Research skills are the skills of asking questions and finding answers. Life is full of questions. Most of us spend time each day asking questions and finding the answers to them. What is the quickest way to get to the museum? How much will a new computer cost? Who can fix that flat tire? Some questions are easily answered. But others are more difficult, and you may need help in finding the answers.

Research involves locating and retrieving information—answers to questions. Once you have the information, you can then work with it or communicate it to others. You may use the results of your research to help make a decision. Or you may communicate your research results in some schoolwork. Once you learn where to go or whom to ask to get answers to your questions, you have developed skills that you can use all your life. Research skills are useful in school, in a career, and in many everyday situations. Developing good research skills can help you find information more quickly and efficiently.

This article will help you become familiar with sources of information. You can learn how to find information in a library and elsewhere. You can also learn how to take notes so you can put your information to good use.

Getting to know the library

What the library provides.

For many people doing research, the library is the first place that comes to mind. Libraries—or media centers in many schools—contain more information than any one person could learn in a lifetime. That information is available in many forms. Books, periodicals (magazines and journals), and sources on the Internet make up the major part of most school and public libraries. Many libraries also have audiotapes and videotapes, brochures and pamphlets, compact discs (CD’s), films, maps, and photographs and prints. In addition, a library may have audiotape and videotape recorders, compact disc players, copiers, projectors, satellite dishes, and other equipment.

Whether you are using a small school library or the main branch of a major city library system, it is a good idea to get to know what materials and services the library provides. Some libraries provide online orientations to familiarize you with their services. Many libraries have brochures that describe what they offer. Browse around in the library and become familiar with the various sections.

Sections of the library.

Most libraries have two major sections—the general circulation section and the reference section. The general circulation section contains books and other materials that may be checked out of the library. In that section, you are likely to find all the fiction and most of the nonfiction books your library owns. The reference section has materials that, in most instances, cannot be checked out of the library. Most books in the reference section are not the kinds you would read from cover to cover. They include encyclopedias, dictionaries, atlases, and other reference works that play an important role in research. In some libraries, the reference section may consist of a few shelves. In other libraries, it may be a separate room or a series of rooms.

Librarians

themselves are an excellent resource when doing research. They can help you find an answer to a specific question, such as “When was Babe Ruth born?” Or they can direct you to sources that contain information on a broader topic; for example, the history of baseball. Some libraries have several librarians who specialize in different kinds of information and services. For example, a reference librarian would be more familiar with the library’s reference section than a children’s librarian would be. For more information about librarians, see Library (Assisting patrons) (Communicating information) .

Exploring the library catalog.

The library catalog is your guide to locating the resources of the library. It has information about every book the library contains and gives the book’s location. Catalogs may also include entries for CD’s, films, tapes, and other nonprint items. If your library does not include entries for nonprint items in its catalog, ask where such material is indexed.

Library catalogs take various forms, from traditional card catalogs to computer or online catalogs. It is important to learn how to use whatever type of catalog your library has. If you go directly to the shelves without checking the catalog, you may never know about books that have been checked out or are waiting to be reshelved. If you know your library has a particular book, but cannot find it on the shelves, the librarian may be able to see if it is waiting to be shelved. Most online catalogs show if an item is on the shelf or checked out. If the book has been checked out, you can ask that a “reserve” be put on it. You will then be notified when the book is returned.

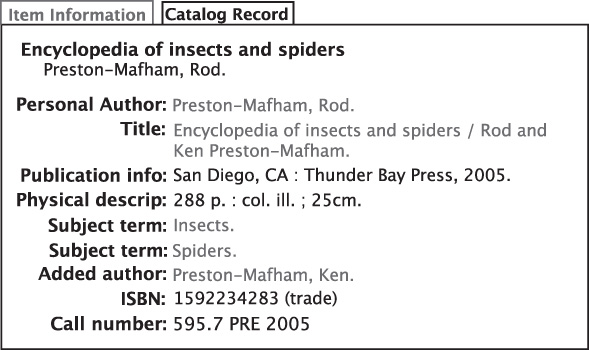

What catalogs can tell you.

Library catalogs contain a wide variety of information about books and other items. This information typically includes the title, subject, author, publisher and copyright date, number of pages, illustration information, and call number. Such information can help you decide how useful a particular resource will be. For instance, the publication date may be important in judging the value of the book for your purposes. If you are looking for up-to-date information, a book published 20 years ago may not be helpful. The catalog also tells you whether the book has an index or a bibliography (a list of books or articles about a particular subject). In addition, some catalogs provide a summary of the book’s content.

Understanding call numbers.

