Rosetta was the first space probe to orbit a comet. The European Space Agency (ESA) launched Rosetta on March 2, 2004. Rosetta orbited comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko from August 2014 to September 2016. Scientists think that comets preserve dust, ice, and rock from the solar system’s formation. By gathering data on a comet, therefore, Rosetta helped scientists to learn more about the solar system’s composition and history. Rosetta was named for the Rosetta stone, a carved rock that enabled scholars to interpret ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs.

Rosetta studied 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko as the comet approached and closely circled the sun. It took 10 years of flight to position the probe next to the comet. During this time, Rosetta flew as far from the sun as 492 million miles (792 million kilometers), about the same distance as the orbit of Jupiter. The craft also made four “gravity assist” maneuvers. For these maneuvers, Rosetta passed close to Earth three times and Mars once, using the planets’ gravitation to increase its speed. Rosetta made observations of Mars and two asteroids as the craft passed by these objects. In June 2011, Rosetta was put into a state of “hibernation” until early 2014, keeping only the most essential parts running. During this part of the voyage, the solar-powered probe was too far from the sun to remain active.

Rosetta carried instruments to study the comet body, called the nucleus, as well as the gas and particles given off by the nucleus. Its instruments also studied the interaction of the comet with the solar wind, the constant flow of particles and radiation given off by the sun.

