Aboriginal peoples of Australia << `AB` uh RIHJ uh nuhl >> are the first people who lived in Australia and their descendants. Australia’s Aboriginal peoples include peoples of mainland Australia, Tasmania, and some other nearby islands. The original inhabitants of the Torres Strait Islands off the northern tip of Queensland and their descendants, however, make up a separate collection of cultural groups known as the Torres Strait Islander peoples. Today, Australians often use the terms Indigenous peoples of Australia, First Australians, or First Nations peoples to refer collectively to the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples of Australia. The word indigenous means native. For additional information, see Indigenous peoples of Australia and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

The word aboriginal comes from the Latin phrase ab origine, meaning from the beginning. When spelled with a small a, the term aboriginal may refer to any people whose ancestors were the first people to live in a country. Australians use the term Aboriginal peoples (with an s) to emphasize the diversity of culture and language among several hundred Aboriginal groups, or peoples, from different parts of the Australian continent. The terms Aboriginal persons or Aboriginal people (without an s) are often used when discussing individuals rather than the groups. The Aborigines is not considered to be an acceptable term in Australia because of its connection to the country’s colonial past.

According to Aboriginal traditions, Aboriginal people have always lived in Australia. The ancestors of today’s Aboriginal peoples likely have lived in Australia for more than 65,000 years. Archaeologists (scientists who study the cultural remains left behind by past civilizations) estimate that these first people came by boat from Southeast Asia, the closest land that was inhabited by human beings at that time. By about 40,000 years ago, they lived in most of the country’s diverse regions, from the tropical rain forests to the central deserts (see Warratyi).

Scientists who have analyzed population characteristics and trends on the continent have suggested that there were between 500,000 and 1 million Aboriginal people living in Australia when European colonizers first reached the island continent in 1788. At that time, there were over 600 different groups, or tribes, and they inhabited every part of the continent. These different groups spoke hundreds of distinct languages and dialects and had varied beliefs and cultural practices.

Many white colonizers characterized the Aboriginal ways of life as undeveloped and primitive. As they did not value Aboriginal culture, they made little effort to understand it. They assumed that the Aboriginal peoples would either die out or assimilate (be absorbed) and live like Europeans. Today, however, many people realize that the Aboriginal culture was complex, sophisticated, and well-adapted to the environment in which the first Australians lived.

Europeans first encountered the continent of Australia and Aboriginal people in the early 1600’s, when the Dutch explored the Indian Ocean coast of Western Australia and sailed across the north looking for spices and trade goods. The Portuguese explored the Torres Strait area on their way to Papua New Guinea. In 1770, the famed British explorer James Cook in the Endeavour mapped the east coast. During the American Revolution (1775-1783), Britain had to discontinue the transportation (deportation overseas) of convicts from Britain to America. British officials decided that Australia, then called New Holland, would become a convict colony. The first colonists arrived in 1788.

The colonists brought with them European diseases that devastated Aboriginal communities, which had little or no immunity. Colonists took control of Aboriginal lands. The accompanying violence and the subsequent restrictions on access to traditional hunting grounds and resources also greatly reduced the Aboriginal population. This period has been described as a genocide during which whole families, lineages, and clans died. By 1921, Australia had only about 62,000 Aboriginal people.

From the time of the European colonization of Australia—described by Aboriginal people as an invasion—until the mid-1900’s, the government took control of many aspects of Aboriginal life. Government policies denied Aboriginal individuals many of the basic human and citizen’s rights that other Australians took for granted.

Today, there are about 815,000 Aboriginal people in Australia—some 3 percent of Australia’s total population. The nation’s Aboriginal peoples have tried in numerous ways to preserve cultural practices, languages, and ways of life from their ancestors. Some live in or near their own homeland and take care of it as well as they can. Some follow the religion of their ancestors.

For information on the general history of Australia, see Australia, History of.

Australia’s earliest people

Scientists believe that the ancestors of Australia’s Aboriginal peoples probably migrated there from Southeast Asia during the most recent ice age, a period in Earth’s history when ice sheets covered vast regions of land. During the ice ages, the seas grew smaller because more water was locked up in ice. When the people arrived in Australia, the sea level was lower and the Australian continent was up to one-third larger than it is today. Land bridges connected mainland Australia, what is now Tasmania, the Aru Islands, and Papua New Guinea in a land mass known as Sahul. The islands of Indonesia were separated by smaller stretches of ocean than they are now. During these periods of low sea levels, people could travel between islands in Southeast Asia but only rarely have to leave sight of land.

Although clearly these early travelers arrived by sea, no one knows what kind of boats the people used or how many people arrived in these first journeys. Archaeologists and geneticists (scientists who study genes and heredity) cannot say with certainty whether there was only one arrival or many, and they are still exploring what routes people took to get to Sahul/Australia.

Archaeologists have found ancient Aboriginal sites across Australia. These sites include locations at the Swan River in Western Australia and at Lake Mungo, Lake Tandou, and Talyawalka Creek in New South Wales. The sites date from 30,000 to more than 40,000 years ago. After people arrived in northern Australia, it could have taken them several thousand years to spread across the continent and learn to live in new environments. Scientists estimate that the ancestors of contemporary Aboriginal people must have arrived in northern Australia well before 40,000 years ago, the dates of the earliest Aboriginal sites in the south.

One ancient site in Australia’s Northern Territory provides early evidence for Aboriginal occupation. Archaeologists working at Madjedbebe, a rock shelter about 185 miles (300 kilometers) east of Darwin in the country of the Mirarr people, have excavated hundreds of stone tools and pieces of red ocher. Red ocher (also spelled ochre) is a common reddish mineral often used as a pigment. It plays an important role in ceremonies, where it is used as body decoration, and in rock art. The stone tools at the site included distinctive grinding stones and ground-edge hatchet heads. In 2017, scientists used sophisticated dating techniques that suggest the site was first occupied around 65,000 years ago.

Aboriginal people probably first established communities in the northern coastal areas, because the sea and coastal environments would have been familiar to them. They were probably comfortable in the tropical zones of northern Australia because the areas were similar to those of Southeast Asia. Many of the plants that grow in northern tropical Australia also grow in Southeast Asia. The people were also familiar with many foods, medicinal plants, and materials for tools found in Australia.

The animals of Australia were different from those of Southeast Asia, however. The sea barrier between Australia and other lands prevented the crossing of animals, so many unique species developed only in Australia. Giant kangaroos and other marsupials (mammals that carry their young in a body pouch) that are now extinct roamed the land.

The most recent rise in sea level began as the Pleistocene Epoch, an era of Earth’s history that lasted from 2.6 million years ago to 11,700 years ago, drew to a close. Between about 14,000 and 8,000 years ago, various parts of Australia were cut off from other land by water. Coastal areas that were inhabited when the seas were lower became covered with water as sea levels rose. Islands that formed during this sea rise include Tasmania in the south, and later Bathurst and Melville islands in the north. Australia’s coasts reached their modern shape about 6,500 years ago. After being cut off, the cultures of the people on those islands developed somewhat differently than those of the groups on the mainland. The people are still Aboriginal, but their histories and some aspects of their way of life are different. For additional information, see Aboriginal peoples of Tasmania.

Traditional Aboriginal society

The ability of Aboriginal people to live throughout the continent and through major climate changes shows that they had good skills in learning to adapt to new and changing environments. Prior to the European colonization of Australia, Aboriginal groups had complex social systems and beliefs that varied across the continent. Over time, they developed food gathering methods, fishing techniques, clothing, shelter, and languages unique to each area.