Call numbers are used to classify (group) nonfiction books and other materials according to subject area. Then the books are arranged on the shelves based on their classification. The call number of a book appears in the book’s catalog entry and on the spine of the book itself. The call number is important because it acts as the book’s “address.” It tells you exactly where to find the book on the shelves.

Most public and school libraries use the Dewey Decimal Classification System to classify nonfiction books. Some large libraries use the Library of Congress Classification System (LC). A letter and number code based on the author’s name appears below the Dewey or LC number.

If a call number has the letters R or REF in front of it, the book is in the reference section of the library. In most libraries, biographies are shelved together, separate from other nonfiction books. Biographies are arranged in alphabetical order according to the last name of the person the book is about. If only letters or the letter F appears instead of a call number, the book is a work of fiction. Such books are shelved separately in alphabetical order according to the author’s last name.

When you find an entry in the catalog for a book you want to use, copy down the call number, the title, and the author. Go to the appropriate section of the library. The call number should guide you to the book you are looking for.

Online library catalogs

allow users to search for information on books and other media through a computer system. Online catalogs in some libraries only store information about materials available on site. Other catalogs are networked, or connected, to other libraries and collections. You may be able to obtain materials from these collections through interlibrary loan.

You can access information in online catalogs by using the keyword search technique. For example, to find information about Siamese cats, type the keyword Siamese. The computer then searches the database for all “matches” or “hits” of that word. The keyword may appear anywhere in the title, subject, or description of the topic.

Using a specific keyword, such as Siamese, helps you find information quickly. Your search would be slower if a general word was used, such as cat. If your search turns up nothing, you then can try using a broader keyword. Likewise, starting any search with a general word such as war, history, geography, or science, will probably turn up too much material.

Words such as or, and, and not, are called Boolean operators. These operators connect keywords. Use or if you need to expand a topic or are unsure about how a topic is listed. For example, you can search under “Britain or United Kingdom” if you are uncertain about the proper word. And narrows the scope of your search. For information on the history of the United Kingdom, you would search under “United Kingdom and History.” Using not helps limit your search. For example, if you want information on the Reformation leader Martin Luther but not on the civil rights leader Martin Luther King, Jr., your search terms might be “Martin and Luther not King.”

Online catalogs also allow searches by author, by subject, and by title. In addition, many allow you to limit your search to materials published before or after a certain date or to certain types of materials. Most online catalogs indicate if material is in the library or checked out. With many online catalogs, you can print out information you need.

Paper card catalogs

are the traditional form of library catalog. The card catalog consists of one or more cabinets with drawers of file cards arranged alphabetically. For most books, there is one card under the author’s name, one under the book title, and one or more under the general subject. Some books may have additional cards for a joint author, an editor, a translator, or an illustrator.

The author card is called the main entry. The other cards are added entries. They look much like the main entry, but they have an additional line at the top. This line gives the title, the subject, or some other heading above the author’s name. The cards are arranged in alphabetical order, according to the words on the top line. Each drawer has author cards, title cards, and subject cards, all interfiled alphabetically.

The subject cards are the best place to begin library research if you do not have a specific title or author in mind. To find books on your topic, you first need to think of an appropriate subject heading. Try to think in specific terms, rather than using broad ideas. For example, look under HIMALAYA, rather than MOUNTAINS or DICKINSON, EMILY, rather than POETS. If you have trouble finding books on your topic, ask the librarian for suggestions on other subject headings to look under.

Other kinds of catalogs.

Some libraries have catalogs in book form, with separate volumes for listings by author, subject, and title. Other libraries store catalog information on microfilm.

In microfilm catalogs, printed material is photographed and greatly reduced in size, so that many lines fit onto a small piece of film. Special equipment enables the user to enlarge the film image so it can be read on a screen.

Reference and source materials

Kinds of reference materials.

You can find many answers to your research questions in reference materials. Some reference works, such as almanacs and encyclopedias, provide information directly. Other works, such as indexes and bibliographies, tell you where to find information. General reference works cover a variety of subjects. World Book is an example of a general reference work. Special or subject reference works, such as The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians and The Encyclopedia of the American Revolution, provide information on only one subject. Such reference works cover a subject in greater detail than general reference works.

Many reference books and indexes are available in electronic formats. These formats could include online sites accessed via the Internet or a CD-ROM (_C_ompact _D_isc _R_ead-_O_nly _M_emory). Many of these sources are in multimedia format. They supply photographs, graphics, sound, and video; information originally published in other sources such as newspapers or magazines; or articles in books.

