Alfalfa, also called lucerne, is a cloverlike plant grown mainly for forage (livestock feed). Livestock producers feed alfalfa to cattle, horses, sheep, and other animals. Alfalfa is sometimes called the “queen of the forages.” Alfalfa produces an abundant harvest and is high in nutrient quality. It provides energy, protein, and minerals that promote rapid growth and good health in animals. Farmers harvest alfalfa as hay. They also make silage (feed stored in silos) and alfalfa cubes or pellets. In addition, farmers grow alfalfa for grazing and for its seeds. Planting alfalfa benefits the environment by enriching the soil with nitrogen and protecting it from erosion.

The United States ranks as the world’s leading alfalfa grower. It raises about 60 million tons (54 million metric tons) of alfalfa each year. The leading alfalfa-growing states include California, Idaho, Montana, Nebraska, South Dakota, and Wisconsin. Other major alfalfa producers include Argentina, Canada, China, Italy, and Russia. The leading alfalfa-growing provinces in Canada are Alberta, Manitoba, Ontario, and Saskatchewan.

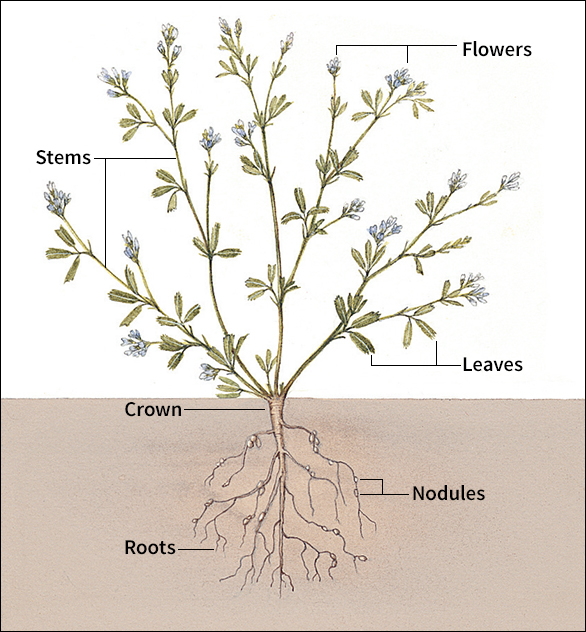

The alfalfa plant

Alfalfa is a perennial—that is, it grows from year to year without being replanted. It can live as long as 25 years, but a typical lifespan is 4 to 7 years. The alfalfa plant is a legume, a member of the pea family.

The alfalfa plant produces many slender stems. The stems regrow readily after cutting. They reach up to about 3 feet (1 meter) high and bear compound leaves, each consisting of three leaflets. New stems grow from buds on the plant’s woody crown. The crown is an enlarged portion of the top of the roots. Alfalfa leaves and stems are usually harvested after about four or five weeks of growth. They are used for livestock feed.

Flowers grow on the stems in clusters called racemes. Each raceme consists of 5 to 50 flowers. Most alfalfa flowers are purple, but some are green, white, yellow, or variegated (multicolored).

Alfalfa has a deep taproot (long main root). Alfalfa roots can reach as deep as 15 feet (4.6 meters) or more. These deep roots can reach water and nutrients far belowground. For this reason, alfalfa plants have a greater resistance to drought than do many other crops. Beneficial bacteria called Rhizobium live in the roots of alfalfa. These bacteria absorb nitrogen from the air. They fix the nitrogen—that is, they convert nitrogen gas from the air into nitrogen compounds that the plant can use.

Uses of alfalfa

As livestock feed.

Most alfalfa grown in the United States is baled as hay or preserved as silage. Livestock may also graze directly on alfalfa or eat it freshly cut. Dairy cattle eat more than 75 percent of alfalfa. Farmers also feed alfalfa to beef cattle, goats, horses, and sheep. Alfalfa thus aids in the production of a variety of goods, including cheese, milk, yogurt, meat, and wool. Bees that feed on alfalfa nectar produce honey.

