Butterfly is among the most beautiful of all insects. The four delicate wings of a butterfly appear in nearly every color imaginable. The colors may be bright, pale, or shimmering and often form stunning patterns. The word butterfly comes from the Old English word buterfleoge, meaning butter and flying creature. The “butter” probably comes from the butter-yellow color of some European butterflies. The beauty and grace of butterflies have inspired painters and poets. Butterflies also appear in folklore and mythology. The ancient Greeks, for example, believed that the soul left the body after death in the form of a butterfly. They sometimes imagined the soul as a butterfly-winged girl named Psyche.

The largest butterfly, Queen Alexandra’s birdwing of Papua New Guinea, has a wingspread of about 11 inches (28 centimeters). One of the smallest butterflies is the western pygmy blue of North America. It has a wingspread of about 3/8 inch (1 centimeter).

Butterflies live almost everywhere in the world. Tropical rain forests have the greatest variety of butterflies. Other butterflies live in woodlands, fields, and prairies. Some butterflies live on cold mountaintops, and others live in hot deserts. Many butterflies travel great distances to spend the winter in warm climates.

People are still finding new species (kinds) of butterflies. Scientists think that there may be about 20,000 to 30,000 species in total.

Butterflies and moths together make up an insect group called Lepidoptera. The name comes from two Greek words meaning scale and wing. It refers to the powdery scales that cover the wings of both butterflies and moths. However, butterflies differ from moths in a number of important ways, including the following four. (1) Most butterflies fly during the day. The majority of moths, on the other hand, fly at dusk or at night. (2) Most butterflies have knobs at the ends of their antennae. The antennae of most moths are not knobbed. (3) Most butterflies have slender bodies. The majority of moths are plump. (4) Most butterflies rest with their wings held upright over their bodies. Most moths rest with their wings spread out flat. These differences, however, have many exceptions.

A butterfly begins its life as a tiny egg. The egg hatches into a caterpillar. The caterpillar spends most of its time eating and growing. The caterpillar’s skin cannot grow, so the caterpillar must shed its skin to get larger. This process repeats several times. After the caterpillar reaches full size, it forms a protective covering. Inside this shell, an amazing change occurs—the wormlike caterpillar becomes a beautiful butterfly. The shell then breaks open, and the adult butterfly comes out. The insect spreads its wings and soon flies off to find a mate. Together, they produce a new generation of eggs.

Butterflies mainly feed on plants. Their caterpillars chew up leaves or other plant parts. Some kinds of caterpillars are pests because they damage crops. Adult butterflies, on the other hand, feed mainly on nectar and do no harm. In fact, they may help plants by carrying pollen from blossom to blossom. When a butterfly stops at a flower to drink nectar, pollen may cling to the butterfly’s body. Some of the pollen may then rub off on the next blossom the butterfly visits. This transfer of pollen, called pollination, helps the plant to produce fruit and seeds. Pollination is one of many reasons that people work to protect butterflies.

Kinds of butterflies

Scientists group the thousands of species of butterflies into different families. The chief families include (1) skippers; (2) blues, coppers, and hairstreaks; (3) metalmarks; (4) brush-footed butterflies; (5) satyrs and wood nymphs; (6) milkweed butterflies; (7) snout butterflies; (8) sulphurs and whites; and (9) swallowtails. Scientists established these groups more than a century ago, based on similarities and differences in the butterflies’ bodies. Some scientists have argued that certain families should be combined, but not all butterfly experts agree.

In addition, a little known family of night-flying insects once considered moths may actually be butterflies. These insects, from the American tropics, have been called “moth butterflies.”

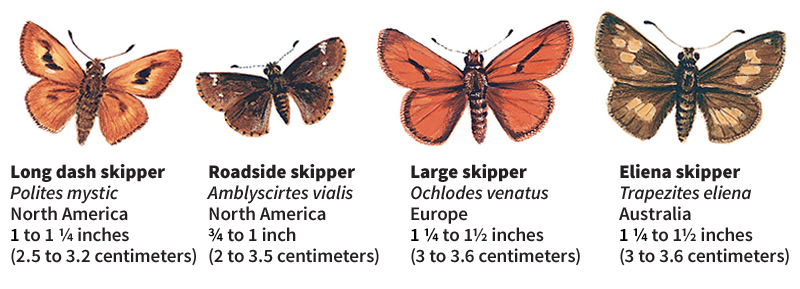

Skippers

differ from all other kinds of butterflies in two major ways: (1) Skippers have plump bodies and therefore look more like moths; and (2) their antennae have hooked tips, unlike the rounded tips on the antennae of other butterflies. For this reason, scientists classify skippers separately from true butterflies.

Skippers live in all parts of the world, except for the extreme polar regions. Skippers get their name from the way they swiftly skip and dart while flying. They range in color from orangish-brown to dark brown. In many cases, they have white and yellow markings. The brightest and showiest skippers live in the tropics, as is common among butterflies. North American skippers include the silver-spotted skipper, the roadside skipper, the fiery skipper, the checkered skipper, Juvenal’s duskywing, and the least skipperling.

