Cattle are among the most important farm animals. People eat the meat of cattle as roast beef, veal, hamburger, and hot dogs. People drink the milk of cattle and use it to make butter, cheese, and ice cream. The hides of cattle provide leather for shoes. Cattle also furnish materials for such useful items as medicines, soap, and glue. In some countries, cattle supply power by pulling plows, carts, and wagons. In some parts of the world, a family’s wealth is judged by the number of cattle it owns.

All kinds of cattle have large bodies, long tails, and cloven (divided) hoofs. Some cattle have horns. Cattle chew their food two separate times to digest it. After they chew and swallow the food, they bring it up from the stomach and chew it again. This once-swallowed food is called a cud.

Cattle are less intelligent than many other domestic animals. People sometimes name them. But cattle rarely learn to respond to their names as horses and dogs do.

Cattle roam and graze in green pastures and on the plains. Their mooing, or lowing, often breaks the silence of the countryside. Beef cattle are raised for their meat. Dairy cattle are raised for their milk. Dual-purpose cattle provide both meat and milk.

Loading the player...Cow moo

People around the world raise cattle. Cattle live in cold lands, such as Canada and Iceland, and in hot countries, such as Brazil and India. Hindus in India believe cattle are holy animals. They do not kill cattle or eat beef.

The word cattle usually means cows, bulls, steers, heifers, and calves. A cow is a female, and a bull is a male. Steers are males that have had some of their reproductive organs removed. A young cow is called a heifer until she gives birth to a calf. A calf is a young heifer or bull. The mother of a calf is called a dam, and the father is a sire. A group of cattle is known as a herd.

Beef cattle and dairy cattle that can be traced through all their ancestors to the original animals of a breed are called purebred. A registered animal is one whose family history has been recorded with the appropriate breed association in its register, called a herdbook.

Not all purebred cattle are registered. Some farmers and ranchers have no interest in registering their cattle.

The bodies of cattle

Cattle have muscular bodies, especially at maturity (full growth). Most cattle reach a height of about 4 to 6 1/2 feet (1.2 to 2 meters). Cows weigh from about 900 to 2,000 pounds (410 to 910 kilograms). Bulls may weigh 2,000 pounds or more.

Many cattle have black, white, or red coats of hair. Others have coats that are various shades or combinations of shades of these colors. Most cattle have a coat of short hair that grows thicker and somewhat longer during the winter. A few breeds have long hair. The long, shaggy hair of Galloway cattle enables them to survive the extremely cold weather in Scotland, where the breed developed and where most of them are raised. Cattle also have a long tail, which they use to shoo away insects.

Teeth.

Adult cattle have 32 teeth—8 in the front of the lower jaw and 12 each in the back of the upper and lower jaws. A cow cannot bite off grass because it does not have cutting teeth in the front of its upper jaw. It must tear the grass by moving its head. Cattle chew their cud with their molars (back teeth).

Horns.

The horns of cattle are hollow and have no branches, as do those of some other horned animals such as deer. Cattle born without horns are called polled cattle. Cattle owners have increased the number of polled animals through selective breeding. They dehorn (remove the horns of) most horned cattle to keep them from injuring other cattle or people. The horns are removed with chemicals, a hot iron, or a cutting tool. In most cases, dehorning occurs when a calf is less than 3 weeks old.

Stomach.

Cattle have a stomach with four compartments. This kind of stomach enables them to bring swallowed food back into their mouth to be chewed and swallowed again. Animals with such stomachs are called ruminants (see Ruminant). The compartments are the rumen, the reticulum, the omasum, and the abomasum.

When cattle eat, they first chew their food only enough to swallow it. The food goes down the esophagus (food pipe) into the rumen. The rumen and the reticulum form a large storage area. In that area, the food is mixed and softened. At the same time, microorganisms that grow in the rumen break down complex carbohydrates into simple carbohydrates. Such simple carbohydrates as sugars and starches provide the major source of energy for the animal. The microorganisms also build protein and many B-complex vitamins.

After the solid food has been mixed and softened, stomach muscles send it back up into the animal’s mouth. The animal rechews this cud and swallows it. The swallowed cud goes back to the rumen and reticulum, where it undergoes further chemical breakdown. The food and fluids then move down into the omasum, where much of the water is absorbed. The food then enters the abomasum. The walls of the abomasum produce digestive juices. These juices further digest the food. The abomasum is called the true stomach, because it functions in much the same way as the stomach of creatures that are not ruminants. From the stomach, the food goes to the intestine, where digestion and absorption are completed.

