New York City draft riots of 1863 were among the most violent incidents of civil unrest in United States history. The riots took place in New York City in July 1863, during the American Civil War. They began as a reaction to the draft, or conscription, that selected people for required military service. Racial tensions also contributed to the violence. White mobs that opposed conscription first attacked military and government buildings. They soon turned their anger on police officers, the wealthy, and, especially, the city’s Black residents. During four days of rioting, more than 100 people were killed, and several hundred more were wounded. Hundreds of buildings were looted, burned, or otherwise damaged.

Background.

After the Civil War began in 1861, both the Union and the Confederacy passed conscription laws. In January 1863, President Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation took effect. The proclamation declared freedom for slaves in all areas of the Confederacy that were still in rebellion against the Union. It also allowed African Americans to join the U.S. Army and Navy.

In March 1863, the U.S. Congress passed the Enrollment Act, which introduced a federal military draft. Under the new law, the draft came to include single male citizens from 20 to 45, and married male citizens from 20 to 35. Draftees would be selected by a lottery conducted at draft offices in each congressional district. The draft excluded Black men because they were not considered citizens at that time. The law also allowed men to escape the draft by finding a substitute or paying the government a fee of $300, an amount well outside the reach of most working men.

At its outset, the war had been unpopular with New Yorkers, especially the white working class. By 1863, most residents of New York City supported the Union war effort. However, many of the city’s Democratic politicians remained opposed to the war and the draft. New York Governor Horatio Seymour, a Democrat, opposed the policies of President Lincoln, who was a Republican. Seymour argued that the conscription law demanded too much of New Yorkers. Many citizens resented the fact that the wealthy could “buy” their way out of military service for $300. Democratic-leaning newspapers aroused opposition to the draft and emancipation.

New York City at that time was experiencing tension between white residents—particularly Irish and German immigrants—and Black people. Many white people were concerned that free Black people would compete with them for jobs and housing. In the spring of 1863, striking Irish dockworkers had attacked Black strikebreakers—that is, workers who crossed picket lines to take strikers’ jobs. Racial relations in the city remained tense through the summer.

New York City’s first draft lottery drawings under the new law began on July 11. Newspapers published the names of drafted New Yorkers on July 12. The city remained peaceful on that hot July day, but conscription opponents planned activities to disrupt the draft. Crowds of white working-class men began to gather at neighborhood pubs.

The riots.

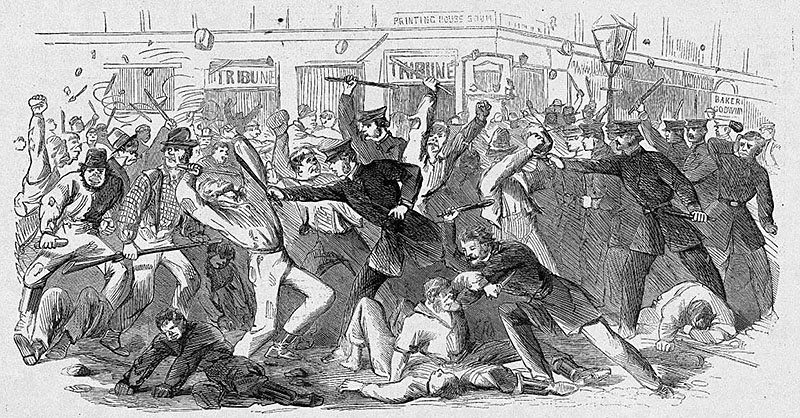

Soon after 6 a.m. on Monday, July 13, men began spilling out from the tenements in lower Manhattan. A crowd formed in the city. Many of the people were Irish laborers who opposed the draft. The crowd also included German craftsmen and working-class Protestants. Women soon joined the group in large numbers. The crowd marched to the site of the Ninth District draft lottery office, located southeast of Central Park at 46th Street and Third Avenue. The site was the office of the district’s provost marshal, a military official. Members of the crowd charged the building. They attacked workers inside and set the building on fire.

The mob soon turned its attention to other government buildings. Rioters attacked outnumbered police officers and other New Yorkers who attempted to stop the violence. Rioters cut telegraph wires to prevent local officials from requesting help from Union forces in Pennsylvania. By the afternoon, rioters began to target Black people and Black-owned businesses. They looted an orphanage for Black children and set it aflame. The children were able to escape only with the help of local militia, who used their bayonets to protect the children from the mob. Rioters also targeted the homes of Republican politicians.

Riots raged for three more days. Many Black families fled the city. Stores and factories closed, and idle workers joined the crowds. George Opdyke, the city’s Republican mayor, pleaded with Governor Seymour to send troops to the city. Many New York militia (citizens’ army) troops had been called away to assist Union Army efforts in Pennsylvania, where a major battle had recently been fought at Gettysburg. Federal officers did not have enough troops on hand to stop the rioting.

Seymour addressed the unruly crowds on July 14. He tried to calm the rioters by proclaiming his opposition to the draft law. Federal authorities suspended the law on July 15.

Large-scale violence ended in the city by Thursday, July 16. At Seymour’s request, Roman Catholic Archbishop John Hughes addressed crowds on Friday and urged an end to the rioting. By then, federal troops had arrived in the city and helped to restore order. Troops remained camped around the city for several weeks. Racial tensions persisted in the city long after the riots.