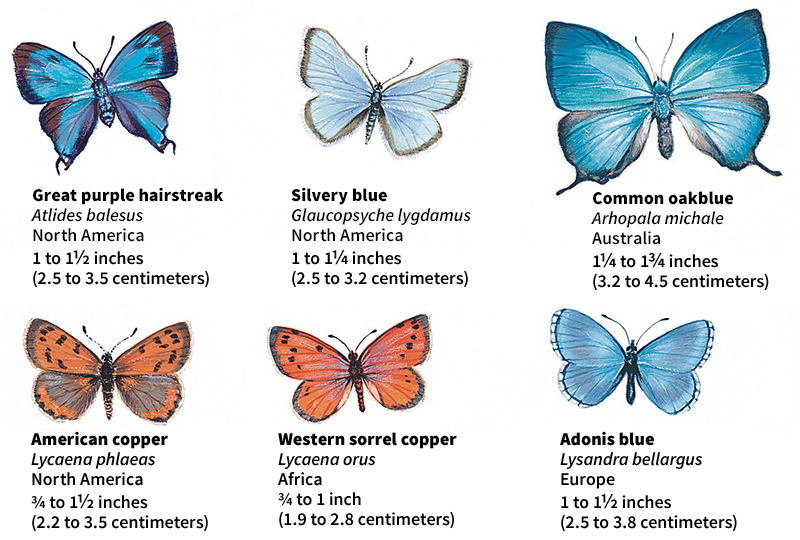

Blues, coppers, and hairstreaks

live in almost every type of environment. They are small butterflies whose names describe their appearance. Blues have a brilliant blue or violet color. Coppers are often a fiery orange-red. Most species of hairstreaks have a hairlike “tail” on each of their hind wings. A number of blues and coppers also have such “tails.”

Members of this family include the spring azure, the bronze copper, and the great purple hairstreak. The caterpillars of some species produce a sweet liquid known as honeydew. Certain ants “milk” the honeydew from the caterpillars. They also protect the caterpillars from being eaten. The large blue, a striking butterfly, disappeared from the United Kingdom in 1979. It has since been reintroduced and is recovering. Blues, coppers, and hairstreaks make up a large share of endangered butterflies.

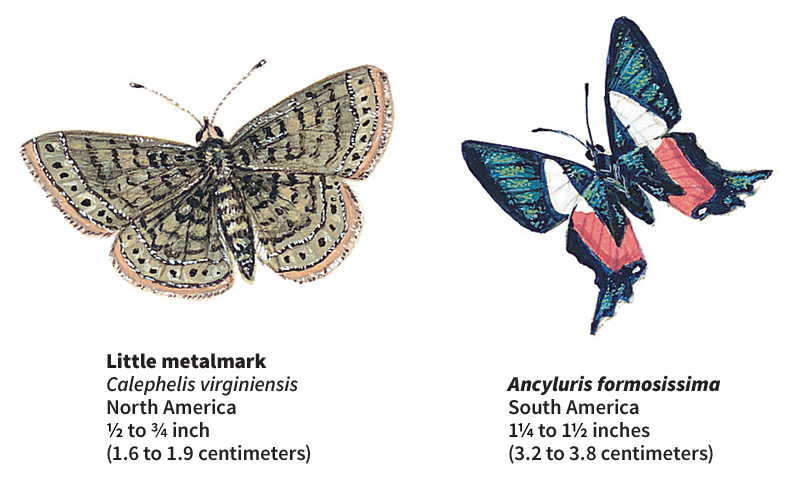

Metalmarks

live around the world but are especially numerous in South America. Some scientists consider them a subfamily of the blues, coppers, and hairstreaks. Their name comes from metallic-looking marks on the wings of some species. Tropical metalmarks may have almost any combination of colors and patterns. Among the most colorful is a Peruvian species known by the scientific name Ancyluris formosissima.

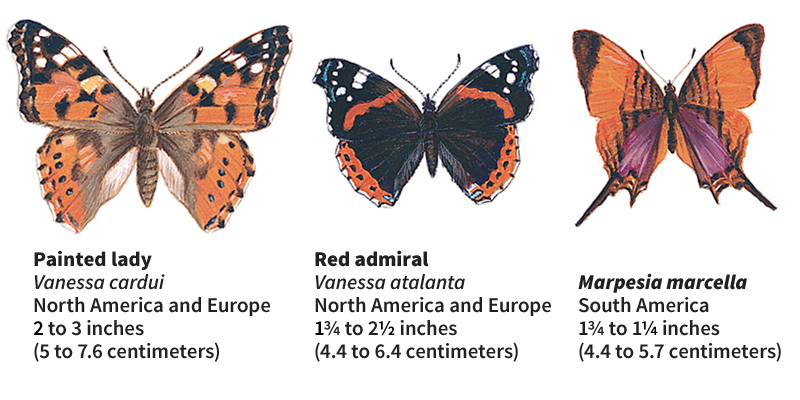

Brush-footed butterflies

or brushfoots live everywhere in the world, except for ice-covered polar regions and deserts. These butterflies have short front legs, called brush feet. Special organs on the brush feet help the insects find food. The brush feet are not used for walking. Most brushfoots have wings with bright upper surfaces and dark lower surfaces. When the butterfly closes its wings, the dark color of their undersides helps the insect blend with its surroundings.