Udder.

Cows have a suspended organ called an udder, which holds their milk. The udder hangs from the cow’s body between and in front of the hind legs. The udder has four sections that hold milk. When a farmer milks a cow by hand, pressure causes the cow’s milk to squirt out of the udder through large nipples called teats.

Today, farmers rarely milk their cows by hand. They use electrically operated milking machines. Milking machines use suction to draw the milk from the cow’s udder into a container (see Milking machine). Beef cows, which produce milk only for their calves, have smaller udders than dairy cows.

Beef cattle

Most beef cattle graze on large areas of open grassland that are unsuitable for growing crops. This method of feeding enables farmers and ranchers to raise stock without using large numbers of workers and expensive feeds and equipment. Beef cattle have been bred to produce meat under such conditions.

Beef cattle have also been bred to mature earlier than dairy cattle and to produce less milk than dairy cattle. Steers and heifers from dairy breeds also provide excellent beef, however, and contribute to the world’s meat supply.

Meat from calves that are less than 3 months old is called veal. Meat from older animals is called beef. Butchers classify beef into various cuts, such as steaks and roasts. People also eat the brains, heart, kidneys, liver, sweetbread (pancreas and thymus), tongue, and tripe (stomach lining) of cattle.

Among the most numerous breeds of beef cattle are the Aberdeen-Angus, Beefmaster, Charolais, Hereford, Limousin, and Simmental.

Aberdeen-Angus

cattle, often called simply Angus, are polled animals with black coats. These cattle mature and finish (become ready to market) at lighter weights than most other breeds. Their meat has more marbling (fat mixed with lean meat) than that of other breeds. This quality makes the cattle’s meat more flavorful. Some cattle raisers believe the breed is not large enough at maturity. A number of breeders crossbreed the Angus with certain larger breeds to produce bigger offspring.

Breeders developed the Angus in the Highlands of Northern Scotland. The Red Angus, a separate breed, was developed in the United States from red calves born to Aberdeen-Angus cattle. Except for their red color, these Angus resemble Aberdeen-Angus.

Beefmaster

cattle thrive in hot, humid climates. Beefmaster cattle have horns. They also have short hair and large body surface areas for heat loss that enable them to withstand heat and humidity. The Beefmaster breed has a fleshy hump over its shoulders. Most of these cattle are various shades of red, but some may have other colors. Breeders in the United States developed the Beefmaster by crossing Hereford, Shorthorn, and Brahman cattle.

Charolais

cattle are a large, white breed that originated in France. Commercial cattle producers seek Charolais for crossbreeding because of their great size, their heavy muscular system, and the rapid growth of Charolais calves.

Hereford

cattle have red bodies and white faces, so they often are called whitefaces. They also have white patches on their chests, flanks, lower legs, and on the switches (tips) of their tails.

This breed thrives in grasslands because they can survive wide ranges in temperature better than most larger breeds. Herefords also require less care and attention than many large breeds. The Hereford breed was developed in the county of Hereford in England.

Polled Hereford cattle are a strain (type) of Herefords. They resemble Herefords but have no horns. Polled Herefords were developed by Warren Gammon, a farmer in St. Marys, Iowa, near Des Moines, in 1900. He produced the strain by crossbreeding Herefords born without horns.

Limousin

cattle were developed in France. These golden-colored cattle can be either horned or polled. The breed has a muscular body. Breeders often use the Limousin in crossbreeding programs to enhance the muscle development of less muscular cattle.

Simmental

cattle originated in Switzerland. The breed is found in many parts of Europe, where it is raised for beef, milk, and draft (pulling loads). In the United States and other countries, the large-bodied Simmental is raised mainly for beef. The cattle range in color. They may be black and white, red and white, or fawn (light yellowish-brown) and white. The American Simmental breed has rapidly increased in numbers because of such breeding techniques as artificial insemination and embryo transfer (see Breeding).

Other beef cattle.

The Shorthorn was developed in England and became the first imported breed. Shorthorns were brought from England to the United States in 1783. The Polled Shorthorn was developed in 1889 in the United States by breeding hornless Shorthorns. Shorthorns and Polled Shorthorns are used for beef production. The Milking Shorthorn was developed from the original Shorthorn cattle by selecting and breeding the cattle for high milk production. Shorthorns may be white, red, or roan (white-red), or a combination of red and white.

