Cheese is a food made from milk. For thousands of years, cheese has been an important food in a variety of cultures. Cheese can be eaten alone or it can be served on crackers, in sandwiches, in salads, and in cooked foods, such as pizza.

There are hundreds of kinds of cheeses, and they differ in taste, texture, and appearance. Many cheeses spread easily, but others are hard and crumbly. Some kinds of cheeses taste sweet, and others have a sharp or spicy taste.

Cheese stays fresh longer than milk, and it has much of milk’s food value, including proteins, minerals, and vitamins. Cheese contains these nutrients of milk in concentrated form. For example, 8 ounces (227 grams) of Cheddar cheese provide as much protein and calcium as 11/2 quarts (1.4 liters) of milk. Cheese supplies important amounts of vitamin A and riboflavin.

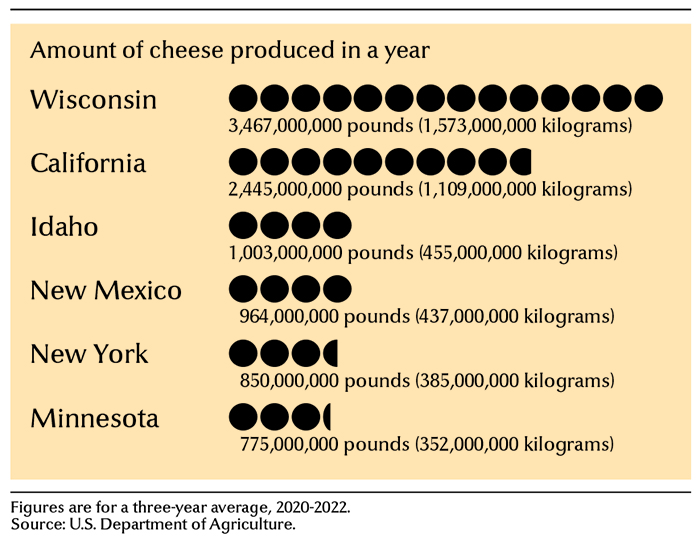

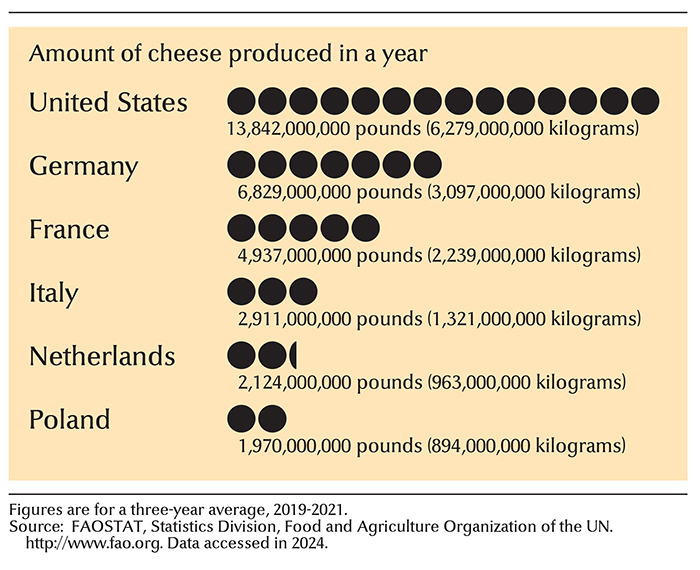

The United States leads the world in cheese production. Almost every state of the United States makes some cheese. Wisconsin and California are the leading cheese-producing states. Together, they account for about half of U.S. cheese production. The U.S. Department of Agriculture grades a large quantity of the cheese produced in the United States as AA, A, B, or C. In addition, some states have their own standards for grading cheese. Most cheese made in Canada comes from the provinces of Quebec and Ontario. The Canadian government has its own standards for grading cheese produced in that country.

Most cheese is produced from cow’s milk. People in Europe and Asia frequently make cheese from the milk of such animals as buffaloes, goats, and sheep. But cheese can be made from the milk of any animal. Herders in Lapland use reindeer milk in making cheese. In Tibet, yaks supply milk for cheese. Cheese has also been made from the milk of camels, donkeys, horses, and zebras.

Kinds of cheese

There are hundreds of kinds of cheese. Some cheeses are known by two or more names. For example, Emmentaler cheese is also called Swiss cheese. Many cheeses take their names from the country or region where they were first produced. Emmentaler cheese originally came from the Emme valley in Switzerland, and Roquefort cheese is made only near Roquefort, France.