Those Aboriginal people who were nomadic hunter-gatherers traveled strategically, moving according to the seasons to locate food, water, and other resources by hunting or gathering. Eventually, some groups in southern Australia began to live in semi-permanent villages.

The oldest direct evidence for the presence of dingoes (semi-domesticated wild dogs) in Australia is from 3,000 to 3,400 years ago, but some scientists believe the animals could have arrived earlier. Australia had no other domesticated animals.

Social organization.

Territorial boundaries were not marked, but they were strictly observed. Clans interacted and traveled through the territories of other clans, but no group had the right to go into another’s lands without permission. The Aboriginal peoples divided the Australian continent and its coastal waters into defined areas that are known today as countries. Each country was inhabited by a group of people called a clan. Each clan had a common ancestor, and clan members considered one another family.

The idea of country (often spelled with a capital C) has always been important for Australia’s Aboriginal peoples. A clan’s country provided people with food and water. People had the duty of taking care of their country, and they believed that their country had a duty to take care of them, too. When Europeans pushed Aboriginal people off their clan’s country, the people faced serious problems. Aboriginal people had many relationships outside their own clan. They had relatives in other clans and could visit them. They had trading partners and religious partners who might support them for short periods. However, no other social group and no other country had the duty of taking care of the displaced individuals. The real security of their lives was in their own country. When they lost their country, they lost their security.

Clans did not live in isolation. They were part of larger groups, often called tribes. Members of tribes distinguished themselves from each other through their dialects. There were probably about 600 tribes within Australia in 1788, when the first Europeans began to colonize the continent.

Tribes that spoke closely related dialects often grouped themselves together under a term that identified their larger group, today sometimes called a nation. Usually, groups of tribes had much in common in addition to language. One important way in which they maintained their connections was through religious ceremonies.

Family groups.

Aboriginal people lived in family groups that consisted of parents and children with perhaps an aunt, an uncle, and one or two grandparents. In most parts of Australia, Aboriginal men hoped to have more than one wife, but not all men were successful. Unless a man had several wives, families were small. Most women raised only a few children. They cherished and spoiled their children until the young people were old enough to undergo initiation, a rite of admission into the Aboriginal society. After initiation, the children had to start learning law, adult skills, and the religious and practical knowledge that would enable them to become contributing adults and, eventually, respected elders.

The living site was described by European observers as a camp. An Aboriginal camp was a living area used for part of each year. The camp always had a fire as the focus, and the family put their sleeping area near the fire. The smoke on the horizon let other families know where they were. Women carried fire from one camp to the next.

Leadership

within the clan, tribe, and nation depended on age and knowledge. Aboriginal people gained knowledge through experience and participation in religious ceremonies. As individuals gained experience and learned more about the country, the seasons, the behavior of animals, and the locations of plants and water, they became elders. Elders guided younger people, made the major decisions, and decided what to do with persons who broke the rules.

The Aboriginal system of authority and leadership was organized to teach younger people and to keep troublemakers under control. Aboriginal leaders verbally disciplined people who broke the rules. Those who continued to break rules were given a beating. Those who still broke rules faced banishment from their group. Expelled individuals were forced to find food and shelter with others. However, most groups did not welcome troublemakers.

Food and water supplies.

Aboriginal people ate a large variety of foods, including animals, eggs, fish, seeds, fruits, tubers, insects, nuts, gum, honey, and flower nectar. Men were the main hunters of large animals, and women were the main hunters of small animals. Women did most of the food collecting and provided the majority of the clan’s day-to-day diet. Hunting for large animals took more time and was less successful on a daily basis. But large animals, such as kangaroos, provided meat to be shared with many people, which was an important social ritual. Along the coast, men hunted sea turtles and sea mammals called dugong, as well as large fish, such as sharks. Both women and men engaged in freshwater fishing. Men used pronged spears and various nets, including dragnets and drum baskets. They trapped fish by making dams or weirs (fences of broken branches put in a stream).

Aboriginal people relied on a wide variety of plants for food. In northern areas, they gathered wild fruits and seeds. These included native figs, green plums, and macadamia nuts. Yams and water chestnuts (also called spike rush) were important root vegetables that were abundant in the region. Aboriginal people would often place the root top back on the soil after a yam had been gathered. This gardening practice ensured that the plants would regrow in a particular patch of land and be available in the future.

In the drier central parts of Australia, people relied more on the seeds of native grasses and wattles, which could be gathered in great abundance. They also gathered desert yams and a wild plant called the bush onion. In southern Australia, roots and tubers were important plant foods. These included the rhizomes (roots) of bracken ferns, which contained a sticky starch; the roots of several kinds of lily; and several kinds of rushes and plants called yam daisies. Native mint and various gums, such as eucalyptus, were used for medicines. Sedges and rushes were also used to weave baskets and mats.

Australia is the world’s driest inhabited continent. Knowledge of water was important everywhere, but it was especially significant in the dry areas. Fresh water in the dry areas of Australia collects only temporarily. Rain fills up the billabongs (small pools or lakes) and claypans (shallow holes in the surface of the ground), and gets the rivers flowing. As the country dries out, the rivers cease to flow, the water holes shrink, and eventually there is little or no surface water left. People could live in a few of the driest deserts only part-time and had to leave when there was no water to be found.

Aboriginal people developed many important methods for finding and preserving water. They knew where to dig for water, and they knew the paths of underground rivers. Throughout the deserts and other dry areas, they dug wells. They put stone lids on claypans to keep the water in. They knew which trees stored water in the roots or in hollows, and they knew that some species of frogs stored water in their bodies. In stony country, they created and maintained rock wells. A rock well is a natural or man-made hole or depression into which underground water seeps or in which rainwater accumulates. People covered the wells with branches or rock slabs to reduce evaporation and keep out animals.

Vessels for carrying water were extremely important. The Aboriginal people had many different kinds of water containers. They sewed kangaroo skins to be watertight and constructed palm leaf containers, woven baskets, and large coolamons. A coolamon is a carved wooden container used to carry food and a variety of other items. A coolamon also was often used to carry a baby. Like many Australian tools, the coolamon had many functions.

Tools

included boomerangs, spears, digging sticks, grindstones, and carrying containers. Aboriginal people used a variety of small stone tools, including spear points, knives for cutting meat, and scrapers and chisels for making wooden tools and containers. People used boomerangs throughout most of the continent, although returning boomerangs were only found in eastern and western Australia. Nonreturning boomerangs were often larger than returning boomerangs. They were useful for hunting large animals, to punish troublemakers, or in warfare. In some areas, boomerangs were only used in ceremonies.

Aboriginal people avoided collecting large numbers of tools because it was inconvenient to carry the tools as they traveled. Instead, they made a few tools that could do many different jobs. Axes, spears, and boomerangs were men’s tools, and the digging stick, coolamon, and grindstone were women’s tools. The women used grindstones to grind seeds into flour or to crush nuts and other food. They also used grindstones for sharpening axes or grinding ocher.

Fire

was important to Aboriginal people. They used fire for cooking, for warmth, in hunting, and in the manufacture of many tools. They also used fire to clear the land by fire-stick farming. Burning the country at the correct time and in the correct way increased the productivity of many plants and the variety of animal habitats. The people burned land in small areas to create a patchwork where some areas had been burned recently and some burned longer ago. Each patch promoted the growth of certain plants or attracted certain animals. Scientists believe that this burning encouraged the development of a variety of types of animals and plants across most of the Australian continent. Aboriginal people also used fire in hunting to drive animals where the hunters could spear or club them.