Like the rest of the nonfiction collection, the reference section is arranged according to subject. Familiarize yourself with the part of the reference collection that contains materials for your research. Then you will be able to refer to them quickly when you need information.

Frequently used reference works.

Most libraries have hundreds or thousands of reference materials. You will not use all of them. But some works will become reliable sources of information that you turn to again and again. The most frequently used reference works include encyclopedias, yearbooks, almanacs, dictionaries, and periodical and newspaper indexes.

Encyclopedias

can be a good place to begin research. They contain thousands of articles on a variety of topics. Thus, the subject you are interested in is likely to be covered in some form. Reading an encyclopedia article can give you a good introduction to your topic. It can provide you with many of the facts you will need. The encyclopedia will also list related information, both encyclopedia articles and other sources.

Yearbooks

are annual supplements to encyclopedias. Together with yearly almanacs, they provide up-to-date statistics and other facts on many topics. These topics might include business, politics, sports, entertainment, foreign countries, and population. These sources can be useful for information about current events. Collections of yearbook articles can also be a good source of information on recent history. World Book Student and World Book Advanced include such articles covering nearly a century in their Back in Time feature.

Dictionaries.

Most people think of a dictionary as a source to use when they want to know how to spell or pronounce a word or learn what it means. But if you take time to become familiar with a good dictionary, you may be surprised at the other kinds of information you find. For example, it may contain information about grammar, word usage, writing style, and etymology (how words originated). Many dictionaries list foreign alphabets and words, common signs and symbols, and place names. Some print dictionaries show how to proofread a manuscript.

Periodical and newspaper indexes.

Magazines and newspapers are valuable sources of information, especially for topics of current interest that may not be covered adequately in books. They can also give you what people at the time thought of events, issues, and personalities. Periodical and newspaper indexes are the reference tools that can tell you where to find articles on your topic in such sources. Some online sources provide methods of searching newspapers and magazines, and enable the user to select and read articles of interest. Others, such as World Book Student and World Book Advanced, link relevant magazine articles to reference information.

Readers’ Guide to Periodical Literature

is the most widely used guide to magazine articles. It indexes articles from more than 400 leading nontechnical magazines. Readers’ Guide is issued several times a year in paperback. Each year’s issues are then reissued in a bound volume. The periodicals included may vary from volume to volume, so be sure to check the list that appears in the volume you are using. You will also need to find out which periodicals your library has in its collection. Readers’ Guide is also available online.

The entries in Readers’ Guide appear in alphabetical order by subject and author and, sometimes, by title. Abbreviations are used for many parts of the entry, including the name of the magazine, the date of the issue, the volume and number of the issue, and the page number where the article can be found. An explanation of the abbreviations appears in the front of each volume of the guide. Be sure to read it so that you can understand the entry. Here’s a sample entry for an article on employee health insurance:

- Employee health insurance Broken Promises [Retiree medical benefits] M. Andrews. graph il. Money v34 no5 p49-50 My 2005.

The entry tells you that an article titled “Broken Promises,” by M. Andrews, begins on page 49 of the May 2005 issue of Money Magazine. It discusses retiree medical benefits. The article is illustrated and has a graph.

In addition to Readers’ Guide, there are a number of specialized guides to periodicals, such as the Art Index and the Business Periodicals Index. These works may lead you to articles not indexed in Readers’ Guide.

The New York Times Index

is an index to the articles in The New York Times. Many libraries subscribe to this newspaper because it provides broad coverage of national and international news. Entries are listed alphabetically, mainly by subject.

Electronic reference materials

are carried by many libraries. The two most common electronic formats are online, where information from a remote computer is delivered via the Internet, and CD-ROM. Electronic sources provide information quickly. Many are also updated more frequently than printed materials. Some electronic sources provide video, sound, and motion in addition to text.

Keyword searching is used to find information in most electronic sources. Some sources also have a site map, menu, or table of contents.

Many reference works stored in electronic systems have information similar to that which occurs in a print version. Such works include dictionaries, the Bible, William Shakespeare’s plays, ZIP Codes and addresses, and Bartlett’s Familiar Quotations.

Electronic encyclopedias

store all the information found in a multivolume set of encyclopedias. World Book Student and World Book Advanced are electronic versions of World Book. They contain such encyclopedic information as text, maps and pictures; additional features from annual books and magazines covering recent events or history; and audio, video, animations and other multimedia information. Such encyclopedias as The McGraw-Hill Encyclopedia of Science and Technology are also available in electronic format.

Electronic periodical indexes

, such as InfoTrac, index hundreds of magazines and journals. In addition to bibliographic information, electronic indexes may include a summary of the article or the article’s full text. Most electronic periodical indexes are searched by using keywords.

