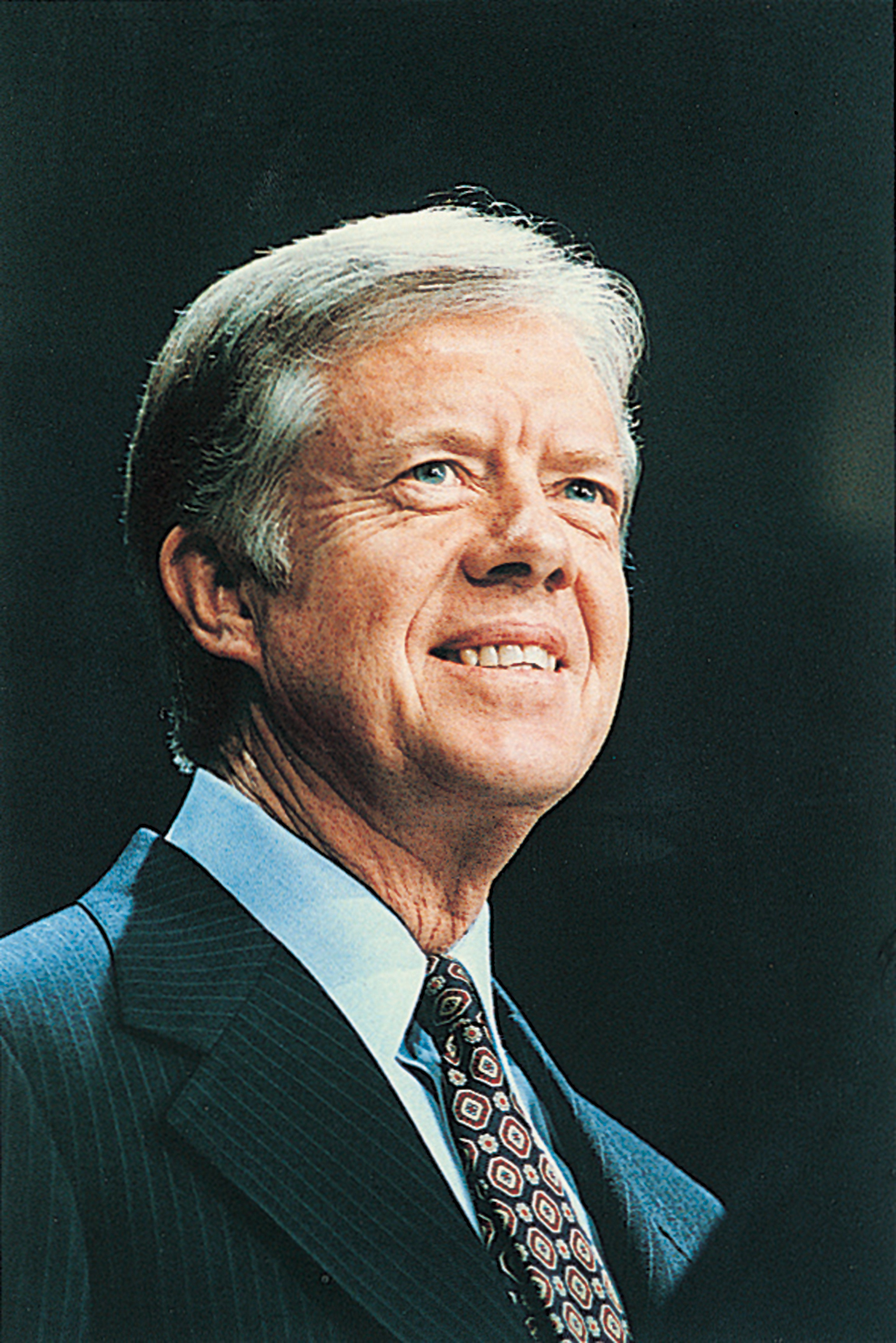

Carter, Jimmy (1924-…), was elected president of the United States in 1976, climaxing a remarkable rise to national fame. Carter had been governor of Georgia from 1971 to 1975 and was little known elsewhere at the beginning of 1976. But then he won 18 primary elections and became the Democratic candidate for president. Carter defeated President Gerald R. Ford in the 1976 election. In 1980, Carter was defeated in his bid for a second term by former Governor Ronald Reagan of California, his Republican opponent.