Many other breeds remain popular among cattle owners. Numerous U.S. breeds were developed from Zebus, humped cattle native to India. The Brahman was developed almost entirely from Zebus, whereas the Santa Getrudis was bred from Zebus and Shorthorn cattle. Brahman cattle, in turn, were mixed with various cattle to produce still other breeds. The Brangus developed from Brahman and Angus breeds and the Simbrah from Brahman and Simmental.

Popular breeds from other countries include the Chianina, from Italy; the Gelbvieh, from Austria and Germany; and the Tarentaise, from France. Still other kinds of cattle, called composites, also contribute to the world’s beef production. These cattle, which were developed by crossing various breeds, are not considered true beef breeds.

Dairy cattle

Among the most important breeds of milk cows are the Holstein-Friesian, Jersey, Guernsey, Ayrshire, Brown, Swiss, and Milking Shorthorn. All of these breeds are considered good milk producers, but some, such as the Holstein-Friesian, produce more milk than others.

In the past, dairy cows produced less milk than they do today. Dairy farmers increased the milk output, butterfat content, and protein content by improving their cattle herds. The butterfat content is important because people use butterfat to make butter. Protein is important in human diets because it helps the body grow and maintain itself. Since the 1960’s, the average annual output of milk per cow in the United States has more than doubled.

Dairy cows normally give milk for about five or six years, but some still give it at the age of 20 or older. When these cows no longer give milk, they usually are sent to a livestock market for processing into beef. Dairy cattle breeds provide about 25 percent of our beef and veal.

Holstein-Friesian

cattle, usually called Holsteins, are identified by their black-and-white coats. Some Holsteins are nearly all black or all white in color. A few varieties are red and white. Holsteins rank as the largest dairy cattle. They have broad hips and long, deep body trunks, called barrels. Their horns slant forward and curve inward.

Holsteins rank among the most common dairy breeds in the world. Many farmers favor them because a Holstein cow produces more milk than other breeds. The milk contains less butterfat than that of other breeds, however.

Holsteins probably were developed from a strain of black-and-white cattle found in the province of Friesland in the Netherlands. Cattle raisers of the Schleswig- Holstein region of Germany also helped to develop the breed.

Jersey

cattle range in color from gray to dark fawn, or reddish-brown. Some appear almost black. The Jersey cow is the smallest of the major dairy breeds. Its broad face is unusually short from its forehead to its nostrils. The small horns curve inward.

Jersey cows produce less milk than the four other major breeds, but their milk contains the most butterfat. A thick mass of cream rises to the top of a container of Jersey milk. Jersey cattle came from the tiny British island of Jersey in the English Channel.

Guernsey

cattle are slightly larger than Jerseys. The Guernsey’s orange, fawn-colored coat is spotted with white markings. The Guernsey has a long head. A white shield often appears on its broad forehead. The horns curve upward and forward.

Guernseys produce a little more milk than Jerseys. But the rich milk of the Guernsey ranks second to that of the top-ranking Jersey in butterfat content.

Guernseys probably originated on Guernsey, an island in the English Channel. Breeders crossed cattle from two regions in northwestern France, the red brindle cattle of Normandy and the small brown-and-white cattle of Brittany.

Ayrshire

cattle are red and white or brown and white. Some are nearly all red or all white. The Ayrshire’s long, curving horns give it an impressive appearance. Its body is sturdy but somewhat lean. Production of milk from Ayrshire cattle ranks between Brown Swiss and Guernsey.

Ayrshires came from the hilly country of Ayr in southwest Scotland. They are more rugged than other breeds, and they thrive on land with many hills.

Brown Swiss

may be light brown, dark brown, or brownish-gray. A light gray stripe may run along the back. The nose, horn tips, and tail switch are black. Brown Swiss are larger than most dairy cattle. The horns slant forward and upward.

Brown Swiss milk production ranks second only to that of Holsteins. The milk is pure white, and it is rich in nonfat solids, including proteins, minerals, and lactose (milk sugar). These qualities make the milk of Brown Swiss cattle excellent for cheese.

