Canada, History of. Canada’s history is the story of the peoples who have inhabited and the forces that have shaped the second largest country in the world. Only Russia has a larger area. Most scientists think that people arrived in the Americas from Asia about 15,000 years ago, or earlier. They arrived by way of a land bridge that once connected Asia and North America at what is now Alaska. In Canada, their descendants became known as Indians, and later as First Nations. The ancestors of the Inuit arrived later, moving into the Arctic regions of Canada starting about A.D. 1000. Today, the First Nations and the Inuit are recognized as Indigenous (native) peoples of Canada. For details about the first Canadians, see First Nations; Indigenous peoples of the Americas; and Inuit.

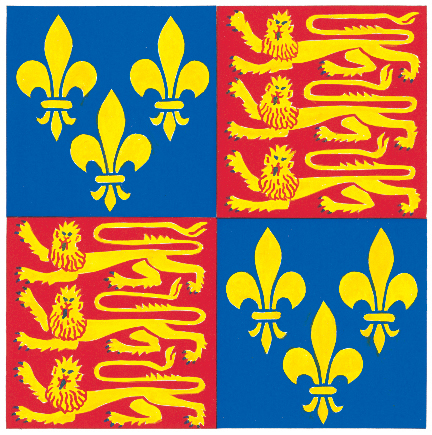

In 1497, John Cabot, an Italian navigator in the service of England, found rich fishing grounds off Canada’s southeast coast. In time, his discovery led to the European exploration of Canada. France took the lead in exploring the country and set up a colony in eastern Canada in the early 1600’s. French fur traders traveled westward and came upon many of Canada’s sparkling lakes, rushing rivers, and majestic, snow-capped mountains. Britain (now also called the United Kingdom) gained control of the country in 1763, and thousands of British immigrants began to join the French who remained in Canada. In 1867, the French- and English-speaking Canadians helped create a united colony called the Dominion of Canada. The two groups worked together to settle the country from coast to coast and to develop its great mineral deposits and other natural resources.

Canada gained its independence from Britain in 1931. During the mid-1900’s, hard-working Canadians turned their country into an economic giant. Today, huge harvests from western Canada make the nation a leading producer of wheat, oats, and barley. Canada also ranks among the world’s top manufacturing nations, and it is a major producer of crude oil, electric power, and natural gas.

Throughout its history, Canada has often been troubled by a lack of unity among its people. French Canadians, mostly from Quebec, have struggled to preserve their French culture. They have long been angered by Canadian policies based on British traditions, and some of them support a movement to make Quebec a separate nation. People in Canada’s nine other provinces often favor local needs over national interests.

Canada and the United States have generally enjoyed a long history of cooperation. They have worked together in the defense of North America and have strong economic ties. Canada has tried to develop independently of its southern neighbor. But its economy is so closely linked to the U.S. economy that severe U.S. business slumps usually cause hard times in Canada. In addition, the popularity of U.S. culture in Canada has challenged the efforts of Canadian leaders to establish a separate identity for their country.

For information on the people, economy, and government of Canada today, see the articles Canada and Canada, Government of.

Early European exploration

About A.D. 1000, Vikings from Iceland and Greenland became the first known Europeans to reach North America. The Vikings, led by Leif Eriksson, landed somewhere on the northeast coast, a region the explorer called Vinland. The Vikings established a colony in Vinland, but they lived there only a short time. Ruins of a Viking settlement have been found at L’Anse aux Meadows, on the northern tip of the island of Newfoundland. See Leif Eriksson; Vikings; Vinland.

Lasting contact between Europe and America began with the voyage of Christopher Columbus in 1492. Columbus sailed west from Spain to find a short sea route to the Indies, as Europeans called eastern Asia. This region was known for its jewels, silks, spices, and other luxury goods. When Columbus landed in America, he thought he had reached the Indies, but he actually had landed on an island in the Caribbean Sea.

In 1497, King Henry VII of England hired an Italian navigator, John Cabot, to cross the Atlantic Ocean in search of a shorter route to Asia than the one Columbus had taken. No one knows exactly where Cabot landed. Most historians say he may have landed somewhere between what are now the island of Newfoundland and Nova Scotia. Cabot claimed the area for England. He found no such luxuries as jewels or spices. But he saw an enormous amount of cod and other fishes in the waters southeast of Newfoundland. Reports of the rich fishing soon brought large European fishing fleets to Canada.

By the early 1500’s, some Europeans realized that Columbus had reached an unknown land, which they called the New World. In 1534, King Francis I of France sent Jacques Cartier, a French navigator, to the New World to look for gold and other valuable metals. Cartier sailed into the Gulf of St. Lawrence. He landed on the Gaspé Peninsula and claimed it for France. In 1535, on a second trip, Cartier became the first European to reach the interior of Canada. He sailed up the St. Lawrence River to the site of present-day Montreal. In 1541, on a third visit, Cartier joined a French expedition that hoped to establish a permanent settlement in Canada. But the colony lasted only until 1543.

The development of New France (1604-1688)

Many French fishing crews sailed to Canada in the early 1500’s. They helped develop a thriving fishing industry off the east coast. But they played an even more important role in Canada’s growth by establishing the fur trade. The fur trade led to the development of a French colonial empire in North America. This empire, known as New France, lasted about 150 years and established the French culture and heritage in Canada (see New France).

Start of the fur trade.

The French fishermen who came to Canada landed on the coast to preserve their catches by drying them in the sun. They met First Nations people who wanted to trade furs for fishhooks, kettles, knives, and other European goods. A brisk trade soon developed. During the second half of the 1500’s, felt hats made from beaver fur became tremendously popular in Europe. As a result, the value of Canadian beaver pelts soared. During the late 1500’s, more and more French ships sailed to Canada to pick up beaver fur. Traders also supplied such furs as fox, marten, mink, and otter. See Fur trade.

Meanwhile, English explorers searched for a water passage to Asia through northern Canada. During the late 1500’s, these explorers included Humphrey Gilbert, Martin Frobisher, and John Davis. In 1610, an English sea captain named Henry Hudson sailed into Hudson Bay in his search for the passage. England later based its claim to the vast Hudson Bay region on this voyage.

Early settlements.

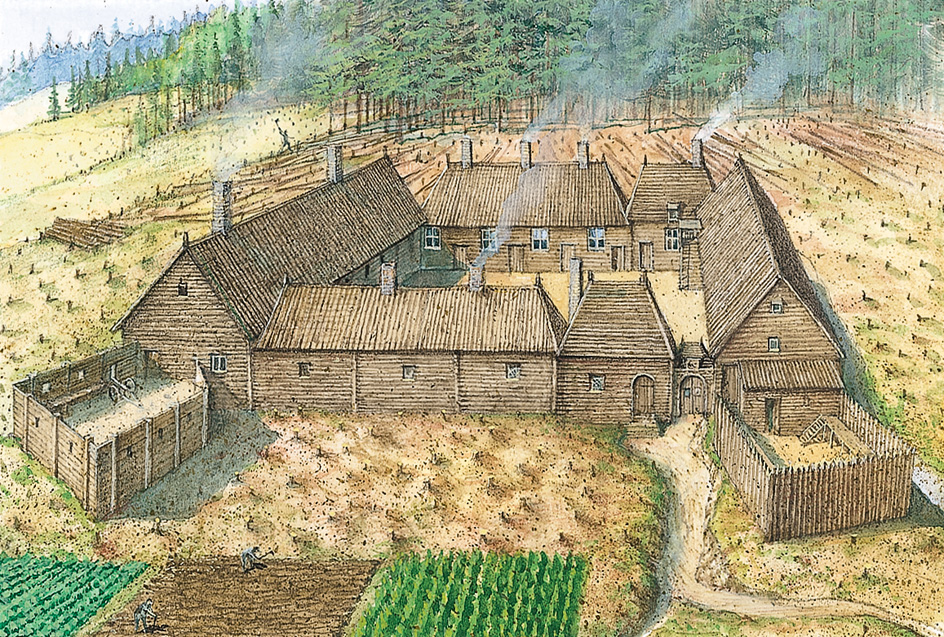

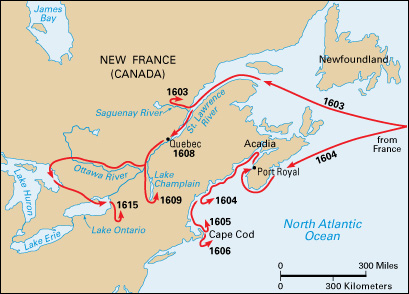

In 1603, King Henry IV of France completed plans to organize the fur trade and to set up a colony in Canada. The next year, a French explorer named Pierre du Gua (or du Guast), Sieur de Monts, led a small group of settlers to a site near the mouth of the St. Croix River. The river is on the border between what are now New Brunswick and Maine. In 1605, the settlers left that spot and founded Port-Royal (later moved to the site of Annapolis Royal in Nova Scotia). The French called their colony Acadia. See Acadia.