Before Carter won election as governor, he served in the Georgia Senate. He had managed his family peanut warehouse business and farm before entering politics. Carter also had been an officer in the United States Navy. He was the first graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy to become chief executive.

During Carter’s presidency, the United States faced problems both at home and abroad. At home, the economy suffered from unemployment and severe inflation. Abroad, relations between the United States and the Soviet Union plunged to their lowest point in several years following a Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. In Iran, a group of Americans were held hostage by revolutionaries who had taken over the U.S. Embassy in Tehran. The revolutionaries had seized the hostages to protest U.S. support for the deposed shah of Iran. Despite these problems, Carter won praise for some achievements in foreign affairs. He helped establish diplomatic relations between the United States and China. He also helped bring about a peace treaty between Egypt and Israel.

After leaving the presidency, Carter continued working to find peaceful solutions to international conflicts. He received the Nobel Peace Prize in 2002.

In appearance and manner, Carter was calm, reserved, and soft-spoken. His friends knew him as a man of great personal warmth and charm. In politics, Carter was an able, energetic campaigner with an iron will and a determination to win every fight. According to his political aides, he demanded hard work and set high standards but pushed himself the hardest.

Early life

Boyhood.

James Earl Carter, Jr., was born on Oct. 1, 1924, in Plains, Georgia. Throughout his life, he has been known by the nickname Jimmy. He had two sisters, Gloria (1926-1990) and Ruth (1929-1983), and a brother, William Alton III (1937-1988), usually called Billy.

Carter’s father, a farmer and businessman, ran a farm products store on the family farm in the rural community of Archery, a few miles west of Plains. Carter’s mother, Lillian Gordy Carter, was a registered nurse.

The Carters lived in Plains when Jimmy was born. Four years later, they moved to the farm in Archery. Jimmy grew up there and helped with the farm chores during his boyhood. He also developed an early interest in business. When the sandy-haired boy was about 5 years old, he began to sell boiled peanuts on the streets of Plains. He earned about $1 a day on weekdays and about $5 on Saturdays. At the age of 9, Jimmy bought five huge bales of cotton for 5 cents a pound. He stored the cotton and sold it a few years later, when the price had more than tripled.

Education.

Jimmy went to public school in Plains. He shared his mother’s love of reading and received good grades. A schoolmate later remembered that Jimmy “was always the smartest in the class.” The boy’s favorite subjects included history, literature, and music. As a teen-ager, he played on the high school basketball team.

In 1941, following graduation from high school, Carter entered Georgia Southwestern College in nearby Americus. In 1942, a boyhood dream came true when he received an appointment to the United States Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland. “Even as a grammar school child, I read books about the Navy and Annapolis,” Carter recalled. However, he lacked the mathematics courses required for admission to the academy and enrolled at Georgia Institute of Technology to fulfill this requirement. Carter entered the academy in 1943. He did especially well in electronics, gunnery, and naval tactics and graduated in 1946, ranking 59th in a class of 820.

Carter’s family.

In 1945, Carter had started to date Rosalynn Smith (Aug. 18, 1927-Nov. 19, 2023) of Plains. She was the best friend of his sister Ruth. Rosalynn’s father, a garage mechanic, died when she was 13 years old. She took a part-time job as cleaning girl in a beauty shop to help pay the family’s expenses.

Jimmy and Rosalynn were married on July 7, 1946, about a month after he graduated from Annapolis. They had four children: John William (1947-…), usually called Jack; James Earl III (1950-…), usually called Chip; Donnel Jeffrey (1952-…); and Amy Lynn (1967-…).

Naval career.

Carter spent his first two years in the Navy chiefly as an electronics instructor. He served first on the USS Wyoming and later on the USS Mississippi. These battleships were being used to test new equipment. Near the end of his period on the Mississippi, Carter volunteered for submarine duty. He graduated from submarine-training school in 1948, ranking third in a class of 52. Carter was then assigned to the submarine USS Pomfret and, in 1950, to the USS K-1, a submarine designed for antisubmarine warfare.

In 1952, Carter joined a select group of officers who were developing the world’s first nuclear-powered submarines. He became engineering officer of the nuclear submarine Sea Wolf. Carter served under Captain Hyman G. Rickover, who pioneered the nuclear project. Carter later wrote that Rickover “had a profound effect on my life—perhaps more than anyone except my own parents. … He expected the maximum from us, but he always contributed more.”

