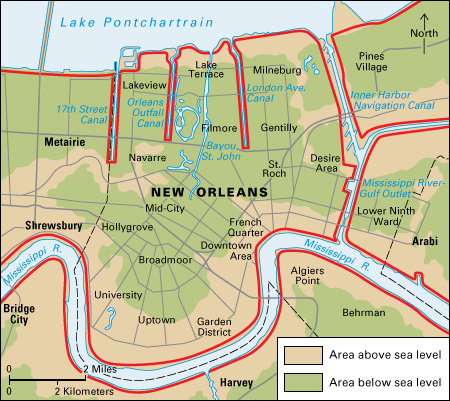

Hurricane Katrina was one of the most destructive storms ever to strike the United States. In late August 2005, the hurricane formed as a tropical storm in the Caribbean Sea and struck the southern tip of Florida. It then gained strength in the Gulf of Mexico and made landfall near the Louisiana-Mississippi border on Aug. 29, 2005. The hurricane brought high winds, huge waves, and flooding that caused much damage in Florida and widespread destruction in parts of Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama. The storm killed about 1,800 people, caused about $100 billion in damage, and left hundreds of thousands of people homeless. New Orleans, much of which lies below sea level and quickly flooded, suffered some of the worst damage and loss of life. About 80 percent of the city was flooded, and of the approximately 1,500 Louisianians who died because of the storm, most were from New Orleans.

Many people responded to the disaster by donating their money and time, and governments set aside billions of dollars toward relief and rebuilding efforts. However, in the weeks and months after the storm, critics questioned the preparedness for, and response to, the disaster by governments at the national, state, and local levels.

The storm.

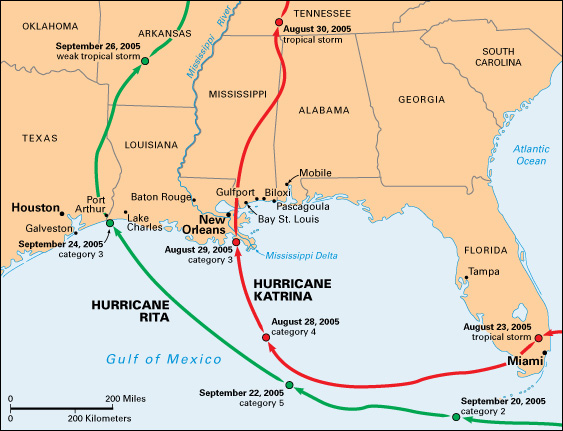

The hurricane started as a tropical depression near the Bahamas in the Caribbean Sea on August 23. A tropical depression is a low-pressure area surrounded by winds that have begun to blow in a circular pattern. The storm strengthened and moved west. On August 25, its winds reached hurricane intensity of 75 miles (120 kilometers) per hour and struck the southern tip of Florida. The area suffered much damage and several deaths. The storm crossed Florida and continued westward into the Gulf of Mexico, where it grew stronger. By August 28, the hurricane had started to move northwest in the direction of New Orleans.

On the morning of August 29, Hurricane Katrina struck the Gulf Coast. Wind gusts of more than 125 miles (200 kilometers) per hour, coupled with storm surges (rapid rises in sea level produced when winds drive ocean waters ashore) reaching up to 34 feet (10.4 meters), devastated several coastal communities. These communities included Bay St. Louis, Biloxi, Gulfport, Pascagoula, and Pass Christian in Mississippi; and Bayou La Batre, Dauphin Island, and Mobile in Alabama. The storm surges destroyed numerous homes, businesses, and roads and bridges. In New Orleans, winds of up to 100 miles (160 kilometers) per hour damaged many buildings. But rapidly increasing water levels brought the most destruction. A storm surge pushed water over and through several parts of the New Orleans system of levees (flood barriers). The city’s low-lying neighborhoods quickly became submerged.

The aftermath.

In the days after the storm, newspaper, television, and Internet reports showed images of many New Orleans residents stranded on rooftops amid the flooded streets. Thousands took shelter in and around the city’s convention center and sports stadium, where conditions rapidly deteriorated. Many waited for several days for buses to transport them to shelters in other cities. The sick and elderly in a number of hospitals and nursing homes were left without water, electric power, and ventilation, and many died. Rescue teams worked day and night throughout the city but lacked the resources to deal effectively with the large number of people in need of help.

Government officials and private citizens responded to the storm’s aftermath in many ways. President George W. Bush signed two bills contributing more than $60 billion to disaster relief. Many communities opened shelters to people displaced by the storm. Individuals and private groups from around the world donated billions of dollars to charities assisting in the recovery. Many volunteers, including medical personnel and animal rescuers, came to the Gulf Coast from across the United States to offer their help.

Criticism.

On September 1, Michael Brown, director of the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), revealed to a television reporter that until then, he had been unaware that thousands of people were stranded at the New Orleans Convention Center. His statement, together with President Bush’s comment praising Brown’s work during the disaster, helped direct media attention to an examination of the effectiveness of the federal relief effort. Brown later resigned amid criticism about his performance and qualifications. Louisiana Governor Kathleen Blanco and President Bush disagreed over who would control National Guard troops sent into the troubled city. People criticized the government for what they saw as a failure to heed warnings of what a hurricane could do to New Orleans, and for failing to take steps to repair an aging levee system.

The investigation.

On Sept. 15, 2005, the U.S. House of Representatives set up a panel to investigate the government’s Hurricane Katrina response. The House released the panel’s findings in a February 2006 report entitled “A Failure of Initiative.” The report found fault with government at all levels for failing to prepare for such a hurricane, saying one had been predicted in theory for years, and that Katrina’s landfall was accurately forecast five days in advance.

The report placed much of the blame on a lack of leadership by federal officials, including Michael Chertoff, the head of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, which oversees FEMA. The report said that a lack of communication and cooperation among federal agencies, the White House, the military and other rescue personnel, and state and local authorities led to significant delays in identifying major problems and providing relief to those in need. Although the report generally praised state evacuation efforts, it criticized Governor Blanco and New Orleans Mayor Ray Nagin for waiting too long before ordering a mandatory evacuation of New Orleans.

The House report praised the heroic efforts of some individuals and commended the National Weather Service and National Hurricane Center, whose forecasts prevented greater damage and loss of life. The report expressed the need for strong leadership and the sharing of information to prevent similarly ineffective responses to future disasters.

Moving forward.

In the years following the storm, residents of the Gulf Coast began rebuilding communities affected by Hurricane Katrina. Many evacuees, lacking homes and jobs to return to, settled permanently outside of the region. In New Orleans, an upgraded levee system was completed in 2013. Many people, however, questioned the wisdom and cost of redeveloping the city’s depopulated low-lying neighborhoods. Having faced heated criticism, governments at all levels felt pressure to demonstrate that they could respond effectively to disasters in the years to come.