Aboriginal people set their fires carefully to protect plants that would be damaged by burning. To burn the land skillfully, groups had to know their country well. It was a serious offense to burn other people’s country or to start a fire that burned out of control.

Clothing and shelter.

Aboriginal people wore little clothing. Their main article of clothing was a cord wrapped around the waist. People sometimes attached a shell or a piece of bark to the cord. Men and women decorated themselves with red and yellow ocher, pipe clay (fine white clay), and charcoal. They wore necklaces or armbands of feathers and shells, as well as hair decorations.

In cold areas, people made cloaks of animal fur and covered themselves for warmth. They protected themselves from cold nights by building shelters to block the wind, keeping small fires going, and sleeping with their dingoes. In areas where mosquitoes were a problem, some groups built houses on stilts. They kept a fire burning underneath their houses to make smoke that repelled mosquitoes. In areas where people did not use stilted houses, they slept inside small shelters made of tightly woven mats or bark. They sometimes hollowed out the floor of their house and filled it with soft grass or bark. In some areas, they lived in caves and rock shelters during the wet season. In northern areas, Aboriginal people used mats. Young and single men usually camped together on one side of the family area.

Religion.

Religious beliefs varied across the groups. According to some Aboriginal beliefs, ancestral beings created the world long ago during a period called the Dreaming, or Dreamtime. The story of the Dreaming explains the creation of the present-day landscape, animals, plants, and people. According to this belief, the ancestral beings, called Dreamings, traveled across the land, making and naming the places and people who would belong there. These ancestral beings never died but merged with the natural world. Some of the Dreamings went into the sky or into the ground, or merged into hills, rocks, or water holes. Others became plants, animals, and people. They were shape shifters who could change back and forth between their human shape and their animal shape. According to Aboriginal tradition, even the sun and the moon once were Dreamings and walked the earth. The Dreamings are immortal and live eternally in sacred sites.

Totemism.

According to Aboriginal beliefs, Dreamings created connections between groups and their country, and between groups of people and other animals and plants. The Dreaming tradition included a belief called totemism, which distinguishes tribes, clans, or families by linking them to a totem (natural object, usually a plant or animal). For example, some Aboriginal people are linked to the kangaroo totem and are, therefore, believed to be related to kangaroos. The kangaroo Dreaming is the ancestor of the kangaroo animals and of the kangaroo people. In some areas, a person’s totem was regarded as being of the same flesh as the person, and the person could not eat it. Men and women with a particular animal or plant as their totem were responsible for performing special ceremonies to increase the population of the animal or plant.

Songline

is one of the European names for the route the Dreamings followed. These tracks crossed great distances through the countries of many clans and tribes. Each clan and tribe was responsible for the part of the songline that ran through its country, and when people performed the Dreaming ceremonies, they tried to bring together people from many tribes along the songline. These people then performed the songs and dances that celebrated the Dreamings and renewed their power. Some of the ceremonies were for men only, and some were only for women. Aboriginal people believed that the proper performance of the ceremonies would bring the Dreamings into the world again to travel and do their creative work. In ceremony, therefore, the country was renewed.

Initiation rituals.

With age and experience, individuals became more knowledgeable, more senior, and more respected through participation in ceremonies. All Aboriginal boys and most Aboriginal girls had to go through a series of initiation rites. These rituals formally prepared young people for entry into adult life. Among the physical operations performed in some areas as part of the initiation were scarring the body and knocking out one or two teeth. For boys, circumcision (removing the skin that covers the head of the penis) and, in some groups, additional ritual cutting calledsub-incision were practiced.

Burial customs

varied among groups. In some regions, people buried their dead in the ground. In other areas, they placed their dead on specially constructed platforms or in trees. The traditional Aboriginal belief was that people were reincarnated (brought back to life in a new body) after death. They might be reborn as an animal before coming back in human form, but they expected that death would not be final. Most Aboriginal peoples believed that dead people also remained in their country as spirits. These spirits guarded the country against strangers and helped the living people get food and water. The collection of ancestral remains by anthropologists and museums has caused great distress for contemporary Aboriginal people who believe that the spirits cannot rest when they are removed from their country.

Arts and crafts.

The Aboriginal peoples of Australia created many forms of art. The most enduring artworks are the paintings and engravings on the walls of caves and rock shelters. The subject of the Aboriginal artwork is sometimes a recognizable form, such as a human being or an animal. In other cases, the subject is a circle or other pattern that could be understood only by those who were familiar with them. Aboriginal performance art included storytelling, dancing, and singing.

Painting.

To make paint, Aboriginal people crushed and ground red, yellow, black, and white pigments of varying shades and mixed them with water. Fingers, twigs, pieces of fiber, chewed stick ends, feathers, and human hair served as brushes. Hands and other objects were used to create stencil art by blowing pigment around them onto the rock face, thereby leaving a negative image.

Aboriginal rock art is one of the oldest continuous art traditions in the world, dating back at least 40,000 years. Archaeologists have discovered pieces of ocher buried deep in rock shelters that suggest Aboriginal people may have been painting even earlier. They might have used the ocher to make paint for rock paintings. They also used it to paint tools or their own bodies.

In North Australia, Gwion Gwion figures (previously known as Bradshaw figures after the explorer Joseph Bradshaw) are found in the Kimberley region of what is now Western Australia. Some of the rock paintings in this area have been dated between about 17,000 and 5,000 years old. Gwion Gwion figures are small, red paintings of human figures found on rocks throughout the Kimberley area. Dynamic figures are a series of stick figures, many wearing elaborate costumes, hunting, and doing other activities. These paintings are found in Arnhem Land, a region in the northeastern corner of what is now the Northern Territory. In both areas, scientists have also discovered paintings of the thylacine (also called the Tasmanian tiger or Tasmanian wolf). The thylacine probably became extinct in mainland Australia about 3,000 years ago, after the dingo was introduced.

Sculpture.

Aboriginal people in northeastern Arnhem Land made carved and painted human figures. In central Australia, Aboriginal people made a large variety of sacred objects of wood and stone. They used stone tools for cutting into stone or wood and for carving wooden objects.

Storytelling

among Aboriginal people sometimes drew on daily experiences. More often, however, storytelling repeated sacred stories about the Dreamings who created the world. These stories described the creation of the country and all the living things, including people.

The stars were commonly used to mark the seasons and to schedule food gathering activities. Aboriginal people of Australia recognized several constellations, including a great canoe called Julpan (known as Orion in Western societies) and the seven sisters (the Pleiades). According to Aboriginal myth, the seven sisters are pursued by a powerful warrior, seen among stars that rise behind them. One constellation, the “emu in the sky,” is identified by a dark patch of sky against the bright Milky Way between the constellations known as the Southern Cross and Scorpius. The dark patch represents the head of the great bird. Stories associated with the appearance of these constellations in the night sky served to mark time and remind people when to move to various regions where seasonal foods would be available.

Dance

was usually associated with Dreaming stories. The main musical instruments in North Australia were a didgeridoo (a pipe made of straight, hollowed-out pieces of wood) and clapsticks (two carved sticks struck rhythmically). Aboriginal musicians throughout Australia used clapsticks.

Singing

was an important part of Aboriginal life. Aboriginal peoples had women’s songs and men’s songs, secret songs and public songs. Some songs could only be sung during ceremonies. Others were for good luck in hunting, to make a child grow strong, to make rain, or to make someone fall in love. There were songs for sorrow and grief that were sung at funerals. Other songs were little poems that expressed the composer’s thoughts or feelings at a particular time. Individuals owned the songs they created, and songs could be traded.

