Byzantine Empire developed from the Roman Empire starting in the A.D. 300’s. It survived for more than a thousand years, until the mid-1400’s. Its people called themselves Romaioi (Romans), but the Byzantine Empire gradually moved away from its initial cultural, geographical, and political identity with the ancient Roman world. Over time, the Byzantine Empire occupied a steadily decreasing territory around the eastern Mediterranean Sea and on the Balkan Peninsula. At the same time, its culture became strongly Christian.

Way of life

Government.

Throughout its history, the Byzantine Empire was governed by an emperor who was, in theory, an absolute ruler. Beneath him, senior church and court officials controlled an elaborate and extensive system of civilian, military, and religious government.

The people and their work.

Although Greek became the common language of the empire, many different peoples lived within its territories. The majority were poor peasant farmers who grew such crops as grapes, olives, and wheat, and raised such livestock as goats or sheep. They lived in small houses that were typically built of wood or mud-brick. They wore coarse, simple clothes. Their diet consisted mainly of bread, cheese, olive oil, and vegetables.

Wealthy Byzantines and those of high birth lived in stone mansions. They wore long robes of silk and other luxurious fabrics. Many of the dishes that they ate contained fish or meat cooked in strongly flavored sauces.

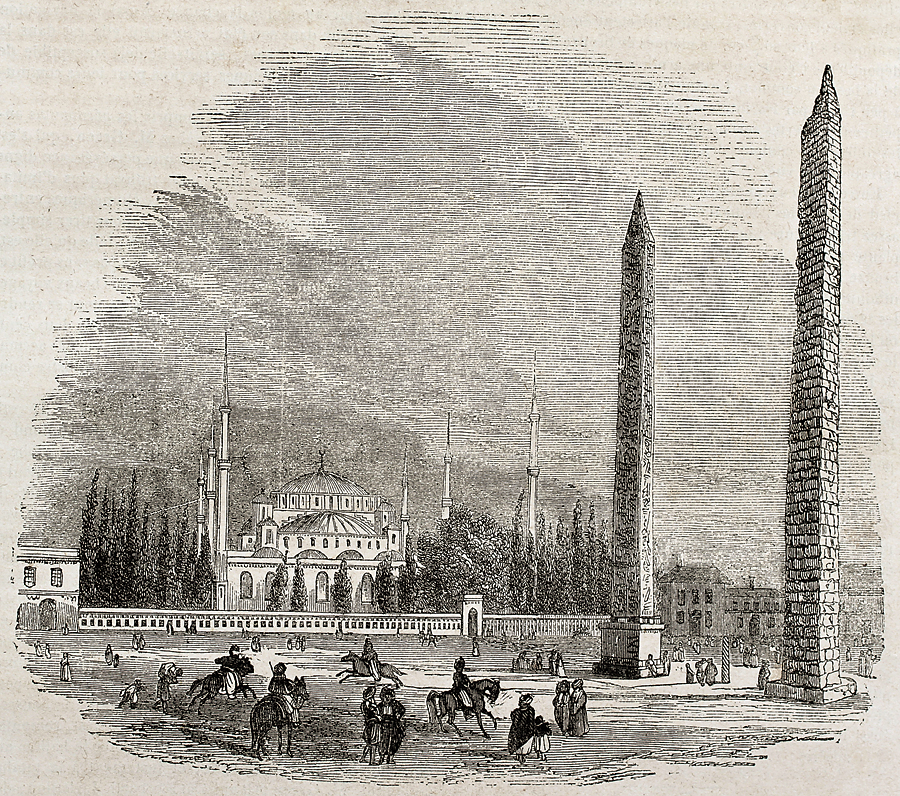

Relatively few people lived in cities. However, the capital, Constantinople (now Istanbul, Turkey) was a large urban settlement throughout Byzantine history. At its peak, the city housed about half a million people. Craftworkers typically plied their trades in towns and cities, processing the materials and producing the goods that were necessary for daily life. They also produced elaborate decorative works in ceramic, ivory, metal, textiles, and wood. Byzantine merchants who traded in towns and cities imported such luxury goods as furs, silks, and spices from as far away as China and Russia. They also traded such basic goods as metals and timber. The Byzantine Empire had a flourishing slave trade, especially in the empire’s early and middle years.

Recreation.