A turning point in Carter’s life occurred in 1953, when his father died of cancer. Carter felt he was needed in Plains to manage the family business. But Rosalynn had no desire to return to Plains, and she argued against his leaving the Navy. Carter later called their disagreement “the first really serious argument in our marriage.” He resigned from the Navy that year with the rank of lieutenant senior grade.

Return to Plains

Businessman and civic leader.

Soon after Carter returned to Plains, he took over the family farm and a peanut warehouse that his father had established in the town. He studied modern farming techniques at the Agricultural Experiment Station in Tifton, Georgia. During the late 1950’s and the 1960’s, Carter expanded the warehouse and bought new machinery for the farm. The family businesses thrived under his management.

Carter devoted much time to civic affairs. He served on the Sumter County Board of Education from 1955 to 1962, the last two years as chairman. Carter also became a deacon and Sunday-school teacher of the Plains Baptist Church and a member of the local hospital and library boards.

Carter was widely respected in Plains. But his views on racial issues often differed from those of most of his neighbors. He disapproved of the segregation laws that separated Black and white people in schools and other public facilities throughout the South. During the 1950’s, these laws came under increasing attack by federal courts and civil rights workers. Many Southerners formed local chapters of the White Citizens’ Council, an organization designed to help preserve segregation. A chapter was established in Plains in 1955, and Carter was asked to join. He refused to do so and declared that he would rather move from Plains.

In 1965, Carter’s church considered a proposal to ban Black worshipers from Sunday services. At that time, Black civil rights workers were trying to integrate various Southern churches. Carter urged his congregation to defeat the measure, but only his family and one other church member voted against it.

State senator.

In 1962, Carter ran for the Georgia Senate. He received a stormy introduction to state politics. On the day of the Georgia primary election, Carter saw voters marking their ballots openly in front of the election supervisor in the town of Georgetown. He charged that this action violated voting laws. But the election supervisor, who was the political boss of the area and a supporter of Carter’s opponent, ignored the protest.

The results of the primary election showed that Carter had lost by only a few votes. He angrily challenged the results in court. Just three days before the general election, he was declared to be the Democratic nominee. Carter beat his Republican opponent by about 1,000 votes. He was reelected to the Senate in 1964. As a state senator, Carter worked hard for reforms in education.

Steps to the governorship.

In 1966, Carter became a candidate for the Democratic nomination for governor of Georgia. He was defeated in the primary election. But Carter, determined to win the governorship, decided later that year to run for the office again in 1970. From 1966 to 1970, he worked to increase his understanding of Georgia’s problems and made about 1,800 speeches throughout the state.

In 1970, political experts gave Carter little chance of winning the Democratic nomination for governor. The heavily favored candidate was Carl E. Sanders, a liberal who had served as governor from 1963 to 1967. During the campaign, Carter opposed the busing of students to achieve racial balance in schools. He also took other stands that were important to Georgia’s rural, conservative voters. Carter’s critics charged he was appealing for the support of segregationists. Carter won the nomination. In the general election, he defeated his Republican opponent, Hal Suit, an Atlanta television newscaster, by about 200,000 votes.

Governor of Georgia

Carter began his term as governor in January 1971 and quickly made clear that he would work to aid all needy Georgians. In his inaugural address, he declared: “I say to you quite frankly that the time for racial discrimination is over. No poor, rural, weak, or Black person should ever have to bear the additional burden of being deprived of the opportunity of an education, a job, or simple justice.” This speech brought Carter his first nationwide attention.

Political reformer.

During Carter’s campaign for the governorship, he had promised to make the state government more efficient. Soon after he took office, he set up task forces of leaders from education, industry, and state government to study every state agency. One task force member later recalled that the new governor “was right there with us, working just as hard, digging just as deep into every little problem. It was his program and he worked on it as hard as anybody, and the final product was distinctly his.” As a result of this detailed study, Carter merged about 300 state agencies and boards into about 30 agencies.

Carter also pushed a series of reforms through the legislature. One of the most important ones was a law to provide equal state aid to schools in the wealthy and poor areas of Georgia. Other reforms set up community centers for children with intellectual disabilities and increased educational programs for convicts. At Carter’s urging, the legislature passed laws to protect the environment, preserve historic sites, and decrease secrecy in government. Carter took pride in a program he introduced for the appointment of judges and state government officials. Under this program, all such appointments were based on merit, rather than political influence.

Concern for Black citizens.

Carter opened many job opportunities for Black workers in the Georgia state government. During his administration, the number of Black appointees on major state boards and agencies increased from 3 to 53. The number of Black state employees rose by about 40 percent.