Alfalfa hay is typically stored in bales. Small rectangular bales weigh from 50 to 150 pounds (23 to 68 kilograms). Large rectangular bales weigh from 1,200 to 2,000 pounds (540 to 900 kilograms). Round bales weigh as much as 2,000 pounds (900 kilograms).

To make hay, farmers swath (cut) the alfalfa, rake it, and let the sun dry the plants. At the time alfalfa is cut, it contains 70 to 80 percent moisture. Before being baled, the plants should contain less than 15 percent moisture. Hay that is too dry when baled will lose its nutritious leaves. Hay that is too wet will mold. See Hay .

Hay can be used to feed livestock on the farm. It also may be sold to other farmers or ranchers. Hay and other alfalfa products are exported by Canada and the United States to Japan, South Korea, and the Middle East.

Some alfalfa is stored as silage. Farmers in wet areas often use silos during the spring, when the weather is unsuitable for drying hay. Silage can be preserved for many months. The key advantage of silage is that a farmer can harvest the crop more quickly. A quick harvest reduces the chance that the crop will be damaged by wet weather. See Silo .

Some alfalfa is preserved in the form of thickly packed cubes or pellets. Alfalfa cubes are often used to feed horses. Pellets are commonly used to feed such pets as gerbils and rabbits. Poultry farmers often add alfalfa pellets to poultry feed. This practice helps to produce high-quality eggs and meat.

Farmers may plant alfalfa mixed with grass for grazing, especially in rainy areas with poor drainage. Growers graze their livestock for about a week. They then allow the alfalfa plants to grow back for about four weeks. This method of feeding livestock is called rotational grazing. Alfalfa grazing is uncommon in North America, but it is common in Argentina and other countries.

As a cover and rotation crop.

Some farmers use alfalfa as a cover crop. A cover crop enriches the soil and protects it from erosion. Rhizobium bacteria living in nodules (swellings) on alfalfa roots fix nitrogen from the air. Like other plants, alfalfa needs nitrogen to grow. In exchange, the plant provides food to the bacteria. This relationship is an example of symbiosis. Symbiosis is an arrangement in which organisms live together in a way that benefits one or more of them. Alfalfa plants enrich the soil by adding more nitrogen to it than they use.

Farmers often alternate growing alfalfa with other crops. This practice is known as crop rotation. Corn or grain crops that cannot fix nitrogen may require less chemical fertilizer in fields where alfalfa has grown. In addition, diseases and pests that thrive on one crop may not thrive on others. By rotating crops, farmers can help to control diseases and pests.

As a seed crop.

A small amount of alfalfa is grown for its seeds. Seeds are sold to farmers who grow alfalfa for livestock feed. Alfalfa cultivated for seed requires dry weather for harvesting. The seeds develop only if the flowers have been pollinated by bees. In the United States, most pollination is carried out by commercial beekeepers, who carry their bees from farm to farm.

As food for people.

People consume alfalfa sprouts, alfalfa supplements, and alfalfa juice. But people directly consume only a relatively small amount of alfalfa.

Kinds of alfalfa

Farmers grow hundreds of varieties of alfalfa. Each variety is adapted to a particular kind of climate. Breeders develop varieties to improve such traits as yield, winter hardiness, resistance to disease and pests, persistence, and forage quality, among others.

As perennials, most alfalfa plants slow their growth in the fall to prepare for winter, a trait known as fall dormancy (inactivity). They resume growth in the spring. Alfalfa varieties differ in their degree of fall dormancy. They also differ in how well they withstand winter weather conditions. Alfalfa varieties with the greatest degree of fall dormancy and winter hardiness can be grown in such places as Canada, Wisconsin, and Minnesota. Varieties that do not become dormant are grown under irrigation in the southwestern United States, Mexico, and warm areas around the world.

Breeders have developed alfalfa varieties with resistance to a wide range of diseases, insects, and other pests. Alfalfa may have a wider resistance to pests and diseases than any other cultivated crop plant. This resistance reduces the need to use artificial chemicals.