Loading the player...Traditional Australian Aboriginal music

Trade.

Aboriginal trade routes covered the continent, connecting different social and ecological systems across Australia. Some of the routes probably existed for more than 20,000 years. Aboriginal people exchanged trade goods from person to person and from group to group. Scientists have documented this ancient trade by tracing the sources of particular types of stone used for tools. Some types of stone have been found up to 500 miles (800 kilometers) from their origin.

In addition to stone tools and blades, trade items included such objects as wooden and bamboo spears, different types of ocher, spear-throwers, sacred objects, and a chewing tobacco called pituri. Aboriginal people also exchanged songs and rituals called corroborees, and borrowed forms of social organization from other groups.

Through trade, it was possible for the people to use tools made of materials that they could not obtain locally. Trade also helped form partnerships outside of local groups. Partnerships were important, because if the food or water of one country failed, people needed to stay with neighbors who could support them temporarily. Especially in the desert, where rain was least predictable, people needed a good network of relations and partners on whom they could rely. In return for help in hard times, they would offer hospitality when their own country was having a good season.

Language.

When the first European colonizers arrived in 1788, there were about 250 Aboriginal languages, with about 600 dialects. Almost all of the Australian Aboriginal languages are clearly related to each other, but scholars are fairly certain that almost none of the languages are related to any other languages in the world. The language in the eastern Torres Strait Islands is related to Papua New Guinea’s languages. In contrast, the language of the western Torres Strait Islands is definitely Australian in origin. Recent work by Indigenous communities involves reclaiming and resurrecting traditional languages. In Tasmania, for example, there is also a renaming of locations, regions, and sites in the palawa kani language. The name palawa kani means Tasmanian Aboriginal people speak. The language is a composite Tasmanian Aboriginal language based on words from original Tasmanian languages resurrected from historical sources.

Aboriginal languages had a grammatical structure and a rich and complex vocabulary. In addition to everyday vocabularies, usually of about 10,000 words, many languages also included specialized words. Specialized language forms were used in songs and rituals, in jokes, and in conversation between special people.

Europeans used many Aboriginal words for the landforms, places, animals, and plants and helped spread their use throughout the continent. For example, the British explorer James Cook encountered the word kangaroo in what is now Queensland in 1770. The word then spread to all parts of Australia.

The arrival of Asians and Europeans

Asian visitors.

Ships from Asia reached Australia’s northern shores long before Europeans started exploring the area. In the 1400’s, visitors to Australia may have included Chinese, Arab, and Pacific Island explorers or traders. The most important of the early visitors came to Australia from the Indonesian port of Makassar (also spelled Macassar), from about 1700 until shortly after 1900 on fleets of fishing boats called praus. These Indonesian fishermen sailed to the northern coast of Australia to obtain trepang (sea cucumbers), tortoiseshell, mother-of-pearl, and other goods. Aboriginal peoples of the north traded with the visitors and gradually adopted some aspects of their culture. Dugout canoes, iron blades, and religious ceremonies are evidence of these contacts. Aboriginal song cycles and stories tell of this relationship, which ended by 1907, when the Australian government put an end to the trading.

In addition to Southeast Asians, some Japanese pearlers came to the waters off north Australia to look for pearls. Many Chinese gold miners came during the gold rushes of the mid-1800’s. Some of these Japanese and Chinese people stayed in Australia and married Aboriginal women.

First European explorers.

In 1768, the British Admiralty appointed the British navigator Lieutenant James Cook as captain of the Endeavor to find and take possession of what it called the southern continent. British authorities used this name for a large body of land they believed filled the entire southern part of the world. Cook landed at Botany Bay on the southeast coast of Australia on April 29, 1770, and continued northward, passing Port Jackson. On Aug. 22, 1770, he landed on what is now called Possession Island just off the coast of Cape York at the northern tip of Queensland. There, he claimed the east coast of the continent for Britain and named it New South Wales. Cook and his crew had found some areas on the east coast where they believed crops would grow and European farm animals could thrive. Cook did not understand the Aboriginal ways of land management. He assumed the Aboriginal people did not really own the country and it was therefore free for British settlement.

In the 1780’s, British government leaders wanted to establish a new colony. They could send prisoners from British jails there. Transportation (deportation to overseas colonies) was an important part of the British system of justice and punishment. Until the American Revolution (1775-1783), most British convicts were sent to the American Colonies, usually Maryland and Virginia. After the Revolutionary War began, the Americans would not accept any more British convicts. The British were also interested in Australia as a possible trading center.

Based on Cook’s descriptions and the urging of Sir Joseph Banks, who had served as botanist on Cook’s voyage, the British government agreed to establish a prison colony at Botany Bay. The First Fleet, under the command of Captain Arthur Phillip, left England with the first group of British convicts and their families on May 13, 1787. The fleet reached Botany Bay in January 1788 but found the location unsuitable. After a few days of unsuccessfully searching for water, Philip sailed farther north. He entered the large inlet of Port Jackson and there found Sydney Cove, with a fresh running stream and a protected harbor. On January 26, he raised the British flag there.

Challenges to traditional Aboriginal life

The arrival of the British settlers was a devastating turning point for the Aboriginal peoples. The Aboriginal population was greatly reduced by European diseases, violent conflicts with the settlers, dispossession (taking away of land), and the loss of traditional foods and resources. The British brought sheep and cattle that ate the vegetation, pounded the soils with hard hooves, and drank the water. The settlers used up the Aboriginal people’s food and water, and took control of the clans’ territories.

Aboriginal life was changed most dramatically in the south, southwest, and southeast—the regions that were intensively settled by the British. In areas that were too harsh for settlement, Aboriginal people remained relatively free, although the terrible effects of diseases spread even into the remote deserts.

The Europeans thought Australia’s Aboriginal inhabitants were uncivilized, primitive, and sometimes savage. Aboriginal people reportedly often greeted the newcomers with friendship but then discovered that their friendliness was misplaced.