Like the Holstein, the Brown Swiss is one of the oldest breeds of dairy cattle. It was first raised in the canton (state) of Schwyz in Switzerland.

Milking Shorthorn

cattle are white, red, or roan in color and may be either horned or polled. Milking Shorthorns grow larger than most other kinds of dairy cattle, and many cattle experts consider them to be among the hardiest of the dairy breeds. They produce about as much milk as the smaller dairy breeds. The breed was developed in England.

Other dairy cattle.

Dutch Belted cattle are black, with a wide belt of white around the middle. Their milk contains about as much butterfat as that of the Brown Swiss and Ayrshire cattle.

French Canadian cattle are a small, dark brown breed, much like the Jersey and the Guernsey. They are raised mostly in Quebec. The milk of these cows is rich in butterfat.

Kerry cattle, a black breed, originated in Ireland. They are closely related to Dexter cattle, which are small and have short legs. Dexters produce about one half Dexter offspring, one fourth Kerry-type offspring, and one fourth abnormal “bulldog” calves that die at birth.

Red Sindhi is a red, Brahman-type of cattle that originated in the province of Sindh in Pakistan. It produces more milk than the Brahman. Cattle breeders in the United States have crossed it with other breeds to develop cattle with greater resistance to high temperatures.

Dual-purpose cattle

Some cattle can be raised for beef or kept as dairy cattle. They are called dual-purpose cattle. These animals have many of the qualities of beef cattle, but they also are good milk producers. Many farmers raise dual-purpose breeds only for their meat. These breeds produce calves that grow rapidly and can be processed for veal or baby beef sooner than can some beef cattle breeds.

Dairy cattle add to our supply of beef and veal. But they are not classified as dual-purpose cattle, because they are bred and raised chiefly for the production of milk.

The most important dual-purpose breed is the Red Poll. It is a red, hornless cattle. Horned Norfolk cattle were crossed with polled Suffolk to produce Red Polls. The breed originated in the counties of Norfolk and Suffolk in England.

Breeding and care of cattle

Breeding.

Cattle breeders select and mate the best types of cattle for a special purpose, such as producing large quantities of milk or high-quality beef. Then they mate the best of the offspring until, after several generations, the cattle possess the desired qualities. In this way, beef cattle have been bred to mature earlier. They thus can be sold at a greater profit than they could if they had to be fed over a longer time. Selective breeding has increased milk output and the percentage of butterfat.

Heifers usually are mated when they are about 15 months old. A cow carries her calf in her body for nine months before she gives birth. Cows usually have one calf every year. At birth, calves may normally weigh from 50 to 100 pounds (23 to 45 kilograms). Sometimes twin calves are born. Bulls may start breeding at the age of 1 year. They are most active between 2 and 6 years of age, however.

Loading the player...Cattle: Birth of a calf

A cow cannot produce milk unless it has given birth to a calf. Such a cow is known as a “fresh” cow. After the birth of the calf, the cow usually gives milk for about 10 months. A cow that does not give milk is called a “dry cow.”

Feeding.

Feeding methods have greatly improved the production of both meat and milk. Cattle are hearty eaters. The recommended daily diet for finishing a 1-year-old beef steer includes 25 pounds (11 kilograms) of corn or sorghum silage, 14 pounds (6 kilograms) of corn or ground grain sorghum, and 1/2 pound (0.2 kilogram) of soybean meal with added vitamins and minerals. The best cattle feeders use the latest scientific methods to make their cattle gain weight rapidly and efficiently and at the lowest cost.

Certain chemicals called additives may be added to cattle feed to help the cattle grow more quickly and to make them digest food more efficiently. Cattle owners may also implant additives in the back of the animal’s ear. Some farmers and ranchers add antibiotics to cattle feed to increase their animals’ weight gains.

A farmer can increase the amount of milk and butterfat produced each year by a cow by giving the animal a proper diet. The average dairy cow eats 3 pounds (1.4 kilograms) of silage or 1 pound (0.45 kilogram) of hay a day for every 100 pounds (45 kilograms) of its body weight. In addition, a dairy cow receives 1 pound of grain or other concentrated feed for every 3 pounds of milk it produces. Both dairy and beef cattle eat large amounts of forage (coarse feed), such as corn silage and alfalfa. They turn the feed into meat and milk for people to eat and drink.