The Internet

is a worldwide network of computers that has become a popular online information service. Government agencies, businesses, nonprofit organizations, and individuals provide free or fee-based access to their websites. Each site is a collection of information taken from other publications or produced specifically for online delivery.

Search features on the Internet allow keyword searching to find new websites or specific information. The Internet is especially useful when you are looking for information that changes frequently. For example, you might go to the website of a newspaper to search on a developing story in the news.

Before using the Internet, you should think about your information needs and your search strategy. There is generally a wealth of information on the Internet, but some of it is unreliable or of poor quality.

Getting what you need.

In most school and public libraries, you can go to the shelves directly to find the item you want. But in some large libraries, you will need to fill out a call slip and request the item from someone who works at the library.

Most libraries keep current issues of newspapers and magazines on shelves for easy access. Past issues may be kept as bound volumes or on microfilm. Bound volumes consist of all the issues for a particular period bound together in one volume. The volumes are put on the shelves by order of their date. On microfilm, pages are photographed and greatly reduced in size. The images appear on a reel or on a sheet called microfiche. A viewing machine enlarges the images and projects them on a screen so you can read the pages. Microfilm of newspapers and magazines is generally stored in file cabinets. As with books, you may be able to get bound volumes and microfilm yourself, or you may need to fill out a call slip. Libraries also subscribe to such databases as LexisNexis. These databases provide access to magazine, journal, and newspaper articles that are not freely available on the Internet.

Judging the value of reference and source materials.

After you have the references and sources you want, how can you judge if they are really useful? There are several factors to consider:

Scope of coverage.

Turn to a book’s index to see how much coverage your topic receives. If your topic appears on several pages, the work is worth checking carefully. A website may have an index or a search feature. You can use either one to see how much coverage there is on your topic.

Publication date.

If you are doing research in a rapidly developing field, such as computers, you will want the latest material available. But if you are dealing with a historical topic, such as the Korean War, the publication date may not be as important. In a book, the publication date usually appears on the back of the title page. On a website, if the publication date is not available, spot check the website by searching on it for a recent event that you know of, such as the death of a famous person. If the site contains the current information, it is more likely that the rest of the site is kept up-to-date.

Authoritativeness.

Is the author well known in the field? Has the author written other works on this subject? The book jacket or introduction can help you find out.

Are there citations, appendixes, or other indications of careful scholarship? If you are consulting periodicals, it may be wise to avoid articles in popular magazines that are not recognized as authoritative. If you have any doubts about the appropriateness of a particular magazine article, check with your teacher or a librarian to see if it would be acceptable.

If you use a newspaper article as a source, keep in mind that the information presented is perishable. Ongoing events are covered in newspapers on a day-to-day basis as more information comes to light. As a result, comprehensive coverage on a topic is seldom available in one newspaper article.

If you are using the Internet to find sources, one way to ensure authoritativeness is to use websites with a “.org,” “.gov,” or “.edu” extension in the address of the site. These extensions are used for the official websites of organizations, government agencies, and educational institutions.

Websites with “.com” extensions are generally owned by companies or individuals, and are often less authoritative. For example, if you wanted to find reliable information about Glacier National Park, it would be best to go to the U.S. National Park Service government website, rather than a personal Web page entitled, “My trip to Glacier National Park.” Although the latter website may have some interesting information, it is likely to be narrower in focus, to be opinion-based, or to omit important information.

Bias.

Does the author have an apparent bias that could hamper the objectivity of the book or article? For example, if you are doing research on the 1967 Arab-Israeli war, a book, article, or website on the subject by either an Arab or an Israeli author might be biased. Although it could be an interesting source to include among others, it would be unwise to use it as your main source.

Edition.

Check the title page or copyright page to see if the book is a first edition or a revised edition. If there have been several editions, it could mean that the book has been well received and is considered a reliable source. Try to use the latest edition available.

Reading level.

Skimming a few pages should tell you if a book, article, or website will be easy to understand or if it is chiefly for scholars in the field. Does the author use a lot of technical language? Are unfamiliar words defined?

Special features.

Check to see if the book, article, or website has illustrations, maps, charts, a glossary, a list of sources, or other helpful features. Some websites provide animations, simulations, and video and audio files. Such features may suggest that the source is a useful one.

Overall quality.

Judging the quality of a book is relatively easy. If it is in a library, it will have been carefully chosen. However, there are thousands of websites and judging their quality can be more difficult.