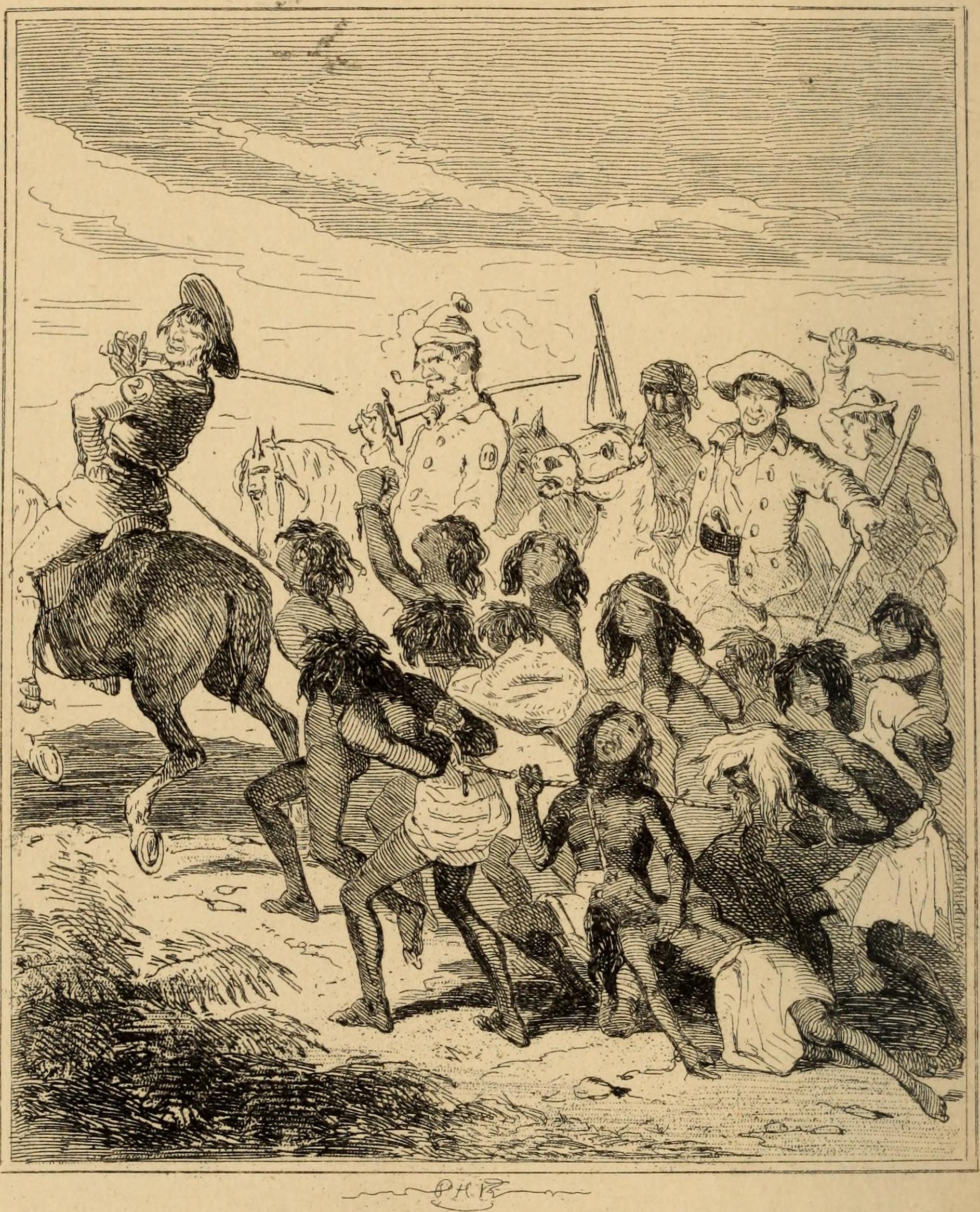

Violence.

Many settlers believed that the only way they could claim and occupy the land was to terrify the Aboriginal inhabitants with violence. Some colonizers opposed the violence, and some thought it was unfortunate but necessary. From the point of view of most Europeans, though, the issue was simple: They had come to Australia to make a life for themselves, and they would not be stopped. From the point of view of the Aboriginal peoples, the issue was equally simple: The country was theirs, and they would not give it up.

Many lives were lost in this conflict, most of them Aboriginal. Disputes erupted over many issues, including the settlers’ seizure of land and natural resources, and the relationships between Aboriginal clans and settlers. In some cases, Aboriginal people became angry when European men had relationships with Aboriginal women. In other cases, European men simply stole the women, killing the men and abandoning or kidnapping the children. Recent work documenting and recording the massacres across Australia has revealed that many more Aboriginal people died than was first thought.

The Myall Creek massacre near Inverell, New South Wales, in 1838, is one of the best known and best documented clashes between settlers and Aboriginal people. White cattle workers blamed a group of Aboriginal people for stealing and killing cattle. They killed about 28 Aboriginal men, women, and children. After a controversial trial, seven Europeans were hanged for the murders.

Other incidents of violence against Aboriginal groups and individuals were not well documented or were reported only through Aboriginal stories. Among the most recent documented massacres are the Forrest River massacre of 1926 and the Coniston massacre of 1928. In the Forrest River massacre, a group of police killed at least 11 Aboriginal people while searching for an Aboriginal man accused of murder. The Coniston massacre involved incidents of violence in which police and ranchers attacked Aboriginal people in retaliation for violence against a white rancher. The official death toll among the Aboriginal people was 31, but a later investigation found that as many as 60 to 100 were killed in the attacks.

Disease.

Europeans brought diseases that killed more Aboriginal people than conflicts did. Aboriginal people had no natural immunity (resistance) to such diseases as smallpox, influenza, measles, and whooping cough. In addition, sexually transmitted diseases had terrible long-term effects. Not only did they kill people, but they also made it impossible for afflicted adults to have children.

European control measures.

In the late 1800’s and early 1900’s, state governments passed laws with the stated goal of protecting Aboriginal individuals from abuses. Through this legislation, the government strictly controlled where and how Aboriginal people lived.

Land reserves.

The government set aside areas of land as reserves, saying that Aboriginal people could live there without fear of harm from settlers. Reserves did protect some people, but they did not provide the freedom that Aboriginal people needed. The practice of traditional religion and the speaking of Aboriginal languages were generally prohibited on reserves and missions. Forced to stay in one place, people no longer had access to their traditional foods and had to rely on food being brought to them. Their diet consisted mainly of flour, sugar, tea, and beef.

State officials also placed many Aboriginal people in government institutions or Christian missionary communities. The government provided little funding for these institutions, and in many places, the living conditions were harsh.

Forced labor.

The reserves, institutions, and missions provided workers for the European population. Aboriginal girls and young women went to work as servants. Boys and young men went to work as ranch hands or farm laborers. Many of them were subjected to cruel treatment and denied education. Adults were incorporated into the European ranching work force. In many parts of the Northern Territory, Queensland, and Western Australia, ranchers exploited Aboriginal labor. Managers of large ranches had almost absolute control over all Aboriginal workers and their families.

Many Aboriginal workers lived in extreme poverty. Laws allowed employers to pay them much lower wages than were paid to white Australians. The government denied them such benefits as pensions. Where Aboriginal people received wages, the money went to a government official called the protector of Aborigines rather than to the wage earners. The protector could choose to give it to the workers or withhold it from them. Many employers and protectors simply provided rations and accommodation, claiming they were putting wages into savings accounts. Since the late 1900’s, the stolen wages movement has become a significant and powerful reminder of these times. The movement seeks compensation for those who were denied their wages.

Protection boards

were government committees established to oversee Aboriginal education and employment. Government and missionary officials also used the protection boards to promote European behavior and dress. Officials discouraged traditional Aboriginal cultural practices. Even on reserves where there was no strong Christian influence, officials sought to suppress Aboriginal freedom of religion by banning major Aboriginal ceremonies.