Brush-footed butterflies include the small crescents and checkerspots and the large fritillaries. Some of the best-known butterflies—the viceroy, the red admiral, and the mourning cloak—are brushfoots.

Satyrs and wood nymphs

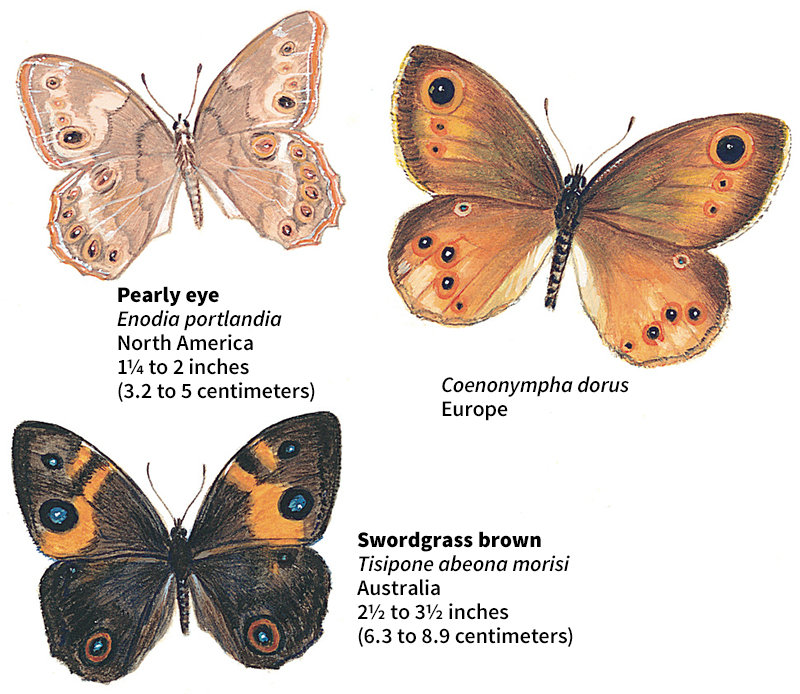

are often considered a subfamily of the brushfoots. Most kinds live in the tropics. However, a few live in high mountainous regions and the Arctic. New Zealand has several unusual satyrs, including the colorful tussock butterfly. The caterpillars feed on grasses and related plants, including bamboo. Satyrs and wood nymphs have short front legs and fly close to the ground. Most have brown wings dotted with eyespots (markings that resemble eyes).

Milkweed butterflies

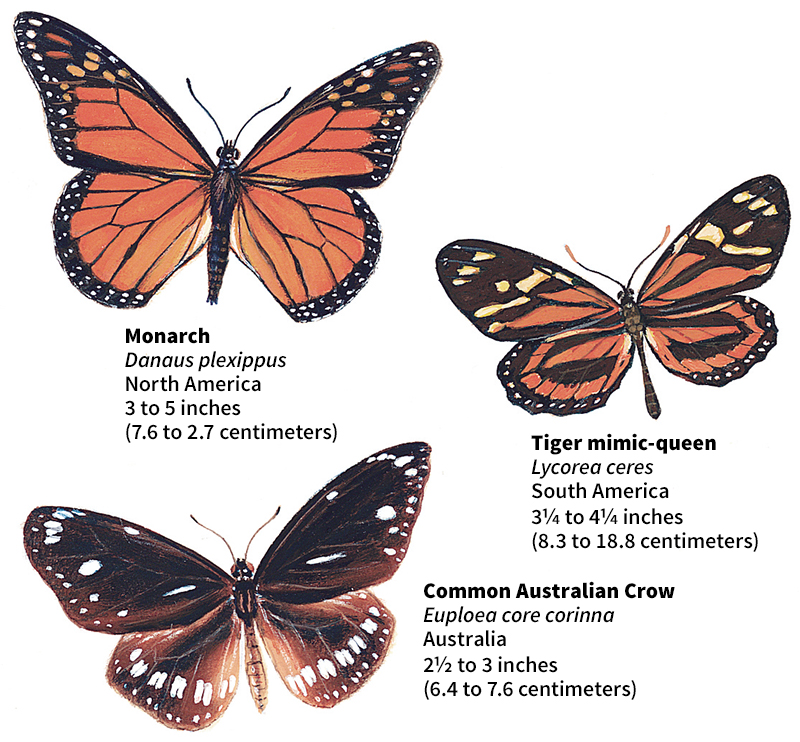

are large, slow-flying butterflies with short front legs. Their caterpillars feed on milkweed plants. Milkweed butterfly wings range from orange to brown, with black veins and margins. Many of them have white spots. Some African and Asian species are blue, violet, or white, with brown markings. Many scientists group milkweed butterflies with brushfoots.

One milkweed butterfly, the monarch, is famous for its long flights south each fall. The common crow butterfly of Australia and India also migrates long distances.