In 1608, another French explorer, Samuel de Champlain, founded a settlement along the St. Lawrence River. He named the village Quebec. Champlain made friends with the native Algonquin and Huron people living nearby and began to trade with them for furs. The Algonquin and Huron also wanted French help in wars against their main enemy, the powerful Iroquois, another Indigenous group. In 1609, Champlain and two other French fur traders helped the Algonquin and Huron defeat the Iroquois in battle. After this battle, the Iroquois were also enemies of the French.

The Huron lived in an area the French called Huronia. Champlain persuaded the Huron to allow Roman Catholic missionaries to work among them and introduce them to Christianity. The missionaries, especially an order known as the Jesuits, explored much of what is now southern Ontario.

Threats to expansion.

Champlain hoped Quebec would become a large settlement, but it remained only a small trading post for many years. By 1625, about 60 people lived there.

New France failed to attract settlers partly because of threats from English colonists as well as from the Iroquois. Like France, England claimed much of what is now eastern Canada. England based its claims on explorations dating from Cabot’s landing in 1497. During the early 1600’s, many English colonists settled along the east coast of North America south of New France. Numerous disputes over fur-trading rights broke out between the French and the English. In 1629, English forces captured the town of Quebec. The French regained the town in 1632. For the next 130 years, the French and English competed for control of New France.

During the late 1640’s, the Iroquois conquered Huronia and killed most of the French missionaries. The Algonquin and Huron fled, leaving the French to fight the Iroquois alone. During the next 10 years, the Iroquois increased their attacks on the French. Many settlers were killed, and the French fur trade was almost destroyed.

The royal province.

In 1663, King Louis XIV made New France a royal province (colony) of France. He sent troops to Canada to fight the Iroquois and appointed administrators to govern and develop the colony. The chief official was the governor. A bishop directed the church and missionary work, and a person called an intendant managed most other local affairs. The French troops mounted attacks on Iroquois country, forcing some Indigenous groups to make peace with the French in the late 1660’s. Afterward, frontiersmen known as coureurs de bois once again expanded the fur trade into the chief economic activity of New France (see Coureurs de bois).

Louis XIV also promoted the French seigneurial system to encourage farming in New France. Under this system, the king gave land in the colony to several groups, including French military officers and merchants. The landholders, called seigneurs, brought farmers from France and rented them large sections of the land. Most of the farmers, called habitants, became prosperous. They had large farms and significant freedom compared with habitants in France. The population of New France grew from about 3,000 in 1666 to about 6,700 in 1673. See Seigneurial system.

The boundaries of New France expanded rapidly to the west and south after Louis de Buade, Comte de Frontenac, became governor in 1672. The loss of the Huron fur trade forced the French to go farther inland to get new sources. As a result, Frontenac sent explorers to scout the Great Lakes and the Ohio and Mississippi river valleys.

In 1673, Louis Jolliet, a French-Canadian fur trader, and Jacques Marquette, a French missionary, sailed down the Mississippi River to its junction with the Arkansas River. The French soon built forts and fur-trading posts along the Great Lakes and along the Illinois and Mississippi rivers. In 1682, René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, reached the mouth of the Mississippi at the Gulf of Mexico. He claimed all the land drained by the river and its branches for France.

The growing French-English rivalry.

The boundaries of English colonies south of New France also expanded during the late 1600’s. Settlers poured into the English colonies and pushed the frontier westward, nearer New France. In 1670, an English firm called the Hudson’s Bay Company opened fur-trading posts north of New France on the shores of Hudson Bay.

Clashes between England and France in Europe contributed to their rivalry in North America. Other factors also created tension between the English and French colonists. For example, most of the French were Roman Catholics, and the majority of the English were Protestants. Most of the French wanted land for fur trading. The English wanted it for farming. In addition, French and English fur traders competed against each other.

During the 1730’s, French-Canadian fur traders traveled farther inland and claimed more land for France. By 1738, Pierre Gaultier de Varennes, Sieur de La Vérendrye, had established a chain of fur-trading posts between Montreal and what is now Saskatchewan.

British conquest and rule (1689-1815)

The French and English colonists fought each other in four wars between 1689 and 1763. These conflicts led to Britain’s conquest of New France. The British government then worked hard to win the support of its new French-Canadian subjects. During the late 1700’s and early 1800’s, Canadian explorers and fur traders pushed westward across the continent.

The colonial wars.

The first three of the four wars between the French and English broke out in Europe before spreading to America. These wars in America were King William’s War (1689-1697), Queen Anne’s War (1702-1713), and King George’s War (1744-1748). Only after the second war did either side gain territory. In 1713, under the Treaty of Utrecht, France gave Britain Newfoundland, the mainland Nova Scotia region of Acadia, and the Hudson Bay territory.

The fourth war first broke out in the Ohio River Valley in 1754 and lasted until 1763. It spread to Europe in 1756 and became known as the Seven Years’ War there and in Canada. The conflict, which is called the French and Indian War in the United States, marked the final chapter in the struggle between the French and British colonists in America. The British had a number of advantages during the war. For example, there were more than a million British colonists compared with about 65,000 French settlers. The British colonies also received greater military support from Britain than New France did from France. In addition, the British had the help of the Iroquois, the strongest Indigenous group in the east.

The French did well at first, but the tide of battle slowly turned against them. British armies, backed by the British Royal Navy, captured Quebec City in 1759. Both opposing generals, the Marquis de Montcalm of France and James Wolfe of Britain, were fatally wounded in the battle (see Quebec, Battle of). The British seized Montreal in 1760, and the fighting in America ended. In the Peace of Paris, signed in 1763, France surrendered most of New France to Britain. See French and Indian wars.

The Quebec Act.

Britain gave the name Quebec to the area that made up most of its new territory in Canada. It added some of the new territory to Nova Scotia and Newfoundland. At first, Britain governed Quebec under British laws, which denied Catholics the rights to vote, to be elected, or to hold public office. This policy affected nearly all the colony’s French Canadians. Quebec’s first two British governors, Generals James Murray and Guy Carleton, opposed the policy because they wanted Britain to gain the loyalty of the French. Carleton also was aware of discontent in the 13 colonies to the south, then known as the American Colonies. He knew that Britain would need the support of the French Canadians if an American rebellion broke out.

In 1774, Carleton persuaded the British Parliament to pass the Quebec Act. This act recognized French civil and religious rights. It also preserved the seigneurial landholding system and extended Quebec to include much of what is now Quebec, Ontario, and the Midwestern United States. The people in the American Colonies saw the act as an attempt to discourage them from moving westward. See Quebec Act.

The American Revolution began in 1775. The Americans asked the French Canadians to join their rebellion against Britain. But the French regarded the war mainly as a conflict between Britain and British colonies and largely chose to remain neutral. An American invasion of Canada in 1775 failed after French militia united with British soldiers and colonists to defeat the Americans at Quebec City. See American Revolution (The invasion of Canada).

The United Empire Loyalists.

After the American Revolution began, many people in the American Colonies remained loyal to Britain. About 40,000 of them moved to Canada during and after the war. These colonists became known as United Empire Loyalists. They settled mainly in western Nova Scotia and southeast of Montreal in Quebec. Those who moved to Nova Scotia soon demanded a colony of their own. In 1784, the British government created New Brunswick out of western Nova Scotia for the Loyalists.

The Loyalists in Quebec also became unhappy. The Quebec Act gave the Catholic Church a special position in the colony. But most Loyalists were Protestants. In addition, the act did not permit the colony to have its own elected legislature. The Loyalists in Quebec demanded a government like the one they had before the revolution—one that allowed them to chose their own public officials.

