Coral bleaching is a problem that affects living corals. It can cause stressed corals to lose their often vibrant colors and eventually die. Climate change due to global warming is a major cause of coral bleaching. Global warming is an observed increase in Earth’s average surface temperature driven by human activity. The warming of water temperatures by as little as 2 Fahrenheit degrees (1 Celsius degree) can trigger coral bleaching. Bleaching can also be triggered by extremely low tides, water pollution, or excessive sunlight.

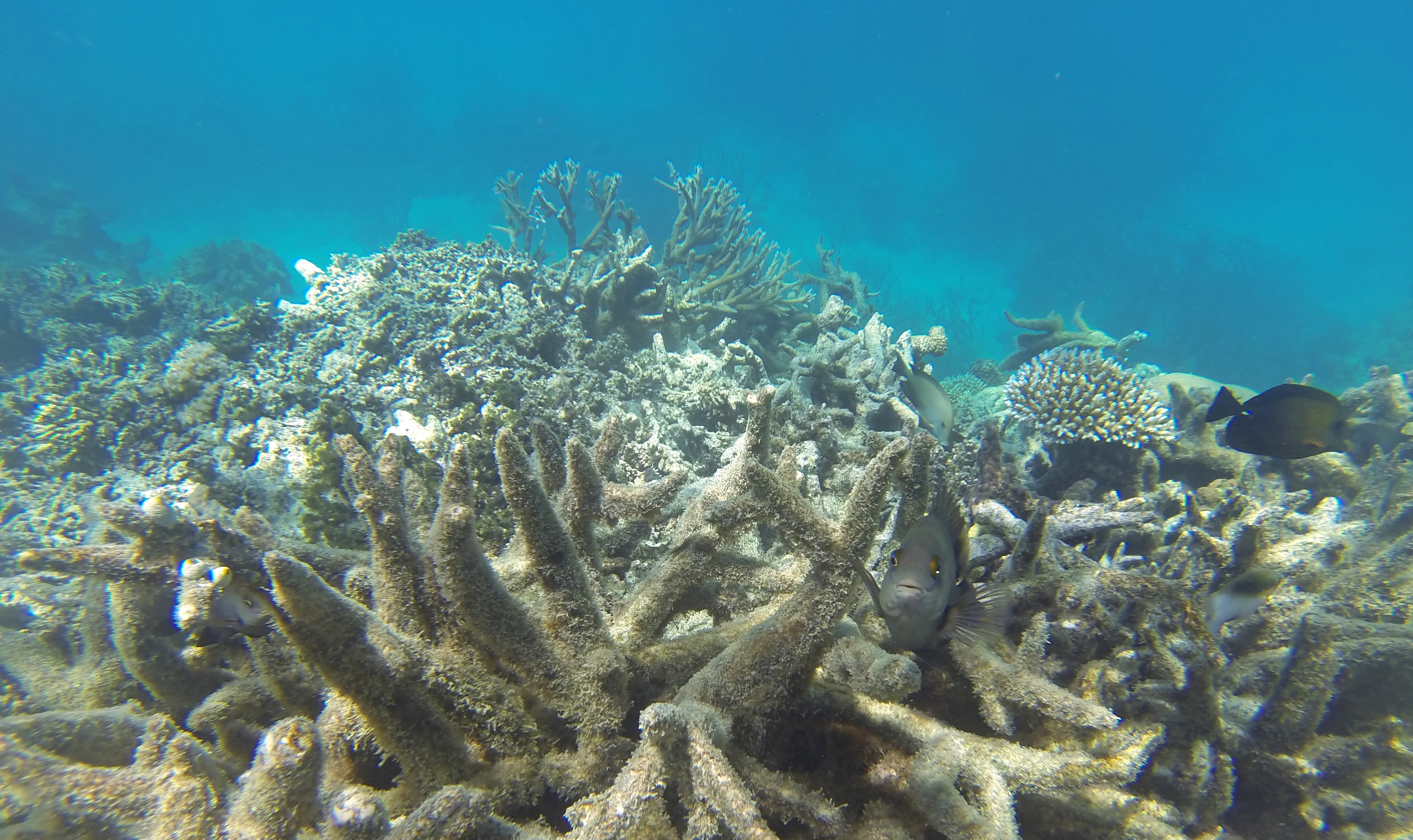

Living corals are made up of colonies of tiny creatures called polyps. The polyps are often attached to elaborate and beautiful limestone structures. These structures are made up of the skeletons of previous generations of polyps. Over many generations, the skeletons can accumulate to form enormous reefs. Coral reefs can provide homes for a huge variety of fish and other marine wildlife, forming the basis of some of the world’s richest ecosystems. An ecosystem is a community of living things and the nonliving things on which they depend.

Most reef-building corals cannot survive without single-celled algae called zooxanthellae, which live inside the polyps’ tissues. The tiny algae provide up to 90 percent of the coral’s food and help the corals to secrete their limestone skeletons. In addition, zooxanthellae provide much of living coral’s color. For reasons not entirely understood, stressed corals—such as those exposed to unusually warm seawater—will often eject zooxanthellae from their bodies. The loss of the colorful algae leaves the coral with a ghostly white appearance, giving coral bleaching its name.

If water temperatures recover quickly, the coral may take up the algae again, helping to limit long-term damage. If abnormally warm conditions continue, however, the coral can die. The decaying polyps serve as fertilizer for seaweed, which can overrun the remaining reef structure, contributing to the collapse of the entire ecosystem.

Reports of widespread bleaching were once relatively rare, leaving reefs time to recover between bleaching events. Since the early 1980’s, however, rising ocean temperatures have led to more frequent bleaching.

The first widespread reports of bleaching at Australia’s Great Barrier Reef, by far the world’s largest reef system, occurred in conjunction with the El Niño of 1982-1983. El Niño is a periodic weather pattern that can spread warm surface waters throughout much of the Pacific Ocean. Particularly strong El Niños occur about every two to seven years. Because they bring such great warmth, extreme El Niño years have been linked to widespread bleaching.

Bleaching in the El Niño year of 1997-1998 led the United States National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to declare its first-ever global bleaching event. Bleaching was reported at half the individual reefs that make up the Great Barrier Reef. Unusually warm temperatures produced another mass bleaching in the region in 2002, affecting 60 percent of the reefs. The El Niño of 2015-2016 triggered the worst bleaching yet observed at the Great Barrier Reef. The Australian Research Council (ARC) Center of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies announced that at least some bleaching had occurred in over 93 percent of the reef.

By 2020, non-El Niño ocean temperatures had become warmer than El Niño temperatures of the 1980’s, greatly increasing the risk of bleaching. Widespread bleaching occurred at the Great Barrier Reef again in 2017, 2020, and 2022.