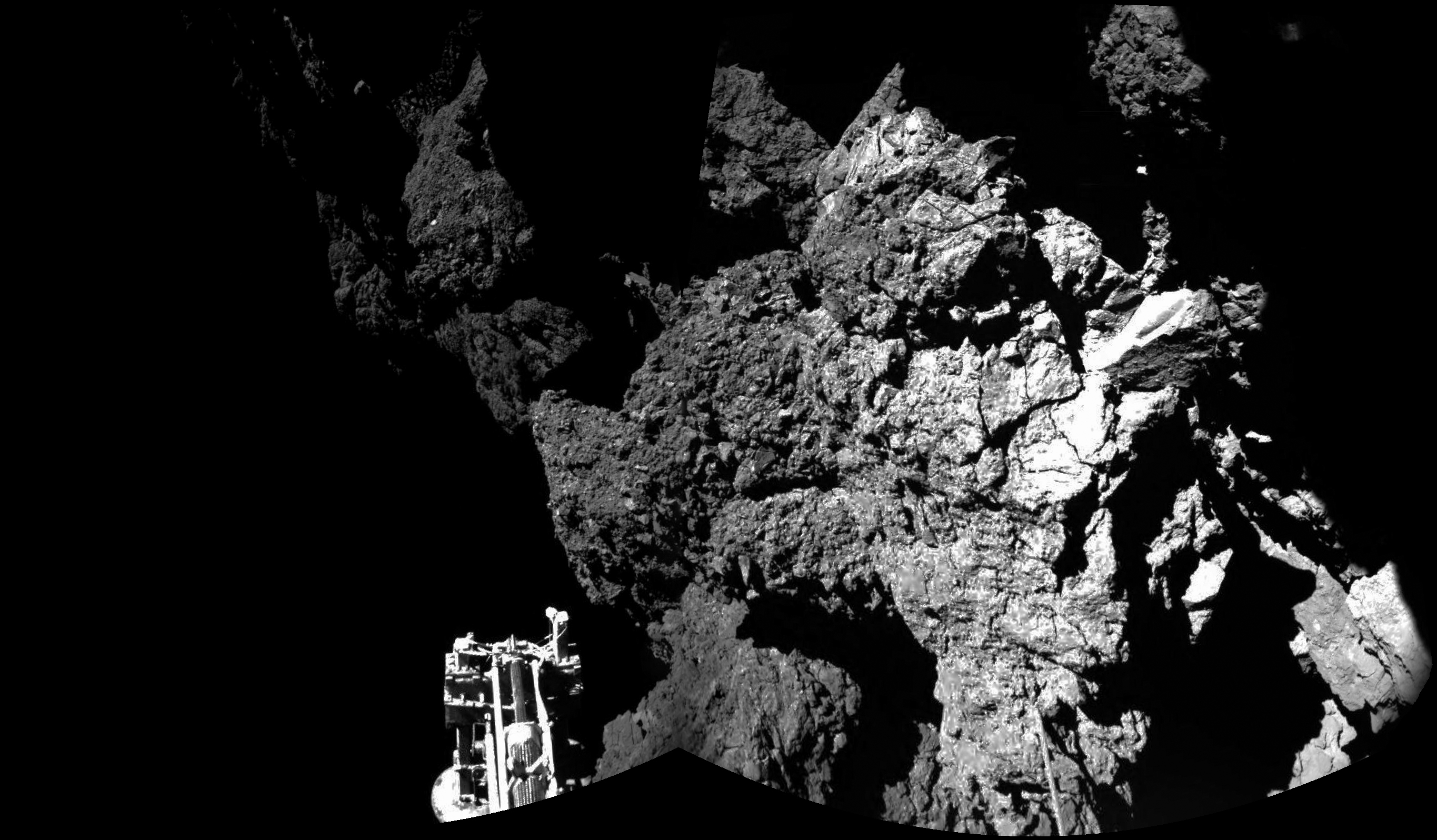

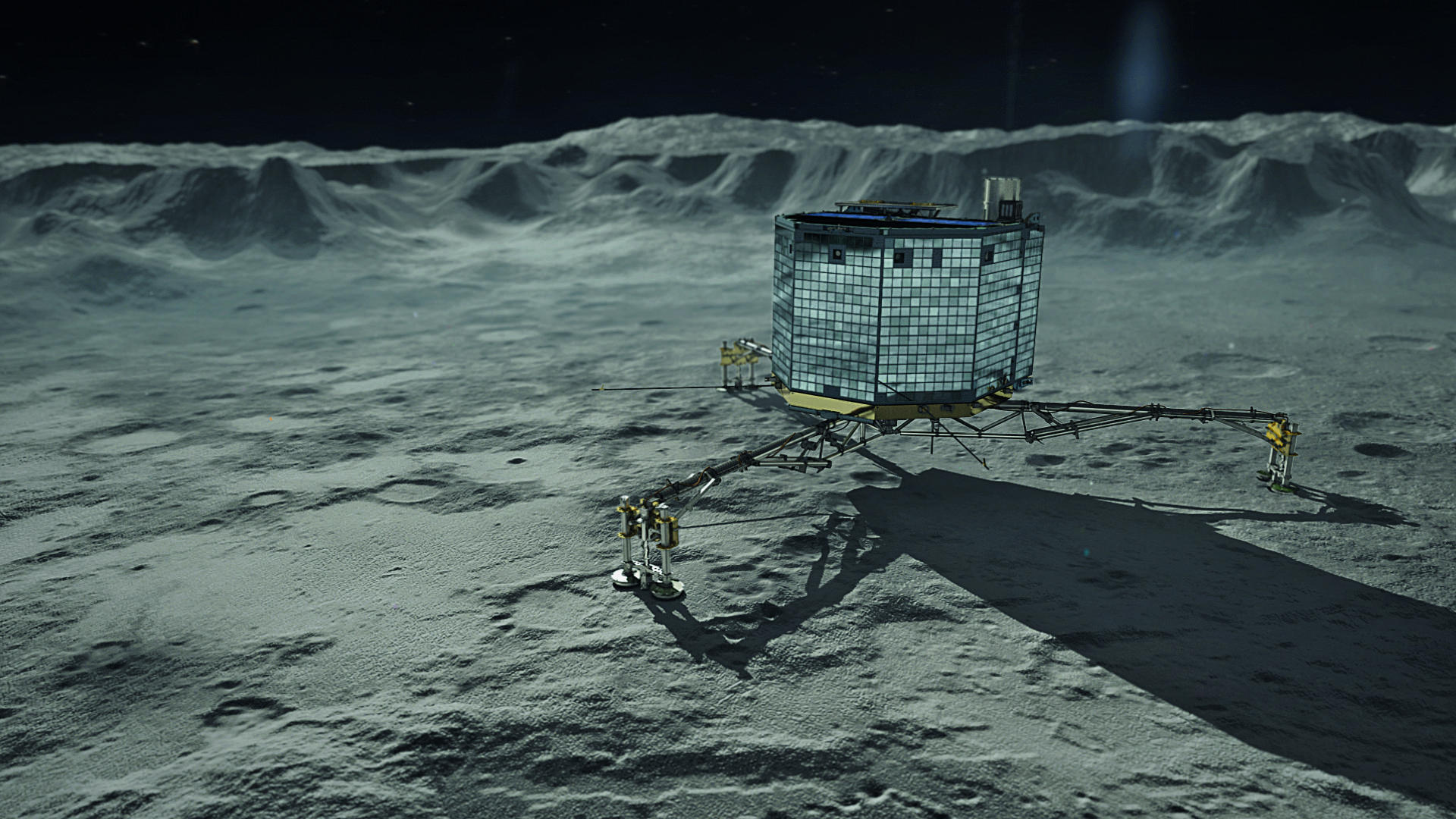

Rosetta also carried a small landing craft called Philae. The lander touched down on the nucleus on Nov. 12, 2014. Philae was equipped with harpoons that should have anchored it to the comet’s surface. However, the landing failed to trigger their deployment, and the lander rebounded an estimated 0.6 mile (1 kilometer) above the comet’s surface. The lander returned to the comet and bounced one more time before settling in a heavily shaded area of the nucleus. Without sunlight on its solar panels, Philae could not recharge its batteries. Thus, it could only make observations and take readings for about 2 1/2 days before the batteries were depleted. The ESA briefly reestablished contact with Philae in the summer of 2015, but the connection was not steady enough to conduct additional experiments. After months without further contact, ESA officials declared an end to Philae’s mission in 2016.

Rosetta detected organic molecules, such as amino acids, on 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko. This finding lent support to the hypothesis that shortly after Earth’s formation, bombardment by comets seeded the planet with materials necessary for the development of life. However, Rosetta found the ratio of water to heavy water on the comet was different than that found on Earth. Heavy water is water that includes a heavier isotope (form) of hydrogen called deuterium. This finding suggests that Earth’s water did not come from comets similar to 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko.

In September 2016, as the comet headed back toward the outer solar system, ESA scientists guided Rosetta to the nucleus, ending its mission. The probe continued to take photographs and gather data until just seconds before the collision.