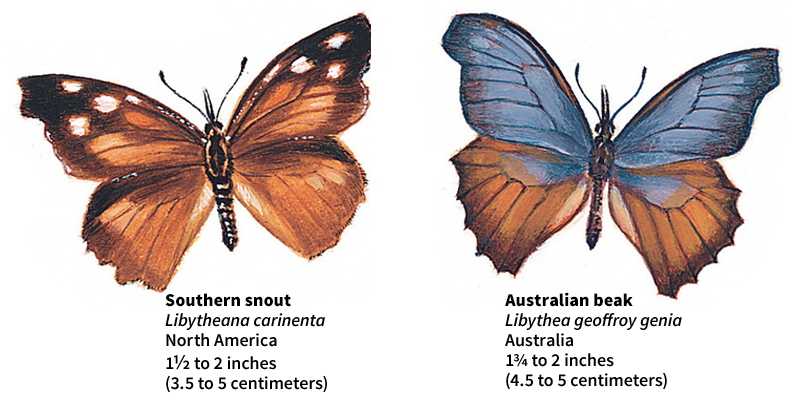

Snout butterflies

live mostly in the tropics. These butterflies get their name from their long, beaklike mouthparts. The Australian beak ranks among the more colorful snout butterflies. The snout butterflies are an ancient family, known to appear in 70-million-year-old fossils. Some experts group them with the brushfoots.

Sulphurs and whites

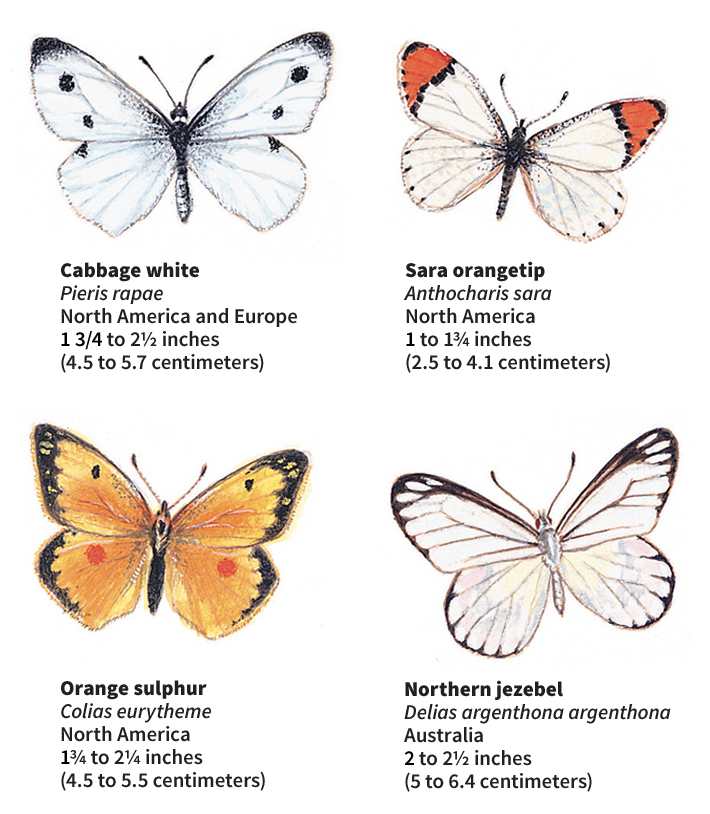

live around the world. Most of them live in tropical regions, but members of this family reach the shores of the Arctic Ocean. Others fly at 16,000 feet (4,900 meters) above sea level in the Andes Mountains of South America and the Himalaya of Asia. Sulphurs range in color from light yellow to orange. They are named for the mineral sulfur, which is powdery yellow. The wings of most sulphurs have black edges.

Whites have white wings that may be marked with black, brown, yellow, or red spots. Some have green markings below. The cabbage butterfly is the most common white. The caterpillar of this species is a major pest that feeds on cabbage, cauliflower, and related plants.

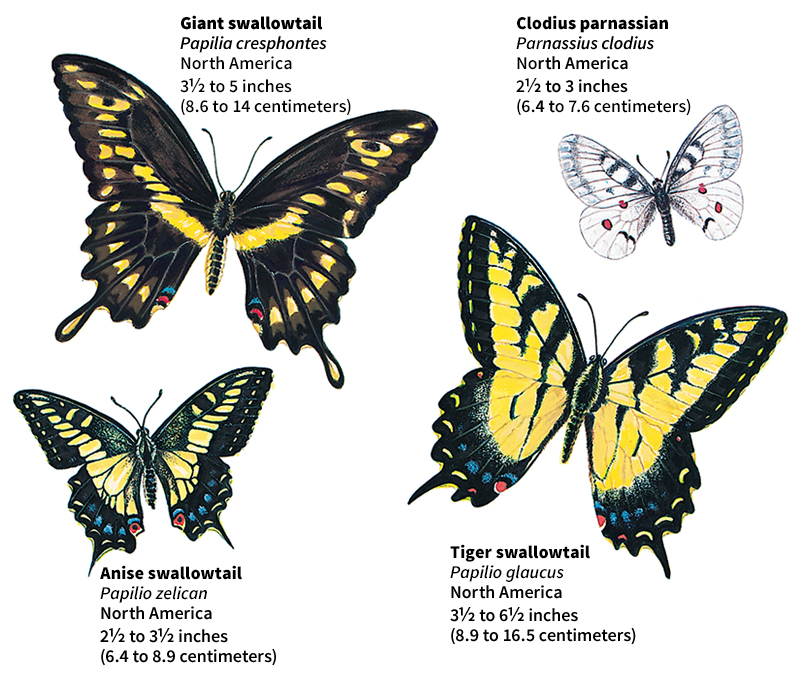

Swallowtails

are found worldwide, though most species live in the tropics. Swallowtails are among the largest and most beautiful butterflies. They include Queen Alexandra’s birdwing, the largest of all butterflies, and the African giant swallowtail, which has a wingspread of up to 10 inches (25 centimeters). Most swallowtails have a long extension on each hind wing. The butterflies get their name from these extensions, which resemble the tails of birds called swallows.