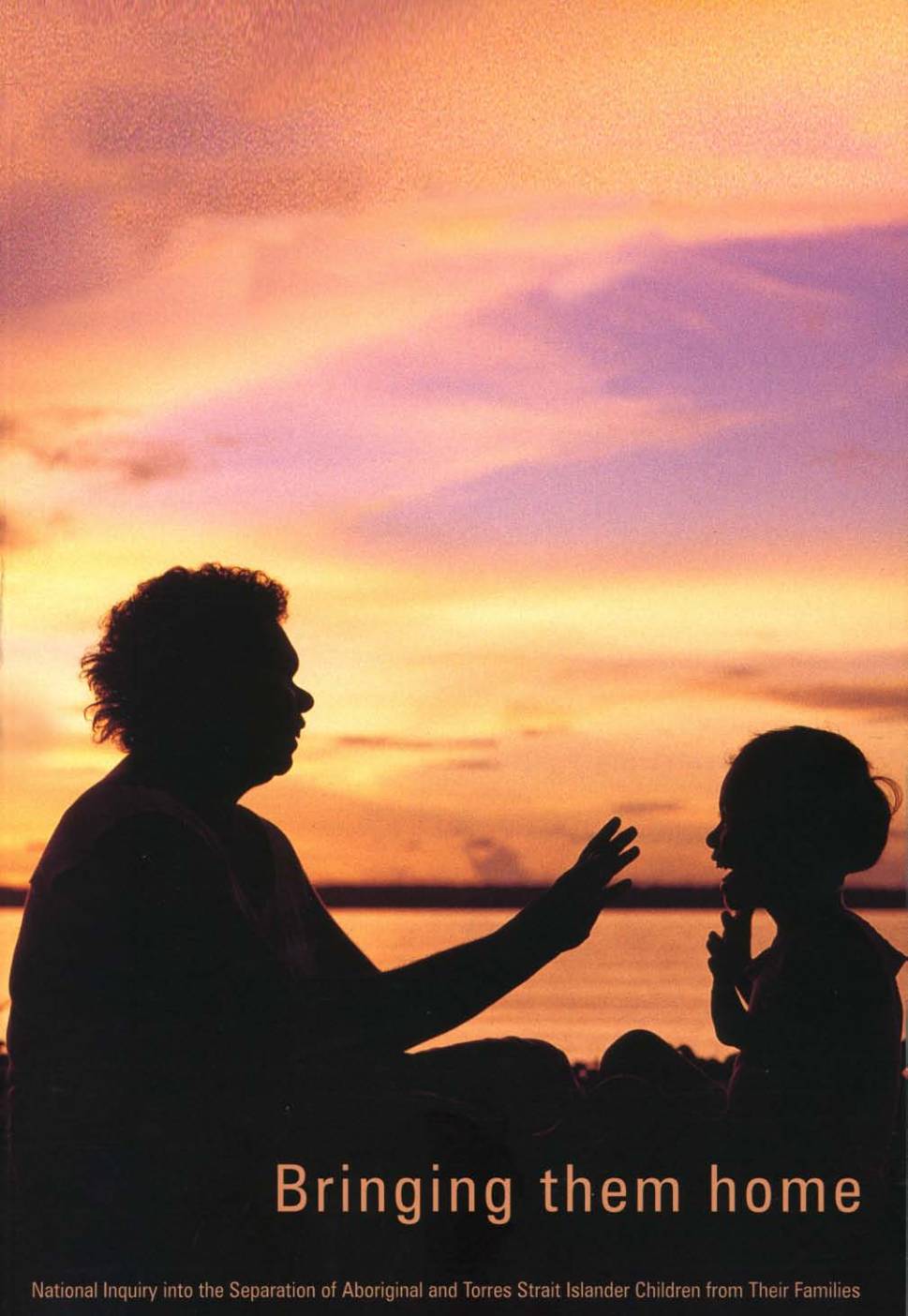

The Stolen Generations.

The government created the term socially developed for Aboriginal individuals who dressed and behaved like white Australians and did not frequently associate with other Aboriginal people. Government officials exempted (released) these individuals from the laws controlling and limiting Aboriginal rights. People with mixed Aboriginal and European parentage could also be exempted from the discriminatory laws.

Missionaries believed that they should raise children of Aboriginal descent, and particularly those of mixed Aboriginal and European descent, so that the children would assimilate into white society. To ensure this, the missionaries took children from their families and placed them in special government institutions, missions, or foster homes. The missionary leaders did not allow the Aboriginal children to speak their own language or to learn their Dreaming religion and laws. Government officials changed the children’s names and tried to prevent the children from finding their family and returning to their home country.

People who supported the policy of child removal claimed that the children were better off. However, conditions for the children were often harsh, and abuse was common. Opportunities for education were limited. Many Aboriginal children and families suffered considerable psychological damage. Aboriginal people’s distrust of government authority remains to this day. Many of the people who were removed have attempted to find their families and regain the cultural heritage they lost. Some have been successful.

Resistance and recognition

Aboriginal protests.

Since the early days of European colonization, Aboriginal people have launched formal protests over the loss of their land, the breakup of their family life, and the violent treatment they received. The Yorta Yorta people of Victoria have lodged numerous petitions and protests with the government from the 1880’s to the present day. In the 1920’s and 1930’s, Aboriginal people began to create political associations, particularly in southern and southeastern Australia. Such associations as the Australian Aborigines League (which later became part of what is now the Aboriginal Advancement League) and the Australian Aborigines Progressive Association called for an end to laws that discriminated against Aboriginal people. They protested the practice of child removal and publicized the poor conditions in which many Aboriginal families lived. Many non-Aboriginal groups involved in Aboriginal welfare joined the associations in calling for change. In 1938, on the 150th anniversary of the arrival of the First Fleet, Aboriginal activists organized a “Day of Mourning and Protest” to challenge discrimination and to call for land rights.

Aboriginal rights victories.

Malnutrition, disease, and hostile clashes with ranchers continued until well after World War II (1939-1945). After the war, international recognition of human rights increased. The Australian government signed international treaties on human rights and then had to consider its own policies toward Aboriginal people. Many people argued that Australia’s Indigenous peoples should be given the same rights, opportunities, and benefits as other Australians. Since that time, there have been numerous civil rights victories. In 1962, the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples received the right to vote in national elections. They received full social service benefits in 1966. In 1967, the Australian people passed a referendum (direct vote by the people) changing the Constitution to include the nation’s Indigenous peoples in the Australian census.

