Cartoon is a drawing or series of drawings that tells a story or expresses a message. Cartoonists simplify pictures to increase their power of communication. Cartoonists use a visual language much like writers use words. A few lines in a cartoon may carry a wealth of information. By leaving out certain details, the cartoonist can focus attention on other, more important aspects of the people, places, and things that the pictures portray. This may also help readers or audiences project themselves into the cartoon and allow them to relate to the characters and situations portrayed.

People throughout the world enjoy cartoons. Cartoons appear as animated motion pictures in movie theaters and on television. They also appear in comic strips and comic books, advertisements, and a wide variety of merchandise. Cartoons are particularly popular in children’s entertainment. Many children respond to cartoons. Many are able to recognize them and produce their own simple cartoons at an early age. Although many cartoons are directed at young people, some cartoons are intended specifically for an adult audience.

The term cartoon originally described a simple preliminary drawing that an artist during the mid-1600’s prepared as a plan for a painting, tapestry, or other work of art. Centuries later, the word was used to describe the completed, though simple, illustrations in European and American humor magazines. The use of cartoon art in animated films is so common that such films are often called cartoons.

Kinds of cartoons

There are several kinds of cartoons, including (1) editorial, (2) single panel, (3) illustration, and (4) advertising. For information on motion-picture cartoons, see Animation. For information on cartoons in comic strips and comic books, see Comics.

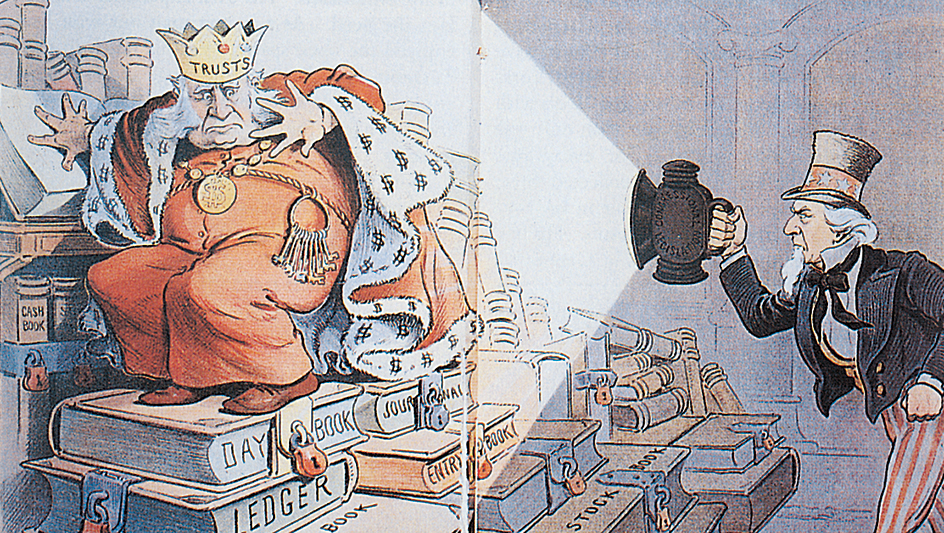

Editorial cartoons

accomplish in pictures what editorials do in words. An editorial cartoon encourages a reader to develop an opinion about someone or something prominent in the news. Most editorial cartoons appear as single panels on the editorial pages of newspapers. Some have captions or titles. Others consist only of a drawing. Editorial cartoons may support an editorial of the day, or they may deal with a news event or current social issue. Many editorial cartoonists use an exaggerated form of drawing called a caricature to poke fun at well-known people (see Caricature).

Editorial cartoons have been an important part of newspapers and magazines since the mid-1800’s. In 1841, editorial cartoons began appearing in the British comic magazine Punch. Weekly magazines in the United States started to feature them in the 1850’s. Influential cartoonists included Thomas Nast in Harper’s Weekly and Joseph Keppler in Puck. Nast introduced the elephant as the symbol of the Republican Party and the donkey as a symbol of the Democrats. Keppler popularized the concept of using historical or literary references to make a modern political point.

In the late 1800’s, editorial cartoons became regular features in daily newspapers. Newspaper cartoonists used less detail and a looser style than magazine cartoonists. The use of editorial cartoons in magazines declined because cartoons in daily newspapers were able to comment on news more quickly. More recently, the use of editorial cartoons in newspapers has begun to decline with the rise of cartoons in digital media.

The Pulitzer Prizes in journalism have included a cartoon category since 1922. For a list of winners, see Pulitzer Prizes.

Single-panel cartoons,

like editorial cartoons, have been popular since the mid-1800’s. This type of cartoon remained popular in magazines after most editorial cartoons had migrated to newspapers.

The humorous gag cartoon is the most common single-panel cartoon. It is often accompanied by a caption consisting of words spoken by a character in the panel.

