him for president the next month. They chose John C. Breckinridge, former Kentucky congressman, for vice president. The Republicans nominated two former senators, John C. Frémont of California and William L. Dayton of New Jersey. Nativists, known as “Know Nothings” or “Americans,” nominated a ticket of former President Millard Fillmore and Andrew Jackson Donelson, a former minister to Prussia.

The Democrats appealed to the desire of conservatives to preserve the Union. The party tried to avoid the slavery question. The Republicans openly fought slavery, and used campaign posters with such slogans as “Free Speech, Free Press, Free Soil, Free Men, Frémont and Victory!” The Know-Nothings could not agree on a position on slavery, emphasizing instead the need to restrain immigration. In a hotly contested election, Buchanan fell short of a popular majority but won a large electoral majority.

Buchanan’s administration (1857-1861)

The struggle over slavery

continued with increasing intensity throughout Buchanan’s administration. He tried to unite Democrats from the North and the South by balancing his appointments to public office. But many people felt that he favored the Southerners. At White House social functions, Southerners often outnumbered Northerners. Buchanan’s forceful support of the Dred Scott Decision seemed further to hint at Southern favoritism (see Dred Scott Decision ).

Buchanan’s actions on statehood for Kansas convinced still more people that he favored the South. For three years, North and South had argued over whether Kansas should be admitted to the Union as a free or a slave state. Buchanan had endorsed the principle of popular sovereignty, which held that the people of a territory should vote whether or not to allow slavery in the territory.

In 1857, proslavery settlers in Kansas drew up the Lecompton constitution, which would have permitted slavery in the new state. It was submitted to Kansas voters for approval. But the antislavery settlers refused to vote on the grounds that the Lecompton document was a fraud. Buchanan insisted that Congress accept the Lecompton Constitution for Kansas. Senator Stephen A. Douglas, an Illinois Democrat, opposed this procedure. Largely because of his influence, Congress refused to approve the constitution. Congress sent the constitution back to the people of Kansas in 1858, and they overwhelmingly rejected it. See Kansas (“Bleeding Kansas”) .

Buchanan’s stand on the Kansas question greatly angered the North. In the congressional elections of 1858, Northern candidates opposed to the president won a majority in both houses. The hostile Congress rejected Buchanan’s program to enlarge the army and navy, build a Pacific railroad, and develop canals and roads across Panama and Nicaragua. On the other hand, Buchanan vetoed several bills, including one to give free homesteads to settlers on western land.

Foreign affairs.

Buchanan developed firm policies in foreign affairs. His experience as a diplomat helped him establish better relations with the United Kingdom. The problem of British possessions in Central America was solved when the United Kingdom signed treaties with Nicaragua and Honduras that Americans approved.

Such disorder existed in Central America that European nations threatened to use troops to protect their citizens there. Buchanan urged Congress to intervene to keep order. Otherwise, he said, Europeans would intervene in defiance of the Monroe Doctrine (see Monroe Doctrine ). This stand foreshadowed the “Big Stick” policy of President Theodore Roosevelt. But Congress refused to allow Buchanan to carry out this policy.

Life in the White House.

The gloom of the White House during Franklin Pierce’s administration gave way to a brilliant social life when Buchanan took office. Buchanan, who never married, asked his niece and ward, Harriet Lane, to serve as his hostess. Under her guidance, one reception and ball followed another. Buchanan added a conservatory to the White House to provide flowers for these affairs. The most spectacular parties centered around the visit of the Prince of Wales, later King Edward VII of the United Kingdom. The prince brought such a large party that Buchanan had to sleep in a hallway to provide proper quarters for his guests.

Election of 1860.

By 1860, neither Northern nor Southern Democrats considered Buchanan for renomination, nor did he wish it. Southern Democrats nominated Vice President Breckinridge for president, and Senator Joseph Lane of Oregon as his running mate. Northern Democrats chose a ticket of Senator Stephen A. Douglas and former Senator Herschel V. Johnson of Georgia. The Constitutional Union Party named Senator John Bell of Tennessee and former Senator Edward Everett of Massachusetts. Abraham Lincoln of Illinois and Senator Hannibal Hamlin of Maine led the Republican ticket to victory in the election.