The presentation of information on a website does not necessarily determine the reliability of that information. However, to minimize the time spent researching your topic, you should avoid sites that are poorly organized or slow to use because of advertising or irrelevant graphics.

There are certain things to look for in a website. Some questions to ask are: Is the layout of the website logical and easy to understand? Is it easy to find your way around the site? Is biographical information provided about authors who publish articles on the website? Is background and contact information available about the organization that controls the website?

Getting the most out of a reference work.

To make full use of a reference work, take time to familiarize yourself with its organization before you plunge in to search for information. See if the book or website has an introductory section on how to use the work, a key to abbreviations, or similar helpful information.

Consult the table of contents to get an idea of what the reference work covers and how the material is organized. The table of contents lists chapter titles and such features as illustrations and maps. Do not neglect to check any material that appears in the front and back of the book. An introduction and author’s foreword can have valuable information. Appendixes may include charts, tables, the text of documents, and author’s notes. Lists of sources can provide you with titles of additional books or websites to check.

When you are ready to find specific information, turn to the index or search feature. The index or search feature offers quicker access to information in the book or website than the table of contents offers. Most reference books have one general index, which lists proper names, titles, and topics together. Some works have several indexes—for example, an author index, a title index, and a subject index. Some websites offer more than one method of searching. Always check the index or search feature to find out where the information you want is.

To use an index or search feature, think of the word that most clearly identifies your topic. For information on the Nile River, for example, look under “Nile,” not “River.” For information on the presidency of Nelson Mandela, look under “Mandela,” not under “presidency.”

After you have located the proper pages, skim the text quickly to see if it has the information you need. Look at any headings; the first, or topic, sentence of each paragraph; and concluding summaries. This method should help you spot main ideas. If the source has useful information, fill out a source card, read the text carefully, and take notes. For more information on taking notes and preparing source cards, see the following sections.

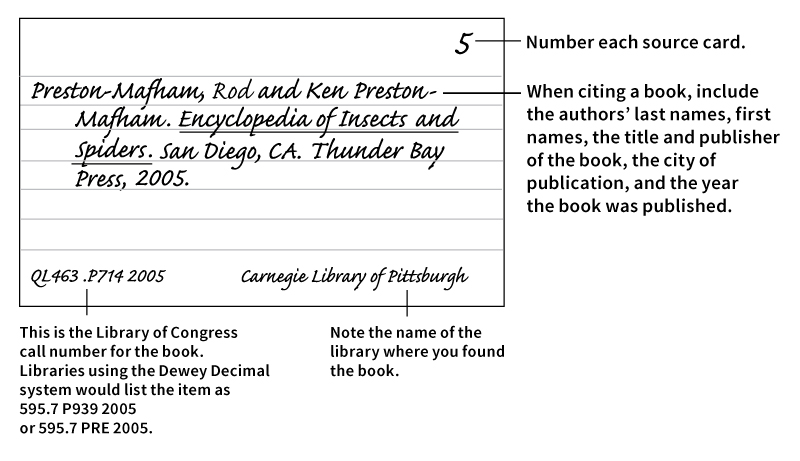

Preparing source cards

You should prepare a source record for every source you consult—books, magazine and newspaper articles, pamphlets, DVD’s, CD’s, and so on. Source records can be handwritten cards or entries in a word-processed document. In each case, a record should contain all the information you will need later when you prepare a list of sources for your report.

To prepare source cards, use standard-sized cards, ruled or unruled, and write in ink on one side only. Use one card for each source you consult. That way, it will be easy to arrange the cards in alphabetical order later.

Use the same format for your source records that you will use for the final list of sources. See Writing skills (Preparing a list of sources) . If you number each source record at the top, you can use this number in your notes to identify the source of the note. It is also a good idea to include in the source record the call number of the book and the library where you found it. Then if you need to check the source again, you will know exactly where to find it.

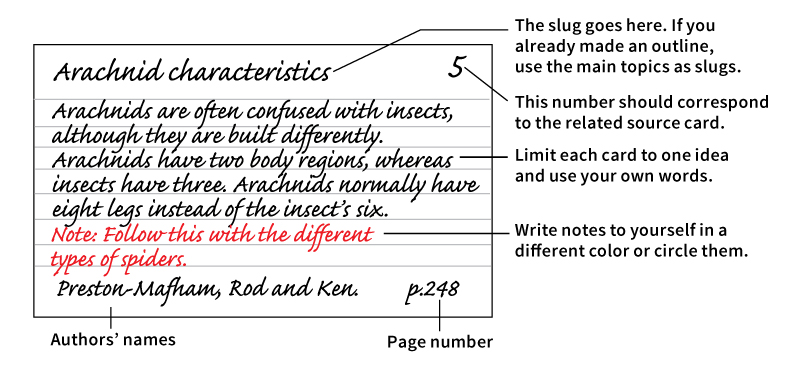

Taking notes

Good research depends on good notes. The information you find in reference works must be clearly and accurately recorded in your notes. Only then can the information become part of a well-organized and well-written report. There are various ways to go about taking notes. It is important to find a system that works well for you.

