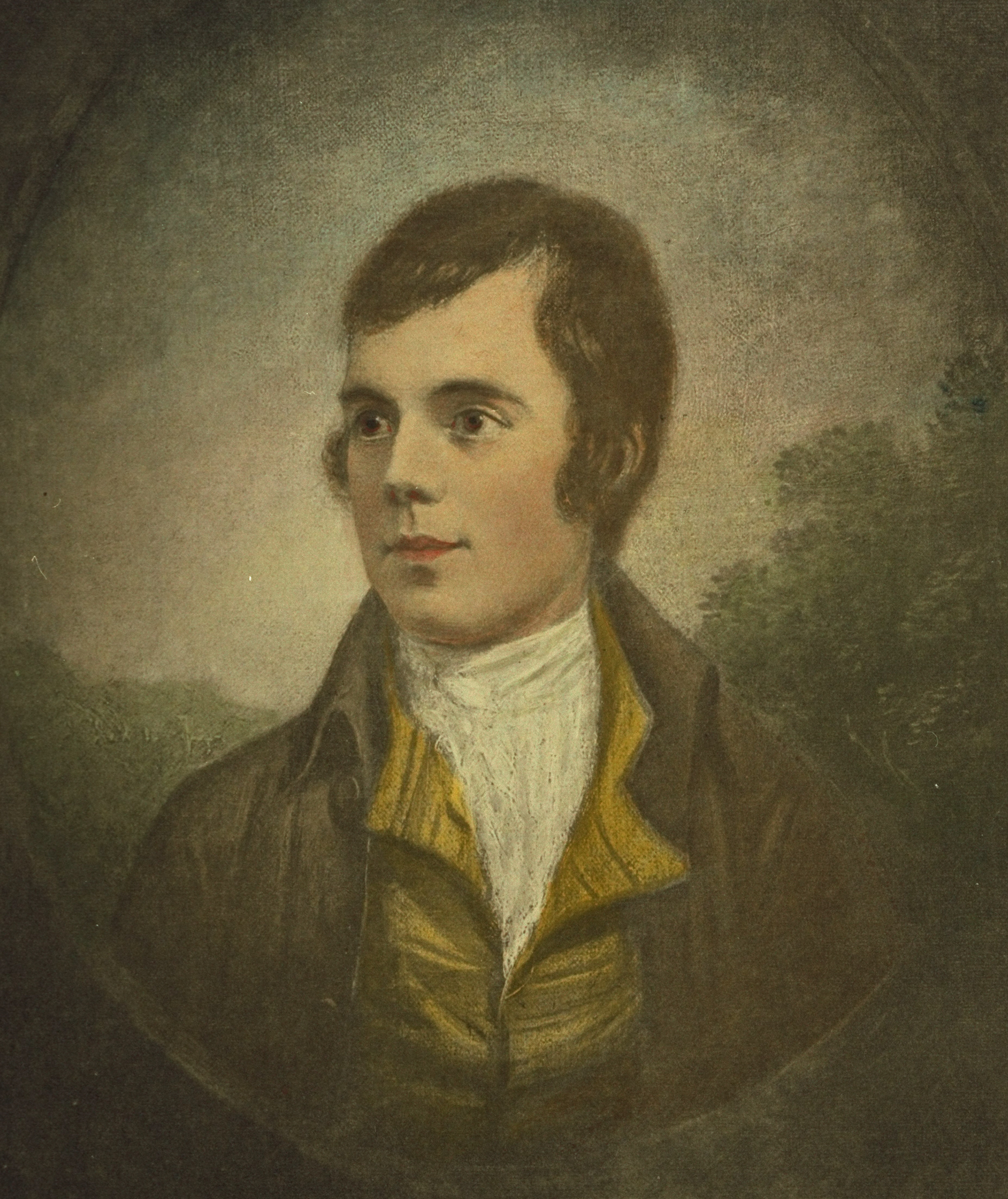

Burns, Robert (1759-1796), is the national poet of Scotland. He wrote brilliant narrative poems, such as “Tam o’ Shanter,” and clever satires, including “The Holy Fair,” “Address to the Deil,” and “Holy Willie’s Prayer.” However, Burns is probably best known for his songs, especially “Auld Lang Syne,” “Comin Thro’ the Rye,” and “For a’that and a’that.” Many of Burns’s lines have become familiar quotations. These lines include “Oh wad some Pow’r the giftie gie us/To see oursels as others see us!” from “To a Louse”; and “The best laid schemes o’ mice and men/Gang aft agley” from “To a Mouse.” See Auld Lang Syne .

Burns’s life.

Burns was born on Jan. 25, 1759, in Alloway, a village on the River Doon. Like his father, Burns was a farmer, and he remained one almost all his life, despite his success as a writer. The farmer’s hard way of life taught Burns to take joy in fleeting pleasure and to be skeptical of the moral codes of the well-to-do. These attitudes, along with his capacity for love, friendship, and hearty tavern fellowship, provide the chief themes of his poetry. Burns had only a few years of formal education, but he read many books by English and Scottish authors. In his traditional “verse epistles,” or “letters” from one poet to another, Burns summarized the simple rustic focus of his work: “Give me a spark o’ Nature’s fire!/That’s a’ the learning I desire.”

In 1786, Burns decided to move to Jamaica because of setbacks in farming and an unhappy love affair with Jean Armour, a Scottish girl. But the success that year of his first volume of poems caused him to change his mind. He went, instead, to Edinburgh, where, for over a year, he was popular with fashionable society.

In 1788, Burns returned to farming. That year, he married Armour. They had nine children. Burns’s literary success helped him get an appointment as exciseman (tax and customs official) in 1788. This position gave Burns a steady income for the rest of his life. In 1791, he gave up farming and moved to Dumfries. He died there on July 21, 1796, at the age of 37. The heavy farm labor in Burns’s youth had weakened his health and helped cause his early death.

Burns’s works.

Burns was interested in authentic folk songs. He collected about 300 original and traditional Scottish songs for books compiled in his day, including The Scots Musical Museum (1787). Burns wrote many poems to be sung to Scottish folk tunes. He adapted some of his best-loved songs, including “Comin Thro’ the Rye,” from bawdy lyrics. Others, such as “A Red, Red Rose,” he pieced together almost entirely from songs by other writers. But even those works that Burns adapted from other sources have qualities uniquely his own.

Loading the player...Auld Lang Syne

Burns wrote in both the Scots dialect and standard English. He wrote in English when he wanted to express customary or respectable ideas, as in “A Prayer in the Prospect of Death” and much of “To a Mountain Daisy.” When Burns wished to express ideas that conflicted with custom or that dealt with less respectable aspects of human nature, he adopted the language of the uneducated Scottish peasant. Examples include “The Jolly Beggars” and “Address to the Unco Guid.”

In his time, Burns was considered an unlearned plowman, but he was really a skilled poet. He could use not only a traditional Scottish stanza form, as in “To a Mouse,” but also the sophisticated English Spenserian stanza, as in “The Cotter’s Saturday Night.” The dialect Burns used was a partly artificial language adapted from earlier Scottish writers, including Allan Ramsay and Robert Fergusson. Sometimes, Burns did not use true dialect, but respelled English words and phrases in Scots. He used much more art than people thought, but what we feel is not so much the art as the vigorous life of his poetry.

See also Red, Red Rose, A .