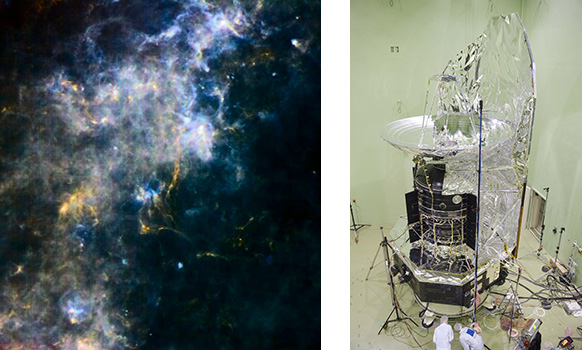

Herschel Space Observatory was a space telescope that made observations in far-infrared light. Infrared light has wavelengths slightly longer than those of visible light. Far infrared consists of the portion of infrared light with the longest wavelengths. Far-infrared light is ideal for observing the formation of galaxies, seeing through regions clouded by gas and dust, and viewing the formation of stars and their planets. Herschel was launched on May 14, 2009, on the same rocket as another space observatory, named Planck. Herschel ceased operation on April 29, 2013. It was named after the British astronomer Sir William Herschel.

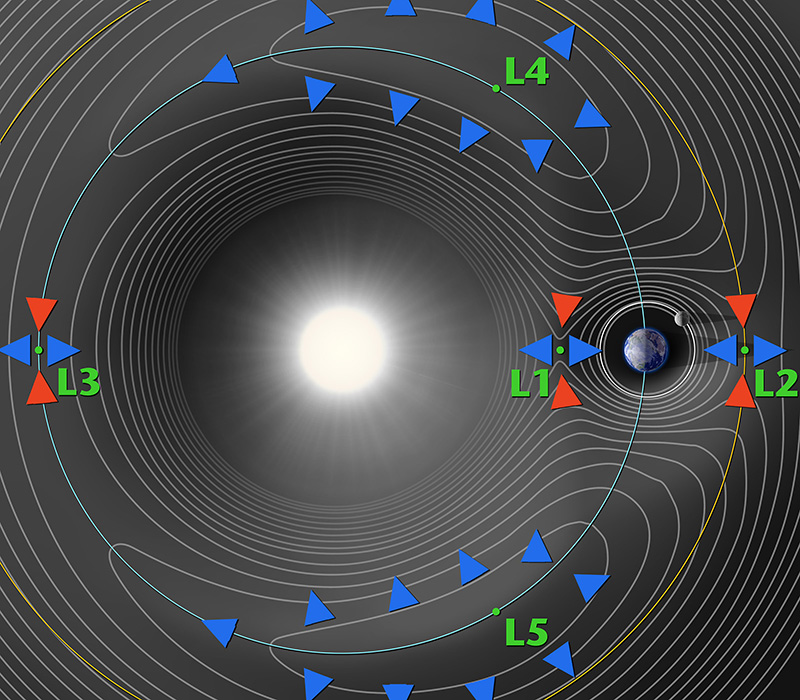

Herschel still orbits the sun near the second Lagrange point associated with the sun-Earth system (L2), a point 900,000 miles (1.5 million kilometers) from Earth (see Lagrange point ). The Herschel telescope gathered light using a mirror 111/2 feet (3.5 meters) in diameter.

Galaxies undergoing rapid star formation can give off more far-infrared light than visible light. Although they are rare among nearby galaxies, such far-infrared galaxies were much more abundant and bright in the early universe. Herschel observed these distant early galaxies to help understand their formation.

Herschel also studied the interstellar medium, the gas and dust between the stars. Starlight slightly heats the dust between the stars. This cold dust is best observed in far-infrared light. Observing atoms and molecules at far-infrared wavelengths can tell astronomers the temperature and density of interstellar gas. Stars and their planetary systems form from clouds of cold interstellar gas and dust. These clouds give off far-infrared light as gravity causes them to become smaller and denser. Astronomers can use this light to spot regions where the first stages of star formation may be happening. At later stages in star formation, a disk of dust and gas continues to surround the forming star. This disk may eventually form planets. Far-infrared light from this disk can give astronomers information about how planetary systems form.

The Herschel spacecraft and its instruments were cooled to an extremely low temperature. This kept the equipment from giving off heat in the form of infrared rays, which would have interfered with observations. The instruments were cooled to near absolute zero using liquid helium. Absolute zero is the coldest possible temperature, –273.15 °C or –459.67 °F. The helium slowly evaporated.

In early 2010, scientists reported the results of Herschel’s first observations. Among the results were several discoveries concerning star formation and the relationship between galaxies and the super-massive black holes found in their centers. Later discoveries include the observation of two massive galaxies merging, finding a layer of water vapor around Jupiter created when the comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 struck the planet in 1994, and the observation of a massive “star factory” galaxy producing new stars at the tremendous rate of about 2,900 per year.

On April 29, 2013, the craft exhausted its supply of helium coolant, ending the telescope’s scientific observations. The telescope was then placed into a solar orbit where it will remain for at least several hundred years. Several European countries, Canada, China, Israel, Taiwan, and the United States contributed to the development and construction of Herschel.