Prelude to war.

Buchanan faced the gravest responsibility of his career during the period between Lincoln’s election and inauguration. South Carolina seceded from the Union on Dec. 20, 1860, and on Feb. 4, 1861, met with six other slave states to form the Confederate States of America.

Buchanan declared that there was no “right of secession,” as Southerners claimed. But he also pointed out that the Constitution provided no legal way to prevent it. He recommended revising the Constitution in a way agreeable to both North and South as the only alternative to war. He said that the South’s refusal to accept defeat at the polls would destroy the tradition of self-government. But he felt it equally destructive to hold Southerners to citizenship by force.

Buchanan based his policy of cautious restraint on two beliefs. First, he felt that by keeping calm, he could retain the loyalty of the eight slave states still in the Union. Second, he believed that if left alone, the seven Confederate states would soon disagree among themselves and move toward reunion.

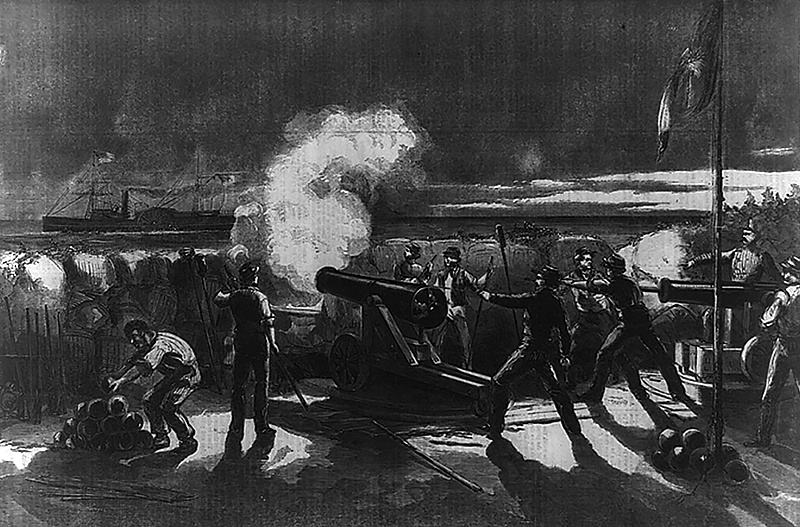

On Dec. 26, 1860, a small garrison of Union troops moved from Fort Moultrie to Fort Sumter, in Charleston Harbor. South Carolina sent commissioners to Buchanan to demand that the garrison be withdrawn. Buchanan refused to surrender the fort. His action caused two Southern Cabinet members to resign because they thought Buchanan was too hard on the South. Secretary of State Lewis Cass had resigned because he thought the policy not hard enough. Buchanan filled the three posts with men who were strongly loyal to the Union.

Buchanan agreed to let the steamer Star of the West try to relieve the hard-pressed garrison at Fort Sumter. South Carolinian batteries opened fire on the vessel on Jan. 9, 1861, and forced it to turn back. Buchanan refused to regard the attack on the steamer as an act of war, because no blood had been shed. For one thing, he did not have a large enough army to fight a war. More important, Buchanan wished to hand the government over to Lincoln with a chance for peace rather than a nation already at war.

During the month after Buchanan left office, he observed with satisfaction that Lincoln continued his policy. When Confederate troops fired on Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861, Buchanan wrote that Lincoln now “had no alternative but to accept the war instigated by South Carolina or the Southern Confederacy.” Buchanan publicly urged his fellow Democrats “to support the President with all the men & means at the command of the Country in a vigorous and successful prosecution of the war.”

Later years

Buchanan retired to Wheatland after Lincoln’s inauguration and followed the events of the Civil War. He devoted many months to writing a book in defense of his policies, Mr. Buchanan’s Administration on the Eve of the Rebellion. The book admitted no errors and insisted his presidency had been a complete success.

Enjoying his status as a retired statesman, Buchanan remained active in civic affairs and gave generously to charitable causes. He continued to entertain almost constantly. Harriet Lane and a nephew, James Buchanan Henry, lived with him during his last years.

Buchanan died on June 1, 1868. He was buried in Woodward Hill Cemetery in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. Wheatland has been restored and furnished as it was when Buchanan lived there.