One of the best systems uses note cards. Take notes in ink, on one side of the card only. Put only one item—fact, quotation, or idea—on each card. This method will make it easier to arrange and combine your notes in any order you want. Write the source number (taken from your source card) in the upper right-hand corner of the note card. Include the page number of the source in case you need that information for a footnote later. Write a short heading—called a _slug—_at the top of the card to identify the topic or subtopic the note refers to. If you have prepared an outline, the slug should correspond to a heading in your outline.

Before you write or type a note, evaluate the material you have read to make sure the information is worth recording. If it is, do not just copy it word for word. Paraphrase or summarize the information. You may also wish to add personal reactions or other comments on your notes. If so, circle them, write them in a different color, or use some other method to distinguish them.

Generally, make notes in your own words because they reflect your thinking, not someone else’s. You should use direct quotes only when the author’s words are particularly striking, when you want to refer to an expert’s knowledge or opinion, or when you want to hold an author accountable for a particular idea or statement.

Using other sources

The library and the Internet are by no means the only sources for research material. People and places near and far can provide you with information that will make your research more complete and more interesting.

Writing or e-mailing for information.

Government agencies and business and professional associations can be important sources of information. By contacting such organizations, you may be able to get reliable statistics and other facts that would be difficult to track down elsewhere. For example, if you were writing a report about literacy in Canada, it might be helpful to e-mail or write to Canada’s provincial departments of education for the most recent statistics on literacy. Furthermore, many organizations publish a variety of pamphlets and other materials that you can use for research. Many of these materials are free or inexpensive.

Your library will have directories with addresses of government, business, and other organizations. Searching the Internet is another source of addresses.

When you write for information, keep in mind that some groups are better equipped than others to handle requests. Make your request specific and reasonable. If you are requesting information by mail, include a self-addressed, stamped envelope for the reply. Most important, do not assume that the reply will arrive by the time you need it. It might not. Be prepared to use information from other sources if necessary.

Conducting an interview

can be an effective way to get facts and personal viewpoints that add special interest to your report. Begin with a courteous phone call or letter identifying yourself and requesting an interview. Specify the sort of information you need. Make yourself available at a time that is convenient for the person you are contacting.

Before the interview, read background material about the topic. That way, you will be better able to ask intelligent questions and follow-ups. Prepare a list of questions ahead of time.

Listen carefully during the interview. Take notes on important points and be careful to write direct quotations exactly as they are said. Be sure to ask permission to use a direct quote. Ask for clarification of points you do not understand and the spelling of unfamiliar terms or names. A tape recorder or digital voice recorder can eliminate the need for taking lengthy notes by hand. But again ask permission beforehand. Some people object to being recorded or “freeze” when you begin recording.

Before you leave the interview, be sure to write down accurately the subject’s name, position or title, and place of business. You will need this information for your list of sources. Do not forget to thank your subject at the end of the interview. Also follow up with a thank-you note.

Conducting a survey

is another way to get unique material. You can ask people questions in person or develop a questionnaire. In either case, phrase your questions carefully so that people can respond easily and clearly. Surveys that use a “yes or no” or “for or against” format are the easiest to evaluate. You may want to include a “no opinion” category. Or you may prefer a format that allows for a range of opinion. Whatever method you choose, take care to record the results accurately.

Using television as a source.

Television documentaries, news programs, and interview shows can give you access to expert opinions and valuable information. If you watch a program as part of your research, be prepared to take careful notes. Be sure to note the name of the program, the network, and the date of broadcast for your list of sources.

Museums, art galleries, and historical societies

may enable you to explore your subject firsthand. For example, a report on the painter Vincent van Gogh could be enhanced by a visit to an art museum that exhibits some of his works. Many museums and other cultural centers have libraries or other research facilities open to the public. Check to see what your community has to offer that can help you understand your topic better.

Documenting sources

When preparing a report or research paper, it is important that you document (give credit to) the person whom you are quoting or whose ideas you are using. Presenting another person’s work or ideas as one’s own is called plagiarism. Plagiarism is unethical (morally wrong).