Most swallowtails are black, brown, and yellow with red and blue spots on their hind wings. One group, the parnassians, has white or creamy wings with red and black spots. Parnassians do not have “tails.” Well-known species of swallowtails include the giant swallowtail and the tiger swallowtail.

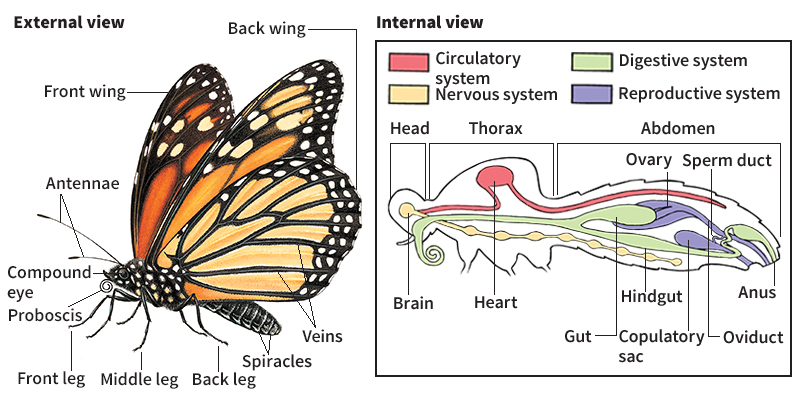

The bodies of butterflies

Butterflies have certain body features in common with other insects. For example, a butterfly has a hard, shell-like skin called an exoskeleton. The exoskeleton supports the body and protects the internal organs. A butterfly’s body, also like that of any other insect, has three main parts: (1) the head, (2) the thorax, and (3) the abdomen.

The head

is the center of sensation. It bears a butterfly’s (1) eyes, (2) antennae, and (3) mouthparts.

Eyes.

On each side of its head, a butterfly has a large compound eye, which consists of thousands of tiny lenses. Each lens provides the insect with an image of part of its surroundings. The brain combines the separate images into a complete view. Butterflies can see ultraviolet (UV) light, a kind of light invisible to human beings. Some flowers and butterflies have special markings that reflect UV light. For example, the wings of male orange sulphur butterflies reflect UV light. To a butterfly, the wings do not look orange but rather a color called bee purple.

Antennae.

Two long, slender antennae grow between the eyes. The antennae are organs of smell. A butterfly uses its sense of smell to locate food and to find mates. The antennae probably also serve as organs of hearing and touch.

Mouthparts.

A butterfly caterpillar has chewing mouthparts that consist of two lips and two pairs of jaws. These structures re-form as the caterpillar changes into an adult butterfly. One pair of jaws nearly disappears. The other pair becomes a long sucking tube, called a proboscis, that coils up when not in use. The lips form a protective covering for the proboscis.

A butterfly uses its proboscis to suck nectar and other liquids. Muscles in the head help the insect draw fluid up the proboscis and into a cavity in the head. A covering on the end of the proboscis closes and keeps fluid from flowing out. Other muscles force the fluid into the stomach.

The thorax

forms the middle section of a butterfly’s body. A short, thin neck connects it to the insect’s head. Attached to the thorax are a butterfly’s (1) wings and (2) legs.

Wings.

A butterfly has a pair of front wings and a pair of back wings. Veins filled mainly with air run through the wings and serve as wing supports. The wings are stiff near the front edges and at the bases. The outer margins of the wings are flexible. They bend when flapped in flight. This bending pushes the air backward and moves the butterfly forward. The front margins of the wings give the insect “lift” as it flies forward.

Butterflies and moths cannot fly if their body temperature is less than about 86 °F (30 °C). At lower temperatures, they must “warm up” their flight muscles by sunning their bodies or by shivering their wings.

The size of a butterfly’s body and wings determines how the insect flies. For example, milkweed butterflies and swallowtails have small, lightweight bodies and large wings. These butterflies can fly by beating their wings slowly. They are excellent gliders and can fly great distances. On the other hand, skippers have large, heavy bodies and small, pointed wings. They must beat their wings rapidly to stay aloft. Skippers do not soar or glide, but they can fly swiftly for short distances.

A butterfly’s wings are covered with tiny, flat scales that overlap. The scales provide color and form patterns. Most scales contain pigment (coloring matter). Colors produced by pigment include black, brown, red, white, and yellow. Other kinds of scales produce color by reflecting light from their surfaces. Shiny, metallic colors, such as shimmering blue and green, are made in this way.

Legs.

Butterflies have three pairs of legs. Each leg has five main segments. Joints between the segments enable a butterfly to move its legs in various directions. Each leg ends in a pair of claws and pads. The claws help to grip surfaces. The pads have hairlike structures used as taste organs. Butterflies have weak legs and can walk only short distances.