The British solution was the Constitutional Act of 1791. This act divided Quebec into two colonies, Lower Canada and Upper Canada. Lower Canada occupied the area along the lower St. Lawrence River. Upper Canada covered the area near the Great Lakes and the upper St. Lawrence. Each colony had its own elected assembly, though these legislatures had little real power. Each colony also had a lieutenant governor and a Legislative Council. The lieutenant governor and council members, who were appointed by the British, controlled the government. French Canadians formed the vast majority of the population in Lower Canada. The government there was based on principles of French civil law, Catholicism, and the seigneurial system. English-speaking Canadians made up the majority in Upper Canada. Local officials there followed the traditions of English law and property systems. See United Empire Loyalists.

Exploration of the West.

The American Revolution led to major developments in the Canadian fur trade. After Britain gained control of New France in 1763, hundreds of British merchants settled in Montreal and soon took over the French fur trade. Like the French, they obtained most of their furs from Indigenous people in the Ohio and Mississippi river valleys. But most of this area became part of the United States after the American Revolution. British merchants in Montreal thus had to look elsewhere for furs. By 1784, they had formed a firm called the North West Company to trade north and west of the Great Lakes. The Hudson’s Bay Company already had trading posts in that territory, and a great rivalry developed between the two companies.

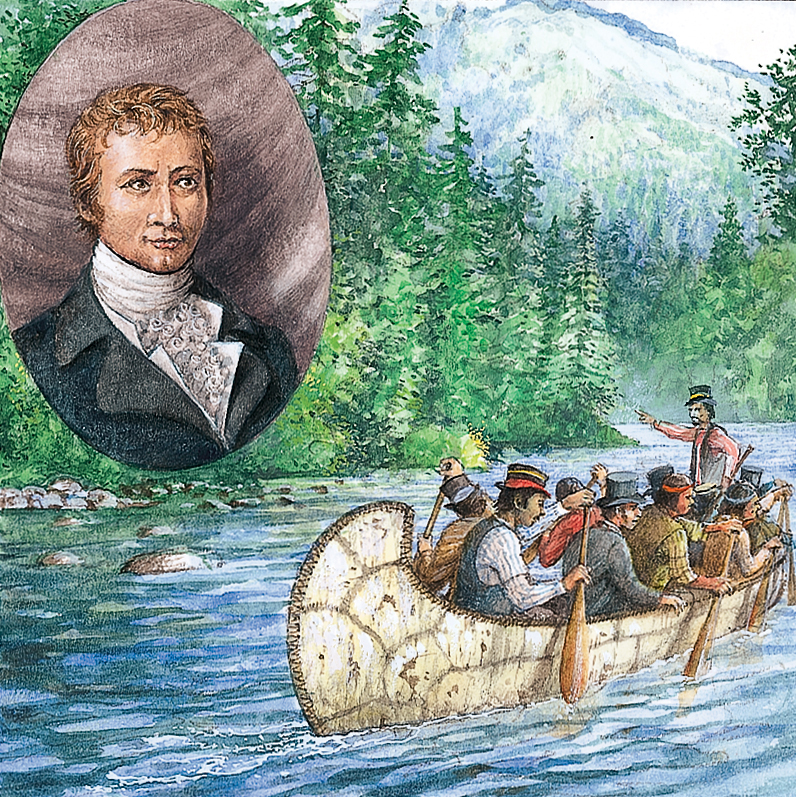

In its search for new and better fur-trading areas, the North West Company sent explorers across the unknown western lands. Alexander Mackenzie reached the Mackenzie River in 1789 and the Pacific Ocean in 1793. Simon Fraser followed the Fraser River to the Pacific in 1808. David Thompson mapped the west and navigated the full length of the Columbia River in 1811.

In 1811, Lord Selkirk, a Scottish colonizer, sent a group of Scottish and Irish immigrants to establish a settlement on the Red River in what is now Manitoba. The settlement became known as the Red River Colony. In 1821, the Hudson’s Bay Company took over the North West Company and gained control of nearly all Canadian territory west of the Great Lakes.

The War of 1812

developed out of fighting between Britain and France in Europe. During this conflict, the British set up a naval blockade of France and so interfered with U.S. ships bound for French ports. They also stopped American ships and seized sailors of British birth. In the United States, a group known as the war hawks wanted to seize control of Canada and British lands west of there. As a result of British actions, the United States declared war on Britain on June 18, 1812. American troops tried to capture Upper and Lower Canada during the war. But British troops, aided by Indigenous people allies and Canadian militia, defeated several invasion attempts. The war ended in 1815. The Canadian and British forces claimed victory because they had held off much larger American forces. Neither side actually won, but the war promoted a sense of unity and patriotism in Canada. See War of 1812.

Slavery in Canada

Slavery existed in what is now Canada before the French settled there in the early 1600’s. For hundreds of years, the First Nations that inhabited what are now Quebec and southern Ontario—chiefly the Huron and Iroquois—enslaved enemy warriors captured in battle. These enslaved Indigenous people performed all kinds of menial labor around the longhouses of their captors.

When French explorers, farmers, and fur traders began arriving in what is now eastern Canada in the early 1600’s, they brought some enslaved Africans with them. However, the majority of enslaved people in the area remained Indigenous. It has been estimated that by the 1750’s, about 1,400 out of 4,000 total enslaved people in the region were of African descent.

The absence of plantation agriculture and major manufacturing kept slavery from developing on a massive scale in Canada. The small farms of the seigneurial system did not create the same demand for slave labor as large plantations in the American Colonies to the south did. Some French settlers urged that New France develop a slave trade such as that in the French West Indies. But New France lay far from the center of the Atlantic slave trade that carried millions of Africans to the Caribbean region and the east coast of the American Colonies. Additionally, wars between the British and French in North America from the late 1600’s through the mid-1700’s interrupted efforts to establish a slave trade in what is now Canada.

France tried to regulate slavery in its colonies with the Code Noir (Black Code) of 1685. Far from a humanitarian document, it sought to govern relations between enslaved people and slaveholders. A modification of the Code Noir in 1724 insisted on the basic humanity of enslaved people. However, this ideal often was ignored.

Britain won control over New France in 1763, after the Seven Years’ War. When United Empire Loyalists began to move north at the start of the American Revolution (1775-1783), they were permitted to bring enslaved people with them. These enslaved people mainly performed household duties and worked in small businesses. However, a new law in 1793 banned the importing of enslaved people to the recently created colony of Upper Canada, where many Loyalists settled. The first such law in the British colonies, it was passed 14 years before the abolition of the slave trade in Britain itself in 1807. An 1833 act of the British Parliament abolished slavery throughout the British Empire. It took effect in 1834.

The struggle for responsible government (1816-1867)

Canada’s population began to soar during the early 1800’s as thousands of immigrants came from Britain. During the 1840’s, leaders in some Canadian colonies pushed for responsible government in local affairs. In a system of responsible government, the executive is responsible for its actions to a legislative body elected by the people. Britain gradually granted all the colonies such government. During the mid-1860’s, some colonial leaders argued that Canada needed a strong central government to deal with domestic matters. They started a movement for a confederation (union) of the Canadian colonies. This movement led to the formation of the Dominion of Canada in 1867.

Growing discontent.

After the War of 1812, Canada began to attract large numbers of immigrants from England, Ireland, and Scotland. French Canadians resented the flood of English-speaking newcomers into Lower Canada. Many of the French believed that the British government wanted to destroy the French heritage in Canada.

By the 1820’s, most French Canadians had become bitter toward the English-speaking Canadians in Lower Canada. The French controlled the legislature, but the English controlled the Legislative Council. The council, in turn, ran the government. It spent much of the colony’s tax money on projects to benefit commerce. French Canadians owned few businesses, however, and so opposed these expenses. The French also feared that the council intended to help English-speaking Canadians take over French-Canadian farms.

Upper Canada also faced serious political problems during the early 1800’s. Church leaders, merchants, and landowners there formed a group known as the Family Compact. This group controlled the colonial government. It often cooperated with the lieutenant governor to block the demands of the farmers in the assembly. The Family Compact also used tax money to support Church of England schools, though many Upper Canadians belonged to other religious groups.

The uprisings of 1837.