Citations tell readers where you found your information and where further information on the topic can be obtained. There are several different styles for citing research. Most styles involve notes—such as parenthetical citations or footnotes—within the text and a complete list of sources at the end of the document. The list of sources should contain all the books, articles, interviews, websites, and other sources that you used for your report or research paper.

For information on citations, see Writing skills (Preparing citations) .

Glossary

A selected list of terms and abbreviations commonly encountered in research.

- Abr. Abridged (shortened, not the full work); abridgment

- added entry The heading above the author line on a catalogue card. The card is filed by this entry.

- annotation A brief description of the content of a book.

- anon. Anonymous (author unknown)

- appendix A section that follows the text, containing material relative to but not essential to the subject.

- bibliography A list of books or other sources. May be general, selective, on a particular subject, or have a common theme, often annotated.

- bk., bks. book(s)

- c. or ca. circa, about. Refers to an approximate date (e.g., c. 1340)

- call number The classification number used to request a book.

- CD-ROM _C_ompact _D_isc _R_ead-_O_nly _M_emory. A small disc used to hold text, graphics, video, and sound for catalogues and reference works.

- cf. Confer; compare one source with another

- ch., chap., chaps. Chapter(s)

- class number The number by which a book is identified in a classification system (e.g., the Dewey Decimal Classification System or the Library of Congress Classification System). It indicates the subject matter of the book.

- col., cols. Column(s)

- continuation A work (e.g., The World Almanac) issued at regular intervals.

- copr.; © Copyright The copyright notice usually consists of the symbol © (with or without the word copyright) and the year in which the book was copyrighted. May apply to the entire work or only a part. It generally appears on the verso (back side) of the title page.

- cross-reference A reference to another entry. A see reference is to the preferred entry, the one under which the material appears; a see also reference is to related material.

- cumulate The contents of several volumes arranged into one volume.

- database Information stored in a computer.

- DVD A compact disc that can hold between 8 and 20 times as much information as a CD-ROM.

- documentation Support for a statement, as in a footnote or bibliography.

- e.g. exempli gratia, for example

- ed., eds. Editor(s); edition(s)

- ellipsis Three spaced periods used to indicate an omission. At the beginning of a sentence, it may or may not be followed by a capital letter; at the end of a sentence, it is preceded by a period.

- et al. et alii, and others

- et seq. et sequens, and following

- etc. et cetera, and so forth.

- f., ff. And the following (e.g., pp. 65 f.; pp. 64 ff.)

- fig., figs. Figure(s)

- front. Frontispiece (picture facing the title page of a book or of a section of a book)

- hot link In an electronic document, a text or illustrative link that, when activated, leads to another document.

- hypertext In an electronic document, highlighted text that, when activated, leads to another document.

- i.e. id est, that is

- ibid. ibidem, the same. In a footnote, refers to the book cited in immediately preceding reference. Ibid. takes the place of the author’s name, the title, and any identical material in the preceding footnote. The page number may differ.

- id. idem, the same. Used in place of the author’s name in additional references within a single footnote.

- il., illus. Illustrations, illustrator, illustrated

- infra See below; to be mentioned later.

- Internet A global computer network which links smaller networks, including government facilities, universities, corporations, and individuals.

- l., ll Line(s)

- LC Library of Congress

- loc. cit. loco citato, in the place cited. In a footnote, refers to a passage already identified when there are intervening references to other sources.

- main entry The catalog card that has full information about a book (the author card).

- MS., MSS. Manuscript(s)

- n., nn. Note(s)

- N.B. Nota bene, note well; take notice

- n.d. No date of publication or copyright given.

- n.p. No publisher given.

- network An information system that links several pieces of computer equipment and computer databases together for sharing information among many users and stations.

- no., nos. Number(s)

- op. cit. opere citato, in the work cited. In a footnote, refers to a previously identified work when a different part is cited and there are intervening references. Pages are included in the citation.

- p., pp. Page(s)

- paraphrase A restatement conveying the general meaning of the original.

- pass. passim, here and there; throughout the work (e.g., pp. 60, 81, et pass.)

- periodical Primarily a magazine, published at regular or irregular intervals.

- printing date The year the book is printed (usually appears on the title page). Not always the same as the copyright date.

- pseud. Pseudonym, a name other than an author’s real name; a pen name.

- pub. Published, publication

- q.v. quod vide, which see

- recto Right-hand page of a book; the back of a verso page

- rev. Revised, revision

- scope extent of treatment, coverage

- series title The collective title for a group of books.

- sic So, thus, in this way. Used within brackets in a quotation to show that an error is in the original: “It was to [sic] late.”