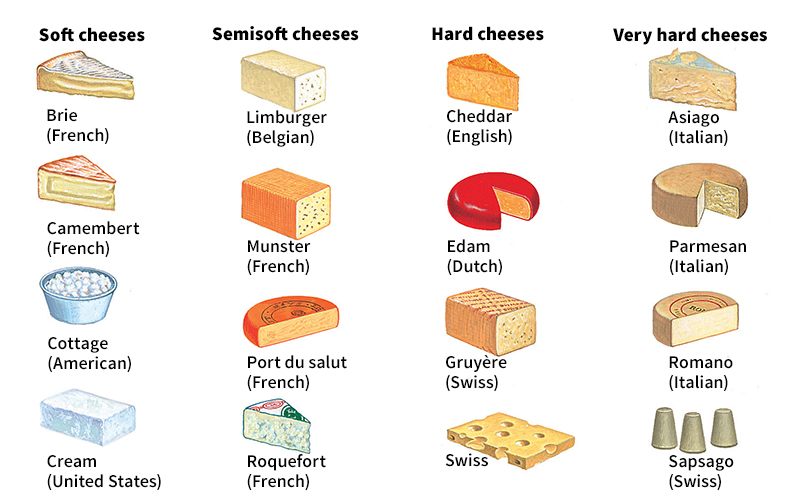

Almost all cheeses belong to one of four main groups: (1) soft, (2) semisoft, (3) hard, and (4) very hard, or grating. The amount of moisture in the cheese determines its classification. The more moisture the cheese contains, the softer it is.

Soft cheese.

Cottage cheese and cream cheese are two of the most popular soft cheeses. Some soft cheeses, including Brie and Camembert, develop a crust. A desirable mold growth causes the crust to form, releases enzymes, and changes the acidity of the curd, which in turn softens the cheese and develops its flavor.

Semisoft cheese

includes such varieties as blue, brick, Limburger, Monterey Jack, mozzarella, Munster, Port du Salut, Roquefort, and Stilton. Blue, Roquefort, and Stilton cheese have streaks of blue mold running through them. The mold, which is added during the cheesemaking process, gives these cheeses a special flavor. Blue and Stilton are made with cow’s milk, but Roquefort is made only from sheep’s milk.

Hard cheese.

Cheddar, Edam, Gruyere, and Swiss are popular varieties of hard cheese. Gruyere and Swiss cheese have holes called eyes. Cheese makers form the eyes by adding bacteria that produce bubbles of carbon dioxide gas in the cheese during storage. When the cheese is sliced, the bubbles become holes.

Very hard, or grating, cheese

includes Asiago, Parmesan, Romano, and sapsago. People usually grind such cheeses and sprinkle them over such foods as soups, vegetables, pasta, and pizza.

How cheese is made

Almost all the cheese produced in the United States is made in large factories. The process used involves five basic steps: (1) processing the milk; (2) separating the curd; (3) treating the curd; (4) ripening; and (5) packaging. Slight differences in the process result in the production of several hundred varieties of cheese.

Processing the milk.

Cheese makers inspect the milk and remove any solid substances by a process called clarification. The milk flows into a pasteurizer that kills harmful bacteria. Pumps force the pasteurized milk into metal tanks or vats that hold from 8,000 to 35,000 pounds (3,600 to 15,900 kilograms). About 10,000 pounds (4,535 kilograms) of milk are used to make 1,000 pounds (450 kilograms) of cheddar cheese.

Separating the curd.

After the milk has been processed, it is treated to form a soft, custardlike substance called curd. The curd contains a liquid called whey, which must be expelled before cheese can be made. Cheese makers form the curd by first heating the milk to 86° to 96 °F. (30° to 36 °C). Then they add a liquid called a starter culture to the milk. This liquid contains bacteria that form acids and turn milk sour. Vegetable dye may also be added to give the cheese a certain color. At the start of the souring process, mechanical paddles stir the starter culture and dye evenly through the milk.

After 15 to 90 minutes, workers add an enzyme that causes the milk to thicken. Cheese makers have long used rennet, a substance from the lining of the stomachs of calves. But a shortage of such rennet has caused them to use other enzymes, including rennets produced by molds. They also use genetically engineered bacteria to produce the rennet enzyme historically made in the stomachs of calves (see Genetic engineering ). The paddles blend the enzymes into the milk, which is then left undisturbed for about 30 minutes so curd will form.