Carter also established a project to honor notable Black Georgians. In 1973, he appointed a committee to nominate Black people for the portrait galleries in the State Capitol. Pictures of many prominent Georgia men and women hung there, but none were of Black Americans. The committee’s first choice was Martin Luther King, Jr. A portrait of the famous civil rights leader was hung in the Capitol in 1974.

Plans for the presidency.

While serving as governor, Carter became increasingly active in national activities of the Democratic Party. He headed the 1972 Democratic Governors’ Campaign Committee, which worked to help elect the party’s candidates for governor. He also served as chairman of the Democratic National Campaign Committee in 1974.

At about the middle of his term as governor, Carter began to consider running for president in 1976. Georgia law prohibited a governor from serving two consecutive terms. But Carter also saw no heavy favorite for the Democratic presidential nomination. In addition, he believed that voters would support a leader from outside Washington, D.C., who offered bold, new solutions to the nation’s problems.

Carter’s mother later recalled that she learned in September 1973 of his plan to seek the presidency. She asked him what he intended to do after leaving the governorship, and Carter replied, “I’m going to run for president.” She asked, “President of what?” , and he answered: “Momma, I’m going to run for president of the United States, and I’m going to win.”

In December 1974, a month before his term as governor expired, Carter announced his candidacy for the 1976 Democratic presidential nomination. He was still little known outside Georgia.

Presidential candidate

Rise to prominence.

Carter began to work full time for the presidential nomination soon after leaving office as governor in January 1975. He campaigned outside Georgia for about 250 days that year, but his campaign attracted little public attention. In October 1975, a public opinion poll that ranked possible contenders for the Democratic presidential nomination did not even mention Carter.

In January 1976, Carter began a whirlwind rise to national prominence. That month, he received the most votes in an Iowa caucus, the first contest to elect delegates to the 1976 Democratic National Convention. In February, Carter won the year’s first presidential primary election, in New Hampshire. By then, 10 other Democrats were seeking the nomination. Carter’s chief opponents were Senator Henry M. Jackson of Washington, Representative Morris K. Udall of Arizona, and Governor George C. Wallace of Alabama. In March, Carter beat Wallace in the Florida primary election. Soon afterward, a public opinion poll showed that Carter was the top choice of Democrats for the presidential nomination.

Many voters liked Carter largely because he had not served in Washington, D.C. He became a symbol of their desire for a leader without ties to various interest groups in the nation’s capital. Carter also attracted much support with his vow to restore moral leadership to the presidency. Public confidence in government had been shaken by the Watergate scandal, which led to the resignation of President Richard M. Nixon (see Watergate ). Vice President Gerald R. Ford succeeded Nixon as president. But Ford’s popularity fell sharply after he pardoned Nixon for any federal crimes Nixon may have committed as president.

Carter easily won the nomination for president on the first ballot at the Democratic National Convention in New York City. At his request, Senator Walter F. Mondale of Minnesota was nominated for vice president. The Republicans nominated Ford and his vice presidential choice, Senator Robert J. Dole of Kansas.

The 1976 election.

Many political observers believed that Carter’s nomination would unite the Democratic Party. Since 1964, millions of conservative Democrats in the South had supported Republican presidential candidates. But in 1976, most of these men and women were expected to vote for Carter.

In the presidential campaign, Carter charged that Ford had failed to deal effectively with high unemployment. During the autumn of 1976, about 8 per cent of the nation’s workers had no jobs. Carter promised to help create more jobs by increasing federal spending and encouraging business expansion. Ford argued that Carter’s plans would lead to rapid inflation. Carter also pledged to consider pardons for Vietnam War draft evaders, to reorganize the federal government, and to develop a national energy policy.

In the 1976 presidential election, Carter defeated Ford by 1,682,970 popular votes, 40,830,763 to 39,147,793. Other candidates received about 1,580,000 votes. Carter won 297 electoral votes and Ford won 240 electoral votes. Former Governor Ronald Reagan of California received 1 electoral vote.

Carter’s administration (1977-1981)

Early programs.

Carter’s first major decision as president was to pardon draft evaders of the Vietnam War period. Later in 1977, he approved a plan to review and possibly upgrade the less-than-honorable discharges of deserters and other military law violators of the Vietnam era. These actions fulfilled one of Carter’s most controversial campaign pledges.

