Atrial fibrillation is the most common type of arrhythmia (abnormal heart rhythm). An arrhythmia occurs when the heart beats too fast or slow or in an irregular way. Atrial fibrillation is often abbreviated as afib. Untreated, afib greatly increases a person’s risk for stroke or heart failure, a condition that occurs when the heart is unable to pump blood efficiently.

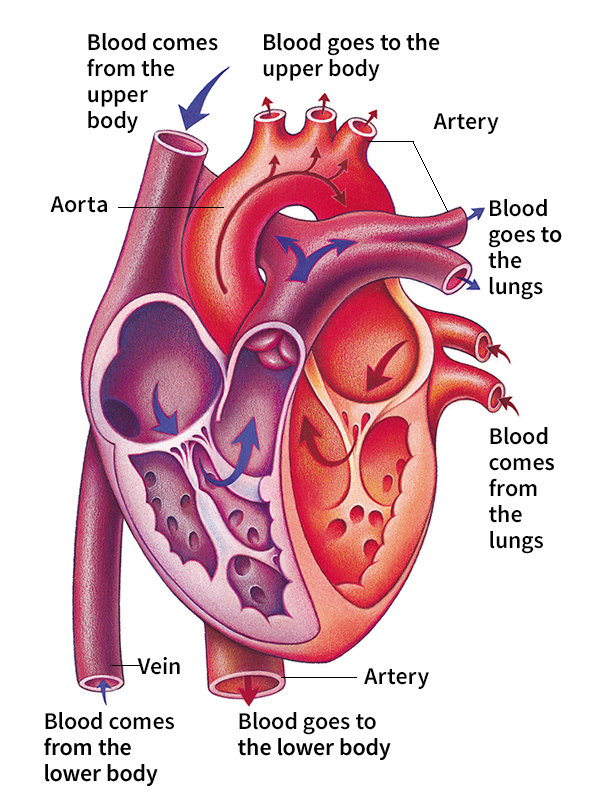

Normally, the heart’s upper chambers, called atria, beat in a steady rhythm. This beating efficiently moves blood into the heart’s lower chambers, called the ventricles, which pump it out to the rest of the body.

In atrial fibrillation, the atria fibrillate (quiver) rapidly instead of beating in a steady rhythm. The atria quiver so fast that they cannot fill the ventricles with blood. Blood pools in the atria, which may lead to the formation of blood clots. Blood clots may break away and move from the heart to other parts of the body, where they may cause a stroke.

Symptoms of afib may be mild or even unnoticed by people with the condition. Common symptoms include palpitations (sensations of a fast or pounding heartbeat), dizziness, fatigue, shortness of breath, and chest pain. Episodes of afib may come and go, or they may be persistent (lasting). The most common cause of atrial fibrillation is problems with the heart’s structure that generates electrical impulses to initiate a heartbeat. The risk of developing afib increases with age and with such conditions as diabetes, high blood pressure, and other forms of heart disease. However, some people who experience atrial fibrillation have no known heart problems.

Physicians diagnose afib using an electrocardiograph(ECG), an instrument that detects the electrical impulses produced by the heart. Treatment may include medications to prevent blood clots or to slow and reset the heart rhythm. Surgical procedures may also block the faulty electrical impulses that cause the arrhythmia, restoring a normal heartbeat.

See also Heart (Abnormal heart rhythms).