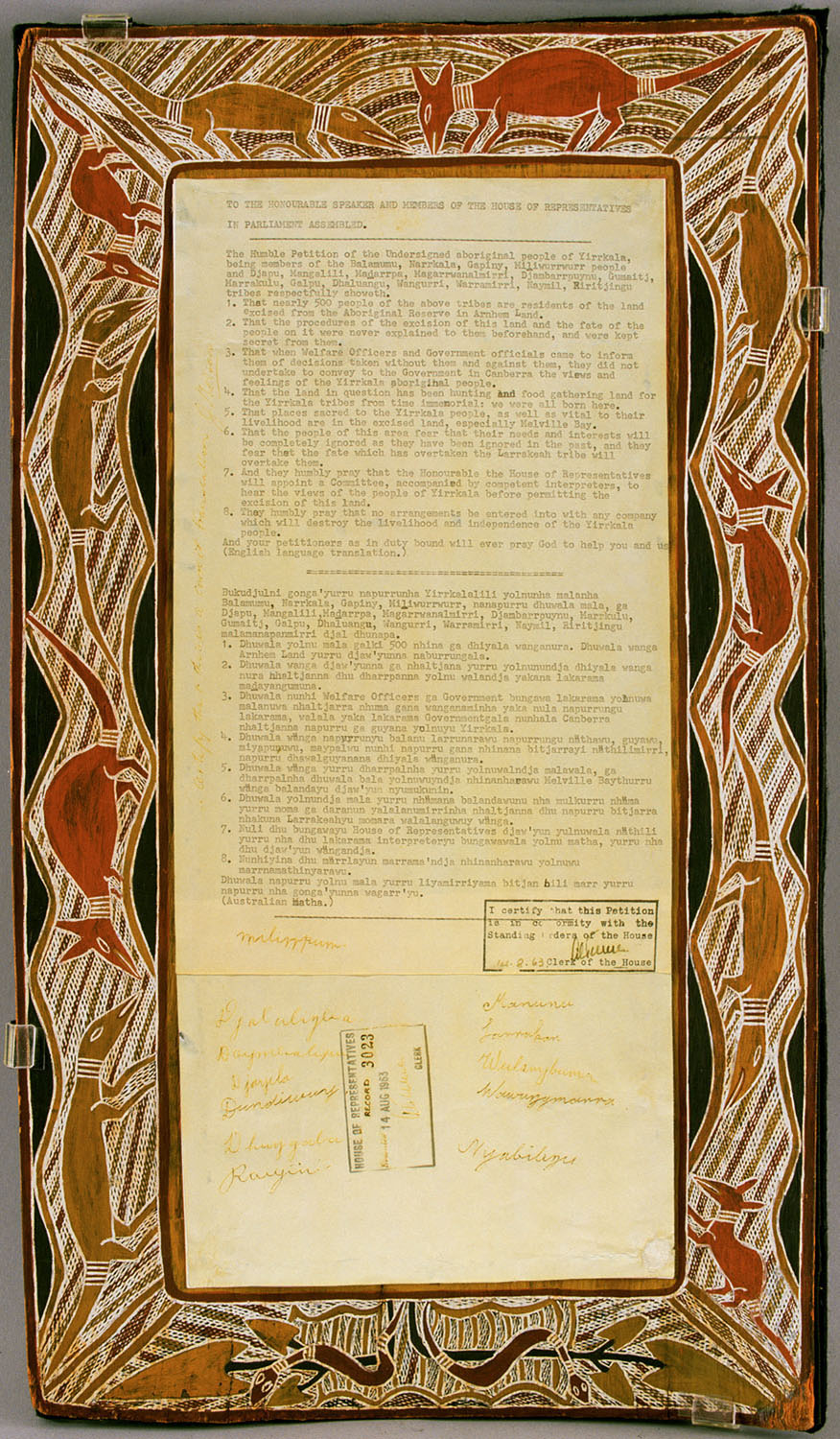

Aboriginal land rights

have been a large part of Aboriginal rights campaigns since the mid-1900’s. For much of Australia’s history, British and Australian law said that Australia was terra nullius, a Latin legal term meaning land belonging to nobody. In the 1960’s, several incidents brought the issue of land rights to the government’s attention. The Yolngu people of Yirrkala in the Northern Territory sought to have the government recognize their rights to land. Their petition was rejected. In 1966, Aboriginal workers on outback stations (ranches in the back country) in the Northern Territory held strikes to draw attention to their conditions. Their demands included better working conditions, equal pay for Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal workers, and the right to own land.

In 1973, the federal government appointed a commission to investigate the issue of land rights in the Northern Territory. The commission’s reports led to the passage of the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act in 1976. The act, which only applied to the Northern Territory, has led to the return of land to Aboriginal ownership. Almost 50 percent of the land in the Northern Territory is now owned and managed by Aboriginal people, including about 85 percent of the seacoast.

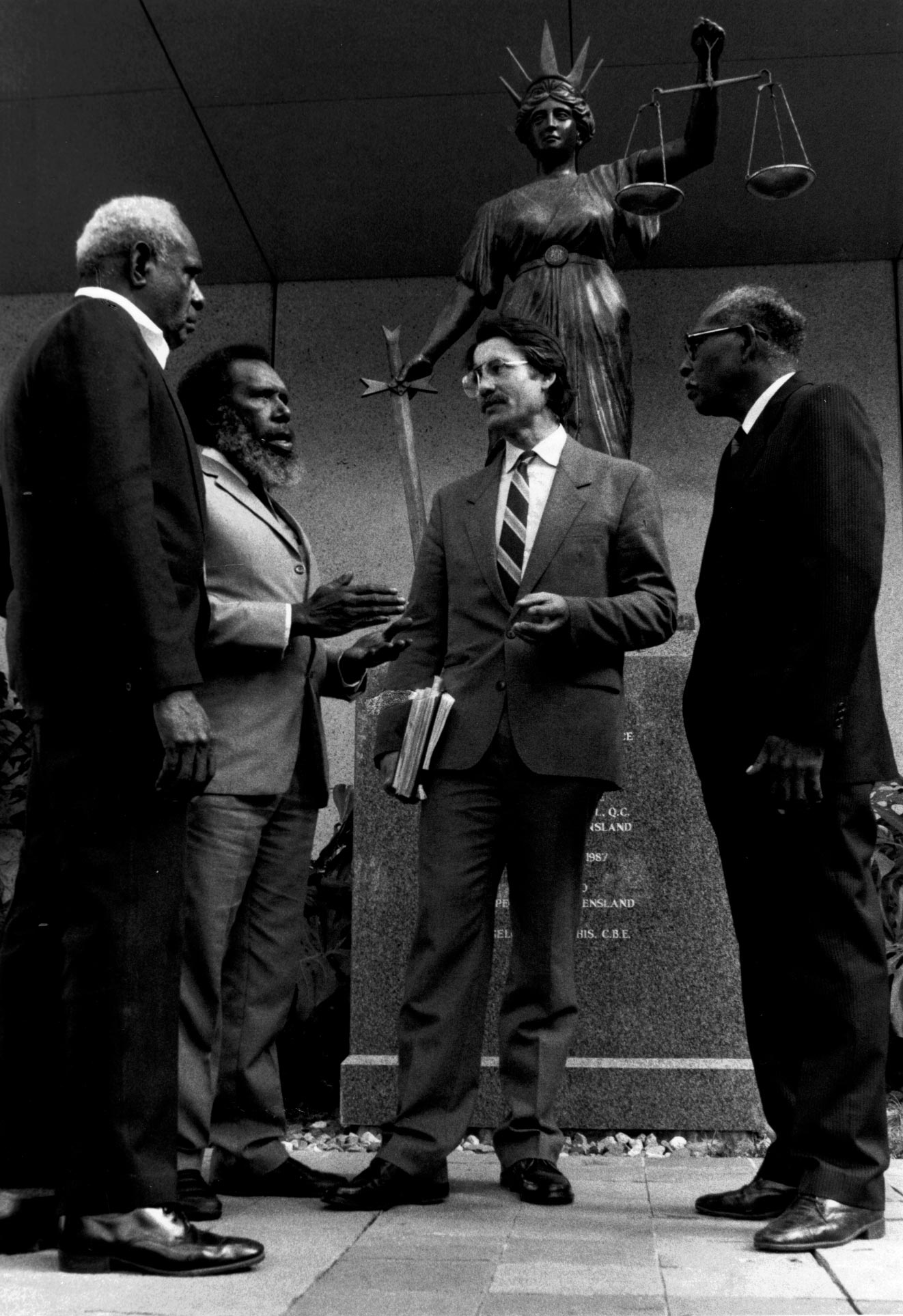

In the 1970’s and 1980’s, most states passed land rights legislation that included the return of former reserve lands to Aboriginal ownership. In 1995, the federal government passed legislation that established the Land Fund and Indigenous Land Corporation. This act enabled Aboriginal communities to purchase land and receive government assistance with land management.

The long struggle for Indigenous land rights won a significant victory in 1992 with the case of Mabo v. Queensland. Eddie Koiki Mabo and four other Torres Strait Islander people claimed that their people had lived on their land continuously since before the European invasion. The High Court of Australia determined that the claim was successfully demonstrated. It ruled that the theory of terra nullius was not correct and was illegal. In this landmark case, the court recognized that native title had existed at the time of the invasion and still existed where Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples continued to occupy their land. According to the ruling, Australia’s Indigenous peoples had complex systems of land possession before British settlement. The court called this form of ownership native title.

Since the Mabo decision, Aboriginal peoples have filed more court cases for land claims. The Wik Aboriginal community claimed native title over an area of leased pastoral (grazing) land in north Queensland. In 1996, the High Court ruled in the Wik decision that leasees and Aboriginal people could both have rights on the same land. When pastoralists and native titleholders come into conflict, the court said that the native title rights would be voided.

