Saint-Mihiel, Battle of, was a United States -led assault on German forces during World War I (1914-1918). The battle began on Sept. 12, 1918, near St-Mihiel, a town in northeastern France . St-Mihiel was a key position on the Western Front, the battlefront running through Belgium and northern France. The battle ended on September 16 with an American victory. Though it had Allied support, the assault at St-Mihiel was the first major independent offensive by the American Expeditionary Forces ( A.E.F. ) sent to Europe during the war. The victory boosted Allied morale and brought Germany closer to surrender.

Background.

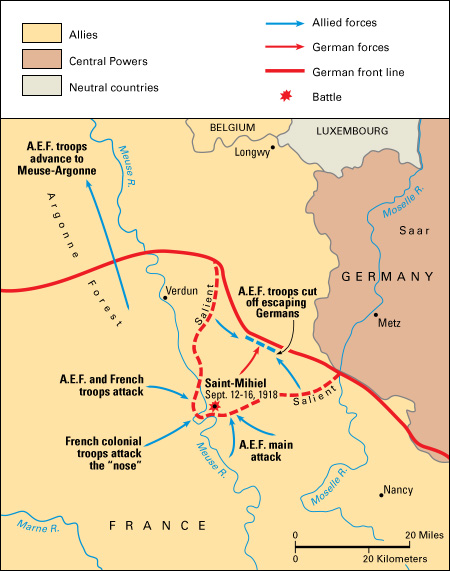

German troops captured St-Mihiel in September 1914. The city lay at the tip of a salient, a triangular outward bulge in the German front line, between the cities of Verdun and Nancy. In 1915, French forces suffered 125,000 casualties (people killed, wounded, missing, or captured) in unsuccessful efforts to reduce the St-Mihiel salient.

The United States entered the war against Germany in April 1917. In the spring of 1918, a massive German offensive broke the deadlock of trench warfare (fighting from fortified ditches) on the Western Front. Allied troops—strengthened by July by more than 1 million Americans—rallied to stop the Germans. In the summer, the Allies counterattacked and began advancing all along the front.

In August, the U.S. First Army, led by General John J. Pershing , took over positions just south of St-Mihiel. In preparation for the St-Mihiel assault, additional U.S. combat and support units arrived from around France. The U.S. force of about 550,000 troops was assisted by about 110,000 French colonial troops. Nearly 1,500 Allied aircraft—including more than 1,100 combat warplanes—supported the attack. Consisting of U.S., French, British, and Italian air squadrons, the force was the largest collection of air power during the entire war. A U.S. tank brigade, led by Lieutenant Colonel George S. Patton, Jr. , also played a key role in the attack.

German defenses at St-Mihiel were strong. The Germans, however, were aware of the coming attack and began to withdraw on September 11. Short on reserves and reinforcements, they intended to abandon the salient in favor of a stronger line farther back. The U.S. attack caught many German troops in the open.

The battle.

After a heavy bombardment, U.S. infantry and tanks attacked early on September 12. The main attack came on the southern side of the salient. A few hours later, U.S. troops along with one French division hit the western side as French colonial forces attacked the salient’s “nose,” St-Mihiel. The advancing troops struggled through heavy German gunfire, barbed wire, and muddy ground. However, the Germans were soon overwhelmed. Within a few hours, the Americans and French had advanced as much as 5 miles (9 kilometers). They continued to advance throughout the day and night, taking a number of key positions.

Allied warplanes provided close air support, firing directly on enemy troops on the ground. They also hit German communications and reinforcements while attacking German warplanes far behind the front line. On September 13, U.S. troops advancing from the west and south met deep in the salient, cutting off German troops who had been unable to escape. American and French troops defeated the remaining Germans in the salient, gaining complete control by September 16.

Aftermath.

The American victory at St-Mihiel was quick and less bloody than many earlier battles of the war. American and French casualties totaled some 7,000. About 15,000 German troops became prisoners of war. Another 2,500 were killed or wounded. The reduction of the salient recovered roughly 200 square miles (520 square kilometers) of French territory.

After St-Mihiel, the U.S. First Army immediately reloaded for the much larger Meuse-Argonne Offensive to the northwest. In that battle, the Americans—again aided by the French—overcame fierce German resistance, fighting until the war’s end on November 11.