Special knives cut the curd into thousands of small cubes, and the whey oozes from them. The paddles stir the curd and whey, and the temperature in the vat is raised to between 102 °F. (39 °C) and 130 °F. (54 °C), depending on the type of cheese. The motion and heat force more whey from the curd. The whey is then drained or the curd is lifted from the vat.

Treating the curd.

In making most cheeses, the curd is left undisturbed after the whey is drained off. The particles stick together and form a solid mass. The curd is then broken up into small pieces for pressing. To make cottage cheese, workers rinse the curd with water and mix it with cream and salt.

The curd for Cheddar goes through a special step after being formed into a solid mass. Workers cut the curd into large slabs, stack them in the vat, and turn them every 10 minutes. This process, called cheddaring, may also be done mechanically in large towers, rotating cylinders, or steel boxes. The slabs of curd pass through a mill, which chops them into small pieces.

The curd for most cheeses is packed into metal hoops or molds for pressing. The containers are put into presses that keep the cheese under great pressure for a few hours to a few days. During pressing, more whey drains and the curd is shaped into blocks or wheels. Most cheeses are salted after pressing. But Cheddar and some other cheeses are salted before pressing.

After pressing, workers remove the cheese from the hoops or molds. A crust called a rind begins to form on the cheese as it dries. To prevent a rind from forming most cheeses are sealed in plastic wrap immediately after they are removed from the metal hoops. Most cheeses today are rindless.

Ripening,

also called aging or curing, helps give cheese its flavor and texture. Cheese is aged in storage rooms or warehouses that have a controlled temperature and humidity. Aging times vary for different cheeses. Brick cheese and others need two months to age. Parmesan requires about a year. The longer the curing time, the sharper the cheese’s flavor.

Packaging.

After being aged, cheese is packaged in a wide variety of shapes and sizes. Some cheeses are sliced at the factory and sealed in foil or plastic. Others are sold whole–in large blocks, wedges, balls called rounds, or short cylinders called wheels.

Process cheese

Much of the cheese produced in the United States is made into process cheese, a blend of natural cheeses. Process cheese keeps better than natural cheeses, and it melts more evenly and with less free oil when used in cooking. Some process cheese is made from two or more kinds of cheese. Other process cheese is a mixture of batches of the same kind of cheese that differ in taste and texture. The cheeses are ground up and then blended with the aid of heat and chemicals called emulsifier salts. Process cheese made from only one variety of cheese is named for that cheese. For example, process Swiss cheese is made only from Swiss. However, process cheese labeled Pasteurized Process American Cheese may be made from a combination of cheeses, including Cheddar, Colby, and washed curd cheese. In the United States, labels must identify all cheeses used in process cheese made from two or more kinds of cheese.

Process cheese foods and process cheese spreads are made like process cheese. But cream, milk, or whey are added to make them more moist. Fruit, meat, spices, or vegetables may be added for extra flavor. Cold-pack cheese is a blend of natural cheeses. Its manufacturing process involves no heat. Much cold-pack cheese includes meat or wine as flavoring.

History

Historians are not sure when and where cheese was first made. By around 6000 to 5000 B.C., people in parts of Asia and Europe were probably making cheese.

Cheese making began in the American Colonies in 1611. That year, settlers in Jamestown, in the Virginia Colony, imported cows from England. In 1851, an American dairyman named Jesse Williams established the nation’s first cheese factory, near Rome, New York.

In 1916, J. L. Kraft, an American businessman, patented a method for making process cheese. His Kraft company also developed a method for wrapping individual slices of cheese mechanically.

During the 1970’s, scientists developed methods of removing proteins and lactose (milk sugar) from whey. Most whey had previously been thrown away. Today, manufacturers add these nutritious substances from whey to baby food, bread, ice cream, and other foods.

Also during the 1970’s, European cheese makers began to use a process called ultrafiltration for making soft cheeses. In this process, the milk is strained through such a fine filter that only water, lactose, and salts are lost. The remaining liquid contains most of the proteins normally drained off with the whey. By concentrating the milk mixture so highly, ultrafiltration makes it possible to produce more cheese in a vat. The process was first used commercially in the United States in the mid-1980’s.

See also Casein .