- sup., supp., suppl. Supplement

- supra See above; previously mentioned

- thesis The statement of purpose, the proposition to be explained or proved

- tr., trans. Translator, translation

- v., vol., vols. Volume(s)

- v. vide, see

- verso Left-hand page of a book; the back of a recto page

- viz. videlicet, namely. Introduces examples or lists.

- vs. Versus, against

- website A site location on the World Wide Web. Each website contains a home page, and may also contain additional documents and files. Each site is owned and managed by an individual, company, or organization.

- World Wide Web A system of Internet servers that support specially formatted documents, which can be easily accessed using a web browser. Not all Internet servers are part of the World Wide Web.

Dewey Decimal Classification

Used with permission of OCLC. All copyright rights in the Dewey Decimal Classification system are owned by OCLC. Dewey Decimal Classification, DEC, OCLA, and WebDewey are registered trademarks of OCLC. For more information, see http://www.oclc.org/dewey.

000 Computer science, knowledge & systems

- 010 Bibliographies

- 020 Library & information sciences

- 030 Encyclopedias & books of facts

- 040

- 050 Magazines, journals & serials

- 060 Associations, organizations & museums

- 070 News media, journalism & publishing

- 080 Quotations

- 090 Manuscripts & rare books

100 Philosophy

- 110 Metaphysics

- 120 Epistemology

- 130 Parapsychology & occultism

- 140 Philosophical schools of thought

- 150 Psychology

- 160 Logic

- 170 Ethics

- 180 Ancient, medieval, & eastern philosophy

- 190 Modern western philosophy

200 Religion

- 210 Philosophy & theory of religion

- 220 The Bible

- 230 Christianity & Christian theology

- 240 Christian practice & observance

- 250 Christian pastoral practice & religious orders

- 260 Christian organization, social work & worship

- 270 History of Christianity

- 280 Christian denominations

- 290 Other religions

300 Social sciences, sociology & anthropology

- 310 Statistics

- 320 Political science

- 330 Economics

- 340 Law

- 350 Public administration & military science

- 360 Social problems & social services

- 370 Education

- 380 Commerce, communications & transportation

- 390 Customs, etiquette & folklore

400 Language

- 410 Linguistics

- 420 English & Old English languages

- 430 German & related languages

- 440 French & related languages

- 450 Italian, Romanian & related languages

- 460 Spanish & Portuguese languages

- 470 Latin & Italic languages

- 480 Classical & modern Greek languages

- 490 Other languages

500 Science

- 510 Mathematics

- 520 Astronomy

- 530 Physics

- 540 Chemistry

- 550 Earth sciences & geology

- 560 Fossils & prehistoric life

- 570 Life sciences; biology

- 580 Plants (Botany)

- 590 Animals (Zoology)

600 Technology

- 610 Medicine & health

- 620 Engineering

- 630 Agriculture

- 640 Home & family management

- 650 Management & public relations

- 660 Chemical engineering

- 670 Manufacturing

- 680 Manufacture for specific uses

- 690 Building & construction

700 Arts

- 710 Landscaping & area planning

- 720 Architecture

- 730 Sculpture, ceramics & metalwork

- 740 Drawing & decorative arts

- 750 Painting

- 760 Graphic arts

- 770 Photography & computer art

- 780 Music

- 790 Sports, games & entertainment

800 Literature, rhetoric & criticism

- 810 American literature in English

- 820 English & Old English literatures

- 830 German & related literatures

- 840 French & related literatures

- 850 Italian, Romanian & related literatures

- 860 Spanish & Portuguese literatures

- 870 Latin & Italic literatures

- 880 Classical & modern Greek literatures

- 890 Other literatures

900 History

- 910 Geography & travel

- 920 Biography & genealogy

- 930 History of ancient world (to ca. 499)

- 940 History of Europe

- 950 History of Asia

- 960 History of Africa

- 970 History of North America

- 980 History of South America

- 990 History of other areas

Library of Congress Classification

This system of classification was devised by the Library of Congress in the United States uses 21 letters of the alphabet to represent the principal branches of knowledge. Subdivision is achieved by adding second letters and Arabic numerals up to 9999.

- A General works

- B Philosophy, psychology, religion

- C Auxiliary sciences of history

- D History: General and Old World

- E-F History: America

- G Geography, anthropology, recreation

- H Social sciences

- J Political science

- K Law

- L Education

- M Music and books on music

- N Fine arts

- P Language and literature

- Q Science

- R Medicine

- S Agriculture

- T Technology

- U Military science

- V Naval science

- Z Bibliography, library science, information resources