In The New Yorker magazine, such cartoonists as James Thurber, Charles Addams, and Peter Arno turned the gag cartoon into a powerful tool for sophisticated social commentary. Others, such as Saul Steinberg and William Steig, explored cartooning as an art form in The New Yorker. Such cartoonists explored the idea that a picture and a caption could have a meaning together that neither had separately. In newspapers, single-panel cartoons usually appear next to the daily comic strips.

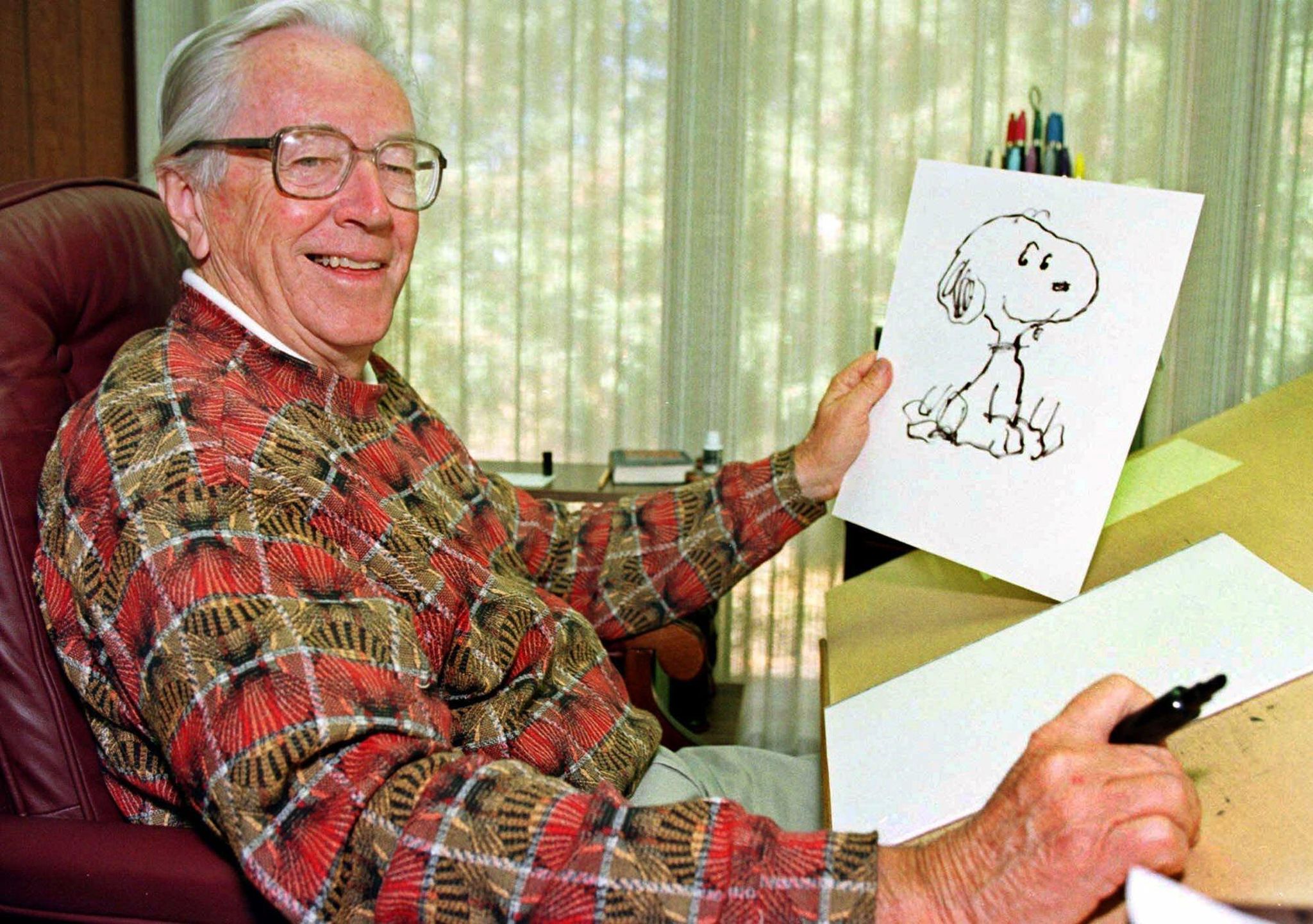

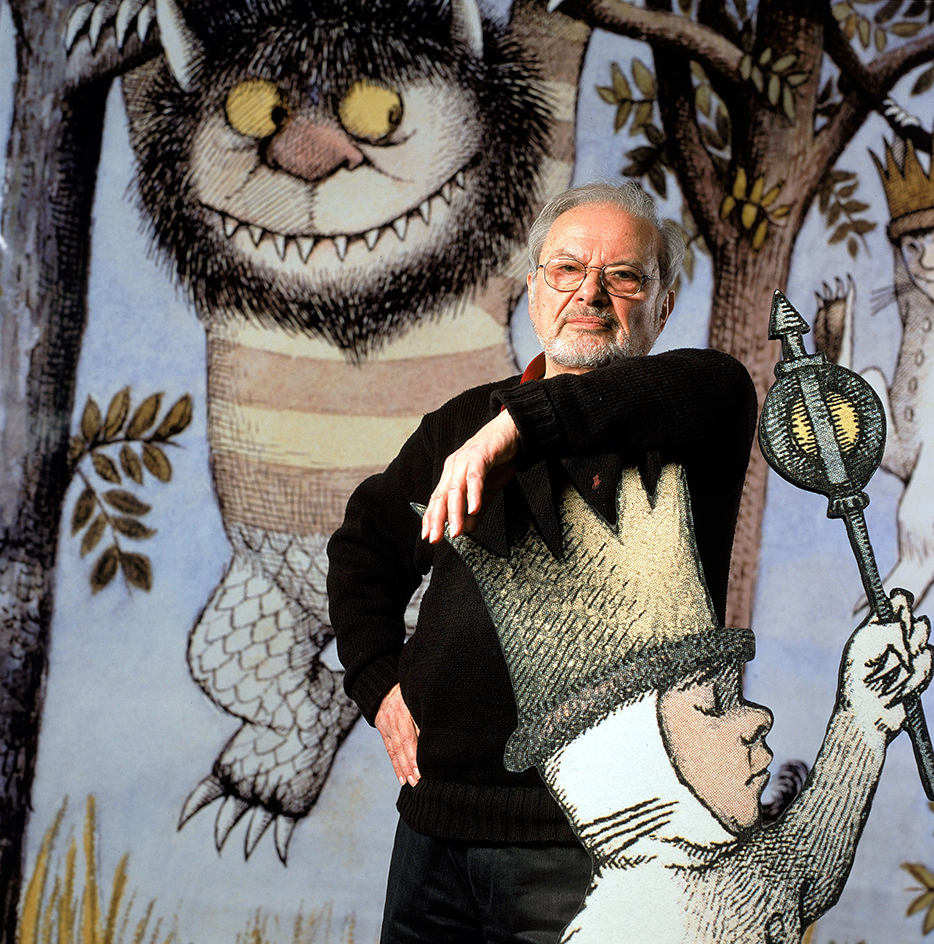

Illustration.

Cartoons are an important part of children’s book illustration. Many children’s authors, including Dr. Seuss and Maurice Sendak, have successfully combined cartooning with book illustration. See Literature for children.

Cartoons are occasionally used as book illustration for adult audiences, generally for such lighter works as collections of jokes or humorous stories. Instructional manuals and some nonfiction books may use diagrams containing cartoons. Cartoons are often used in diagrams because they eliminate much of the distracting detail that would be included in photographs.

Advertising

makes frequent use of the cartoon’s ability to clarify the messages of the service or product being sold. Many companies use popular cartoon characters to endorse their products.

Creating a cartoon

Developing the idea.

Cartoonists develop ideas for their drawings in several ways. Many editorial cartoonists work on a newspaper staff. These cartoonists meet with their editors to discuss the day’s news and decide which events deserve editorial comment. Then the cartoonist sketches several ideas, and the editor of the editorial page selects one to be completed. Some top editorial cartoonists on newspaper staffs have considerable control in the selection of material to be used. Other editorial cartoonists sell their work directly to clients or through a company called a syndicate that distributes their material to multiple clients.