Many cattle have been poisoned by eating certain kinds of plants. Weeds that may poison cattle include locoweed, death camas, and some lupines and larkspurs. Cattle owners sometimes destroy these plants with chemicals. See Locoweed.

Diseases

cost cattle owners millions of dollars each year. The most widespread cattle illnesses infect the animal’s respiratory system and digestive system. Other diseases may affect the nervous system, reproductive organs, muscles, liver, eyes, mouth, and skin.

Respiratory diseases occur in cattle of any age. However, they usually infect young animals that are exposed to the disease during shipping, periods of extreme temperature, or other stressful circumstances. Many viruses and other organisms can cause respiratory diseases, and veterinarians generally find more than one infectious organism in the lungs of cattle with respiratory illness. Some respiratory diseases can damage the lungs and lower the animal’s resistance to other infections. Signs of respiratory disease include coughing, nasal discharge, fever, and difficulty breathing. A veterinarian can give vaccines to prevent some types of disease.

Many digestive disorders are caused by bacteria, viruses, and parasites. Infected cattle usually experience diarrhea and dehydration, which can result in death in severe cases. Cattle suffering from such disorders may eat well but still lose weight. Some animals may be infected but have no symptoms. One of the most common infectious organisms, Salmonella, infects both calves and older cattle and can cause severe diarrhea.

Two other common diseases of cattle are mastitis and bloat. Mastitis likely costs dairy farmers more money each year than any other disease. Cattle obtain this bacteria from other infected cattle or from objects in the environment. The bacteria infect a cow’s udder, making it hard, swollen, and painful. Mastitis causes a drop in milk production and quality. Antibiotics can effectively treat the disease. Practicing proper care with cattle, such as good milking techniques, may help prevent mastitis.

Bloat is a noninfectious disease in which gas swells the rumen, causing the animal to stagger and gasp for breath. Cattle may be stricken with bloat when grazing in lush pastures, especially if the grass contains a large concentration of alfalfa or clover. A change in feed when cattle are hungry also may cause them to bloat. Severe bloat may result in sudden death.

Other less common diseases also infect cattle. Anthrax is caused by a germ that is usually picked up in the soil. It produces a high fever and often stops the flow of milk. Blackleg is one of the deadliest cattle diseases. It causes lameness, convulsions, rapid swelling, and high fever. Brucellosis, also called Bang’s disease, attacks the lymph glands, udders, and reproductive organs of cows. Cattle pick up the brucellosis germ from infected feed or from other objects. Cows with brucellosis often cannot bear calves. Another illness, called foot-and-mouth disease, often results in lameness and reduces milk output. Mad cow disease is a rare but serious brain disease that causes odd behavior, difficulty walking, and eventually death. Scientists think the disease arose when cattle were fed parts of sheep infected with scrapie, a similar disease.

Parasites are also costly to the cattle industry. They can transmit diseases that reduce cattle growth and milk production, and possibly cause death. External parasites include such insects as flies, lice, and mosquitoes and such arachnids as ticks and mites. These parasites bite cattle and may eat its flesh or suck its blood, which can cause the cattle much pain. Farmers can control external parasites with insecticides (chemicals that kill insects).

Internal parasites include roundworms, tapeworms, and flukes. Farmers often have difficulty detecting cattle infected with these types of parasites. Internal parasites are also hard to eliminate. Providing proper care and medications that expel worms helps reduce the chance of cattle becoming infected.

Raising and marketing cattle

Most beef calves are born in the spring. The young calves spend the summer with cows in fenced pastures, or on an open range. Most calves are branded (marked) with a hot iron to show their ownership. In the fall, the calves are weaned (taken from their mothers).

Feeder cattle.

The farmer or rancher sells the weaned calves to farmers called feeders. Such calves, known as feeder cattle, are raised in feed lots. A feed lot is an enclosed area where cattle receive special feed to finish them for market. The farmer then sends them to a meat-packing plant for processing. See Meat packing.

Ranchers and farmers sometimes send their calves directly to a market instead of selling them to feeders. Farmers, in turn, may buy feeder cattle from a carefully chosen market instead of from a rancher. The farmers feed such calves to a desired weight for market and then sell them to a meat-packing plant at a profit.

A farmer usually feeds feeder cattle for 120 to 240 days. The farmer tries to sell them when market conditions offer the largest profit. A steer is normally ready for processing by the time it reaches 15 to 20 months of age. Cattle grow to their full size in 2 to 3 years. Many cattle are heavy enough to sell before they reach maturity, however.