Among brush-footed butterflies, the front legs are quite short. These “brush feet” are useless for walking, but they hold highly developed taste organs.

The abdomen

chiefly contains a butterfly’s reproductive organs. It also has organs for digesting food and for getting rid of waste products.

The internal organs

of butterflies are grouped into five main systems: (1) circulatory, (2) nervous, (3) respiratory, (4) digestive, and (5) reproductive.

The circulatory system

carries blood throughout the body. It consists of a long tube that lies just under the exoskeleton of the back. The tube extends from the head to the end of the abdomen. The heart, the pumping part of the tube, lies in the thorax. The blood empties out of the tube into the head. It then floods the entire body. The blood reenters the tube through little openings along the sides. A butterfly’s blood is yellowish, greenish, or colorless. It carries food, but not oxygen, to the cells of the body.

The nervous system

of butterflies consists of a brain, in the head, and two nerve cords that run through the thorax and abdomen. Along the cords, bundles of nerve cells called ganglia branch out to all parts of the body.

The respiratory system

brings oxygen to the cells of the body and takes away carbon dioxide. Oxygen enters through tiny holes along the sides of the body, called spiracles. Each spiracle connects to a tubelike structure called a trachea. The tracheae branch out to all the cells of the butterfly’s body. In this way, the body cells obtain oxygen directly from the air rather than from the blood.

The digestive system

is basically a long tube that extends from the mouth to the anus, an opening at the end of the abdomen. Nectar passes from the proboscis into the gut, where nourishing substances in the food are absorbed. The remaining waste products pass through the hindgut and out of the body through the anus.

The reproductive system.

Butterflies reproduce sexually—that is, a new butterfly is created by uniting a sperm (male sex cell) and an egg (female sex cell). Female butterflies have a pair of organs, called ovaries, in which eggs develop. Males have two sperm-producing organs, called the testes. These are fused to resemble a single structure. A tube carries sperm from the testes to another tube that extends outside the abdomen. The male places the sperm into an organ in the female called the copulatory sac. The sperm duct transports the sperm to a tube called the oviduct, where fertilization takes place.

The life cycle of butterflies

The life of an adult butterfly centers on reproduction. The reproductive cycle begins with courtship, in which the butterfly seeks a mate.

Butterflies use both sight and smell in seeking mates. Either the male or the female may give mating signals called cues. The cues must be of a certain kind or in a particular order. If a butterfly presents the wrong cue or cues in the wrong order, potential mates will reject it.

In courtship involving visual cues, a butterfly reveals certain color patterns on its wings in a precise order. Many visual cues involve the reflection of UV light from a butterfly’s wing scales. The cues are invisible to the human eye, but butterflies see them clearly. The visual cues help the insects distinguish between males and females and between members of different species.

Usually, a female butterfly that presents an appropriate scent will be immediately accepted as a mate. The scent comes from chemicals called pheromones. The pheromones may be released from special wing scales called androconia. In most butterflies, both sexes use pheromones. However, the pheromones work only at close range, after the male has found the female by sight. In a few butterflies, an airborne pheromone may attract a male from a great distance.

In mountainous areas, males and females often fly to rocky summits to find mates. Such behavior is called hilltopping.

After mating, the female goes off in search of a place to lay her eggs. She usually begins laying the eggs within a few hours after mating. The male may mate several times during his life, but most females mate only once.

Every butterfly goes through four stages of development: (1) egg, (2) larva, (3) pupa, and (4) adult. This process of development through several forms is called metamorphosis.

The egg.

Butterfly eggs vary greatly in size, shape, and color. Some eggs are almost invisible to the human eye. The largest ones are about 1/10 inch (2.5 millimeters) in diameter. The eggs may be round, oval, cylindrical, or other shapes. Most are green or yellow. A few species have orange or red eggs. Some eggs are smooth. Others have ridges and grooves.

Most female butterflies lay their eggs on plants that will provide the offspring with food. Before depositing the eggs, the female may “taste” a plant with special organs on the ends of her front legs to make sure the plant is suitable. Some females lay their eggs near a plant or drop them at random while flying. After hatching, the young must find the food themselves.

While laying the eggs, the female fertilizes them with sperm stored in her body from mating. Each egg has a small hole through which sperm may enter. Depending on the species, a female may lay several dozen eggs or clusters of hundreds. A sticky substance deposited with the eggs helps hold them on the plant. The eggs of some butterflies hatch in a few days, but others take months. Eggs laid in fall may not hatch until spring.

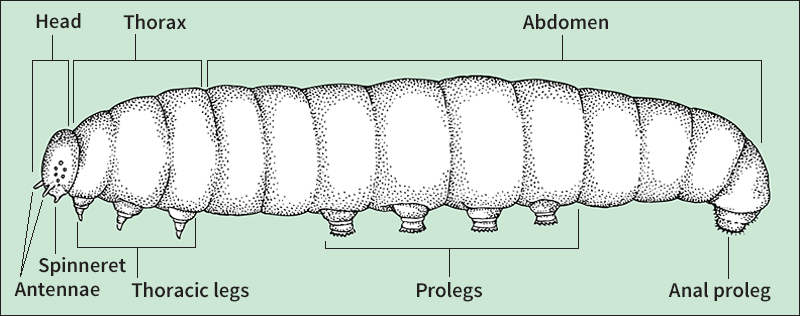

The larva,

or caterpillar, emerges from the egg and immediately begins its main activity—eating. A caterpillar’s first meal is usually its own eggshell. It then begins to eat the nearest food. The majority of caterpillars feed on green plants. Some caterpillars eat insects, such as aphids. A few live inside ant nests and eat ant larvae. In one day, a caterpillar may eat many times its weight in food. Much of this food is stored in the body. It is used for energy in later stages of development.