Growing alfalfa

Alfalfa plants flourish in fertile, well-drained soil that is slightly alkaline (acid-neutralizing) or neutral (neither acidic nor alkaline). In dry regions, alfalfa needs irrigation for successful growth. Before planting alfalfa, farmers may prepare the soil by applying fertilizers, herbicides, or other chemicals. Farmers plant alfalfa seeds 1/4 to 1/2 inch (6 to 13 millimeters) or less below the surface.

Farmers plant alfalfa in early spring to late summer or fall, depending upon the region. They harvest a new crop every four to six weeks. Harvests are timed after flower buds form but before significant flowering. Farmers must harvest at just the right time to maximize the amount and quality of the forage. Alfalfa is harvested from 2 to 4 times a year in northern climates. It is harvested from 5 to 11 times a year in the Mediterranean and desert regions of Argentina, Australia, the United States, Mexico, and the Middle East.

Diseases and pests.

A number of diseases and pests damage alfalfa crops. The diseases include anthracnose, bacterial wilt, Phytopthora root rot, leaf spot, and spring blackstem. All of these diseases are caused by bacteria or fungi. Crown rot and root rot severely damage alfalfa that has been injured by cold weather, field traffic, insects, or poor harvesting methods (see Rot ). Leaf diseases harm alfalfa by causing the leaves to drop off.

Weeds

use up nutrients and water that alfalfa plants need. They also shade the plants, blocking the sunlight plants need to grow. Weeds in the forage also reduce its quality. Some poisonous weeds can sicken or even kill livestock. Farmers often control weeds through the use of herbicides (weed-killing chemicals).

Insect pests

that attack alfalfa include alfalfa weevils, potato leafhoppers, and aphids. Larval (young) alfalfa weevils eat alfalfa leaves, reducing the yield and quality of the hay. Potato leafhoppers and aphids suck juices from alfalfa stems. This damage hinders the growth of the plants. Some nematodes (microscopic roundworms) also damage alfalfa. Farmers may use insecticides to control insect pests.

Beneficial insects.

Alfalfa is known as an insectary because it supports many beneficial insects. Such helpful insects include ladybugs and various wasps. They attack and kill such pests as aphids and worms. Farmers may grow strips of alfalfa near other crops to promote beneficial insects.

Organic alfalfa,

like other organic crops, is grown using little or no pesticides, synthetic fertilizers, or other artificial chemicals. Alfalfa is often used in farms making a transition from conventional to organic agriculture. Alfalfa provides many benefits to organic farms. It improves the soil structure and enriches the soil with nitrogen. It also supports beneficial insects. Certified organic dairy or beef production requires some grazing. For this reason, organic alfalfa may be grazed rather than cut. Such grazing helps to control weeds. Organic alfalfa makes up a small but expanding part of overall alfalfa production in the United States.

History

Alfalfa was one of the earliest crops grown by human beings. It probably originated in the region between the Middle East and the Caucasus, a region that includes Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia. Records on brick tablets found in Turkey indicate that alfalfa was an important feed for cattle in that region by 1400 B.C. It was brought to Greece by 490 B.C. Later, it was introduced to northern Africa and present-day Italy and Spain.

During the A.D. 1500’s, Portuguese and Spanish explorers brought alfalfa to Central and South America and to what is now the southwestern United States. Settlers brought alfalfa from Europe to the American Colonies. There, it was grown by George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, among others. However, it did not grow well in the East because of the acidic soils along the Atlantic Coast. Alfalfa did not become widely grown in the United States until after 1850. At that time, a variety called Chilean clover was brought to California from Chile. California farmers grew it successfully under irrigation. Alfalfa farming then spread rapidly through the West. In 1900, nearly all alfalfa production in the United States took place west of the Mississippi River. About that time, new varieties of alfalfa were brought from cold climates in Europe and Asia. These varieties grew well in the upper Midwest and Northeast.