Ancient Roman traditions of public entertainment and recreation were popular, especially during the early centuries of the Byzantine Empire. These traditions included the use of public baths as well as chariot racing and other spectacles. The Christian church disapproved of these traditions, and they gradually became less common.

Society.

Social distinctions were important to the Byzantines. However, it was possible for people who began life at the bottom of society to reach the top. Education and military service, in particular, provided a way to improve one’s social standing. Most women, especially those in upper-class or wealthy families, were largely confined to domestic roles, such as child rearing, household management, spinning, and weaving. They lived in partial seclusion and could only appear in public under certain circumstances. Some women, however, occupied influential public roles. On a few occasions, women ruled the empire. Empress Theodora, the wife of Emperor Justinian I, was one of the most powerful women of the Byzantine Empire.

Education.

The majority of Byzantines received little education. However, basic reading and writing skills were more common in the Byzantine Empire than in Western Europe at the same time. More advanced education was available for those in the government, and specialists received an education in such subjects as law, mathematics, medicine, Greek, and especially Christian literature. Byzantine scholarship significantly influenced the Muslim and Slavic worlds. It also played an important role in the European Renaissance, a revival of interest in classical culture that began in the 1300’s.

Religion.

Constantine the Great, commonly considered the first Byzantine emperor, strongly supported Christianity and was baptized a Christian shortly before his death in A.D. 337. During and after Constantine’s reign, Christianity spread throughout Byzantine society and replaced polytheism (belief in many gods). Christianity transformed most of the empire’s institutions. It also introduced new ones of its own. For example, the church established its own hierarchy (organization by rank). A form of religious community life known as monasticism became widespread.

The influence of Christianity is particularly evident in Byzantine art, including architecture and literature. Byzantine art featured pictures of holy people that stressed the sacred quality of the subject, rather than the human quality. The Byzantines also designed elaborately decorated domed churches. In addition, the Byzantines produced valuable works in history and wrote fine poetry, including religious poems. They also created much religious prose. Today, the Eastern Orthodox Churches carry on the Byzantine religious tradition.

History

Beginnings.

The beginning of the Byzantine Empire commonly is dated to A.D. 330. That year, Constantine dedicated the ancient Greek city of Byzantion, also known as Byzantium, as a new imperial residence and capital. The city, which was renamed Constantinople after Constantine, soon became the political center of the entire Roman Empire.

The late Roman period.

The first period of Byzantine history lasted from the early 300’s to the mid-600’s. It is often called the late Roman period or Late Antiquity.

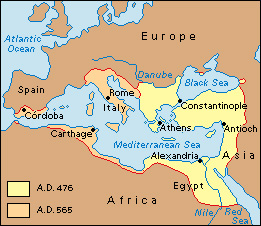

After Emperor Theodosius I died in 395, the Roman Empire formally split into the West Roman and East Roman empires. The West Roman Empire grew weaker, and Germanic peoples began to establish small kingdoms within it. In 476, its last emperor was overthrown. The East Roman Empire survived as the Byzantine Empire.

The early Byzantine Empire kept many elements of the administration, culture, and economy of the Roman Empire. Later, particularly from the mid-500’s, these elements began to be lost. For example, the importance of the independent governmental unit called a polis or city-state declined. Greek replaced Latin as the official language, and administrative and military systems were reorganized. Artistic interests and styles also changed.

In the mid-500’s, Emperor Justinian I organized extensive military campaigns that, for a short time, regained control over former Roman territory in Italy, North Africa, and Spain. Over the next hundred years, however, new invasions by the Avars, Lombards, Slavs, and other groups in Italy and the Balkan Peninsula isolated Byzantium from most of its old Western territories. The emergence of Islam on the Arabian Peninsula in the early 600’s, and the rapid expansion of the Arab empire ended Byzantine control of Syria, Palestine, Egypt, and North Africa by the end of the 600’s.

Loss and transition.

The period from the mid-600’s to the mid-800’s was one of difficult transition for the Byzantine Empire. For this reason, it is sometimes called the Byzantine dark age. The empire’s territory was reduced to little more than western Asia Minor and the coastal regions of the Balkan Peninsula and Greece. To the east, the Byzantines continued to resist attacks by Muslim Arabs. The Bulgars established themselves as a new military and political rival north of the Balkan Peninsula.