By the late 1830’s, many people in Upper and Lower Canada had lost faith in their colonial governments. In November 1837, a revolt broke out in Lower Canada. It was headed by Louis Joseph Papineau, a fiery French Canadian who was a leader in the assembly. Papineau’s followers briefly controlled parts of the countryside of Lower Canada. But the seigneurs and the high church officials remained loyal to Britain. British troops and colonial militia quickly crushed the revolt, and the rebel leaders fled to the United States.

News of the fighting in Lower Canada triggered a rebellion in Upper Canada in December 1837. William Lyon Mackenzie, a member of the Reform Party in the assembly, led the revolt. The colonial militia defeated the rebels in a brief battle, and Mackenzie escaped to the United States. See Rebellions of 1837.

Lord Durham’s report.

The rebellions in Upper and Lower Canada convinced the British government that it had serious problems in Canada. In 1838, Queen Victoria sent Lord Durham, a British diplomat, to investigate the causes of the uprisings. Durham finished his report in 1839. He recommended that Upper and Lower Canada be united. He also recommended that the Canadian colonies be allowed to handle their local affairs. Both of these ideas had been suggested earlier, and Durham’s report did little to influence their eventual adoption by the British government. In 1840, the British Parliament passed the Act of Union. This law, which took effect in 1841, united the two Canadas into one colony, the Province of Canada. See Union, Act of.

The beginning of self-government.

During the 1840’s, several colonial leaders fought for responsible government. These leaders included Robert Baldwin and Louis H. Lafontaine in the Province of Canada and Joseph Howe in Nova Scotia. Many officials in Britain had come to regard the colonies more as a financial burden than as a benefit, and they supported the self-government movement. The Province of Canada and Nova Scotia gained responsible government in 1848. The same year, the colony of New Brunswick gained almost complete control over its own affairs. Prince Edward Island gained responsible government in 1851, and Newfoundland gained it in 1855.

During the mid-1800’s, the Canadian colonies expanded trade with the United States. Railways linked more and more towns in the colonies, and new canals became busy transportation routes. These developments and the rapid growth of the fishing, flour-milling, lumber, and textile industries brought prosperity to the Canadian colonies. The American Civil War (1861-1865) also greatly increased demands for Canadian goods.

In spite of responsible government, political problems still troubled the Province of Canada. The main opposing political parties had nearly equal representation in the legislature. As a result, no party could gain a majority of seats or direct the government for long. By the early 1860’s, some political leaders had suggested that the colony’s problems could be solved only by splitting it again and creating a confederation of the two colonies. The union would give French- and English-speaking Canadians the same central government but would allow them to control their own local affairs.

Confederation.

The fear of United States expansion into Canada helped attract support for a Canadian confederation. Many Canadians felt certain that the United States wanted to control all North America and would invade Canada after the Civil War ended.

John A. Macdonald, George Étienne Cartier, and other leaders from the Province of Canada headed the campaign for a federal union. In September 1864, they attended a conference of leaders from the Atlantic colonies who were meeting in Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island, to plan a union of their own. The Canadians persuaded them to abandon their plan in favor of a larger union. As a result, another conference was held in Quebec City. The final details for confederation were worked out there in October (see Quebec Conference).

In 1865, the Province of Canada approved the confederation plan. However, Newfoundland and Prince Edward Island rejected it, fearing that they would lose control over local affairs. New Brunswick and Nova Scotia adopted the plan in 1866. Later that same year, officials from the Province of Canada, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia went to London, where they presented the plan to the British government.

In March 1867, the British Parliament passed the British North America Act. This act established the Dominion of Canada. The Dominion used the British parliamentary form of government. It had an elected House of Commons and an appointed Senate, each with almost equal power. A prime minister, usually the leader of the political party with the most seats in the House of Commons, headed the new federal government. Britain continued to handle the colony’s foreign affairs, and the British monarch served as head of state.

The British North America Act took effect on July 1, 1867. The new Dominion had four provinces—New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Ontario, and Quebec. Quebec had formerly been Lower Canada, and Ontario had been Upper Canada. The British North America Act provided that other provinces could join the Dominion. Macdonald, leader of the Liberal-Conservative Party, became the country’s first prime minister. See British North America Act; Confederation of Canada.

Growth of the Dominion (1868-1913)

The young Dominion of Canada developed rapidly during the late 1800’s. A railway connected western and eastern Canada, and courageous pioneers spread across the west. By the early 1900’s, the Dominion had nine provinces spanning the continent. Huge wheat crops, rich mines, and new industries brought further economic expansion in this period. In addition, Canada became increasingly involved in international affairs.

New provinces.

Macdonald’s chief goal as prime minister was to extend the Dominion to the west coast. He immediately turned his attention to the vast, largely unsettled northwest. This territory, called Rupert’s Land, was owned by the Hudson’s Bay Company. Macdonald worked out an agreement to buy the region in 1869.

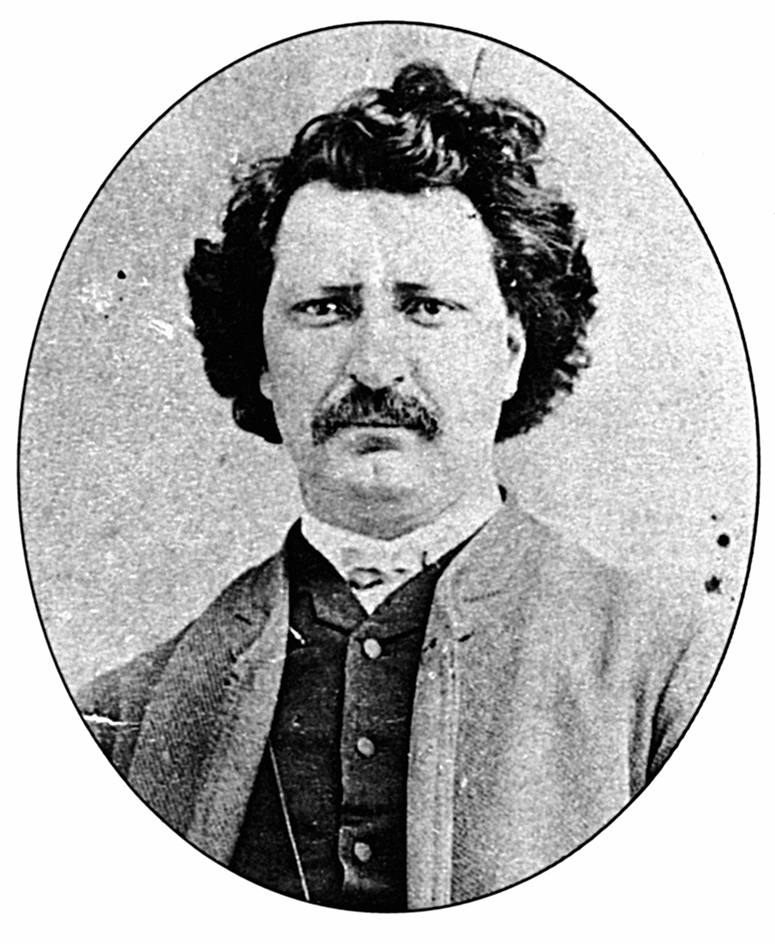

About 12,000 people lived in or near the settlement of Red River in Rupert’s Land. Most of them were Métis (people of mixed white and First Nations ancestry). The Métis feared that the transfer of the area to Canada would bring a flood of white settlers who would take their lands. In 1869, Louis Riel, a settler of French and First Nations descent, led the Métis in a revolt against the Canadian government. British troops and a small number of Canadian militia put down the rebellion (see Red River Rebellion).

In 1870, the government created Manitoba, Canada’s fifth province, from part of Rupert’s Land. The government set aside 1,400,000 acres (567,000 hectares) in Manitoba for the Métis. Also in 1870, the government established the North-West Territories from land acquired from the Hudson’s Bay Company.

In 1871, British Columbia, a British colony on North America’s Pacific coast, became Canada’s sixth province. It agreed to join the Dominion in return for construction of a railway to the Pacific coast within 20 years. In 1873, the eastern colony of Prince Edward Island became Canada’s seventh province.

The Pacific Scandal.