Some farmers in the East and Midwest breed and raise their own cattle. But most farmers find it more profitable to buy feeder cattle and use their land for growing corn and other livestock feed to give the stock.

Grass-fed cattle.

Cattle owners sometimes feed their stock on grass for one or two years, and sell the animals as “grass fattened.” Some grass-fattened cattle also receive grain feed for several weeks before they are finished. Farmers in southern coastal areas raise many calves that are sold for early processing or for grazing on richer pastures. Their land is not suitable for raising feeds on which to finish cattle.

Dairy cows.

Most dairy cows spend their lives on one farm. Heifers from cows that have produced little milk are sent to market to be processed for veal when only a few weeks old. It is probable that such calves, like their mothers, would be poor milk producers. Most male calves also are sent to market. Dairy farmers save the female calves of the best cows for herd replacements. When a cow fails to produce milk economically, it is sent to a livestock market and sold for processing. Such dairy cows produce much of the world’s low-grade beef.

Show cattle.

Cattle owners exhibit prize animals at local and regional fairs and livestock expositions. A champion dairy cow has a large body, a strong set of feet and legs, and a well-developed udder. In the United States, a blue-ribbon beef animal has a solid, compact body with a rectangular shape. Exhibitors, such as 4-H Club members, start developing show cattle as soon as the calves are weaned. They carefully feed, exercise, and groom the animals.

Nomadic cattle raising.

In some parts of the world, farmers still follow the ancient practice of _nomadic cattle raising—_moving with herds of cattle in search of grazing and water. An example is the Maasai people of Kenya. The herds of cattle maintained by nomadic people can be extremely large. Because cattle are a sign of wealth, the people usually consider the quantity of animals more important than their quality.

History

Early cattle.

Modern breeds developed from the early domestic cattle of Europe and Asia. Some scientists consider each group to be a distinct species. Others believe both types are only one species. Both groups descended from the aurochs, or wild oxen, that once roamed Asia, Europe, and northern Africa. The last aurochs died in Poland in 1627.

People have raised cattle for thousands of years. Pictures carved in ancient Egyptian tombs show oxen pulling plows and treading grain.

Cattle raisers once followed their herds from land to land as the cattle searched for grass to eat. Later, some of these herders and their families settled in one place. They fed their cattle grain in addition to grass.

Beginning of breeding.

The first cattle were used as work animals as well as for producing milk and beef. Gradually, people began to breed cattle either as beef animals or for producing milk. Robert Bakewell, a farmer in Leicestershire, England, was the first person to use modern livestock breeding methods. He began improving his cattle in the late 1700’s. He used a breed of cattle called Longhorns (different from Texas longhorns) and tried to develop cattle that would give larger amounts of meat.

American cattle.

Some historians believe that cattle were first brought to the Americas by Norwegian Vikings in the early 1000’s. In 1493, the Italian explorer Christopher Columbus brought long-horned cattle from Spain to Santo Domingo (now the Dominican Republic) on his second voyage to America. Descendants of these cattle later were taken into Mexico and eventually into Texas. They were ancestors of the famous Texas longhorns.

Governor Edward Winslow of Plymouth Colony brought cattle to New England in 1624. Cattle raising spread westward as the pioneers moved across the continent. The pioneers used oxen to pull wagons and plows.

Railroads helped cattle ranchers on the plains by providing transportation to the eastern markets. Refrigerated railroad cars made it possible to ship meat products safely over long distances. Breeders’ organizations encouraged the improvement of beef and dairy cattle. Livestock shows spurred interest in breeding prizewinning cattle.

In the West, ranchers came to realize that the Texas longhorn grew more slowly and was less profitable than such breeds as the Hereford and Aberdeen-Angus. The longhorn produced little beef in proportion to its bulk. By the 1920’s, the Texas longhorn had nearly disappeared from the Western ranges. The number of Texas longhorns began to increase again during the 1970’s, however. Today, a few farmers and ranchers use longhorns chiefly for crossbreeding with other breeds of cattle.

The world supply.