Loading the player...Jimmy Carter's inaugural address

The president succeeded in winning quick congressional passage of several major measures. In March 1977, Congress approved his request for the authority to eliminate or consolidate federal agencies that he felt duplicated services. Soon afterward, Carter won congressional passage of legislation to lower federal income taxes. In August 1977, Congress adopted the president’s proposal to establish a new executive department—the Department of Energy.

During the 1976 presidential campaign, Carter had often charged that the program to produce B-1 bombers was “wasteful.” The cost of the program was estimated at over $25 billion. Many military officials and members of Congress had argued that the U.S. Air Force needed about 245 of these bombers. But in June 1977, Carter halted manufacture of the B-1 and instead supported development of the cruise missile. Cruise missiles can be launched from airplanes or submarines and can be directed to avoid enemy defenses.

The national scene.

During Carter’s first year as president, the nation’s economy improved and unemployment fell. But in 1978, inflation became a major problem. In an attempt to fight inflation, Carter urged businesses to avoid big price increases and asked labor leaders to hold down wage demands. But these steps had little effect on inflation.

In 1978, Carter won congressional approval of a national energy program. The energy legislation was designed largely to reduce U.S. oil imports. The legislation included tax penalties for owners of automobiles that used excessive amounts of gasoline. But, despite this legislation, oil imports remained at a high level, and inflation grew steadily worse. In 1979, continuing high inflation and gasoline shortages contributed to a sharp drop in Carter’s performance rating in public opinion polls.

In July 1979, the president asked his entire Cabinet to submit their resignations for his consideration. Carter then made six Cabinet changes in hopes of strengthening his administration. Carter also named Hamilton Jordan, one of his presidential assistants, to the newly created position of White House chief of staff.

In September 1979, Congress adopted Carter’s proposal to establish a Cabinet-level Department of Education. The Department of Health, Education, and Welfare was renamed the Department of Health and Human Services.

In March 1980, Carter announced a new program to fight inflation. The program included cuts in federal spending, a tax on imported oil, and voluntary restraints on wages and prices. Carter also ordered restrictions on credit cards and certain other types of consumer credit. Despite these measures, prices continued to rise. The rate of inflation soared to about 15 per cent for the first half of 1980. In 1976, the year before Carter took office, the inflation rate had been less than 6 per cent. In July 1980, a public opinion poll showed that only 21 per cent of Americans approved of Carter’s performance, the lowest score on record for any president.

Foreign affairs.

Carter attracted worldwide attention in 1977 when he strongly supported the struggle for human rights in the Soviet Union and other nations. Carter limited or completely banned U.S. aid and exports to some nations whose governments he believed to be violating human rights. Most of these nations were in Africa, Asia, and Latin America.

The president achieved one of his major foreign policy goals in 1978. In that year, the U.S. Senate ratified two treaties concerning the Panama Canal, which the United States had controlled since its construction in the early 1900’s. One treaty specified that Panama would gain control of the canal on Dec. 31, 1999. The other treaty gave the United States the right to defend the canal’s neutrality.

Also in 1978, Carter strengthened official ties between the United States and the Communist government of China. The two nations established full diplomatic relations with one another in 1979.