Macdonald led the Conservative Party to victory in the election of 1872. Afterward, the government chose a company headed by Sir Hugh Allan to build a railway to the Pacific coast. But in 1873 it came to light that the Conservative Party had accepted a campaign contribution of about $300,000 from Allan in 1872. Leaders of the opposing Liberal Party charged that Allan’s group got the railroad contract because of its campaign gift. Macdonald resigned as prime minister. In November 1873, Alexander Mackenzie, leader of the Liberal Party, became prime minister.

The return of Macdonald.

Mackenzie’s government promoted honest and efficient elections by introducing the secret ballot and the one-day national election. It also enacted a policy limiting the authority of the governor general—the British monarch’s representative in Canada—and established the Supreme Court of Canada. But the government became increasingly unpopular after 1875, when a worldwide depression caused a severe business slump in Canada. Mackenzie had little success in reversing the decline, and Macdonald led the Conservatives to victory in the election of 1878.

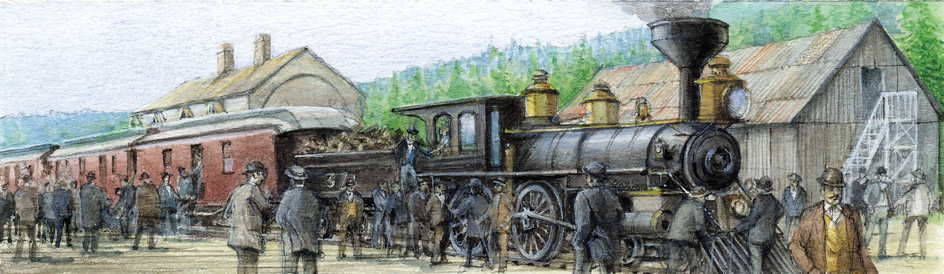

In 1879, Macdonald began the National Policy, which called for high tariffs (taxes) on imported goods. The program was designed to stimulate Canada’s industries. It raised the cost of foreign products compared with Canadian products. Macdonald was also determined to complete the stalled coast-to-coast railroad. In 1880, the government gave the new Canadian Pacific Railway Company a contract to finish the job.

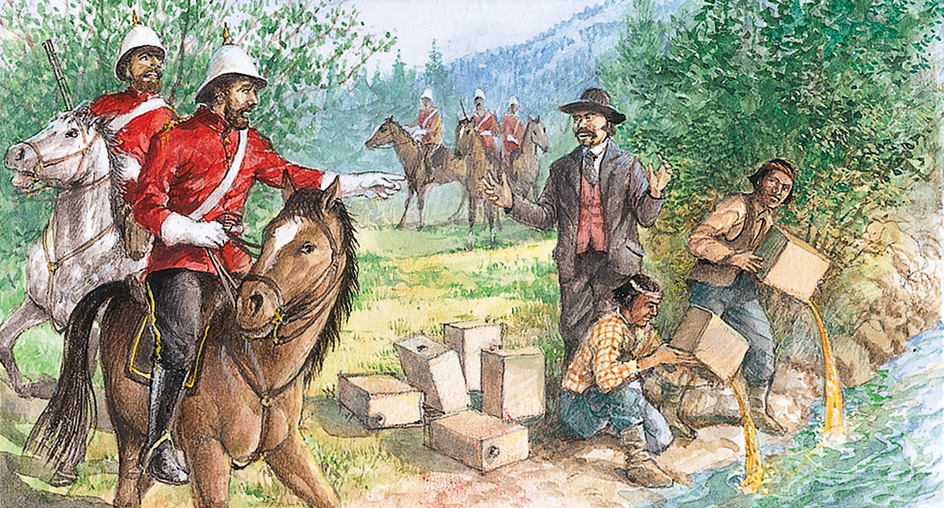

The North West Rebellion.

During the 1870’s, many of the Métis in Manitoba moved westward into what is now Saskatchewan. But they again began to fear the loss of their land during the mid-1880’s because of the near completion of the transcontinental railroad and government plans to attract settlers to the prairies.

In March 1885, Riel led another Métis uprising, the North West Rebellion. More than 7,000 government troops ended the rebellion within three months. Riel was found guilty of treason and was hanged on Nov. 16, 1885. See North West Rebellion.

Progress under Laurier.

Workers laid the final stretch of Canadian Pacific Railway tracks in 1885. Regularly scheduled passenger service began the next year. The transcontinental railroad in time led to a great rush to settle Canada’s fertile western prairies. This activity contributed to a major period of progress that began after the Liberal Party won the election of 1896. Wilfrid Laurier, the Liberal Party leader and a Catholic from Quebec, became Canada’s first French-Canadian prime minister.

Canada’s population soared during Laurier’s administration. More than 2 million immigrants, most of them from Europe, flocked to Canada between 1896 and 1911. Many settled in such cities as Montreal, Toronto, and Winnipeg. But hundreds of thousands of others took up farming on the prairies. In 1905, the government created two new provinces out of the prairies, Alberta and Saskatchewan.

Canada’s economy flourished under Laurier. Farmers in the Prairie Provinces produced huge wheat harvests, and Europe became a great market for Canadian wheat. Aided by the continuing high tariffs, Canada’s flour-milling, steel, and textile industries grew quickly. Nova Scotia coal mines thrived, and mining areas opened or expanded in Ontario, British Columbia, and the Klondike region of northern Canada. New hydroelectric power plants and two new transcontinental railroads, the Grand Trunk Pacific and the Canadian Northern, helped make the early 1900’s Canada’s most prosperous period since 1867.

Foreign relations.

Canada’s role in the British Empire became an issue when the Anglo-Boer War of 1899-1902 broke out between the British and the Boers in southern Africa. Many Canadians had great pride in the empire and wanted Canada to send troops to help the British forces. But a large number of French Canadians opposed Canada’s participation in foreign wars. Laurier compromised by organizing, equipping, and transporting two contingents of volunteers, who were paid mainly by Britain after they reached South Africa.

In 1910, a controversy developed over a proposed trade agreement between Canada and the United States. The agreement allowed each country to export agricultural products and natural resources to the other without paying high tariffs. But many Canadian business leaders feared the trade agreement would promote American imports into Canada, and they opposed it.

A dispute involving Canada’s obligations to the empire arose in 1910. Britain faced the threat of war with Germany and asked Canada to supply ships and sailors for the British Royal Navy. Laurier responded by announcing a plan to build a separate Canadian navy that could be lent to Britain in time of war. But English-speaking Canadians insisted that Canada contribute directly to the Royal Navy. Many French Canadians also opposed Laurier’s plan, charging that it would involve Canada in foreign wars.

Opposition to the trade agreement and the naval plan led to the defeat of Laurier’s party in the election of 1911. Robert L. Borden, head of the victorious Conservative Party, became prime minister.

World War I and independence (1914-1931)

Canada entered World War I (1914-1918) to aid Britain and its allies. Canada’s participation in the war enabled it to act more freely in establishing its own foreign policies. In 1931, the Dominion won complete independence from Britain.

World War I.

Britain’s declaration of war on Germany on Aug. 4, 1914, created a tremendous burst of patriotism in Canada. Thousands of Canadians rushed to volunteer for military duty. Canadian troops first saw combat in April 1915. They helped halt the first German gas attack of the war during the Second Battle of Ypres in Belgium. The greatest Canadian triumph came in the Battle of Vimy Ridge in France on April 9, 1917. In the battle, about 100,000 Canadian troops captured the strong German positions on a hill called Vimy Ridge (see Vimy Ridge, Battle of). Billy Bishop, a Canadian flier, shot down 72 German planes during the war and became one of its most famous combat pilots (see Bishop, Billy). Over 600,000 Canadians served in the armed forces during World War I, and about 60,000 died.

World War I contributed enormously to Canada’s industrial strength. The country’s steel industry thrived through the sale of ships, artillery shells, and other equipment to Britain. Wartime demand also greatly expanded agricultural output, especially the production of beef cattle and wheat.

The conscription issue.

When World War I began, Borden promised that Canada would not conscript (draft) men for overseas military service. He knew that French Canadians bitterly opposed conscription. Early in the war, large numbers of volunteers made a draft needless. By early 1917, however, Canadian forces had suffered high casualties, and the number of volunteers had dropped sharply. As a result, Borden established conscription in July 1917. He received strong support from English-speaking Canadians, but French Canadians strongly objected.