Most caterpillars are solid green or brown. Many others have patterns of yellow, red, or other bright colors. Some caterpillars have smooth skin. Many others have bristles, bumps, fleshy knobs, or eyespots. All these features help protect caterpillars from being eaten by making them hard to see or frightening in appearance.

A caterpillar’s body consists of 14 segments. The first segment, the head, includes chewing mouthparts and two short, thick antennae. The head also has six small eyes on each side. The eyes cannot see images, but they help the caterpillar distinguish between light and dark.

The next three segments of the caterpillar’s body make up the thorax. Each of these segments has two short, jointed legs with a sharp claw at each tip. The remaining 10 segments form the abdomen. Most caterpillars have a pair of false legs, known as prolegs, on the seventh, eighth, ninth, and tenth body segments. At the end of each proleg are tiny hooks. The last segment has a pair of suckerlike legs called anal prolegs or anal claspers. These specialized legs enable the caterpillar to cling to plants and to move about.

A short structure called a spinneret sticks out below the caterpillar’s mouth. It releases a sticky liquid. The liquid hardens into a silken thread, giving the caterpillar a foothold wherever it goes. Like the adult, the larva breathes through spiracles on the sides of the body.

The larval stage lasts at least two weeks. During that time, the caterpillar grows rapidly. Its exoskeleton, however, does not grow. Instead, the caterpillar forms a new skin beneath the exoskeleton. When the exoskeleton becomes too tight, it splits lengthwise along the back. The larva then crawls out. The new skin is soft, and the larva stretches it to provide growing room. The larva then lies motionless a few hours as the skin hardens into a new exoskeleton. Most caterpillars molt—that is, shed their exoskeletons—four or five times.

The pupa.

After a caterpillar reaches its full size, it is ready to become a pupa. In preparation for this stage, most moth larvae spin silken cocoons around themselves. However, only a few butterfly species spin cocoons. Instead, the typical butterfly caterpillar finds a sheltered spot, usually high on a twig or leaf. There, it deposits sticky liquid from its spinneret, which quickly hardens into a silken pad. The exoskeleton then begins to split near the head, and the pupa starts to emerge. As the exoskeleton falls from the tail, the pupa thrusts its cremaster into the pad. The cremaster is a many-clawed structure at the end of the abdomen. This procedure is dangerous. If the butterfly does not grasp the pad fast enough, the pupa may fall to the ground and die.

Many pupae hang head downward, supported only by the cremaster hooked into the silken pad. Other pupae are positioned head upward. Such a pupa has an additional support of silken thread spun around the thorax and the twig or leaf to which it is anchored.

The pupa is soft at first, but a hard shell immediately begins to form over it. Some shells have unusual shapes and colorful patterns. In some cases, the shell has a golden shimmer. For this reason, scientists call the pupa a chrysalis. This word comes from a Greek word that means gold. Loading the player...

A caterpillar changes into a butterfly

The pupa is motionless and is often referred to as being inactive or at rest. However, much activity occurs within the shell. There, larval structures break down and re-form into those of an adult butterfly. Only some internal organs remain basically the same.

The pupal period ranges from a few days to more than a year, according to when the pupa forms and the species of butterfly. Many species spend the winter as pupae and emerge as adults in the spring.

The adult.

After the adult butterfly has formed, its body gives off a fluid that loosens it from the pupal shell. The thorax swells and cracks the shell. The head and thorax then emerge. Next, the butterfly pushes its legs out and pulls the rest of its body free. The entire process may take only a few minutes.

The exoskeleton of the emerging butterfly is soft. The wings are damp and crumpled. The proboscis is split in half lengthwise. The butterfly uses its muscles to pump air and blood through its body and wings. The butterfly’s exoskeleton hardens, and the legs and other body parts become firm. The wings flatten and expand. The butterfly joins the halves of its proboscis by coiling and uncoiling them repeatedly. About an hour after leaving the pupal shell, the adult butterfly may be ready to fly.

Most adult butterflies live only a week or two, but some species may live up to 18 months. Most butterflies feed only on nectar. Nectar provides quick energy, but it does not contain the proteins necessary for long life. Certain butterflies obtain proteins by feeding on decaying animal matter or on pollen. A number of butterflies do not feed. Instead, they live on food stored during the larval stage.

How butterflies protect themselves

Many predators, including other insects and birds, eat butterflies. But butterflies have developed various means to protect themselves.

Many butterflies and caterpillars blend with their surroundings. This form of defense is known as cryptic coloration. Adult butterflies may look like bark or other vegetation. Green caterpillars blend with the plants they eat. Brown ones look like dead leaves or twigs.