In 1998, the Australian Parliament passed the Native Title Amendment Act, which substantially reduced the land rights granted under the Native Title Act. Passage of the Native Title Amendment Act followed the longest debate in the Parliament’s history. Aboriginal leaders denounced the act as a major reduction in Aboriginal land rights and vowed to challenge it in court.

Aboriginal peoples today

Continued difficulties.

Australia’s Aboriginal peoples have made great gains in the areas of civil and land rights and in overcoming discrimination. Aboriginal languages, art, religion, ritual, and other aspects of their traditional life are gaining increasing acceptance and support within Australia and abroad. Despite these gains, however, the Aboriginal peoples of Australia still face many difficulties. They are underprivileged economically, socially, and politically. They face more problems than white Australians face in such areas as health, education, and employment.

Aboriginal deaths in police custody.

Since the late 1980’s, a high number of deaths of Aboriginal persons while in police or prison custody has caused concern within Australia. Government officials held an inquiry on the issue from 1987 to 1991. The inquiry found that Aboriginal individuals were more likely to be arrested and jailed than non-Aboriginal individuals. The inquiry established that those people who had been removed from their families, the Stolen Generations, were vastly more likely to be caught up in the judicial system. The report made recommendations to all levels of the Australian government to address the disadvantages and discrimination Aboriginal people face. In response, governments across Australia increased spending on Aboriginal health, education, employment, housing, and community programs. There are more programs now to improve police relations with Aboriginal people and to overcome the racism that exists among some Australians. However, most of the recommendations have not been acted upon in the years since the report was issued.

An important result of the inquiry was the establishment of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (ATSIC) by federal legislation in 1989. ATSIC was an elected Aboriginal body that represented Aboriginal interests and administered a large part of the money given to Aboriginal programs. In 2004 and 2005, the Australian government abolished ATSIC and its associated agency, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Services (ATSIS). The programs and services of ATSIC and ATSIS were transferred to other government agencies.

Health problems.

The health of Aboriginal people is poorer than the health of other Australians. Aboriginal people have a life expectancy that is 15 to 20 years shorter than the rest of the Australian population. The number of Aboriginal babies who die before reaching their first birthday is two to five times higher than the national average.

Introduced diseases have less impact now than they had in previous centuries. However, Aboriginal people are still likely to develop complications from common infectious diseases. Malnutrition persists, as well as a higher risk for such conditions as heart disease, kidney failure, diabetes, and strokes. Poor housing, sanitation, and hygiene are also significant community issues. A movement to address this inequity began in the early 2000’s. Since 2009, the prime minister of Australia has been bound to present the annual Closing the Gap report in the federal Parliament to track progress in these areas.

Alcohol abuse

and other forms of substance abuse are also significant issues in Aboriginal communities. Alcohol abuse contributes to domestic violence, crime, and unemployment, as well as health problems. Aboriginal communities are developing awareness and treatment programs. Many community leaders and government officials believe improving Aboriginal health, education, and employment levels would reduce abuse problems.

Unemployment

levels among the Aboriginal population are higher than for Australians as a whole. Educational achievement is lower among Aboriginal peoples than among other groups in Australian society. As a result, many Aboriginal men and women can only compete for unskilled, low-paying jobs.

Reconciliation.

In 1997, the Human Rights and Equal Opportunities Commission, an Australian government agency, released a report about the Stolen Generations. The report was highly critical of child removal policies. The commission said that these policies were acts of genocide (extermination of an entire people). Following the publication of the report, Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal groups called for Prime Minister John Howard to make a public apology on behalf of the Commonwealth government for past policies. The prime minister expressed regret but declined to make an official apology.

Since the early 1990’s, there has been an official process for settling disagreements between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people and for bringing the two peoples together in friendship. This process, called reconciliation, was formalized by an act of Parliament that established the Council for Aboriginal Reconciliation in 1991. At the Corroboree 2000 reconciliation conference in Sydney, more than 200,000 people joined together in a walk across the Sydney Harbour Bridge to show support for the reconciliation process. Similar walks in other cities have attracted large numbers of people, and groups have organized opportunities for apologies. In 2001, Reconciliation Australia replaced the Council for Aboriginal Reconciliation.

In the first sitting of the federal Parliament in 2008, the prime minister of Australia, Kevin Rudd, made an official apology to the Indigenous peoples of Australia on behalf of the commonwealth government. The apology formally acknowledged past wrongs as well as laws and policies that inflicted grief, suffering, and loss among the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

Loading the player...Kevin Rudd delivers apology to Indigenous Australians

First Nations Voice.

In 2015, Prime Minister Malcolm Turnball established the Referendum Council, a group made up of Indigenous leaders, legal scholars, and other experts. In 2017, after holding discussions with Indigenous communities, the council called for a constitutional amendment to address the legal and political concerns of Indigenous peoples. In 2023, the government of Prime Minister Anthony Albanese held a nonbinding referendum on a constitutional amendment to establish the First Nations Voice. This proposed advisory group would represent the interests of the country’s Indigenous peoples, also called First Nations peoples, in Parliament. It would consist of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. In the referendum, a majority of voters rejected the amendment, despite strong support for it among Indigenous people.

International success

of Aboriginal art has increased since the late 1900’s. The production of paintings and wooden artifacts, such as boomerangs and didgeridoos, provides valuable income to many Aboriginal communities. Leading Aboriginal artists have displayed their work in major exhibitions in Australia and overseas. Aboriginal art on canvas, bark, paper, and other surfaces, using modern acrylic paint or ocher, is highly prized throughout the world today. Some of the best Aboriginal artists have exhibited their work in the major art centers of the world.

Aboriginal dance and music are growing in popularity as well. Aboriginal dance groups perform at official functions, cultural events, and events organized for groups of tourists. The Aboriginal dance group Bangarra has toured throughout Australia and in Japan, Europe, and the United States. The musical group Yothu Yindi achieved international success through blending aspects of traditional music and Western popular music styles. The late singer and song writer Geoffrey Gurrumul Yunupingu transcended genres and collaborated with Indigenous and non-Indigenous artists. Internationally successful filmmakers include Rachel Perkins, Ivan Sen, and Warwick Thornton.

Inspirational achievers.

Australia’s Aboriginal community today offers many examples of successful and inspiring individuals. Some of Australia’s leading athletes are of Aboriginal descent. They have excelled in sports as diverse as hockey, rugby, tennis, and track and field. During the 1970’s, the Aboriginal tennis player Evonne Goolagong Cawley won four Australian Open singles titles, as well as two Wimbledon Championships and one French Open title. Mark Ella captained the Australian Rugby Union team in the 1980’s. The Aboriginal track star Cathy Freeman gained international recognition after she was chosen to light the flame at the opening ceremonies of the 2000 Summer Olympic Games in Sydney. In 2020, the internationally top-ranked tennis player Ash Barty was named Young Australian of the Year.

Notable Aboriginal musicians have included the singer-songwriters Jimmy Little and Archie Roach; and the singer and guitarist Mandawuy Yunupingu, who led Yothu Yindi.

Distinguished Aboriginal activists and scholars include the legal scholar and novelist Larissa Behrendt; the civil rights activist Pearl Gibbs; the award-winning author Anita Heiss; and Terri Janke, an expert on Indigenous rights and intellectual property. They also include Marcia Langton, an activist, anthropologist, and author; Sally Morgan, an artist and author; Noel Pearson, an activist and lawyer; and Shirley Smith, an activist and social worker.