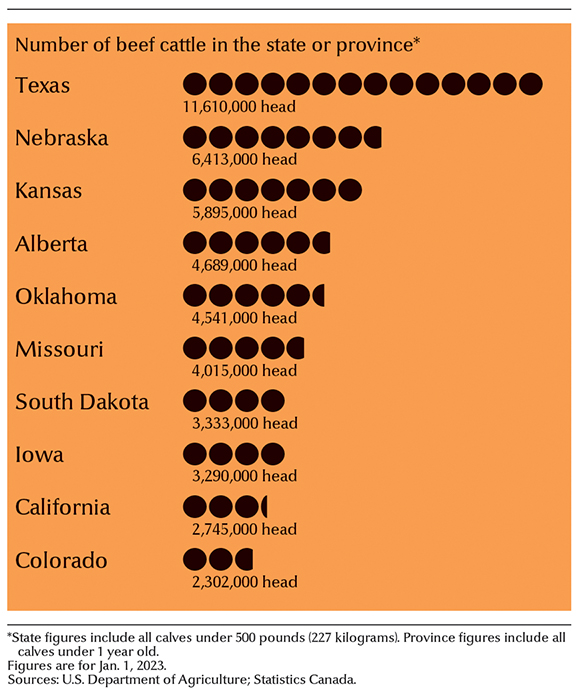

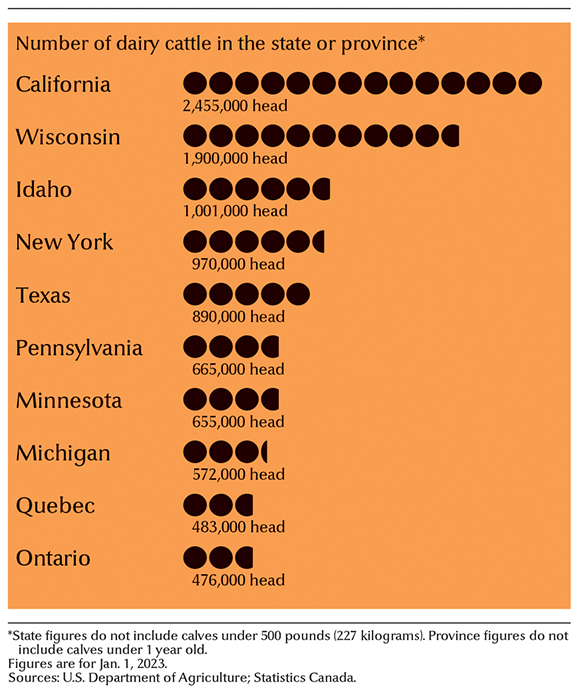

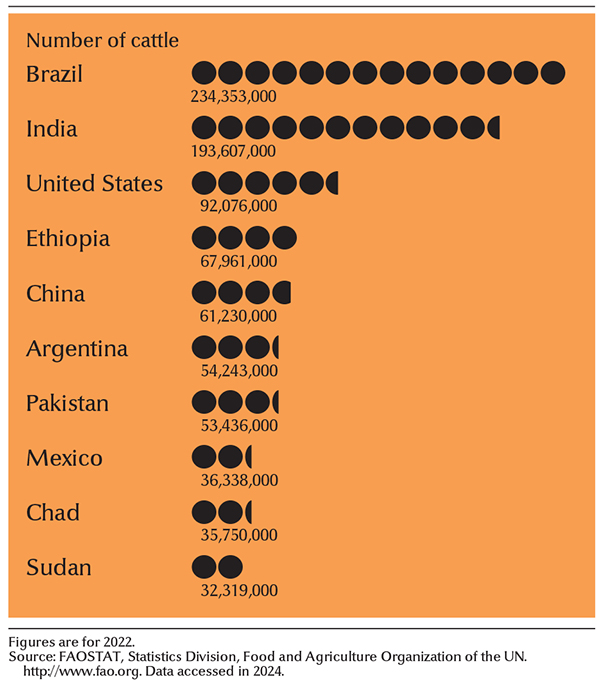

There are about 11/2 billion beef and dairy cattle worldwide. Asia raises about one-third of the world’s cattle. South America ranks second among the continents in the number of existing cattle.

Brazil and India are the leading cattle-raising countries. But India’s cattle are undernourished and have little work value. There is also little demand for meat in India because Hindus consider the cow sacred. Argentina, China, Ethiopia, and the United States rank among the largest producers of beef and dairy cattle. Cattle farmers in many countries work to improve their breeds and to increase beef and milk production.