Many butterflies have chemical defenses. Such insects include the caterpillars of certain swallowtails. When disturbed, these insects give off an unpleasant odor from an organ just behind the head. Some butterflies taste bad, discouraging predators. As caterpillars, many of these butterflies eat plants with bitter or poisonous juices. They store the juices in body tissues, giving the flesh an unpleasant taste. If eaten by predators, these butterflies may cause vomiting. Most such butterflies also have bright colors to warn predators. An animal that has eaten one of these butterflies will probably avoid eating another butterfly with that coloration. This form of protection is called warning coloration.

Hibernation and migration

Butterflies cannot be active in cold weather. They must either hibernate or migrate to warmer areas.

Hibernation.

Many species of butterflies survive the winter by hibernating in a sheltered place. Butterflies may hibernate in the egg, larval, pupal, or adult stage. But each species usually hibernates in only one stage.

Just before hibernation, the blood of a larva, pupa, or adult produces substances called glycols. Glycols are chemically similar to the antifreeze used in automobiles. The presence of glycols enables a butterfly to survive even severe cold. When warm weather returns, other blood substances gradually replace the glycols.

Migration.

Some butterflies escape cold weather by migrating to a warmer region. Migrating butterflies include the buckeye, the California tortoiseshell, the cloudless sulphur, the painted lady, and the red admiral.

One species, the monarch, migrates farther than any other butterfly. Dense clouds of monarchs may travel up to 2,000 miles (3,200 kilometers) from Canada and the northern United States to a mountainous region in central Mexico. In western North America, monarch butterflies spend the winter on the coast of California.

Loading the player...Monarch butterfly

In the tropics, there is no winter. But many tropical regions have dry and rainy seasons. Butterflies in these areas often migrate by the millions, following patterns of plant growth caused by the rains. Such migrants include many whites and sulphurs. In India, hundreds of species migrate with the rains, including the common albatross, the common emigrant, and the dark blue tiger.

Butterflies and the environment

Butterflies fill important roles in many ecosystems. An ecosystem includes the things that live in an area as well as their relationships with one another and their environment. Unfortunately, some butterfly species have become endangered, and many more are in decline. Scientists worry that the disappearance of butterflies could do great harm to many ecosystems.

Butterflies and ecosystems.

Butterflies help maintain ecosystems in a number of ways. For example, butterfly caterpillars feed on plants of certain species. This feeding reduces the competition faced by other plant species, influencing which plants flourish in an area.

Butterflies also provide food for a variety of predators. Many birds, insects, and spiders eat adult butterflies or caterpillars. Other insects feed on butterfly eggs. Certain species of wasps and flies, called parasitoids, lay their eggs in or on butterfly eggs or caterpillars. When the eggs hatch, the larvae eat their hosts from within.

In addition, butterflies help pollinate flowers. In fact, butterflies may rank second only to bees as pollinators. Butterflies pollinate garden flowers, such as lantana and butterfly bushes; crops, such as apples and sunflowers; and wild plants, including many tropical flowers. A few plants, such as the North American yellow-tailed orchid, are pollinated exclusively by butterflies.

If plants pollinated by butterflies decline, animals that depend on the plants for food may decline in turn. This is just one way the loss of butterflies may have far-ranging consequences for an entire ecosystem.

Butterflies and environmental change.

Butterfly numbers are in rapid decline in many parts of the world. Highly specialized butterflies, such as species that feed on only a single kind of plant, are at greatest risk. However, even formerly common and widespread species are in decline. The greatest cause of butterfly decline is the loss of habitat, the places where butterflies live. Human beings have damaged or destroyed much butterfly habitat by replacing wild meadows with buildings or cropland. In many areas, remaining habitats have become widely separated, a condition called habitat fragmentation. Habitat fragmentation makes it more difficult for butterflies to find mates and food, to spread and migrate, and to meet other survival needs.

Global warming can also harm butterflies. As climates become warmer, habitats suitable for butterfly species are shifting. In areas already suffering from habitat fragmentation, butterflies may not be able to find new habitats. In mountainous regions, species adapted to cool climates must move higher up the mountain slopes. Eventually, even the mountain summits may become too warm. See Global warming.

Other threats to butterflies include air pollution and pesticides. Pesticides used to fight harmful insect pests also kill harmless or beneficial butterflies. Automobiles on busy highways also kill many butterflies.

Butterfly conservation.

Many people are working to protect butterflies. In some areas, laws protect endangered butterflies, making it illegal to collect them. Laws may also protect butterfly habitat.

Some people raise colorful or unusual tropical species on butterfly farms. This farming helps to protect wild butterflies and also provides a source of income for farmers, who sell the butterflies to collectors.

In many areas, the native plants on which caterpillars and butterflies feed have nearly disappeared. To help butterflies survive, many people have planted “butterfly gardens” made up of native plants. Even in dense cities, butterfly gardens can help butterflies to survive.

To help butterflies cope with global warming and habitat fragmentation, people have begun to establish nectar corridors. Nectar corridors are continuous areas of native plants that connect larger wild areas. The plants in nectar corridors provide food for caterpillars and adult butterflies. Such corridors enable migratory butterflies to move safely through the environments people have created. Nectar corridors also enable butterflies to find new homes when their old habitat becomes unsuitable.