Gag cartoonists may develop their own ideas or work with the ideas of writers. Comic-strip and comic-book artists may also team with a writer.

Cartoonists who draw illustrative and advertising cartoons tend to work from manuscripts supplied by writers or editors. These cartoonists must create cartoons that emphasize or clarify key points of the text.

Producing the finished cartoon.

Depending on his or her own style—and the editor’s requirements—a cartoonist may take from 30 minutes to a day to create a gag cartoon or comic strip. A comic-book page may require one-half to three days of work to fully write and draw.

Most cartoonists begin with a penciled outline. They go over the outline with a pen or brush dipped in India ink or with a felt- or nylon-tip marker. A few cartoonists work directly in ink. Others may work with a digital process that looks like ink but allows erasure.

The cartoonist may draw parts of the cartoon over and over again and then piece the parts together. This piecing does not show in the printed version, nor do any guideline elements used to create each drawing.

Shaded areas and areas of solid black help to create contrast in a cartoon. Traditional methods of shading include drawing a series of thin lines close together or pasting down pieces of thin plastic on which a pattern of dots or lines has been printed. In another traditional method, editorial cartoonists draw with a brush on rough-textured paper or on chemically treated paper with preprinted patterns. They then shade with a grease crayon. For information on how cartoons are reproduced for publication, see Printing.

Increasingly, cartoonists in all fields are turning to computer graphics programs to handle elements of lettering, coloring, and rendering. Some cartoonists have begun to use computers for all aspects of cartoon art.