To make conscription work, Borden decided to form a coalition (joint) Conservative-Liberal government, which he called the Union government. Borden tried to bring Wilfrid Laurier and other Liberal Party leaders into the coalition. But Laurier opposed conscription and refused to join. The Liberals then split into two groups. One group, the Unionist Liberals, backed conscription. The other group remained loyal to Laurier. Borden appointed a number of Unionist Liberals to his government and called for an election in December 1917. The Unionists won every province except Quebec.

A larger role in the empire’s affairs.

Borden became increasingly dissatisfied with Canada’s colonial status in view of its major contribution to the British war effort. In 1917, Borden and the leaders of other dominions in the British Empire began to demand greater participation in developing foreign and defense policies. The British needed soldiers and weapons from the dominions and so agreed to their demands.

After World War I, Borden and the other dominion prime ministers were members of the British Empire’s peace delegation in Paris in 1919. They signed the Treaty of Versailles, which officially ended the war with Germany. In addition, all the dominions became original members of the League of Nations, an international association formed in 1920 to maintain the peace.

Labor and farm unrest.

While Borden attended the peace conference in Paris, trouble mounted at home. Workers throughout Canada demanded higher wages, better working conditions, and recognition of their unions. Farmers wanted relief from low crop prices and urged reductions in railway freight rates. Dissatisfied farmers formed political parties in almost every province. Farmer parties won control of the provincial government in Ontario in 1919 and in Alberta in 1921. In the national election of 1921, the Liberal Party gained a plurality of seats—that is, more seats than any other party—in the House of Commons. William Lyon Mackenzie King became prime minister.

In 1921, Agnes Macphail became the first woman to serve in the Canadian House of Commons. She was elected to represent the United Farmers of Ontario.

Independence.

King was determined to establish Canada’s independence in foreign affairs. In 1922, he refused to support Britain in a possible war with Turkey and rejected a request for Canadian troops. On King’s insistence, Canada for the first time signed a treaty alone with another nation in 1923. The treaty, with the United States, regulated halibut fishing in the Pacific Ocean.

In 1926, King and representatives from the other dominions met with British representatives at an Imperial Conference in London. There, dominion and British representatives declared the dominions to be independent members of the British Commonwealth of Nations, as the British Empire then became known. In 1931, the British Parliament passed the Statute of Westminster, which legalized the declaration. This act officially recognized Canada and the other self-governing dominions as independent nations.

The young nation (1932-1957)

During the 1930’s, the young Canadian nation suffered through the Great Depression. The hard economic times ended when production rose during World War II (1939-1945). After the war, an industrial boom at home helped make Canada a major economic power. The nation also became greatly involved in world affairs.

The Great Depression

began in 1929 with the stock market crash in the United States and spread throughout the world. The depression caused a sharp drop in foreign trade and especially hurt the demand for Canadian food products, lumber, and minerals. The decline in export income forced thousands of Canadian factories and stores, plus many coal mines, to close. Hundreds of thousands of Canadians lost their jobs and homes. A rapid fall in grain prices and a severe drought worsened the depression in the Prairie Provinces.

Unemployment was the chief issue in the election of 1930. King’s government was defeated, and the Conservatives came to power under Richard B. Bennett. Bennett’s government established more than 200 relief camps for single, unemployed men and spent hundreds of millions of dollars to aid the needy.

Bennett dealt harshly with strikers and demonstrators and earned the nickname “Iron Heel Bennett.” But he also saw the need for reform. His government created a number of important federal agencies, including the Canadian Radio Broadcasting Commission in 1932, the Bank of Canada in 1934, and the Canadian Wheat Board in 1935. Canada’s economic problems continued, however, and many Canadians blamed Bennett for failing to ease the hard times. Bennett’s unpopularity led to the formation of new political parties, which included the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation in 1932 and the Social Credit Party in 1935. In the election of 1935, the Liberal Party regained control of the House of Commons. King then began his third term as prime minister. See Great Depression (Effects in Canada).

World War II.

Canada declared war on Germany on Sept. 10, 1939. It declared war on Japan on Dec. 8, 1941, the day after Japan attacked United States bases at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii. The Canadian Army first saw action in December 1941, when it participated in the unsuccessful attempt to defend Hong Kong against a Japanese invasion. In August 1942, the Army suffered heavy losses in the Allied assault on the French port of Dieppe.

Canadian troops also took part in the Allied invasion of Sicily in 1943 and in the battle for Italy. The Third Canadian Division participated in the Allied landing at Normandy in France on June 6, 1944. The First Canadian Army, commanded by General H. D. G. Crerar, fought its way through the Netherlands and advanced into northern Germany. The Royal Canadian Air Force aided the Allies, and the Canadian Navy helped protect Allied ships in the Atlantic Ocean. By the end of the war, more than a million Canadian men and women had served in the armed forces. More than 90,000 had been killed or wounded.

The Canadian government lent billions of dollars to the war cause. It sent the British people large quantities of food. Canadian factories built thousands of planes, ships, trucks, and weapons.

When World War II began, King pledged to keep recruiting for overseas service voluntary. In 1942, however, the government asked Canadian voters to release it from a pledge not to send draftees abroad. The vast majority of voters approved the request, though many French Canadians opposed it. No Canadian draftees went overseas until November 1944.

The war was especially tragic for Canadians of Japanese descent and for newly arrived immigrants from Japan. Japanese Canadians came under widespread distrust after Japan attacked Pearl Harbor. In February 1942, the Canadian government uprooted them from Pacific coastal areas and placed about 21,000 of them in camps and isolated towns in Alberta, British Columbia, Manitoba, and Ontario. Their rights were not restored until 1949. Most of the Japanese Canadians lost their homes and businesses.

The government adopted several important social programs during the war. It established the beginning of a social security system by introducing unemployment insurance in 1940. In 1944, it adopted a program that assisted families by providing financial aid for children. As the war came to an end, the government began a vast benefits program to help veterans return to civilian life.

The postwar boom.

Canada’s economy thrived after World War II. Canadians spent their wartime savings on appliances and other household goods. A great demand for housing created a construction boom. The development of Canada’s incredibly rich mineral deposits also flourished. The country became an important producer of asbestos, copper, iron ore, nickel, oil, uranium, and other minerals. Foreign investors, mainly from the United States, helped finance the development of many new industries. By the late 1950’s, Canada had changed from a chiefly agricultural country to one of the world’s great industrial nations.

Meanwhile, Canada experienced another great wave of immigration. From 1945 to 1956, more than a million people from Germany, Italy, and other war-torn European countries moved to Canada. Many of the immigrants settled in Toronto, Montreal, and other large cities. Suburbs grew rapidly outside the central cities.

Increasing foreign involvement.

King retired as prime minister in November 1948. Louis St. Laurent, the new Liberal Party leader, became Canada’s second French-Canadian prime minister. One of the first highlights of his administration occurred in March 1949, when Newfoundland (now Newfoundland and Labrador) became Canada’s 10th province. Under St. Laurent, Canada played an ever-larger role in international affairs.

Canada’s prestige and economic strength after World War II convinced many Canadians that their nation’s interests required active involvement in foreign affairs. In 1945, Canada became an original member of the United Nations (UN). In 1949, it signed a treaty with the United States and 10 Western European nations that set up the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). NATO was the first military alliance Canada had joined in peacetime.

During the Korean War (1950-1953), Canada contributed about 22,000 soldiers to the UN forces fighting North Korea’s invasion of South Korea. Canadians killed in action or on active duty in Korea totaled 516. Canada helped bring about stability in the Middle East after Britain, France, and Israel invaded Egypt in 1956. Lester B. Pearson, Canada’s secretary of state for external affairs, won the 1957 Nobel Peace Prize for proposing and organizing a UN peacekeeping force to patrol the troubled area between Israel and Egypt.

The end of Liberal rule.

Canadians were stunned in 1956, when the government broke the rules of Parliament to push through a bill to finance construction of a natural gas pipeline. John G. Diefenbaker, leader of the Progressive Conservative Party, charged that St. Laurent’s government had abused its authority and insulted Parliament. Many voters agreed. In the election of 1957, Diefenbaker led his party to a narrow victory and ended 22 years of Liberal rule.

Challenges of the 1960’s

Major economic and social problems troubled Canada in the 1960’s. A business slump struck the country, and unemployment rose sharply. French Canadians began a movement to increase their political power. In Quebec, many French Canadians began to support a campaign to make their province a separate nation.