During this period, the urban culture typical of the ancient world seems to have largely disappeared. At the same time, the administrative, economic, and social organization of the empire changed dramatically.

In the early 700’s, a movement known as iconoclasm swept through the empire’s political and religious organizations. The word iconoclasm comes from Greek words meaning the destruction of images. By this time, the use of religious images called icons had become popular in Christian worship. Several Byzantine emperors in the 700’s and early 800’s tried to enforce a ban on icons while trying to reestablish the empire’s central authority at Constantinople.

The middle period

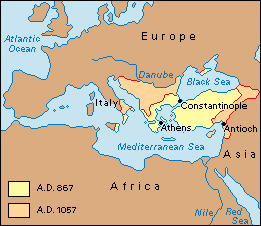

of Byzantine history lasted from the late 800’s to the early 1200’s. During this period, the Byzantine Empire reestablished itself as a significant economic and political power in the Balkan and eastern Mediterranean regions.

From 867 to 1056, the Macedonian dynasty (series of rulers) founded by Emperor Basil I ruled the empire from Constantinople. Under this increasingly centralized and powerful regime, the Byzantines reestablished administrative and political control over a large geographical area. After many struggles, the Byzantines gained control over the Balkan region and extended their influence as far north as Russia. Military campaigns pushed the empire’s eastern frontier back into Armenia and Syria. The Byzantines also regained control of the Aegean and Mediterranean seas from the Arabs.

A marked cultural and economic revival accompanied the development of political stability. Towns expanded, and trade flourished. Christian culture remained dominant, but some artists and writers developed a new interest in the traditions of ancient Greece and Rome.

From the death of Basil II in 1025 to the 1080’s, the Byzantine Empire struggled against a number threats. The Macedonian dynasty failed, and provincial families with wealth and military strength tried to seize power in Constantinople. Meanwhile, new enemies appeared at the borders of the empire. They included the Seljuk Turks in Asia Minor and the Normans in southern Italy. In addition, the office of the pope in Rome was beginning to emerge as a serious rival to Byzantine ideas of political and religious supremacy.

In 1054, disagreements between Byzantine and Western theologians (religious scholars) over authority and practice in the church led to a schism (formal break) between the eastern and western sections of the church. Members of the western section came to be known as Roman Catholics. Those in the east eventually became known as Eastern Orthodox Christians.

In 1071, the Normans finally forced the Byzantines out of Italy. That same year, the Seljuks defeated the Byzantines at the battle of Manzikert in eastern Asia Minor.

In 1081, Emperor Alexius I Comnenus established a new Byzantine dynasty. Under Alexius I and his descendants, the Byzantine Empire enjoyed an extended period of relative prosperity and stability, as well as cultural and intellectual activity.

In 1095, Alexius I asked Pope Urban II for assistance in fighting the Muslim Seljuks, who then controlled Asia Minor and Palestine. Both Christians and Muslims considered Palestine a holy land. The pope and other Western European powers sent a series of Christian military expeditions, called Crusades, to Palestine. From 1099, the Crusades established Western European control over the coastal regions of much of the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Over time, serious differences developed between the Western European crusaders and the Byzantines. During the Fourth Crusade (1202-1204), the crusaders became involved in political affairs of the Byzantine Empire. In 1204, they captured and sacked Constantinople and established a new Latin Empire there. See Crusades.

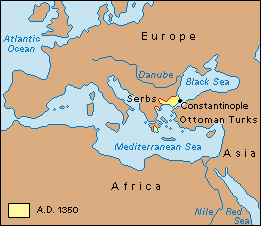

The late Byzantine period.

After the formation of the new Latin Empire, rival Byzantine powers set up governments in exile in northern Greece and western Asia Minor. In 1261, the Byzantine general Michael VIII Palaeologus recaptured Constantinople. He then founded a new dynasty that ruled for nearly 200 years. During that period, however, Byzantine territory was reduced to little more than small pockets of land around Constantinople and in southern Greece. For most of this period, the empire fought for its survival against such neighboring powers as the Serbs and the Ottoman Turks. The empire also was engaged in a series of bitter civil wars. Nevertheless, the final period of the Byzantine Empire was one of great artistic and intellectual achievement and saw the emergence of a new Greek identity. The empire came to an end in 1453, when the Ottomans captured Constantinople.