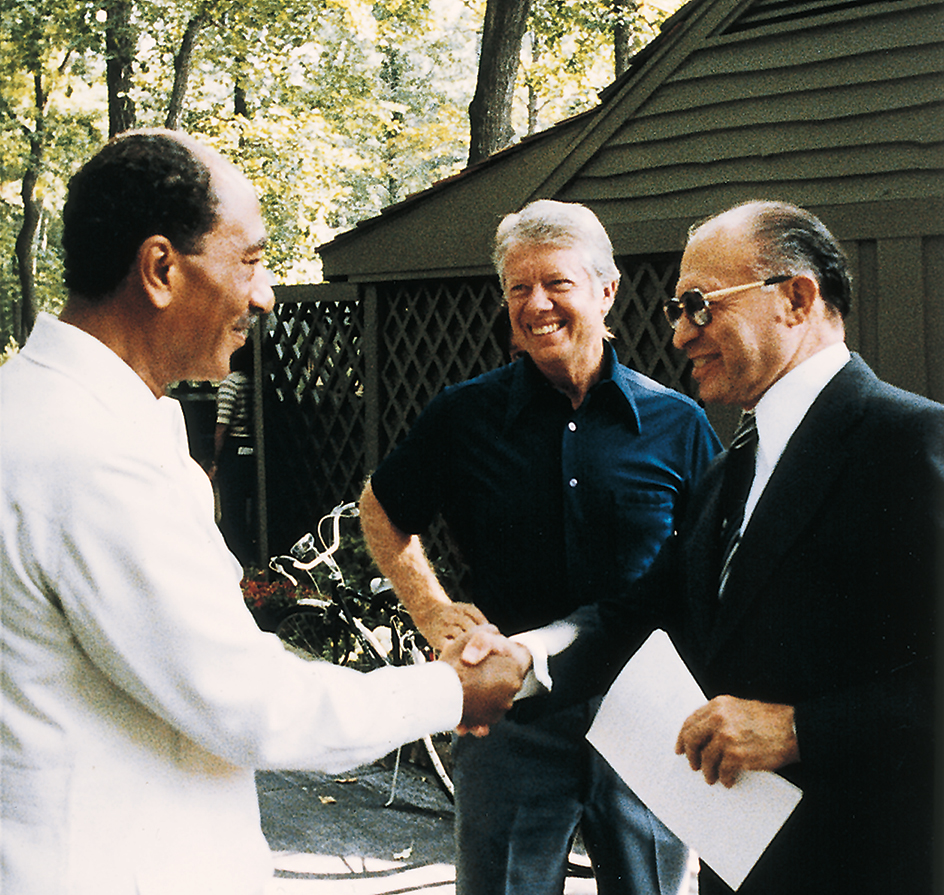

The president received much praise for his efforts in bringing about a peace treaty between Egypt and Israel. In 1978, he arranged meetings in the United States between himself and President Anwar el-Sadat of Egypt and Prime Minister Menachem Begin of Israel. Carter helped work out a major agreement that included a call for the creation of a peace treaty between Egypt and Israel. The two nations adopted the treaty in 1979. See Middle East (The 1970’s and 1980’s) .

Also in 1979, the Carter administration and Soviet officials negotiated a treaty to limit the use of nuclear weapons by the United States and the Soviet Union. The treaty, called SALT II, resulted from the second round of Strategic Arms Limitations Talks. It would not take effect unless it was approved by the U.S. Senate. Opponents of SALT II argued that it would weaken the U.S. defense system. Supporters believed the treaty was necessary to slow the arms race.

In late 1979 and early 1980, the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan, and Soviet-American relations plunged to their lowest point in several years. At Carter’s urging, the United States and many other nations refused to participate in the 1980 Summer Olympic Games in Moscow as a protest against the invasion. Carter also asked the U.S. Senate to postpone consideration of the SALT II treaty.

The Iranian crisis.

In February 1979, a movement led by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, a Muslim religious leader, overthrew the government of the shah of Iran. The shah, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, had left Iran in January. In October, Carter allowed the deposed shah to enter the United States for medical treatment. The next month, Iranian revolutionaries took over the United States Embassy in Tehran, the capital of Iran. They seized a group of U.S. citizens, most of whom were embassy employees, and held them as hostages. They demanded that the United States return the shah to Iran for trial in exchange for the prisoners.

Carter denounced the Iranians’ action as a violation of international law, and he refused to meet their demands. Trying to force the release of the hostages, he banned imports from Iran. He also cut diplomatic relations between the two countries.

In April 1980, Carter authorized an armed rescue mission to attempt to free the hostages. The mission ended in failure after three of its eight helicopters broke down while flying through a sandstorm. After the project had been canceled, a fourth helicopter crashed into a transport plane. Both aircraft exploded, killing eight men. Secretary of State Cyrus R. Vance, who had opposed the rescue attempt, resigned. Carter named Senator Edmund S. Muskie of Maine as Vance’s successor. In July, the former shah died in Egypt, but the Iranian revolutionaries continued to hold the hostages to protest American policies toward their country. They finally released the Americans on Jan. 20, 1981, the day Carter left office.

Life in the White House.

Carter ended much of the ceremony and pageantry that had marked official receptions in the White House. For example, he eliminated the practice of having trumpeters announce the presidential family and of having a color guard precede it. Most state dinners ended about 11 p.m., far earlier than those of most previous presidents. Carter conducted official business during some state functions in the White House and worked after others.

The Carters’ daughter, Amy, was 9 years old when her father became president. She attended public schools near the White House. Amy often enlivened the White House by bringing classmates there to play.