The new Conservative government.

Diefenbaker hoped to broaden his support in Parliament and called an election in 1958. The Progressive Conservatives won 208 of the 265 seats in the House of Commons, the largest majority in Canadian history. In 1959, Diefenbaker joined Queen Elizabeth II of Britain and U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower at the opening of the St. Lawrence Seaway. The seaway enables large commercial ships to sail between the Atlantic Ocean and the Great Lakes by way of the St. Lawrence River.

In 1960, a sagging economy challenged the Diefenbaker government. By 1961, 11 percent of Canadian workers had no jobs. The government responded by trying to increase foreign trade. It developed new markets for Canadian wheat in China and the Communist countries of Eastern Europe. In 1962, during an election campaign, the government attempted to boost the economy by lowering the value of the Canadian dollar. In the June election, the Conservatives won the most seats in the House of Commons but not a majority. The Diefenbaker government was able to stay in power only with the aid of the Social Credit Party, which had won 30 seats.

The Quebec separatist movement.

Diefenbaker also faced rising discontent in Quebec. In 1960, the Quebec Liberal Party gained control of the provincial government. Led by Jean Lesage, the new government started the Quiet Revolution, a movement to defend French-Canadian rights throughout the country. Many French Canadians believed they were barred from jobs in government and some large corporations because they spoke French. They wanted English Canadians to recognize and respect Quebec’s French heritage. Lesage also worked to increase Quebec’s control over its own economy and to reduce such control by the federal government.

The Quiet Revolution awakened deep feelings of French-Canadian nationalism. In Quebec, it influenced the rise of separatism, the demand that the province separate from Canada and become an independent nation. In the early 1960’s, several separatist groups entered candidates in provincial elections. Other groups, especially the Front de Libération du Québec (FLQ), used terrorism to promote separatism. In 1963, the FLQ began to bomb federal buildings and symbols of Canada that reflected the country’s British traditions.

The return of the Liberals.

In 1959, Canada’s government purchased American-made Bomarc antiaircraft missiles for its defense. Early in 1963, a controversy developed over whether Canada had agreed in 1959 to accept nuclear warheads from the United States for its Bomarc missiles. The missiles were effective only with such warheads. Prime Minister Diefenbaker refused to accept the warheads because some members of his Cabinet opposed the use of nuclear arms. The Liberals in Parliament argued that Canada had agreed to take the warheads for use in the defense of North America. Lester B. Pearson, the Liberal leader, accused the government of breaking promises to the United States. In February, the House of Commons gave Diefenbaker’s government a vote of no confidence over the issue. Diefenbaker was then forced to call a national election.

In the election of 1963, the Liberals won the most seats in the House but not a majority. Pearson became prime minister with support from several small opposition parties. His government accepted the nuclear warheads. It also expanded social welfare programs, introducing a national pension plan in 1964 and a national health insurance program in 1965.

Pearson achieved a personal goal when Canada adopted a new national flag. The country had long used the British Red Ensign with a coat of arms representing Canada’s provinces. The Conservatives wanted to keep the Red Ensign as a symbol of Canada’s British heritage. But in 1964, Parliament approved a design that featured a red maple leaf, a symbol of Canada. On Feb. 15, 1965, Canada’s new flag flew for the first time.

Canada marked the 100th anniversary of Confederation in 1967 with national celebrations. A highlight was Expo 67, a world’s fair held in Montreal.

In April 1968, Pearson resigned as prime minister. His successor, Pierre Elliott Trudeau, became Canada’s third French-Canadian prime minister. Trudeau called a national election for June 25. The campaign was marked by widespread enthusiasm that became known as “Trudeaumania.” Canadians seemed to be madly in love with Trudeau, a dashing 48-year-old bachelor, and gave his party a majority of the seats in the House.

Canada under Pierre Trudeau

Trudeau served as Canada’s prime minister almost continuously from 1968 to 1984. Under Trudeau, Canada initially had high hopes for economic expansion. But sharply rising prices and high unemployment and interest rates caused problems. The Quebec separatist movement still threatened Canadian national unity. Canada also revised its constitution during this period.

Foreign affairs.

During the early 1970’s, Canada broadened its relations with the two leading Communist nations, China and the Soviet Union. In 1970, Canada and China agreed to resume diplomatic relations, which had ended when the Communists gained control of China in 1949. In 1971, Trudeau and Soviet Premier Aleksei N. Kosygin exchanged visits. Canada increased trade with both China and the Soviet Union.

Relations between the Canadian and U.S. governments, however, became increasingly strained during the 1970’s. The U.S. government disapproved of Canada’s willingness to accept American men who crossed the border to avoid being drafted in the Vietnam War (1957-1975). The United States also objected to new policies that limited foreign ownership and financing of Canadian industries.

Canadians, in turn, became disturbed by threats to their environment from the United States, especially the polluting of Canadian lakes and rivers by acid rain. The rain was a result of chemicals released into the air by U.S. factories and power plants. Control of fishing waters and other offshore resources in the northeast Pacific and northwest Atlantic also became an issue between Canada and the United States.

The separatist threat.

To curb the Quebec separatist movement, Trudeau pledged to create equal opportunities for French- and English-speaking Canadians throughout the nation. His first important move toward this goal was winning Parliament’s approval of the Official Languages Act in 1969. This act requires federal facilities to provide service in French in areas where at least 10 percent of the people speak French. It also requires service in English in areas where at least 10 percent of the people speak that language. The law brought major changes to the government. However, it had little effect on the growing separatist movement.

Canada experienced one of its most serious political crises in October 1970, when the FLQ kidnapped two officials in Montreal. The officials were James R. Cross, the British trade commissioner in Montreal; and Pierre Laporte, Quebec’s labor minister. The terrorists offered to exchange the two men for $500,000 and the release of 23 jailed FLQ members.

Trudeau rejected the offer. Instead, he put Canada’s War Measures Act into effect. This act allows the government to suspend the civil liberties of people judged dangerous during wartime. The law had never been applied during peacetime. Police used the act to arrest hundreds of FLQ sympathizers during their search for the kidnapped officials. FLQ members murdered Laporte. They released Cross in December, when the government permitted the kidnappers to go to Cuba.

FLQ terrorism ended, but the separatist movement continued. The Parti Québécois, organized as a separatist political party in 1968, won control of the government of Quebec in 1976. René Lévesque, a member of the Quebec legislature and the party’s leader, became premier of the province. In 1980, Lévesque’s government held a provincewide vote on a proposal to give provincial leaders authority to negotiate with the Canadian federal government for independence. About 60 percent of Quebec’s voters rejected the proposal.

Economic troubles.

An economic recession and rapid inflation developed in the mid-1970’s. Trudeau’s popularity also began to decline at that time. The Liberals lost the election of 1979 to the Progressive Conservatives, and Joe Clark became prime minister. Later that year, Clark announced a plan to conserve energy by raising fuel taxes. But strong opposition to the plan led the House of Commons to give the government a vote of no confidence. Clark then called an election for February 1980. The Liberals won a majority in the House, and Trudeau returned as prime minister.

Another recession struck Canada in the early 1980’s. By March 1983, 14 percent of workers had no jobs—the highest unemployment rate since the Great Depression.

Constitutional changes.

In 1981, Trudeau won acceptance of proposed changes in Canada’s constitution from all provincial heads except Levesque. The proposals became part of the Constitution Act of 1982, which the British Parliament passed in March.

The Constitution Act eliminated the need for British approval of Canadian constitutional amendments. The act also included a new bill of rights called the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms (see Bill of rights (Canada’s Constitution)). The revised constitution took effect on April 17, 1982. It replaced the British North America Act as the basic governing document of Canada.

Trudeau resigned in June 1984 and was succeeded by John N. Turner. The Progressive Conservatives, led by Brian Mulroney, won a national election in September 1984. Mulroney succeeded Turner as prime minister.

Canada under Brian Mulroney

Foreign affairs.

In 1988, Mulroney and U.S. President Ronald Reagan signed a major free-trade agreement. The agreement called for elimination of all tariffs and many nontariff trade barriers between the two countries by 1999. It went into effect on Jan. 1, 1989.

During the early 1990’s, Canada negotiated the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) with the United States and Mexico. This agreement took effect in 1994 and gradually eliminated tariffs and certain other trade barriers between the three countries.

In military affairs, the Canadian Armed Forces took part in the Persian Gulf War of 1991. Canadian pilots flew bombing missions over Iraq and Kuwait from their station in Qatar, a country near Saudi Arabia. It was the first time Canadian forces had been at war since the Korean War ended in 1953.

The constitutional crisis.

Hopes of winning Quebec’s acceptance of the constitution grew in 1987. That year, Mulroney and the 10 provincial heads of government tentatively agreed to a far-reaching constitutional amendment at Meech Lake, Quebec, on April 30. They formally approved the accord in Ottawa on June 3.

A key proposal in the agreement stated that Quebec was to be recognized as a distinct society in Canada. Also, each province could refuse participation in a wide range of new national programs and veto any future constitutional amendments that would involve federal institutions and the formation of new provinces.

To go into effect, the Meech Lake Accord had to be ratified by all 10 provinces by June 23, 1990. It was ratified by only eight. Manitoba and Newfoundland withheld their support. Many opponents of the accord believed that it granted Quebec’s provincial government too much power, especially over the rights of Quebec’s English-speaking minority. After the failure of the accord, many Quebecers began to demand increased independence for Quebec from the rest of Canada.

In August 1992, Canada’s 10 provincial heads of government agreed in Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island, to a new plan to revise the constitution. The plan provided for recognition of Quebec as a distinct society, the replacement of Canada’s appointed Senate with an elected one, self-government for Canada’s native peoples, and the transfer of some federal powers to the provinces.

Mulroney called for a nationwide vote on the Charlottetown accord. The referendum was held in October, and most Canadians, including a majority in Quebec, voted against it.

The 1993 national election.

Mulroney resigned in June 1993 and was succeeded by Kim Campbell. In October of that year, Jean Chrétien led the Liberal Party to victory in a national election. He became prime minister in November. Mulroney’s Progressive Conservative Party suffered one of the worst defeats in Canadian history, losing all but 2 of its 154 seats. Two regional parties became the second and third most powerful parties in the House. One of them, the Bloc Québécois, favors sovereignty for Quebec. The other, the Reform Party, was an Alberta-based conservative party.

Canada under Jean Chrétien

National unity.

In 1994, the separatist Parti Québécois regained control of Quebec’s government. In 1995, Quebec voters narrowly defeated a referendum calling for Quebec’s independence. In 1995 and 1996, Parliament passed two resolutions to promote national unity. One recognized Quebec’s unique language, culture, and civil law. The other granted five regions—Quebec, the Atlantic Provinces, Ontario, the Prairie Provinces, and British Columbia—what amounted to a veto over constitutional changes.

National elections.

The Liberals won national elections, often called federal general elections, in 1997 and 2000, largely because of a split between two conservative opposition parties. Chrétien remained prime minister. The Reform Party placed second in the 1997 election. In 2000, it joined the new Canadian Alliance party, which was created to unite Canadian conservatives. The Alliance placed second in the 2000 election.

Territorial and provincial changes.

In 1999, a new territory called Nunavut was carved out of the eastern Northwest Territories. Nunavut’s creation provided more self-government for the Inuit, who make up most of the area’s population. In 2001, Canada’s Parliament changed the official name of the province of Newfoundland to Newfoundland and Labrador.

The early 2000’s

Canada under Paul Martin.

Jean Chrétien stepped down as Liberal Party leader and prime minister in 2003. At that time, a number of scandals had become associated with him. Former finance minister Paul Martin succeeded Chrétien in both posts.

Also in 2003, Canada’s Progressive Conservative Party and the Canadian Alliance merged to form the Conservative Party of Canada. The new party became the official opposition in the House of Commons.

Prime Minister Martin called for a national election in 2004. As a result of the election, Martin’s Liberal Party formed a minority government, and Martin remained prime minister. In a minority government, the ruling party holds the most, but not a majority of, seats in the House of Commons. The Conservatives, led by Stephen Harper, placed second in the election and became the official opposition party.

In 2005, a commission of inquiry found that Chrétien’s Liberal government had misused public funds as part of a program to promote national unity in the late 1990’s and early 2000’s. The opposition parties in the House then passed a vote of no confidence in the government. Martin was forced to dissolve Parliament and call for a new election.

Canada under Stephen Harper.

The Conservatives, led by Stephen Harper, won a national election in 2006. Harper became prime minister of a minority government. Also in 2006, the House passed a motion to recognize “that the Québécois form a nation within a united Canada.” The motion acknowledged Quebec’s unique French cultural heritage.

In 2008, Prime Minister Harper publicly apologized to Canada’s Indigenous peoples for wrongs done to them by the country’s former residential school system. In the 1800’s and 1900’s, thousands of Indigenous children were forced to attend boarding schools created to integrate (incorporate) them into mainstream society. Abuse and neglect often occurred at these schools.

Twenty-four Canadians died in the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks in the United States. More than 40,000 Canadians served in the Afghanistan War (2001-2021), in which the United States and its allies battled the militant Islamic Taliban group. The combat role of Canadian troops ended in 2011. Canadian casualties included nearly 160 soldiers killed in action or on active duty.

An October 2008 national election resulted in another minority Conservative government led by Stephen Harper. Twice between December 2008 and March 2010, Governor General Michaëlle Jean suspended the work of Parliament at Prime Minister Harper’s request. The first time, the government faced a no-confidence vote in the House of Commons over financial issues. Such a vote could have brought down the government. The second time, officials said the government needed a break to focus on the economy. But critics claimed the government requested the suspension for political gain.

In March 2011, a legislative committee found the Harper government in contempt of (willfully disobedient to) Parliament. The committee said the government had failed to provide accurate information about the cost of crime legislation and military equipment. It was the first time a Canadian government was found in contempt. The Conservatives lost the support of the House, and Harper adjourned Parliament. A May 2011 election resulted in a majority Conservative government. Harper remained prime minister. The New Democratic Party placed second and became the official opposition party for the first time.

Canada under Justin Trudeau.

In 2015, the Liberals won a national election with a majority. Justin Trudeau, the son of Pierre Elliott Trudeau, became prime minister. Justin’s family fame, youth, and good looks helped attract international attention to Canada. He was the first Canadian prime minister who also was the child of a former prime minister. In addition, he was the first to appoint a Cabinet in which half the members were women. Gender equality became a significant feature of his government.

The new Liberal government had an ambitious agenda that included mending relations with Canada’s Indigenous people, many of whom had suffered because of government policies. For example, the new government created a National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls. The government also took actions to help the middle class, combat global warming, and reform democratic institutions. It raised taxes on the wealthiest Canadians and provided monthly payments to parents with young children. It limited the transport of fossil fuels and imposed a nationwide carbon tax (price on greenhouse gas emissions). The government also created an independent advisory board to recommend new candidates for the Senate. More controversially, it legalized medically assisted death for some patients, as well as recreational marijuana.

The Liberals, led by Trudeau, won the 2019 national election with the most, but not a majority of, seats in the House of Commons. They formed a minority government.

Canada, Mexico, and the United States renegotiated the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in the late 2010’s. An updated version of NAFTA took effect in 2020. In Canada, it was called the Canada-United States-Mexico Agreement (CUSMA). It maintained the largely tariff-free trade zone established by NAFTA, and introduced new obligations covering such areas as e-commerce, the environment, and labor practices.

Beginning in 2020, a global outbreak of COVID-19 greatly impacted Canada’s public health, as well as its economy. COVID-19 is a respiratory disease caused by a coronavirus. National and local efforts to stop the disease from spreading included restricting many public activities and, eventually, vaccinating most of the population. Nevertheless, as of early 2023, more than 4.5 million people in Canada had been infected, and more than 50,000 had died from the disease. Among the provinces and territories, Ontario and Quebec experienced the most infections and deaths.

Trudeau called for a national election to be held in 2021, two years earlier than required. At the time, the Liberals appeared to be in a good position to win a majority in the House of Commons. However, they won the election with a minority following a close race with the Conservatives.

Queen Elizabeth II of the United Kingdom, Canada’s official head of state, died in 2022. She had reigned since 1952. Elizabeth’s eldest son then became King Charles III and Canada’s head of state.