Rosalynn Carter became an active representative of Carter’s administration. In 1977, she led a U.S. delegation on a tour of Latin America. She also worked to help women gain equal rights and to improve care for the elderly and the mentally ill.

The 1980 election.

Senator Edward M. Kennedy of Massachusetts challenged Carter for the 1980 Democratic presidential nomination. In August 1979, polls showed that Democrats preferred Kennedy over Carter by a huge margin. But Carter regained popularity during late 1979 and early 1980, partly for his handling of the Iranian crisis. He won enough delegates in primary elections to gain renomination on the first ballot at the Democratic National Convention in New York City. Mondale again became his running mate. The Republicans chose former Governor Ronald Reagan of California for president and George H. W. Bush, former U.S. ambassador to the United Nations (UN), for vice president. Representative John B. Anderson of Illinois and his running mate, former Governor Patrick J. Lucey of Wisconsin, ran as independent candidates.

In the presidential campaign, Carter stressed such achievements as his energy program and the Egyptian-Israeli peace treaty. Reagan charged that Carter had failed to deal effectively with inflation and high unemployment. Carter lost the 1980 election by a wide margin. He received about 35 million popular votes to about 44 million for Reagan, but he got only 49 electoral votes to Reagan’s 489. Carter carried six states and the District of Columbia. Reagan carried 44 states.

Later years

Carter returned to Plains after leaving the White House. In 1982, he founded the Carter Center of Emory University as a forum for the discussion of national and international issues. Since the mid-1980’s, Carter has worked as a volunteer carpenter on projects for Habitat for Humanity, a nonprofit organization that builds houses for the poor. The Carter Presidential Center was completed in Atlanta in 1986. It includes the Carter Center of Emory University and the Jimmy Carter Library and Museum.

Since the late 1980’s, Carter has helped monitor elections in a number of developing countries. In 1991, he founded the International Negotiation Network Council. The council consists of former heads of state and other prominent people willing to conduct peace negotiations or monitor elections. Also in 1991, Carter launched the Atlanta Project to coordinate government and private efforts to solve social problems that affect poor families. In 1994, he traveled to North Korea to help reduce tensions between that country and the United States over North Korea’s suspected development of nuclear weapons. Carter helped bring about negotiations. In 1991, military leaders in Haiti seized control of the government from the president. In 1994, Carter went to Haiti and helped persuade the leaders to return the president to office.

In 1999, Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter each received the Presidential Medal of Freedom. In December 1999, Jimmy Carter represented the United States in a ceremony in Panama in which the United States turned over control of the Panama Canal to Panama. In 1977, Carter had signed the treaty that said Panama would gain control of the canal at the end of 1999.

In May 2002, Carter made a historic trip to Cuba at the invitation of President Fidel Castro in an attempt to improve relations between the United States and Cuba. He became the most prominent American political leader to visit Cuba since Castro took power in 1959. There, in a live television address, Carter urged the Cuban government to adopt democratic reforms and called on the United States to end its embargo on trade with Cuba.

In 2002, Carter was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. He received the prize for his efforts to find peaceful solutions to international conflicts and to advance democracy and human rights.

Carter wrote a number of books after leaving the presidency, including the memoirs Keeping Faith: Memoirs of a President (1982), An Hour Before Daylight: Memories of a Rural Boyhood (2001), and Sharing Good Times (2004). He wrote Everything to Gain: Making the Most of the Rest of Your Life (1987) with his wife, Rosalynn. He also wrote a novel, The Hornet’s Nest (2003). The story is set in the South during the American Revolution (1775-1783) and focuses on characters on both sides of the conflict. In Palestine: Peace Not Apartheid (2006), he offers his views on the conflict between the Israelis and the Palestinians. His book The Craftsmanship of Jimmy Carter (2017) details Carter’s lifelong love of woodworking. Carter won Grammy Awards for his recordings of his books Our Endangered Values: America’s Moral Crisis (2005), A Full Life: Reflections at Ninety (2015), and Faith: A Journey For All (2018).

In 2006, Carter’s oldest son, Jack Carter, won the Democratic nomination for U.S. senator representing Nevada. Former President Carter appeared with his son at several campaign fundraising events, but Jack Carter lost the race to incumbent Republican Senator John Ensign.

In August 2015, Jimmy Carter announced that doctors had removed a cancerous mass from his liver and had discovered cancer spots on his brain. Carter underwent months of radiation treatments to treat the condition. Rosalynn Carter died on Nov. 19, 2023, at the age of 96.