Civil War, American (1861-1865), took more American lives than any other war in history. It so divided the people of the United States that in some families brother fought against brother. The war’s terrible bloodshed left a heritage of grief and bitterness.

The war was a conflict between the United States government and a group of states that had seceded (withdrawn) from the union. The Southern States had broken away to form the Confederate States of America. The U.S. government sought to maintain the union, insisting that states were not permitted to secede. The issue behind secession was slavery. The South’s economy relied heavily on the labor of enslaved African Americans. Southerners feared the federal government would try to limit or end slavery.

Loading the player...Abraham Lincoln

The American Civil War is also known by such names as the War Between the States and the War of Secession. The opposing sides were known as the Union, or the North, and the Confederacy, or the South. The Union soldiers were called Yankees, a nickname originally applied to the New England colonists. The Confederates were the Rebs, for rebels.

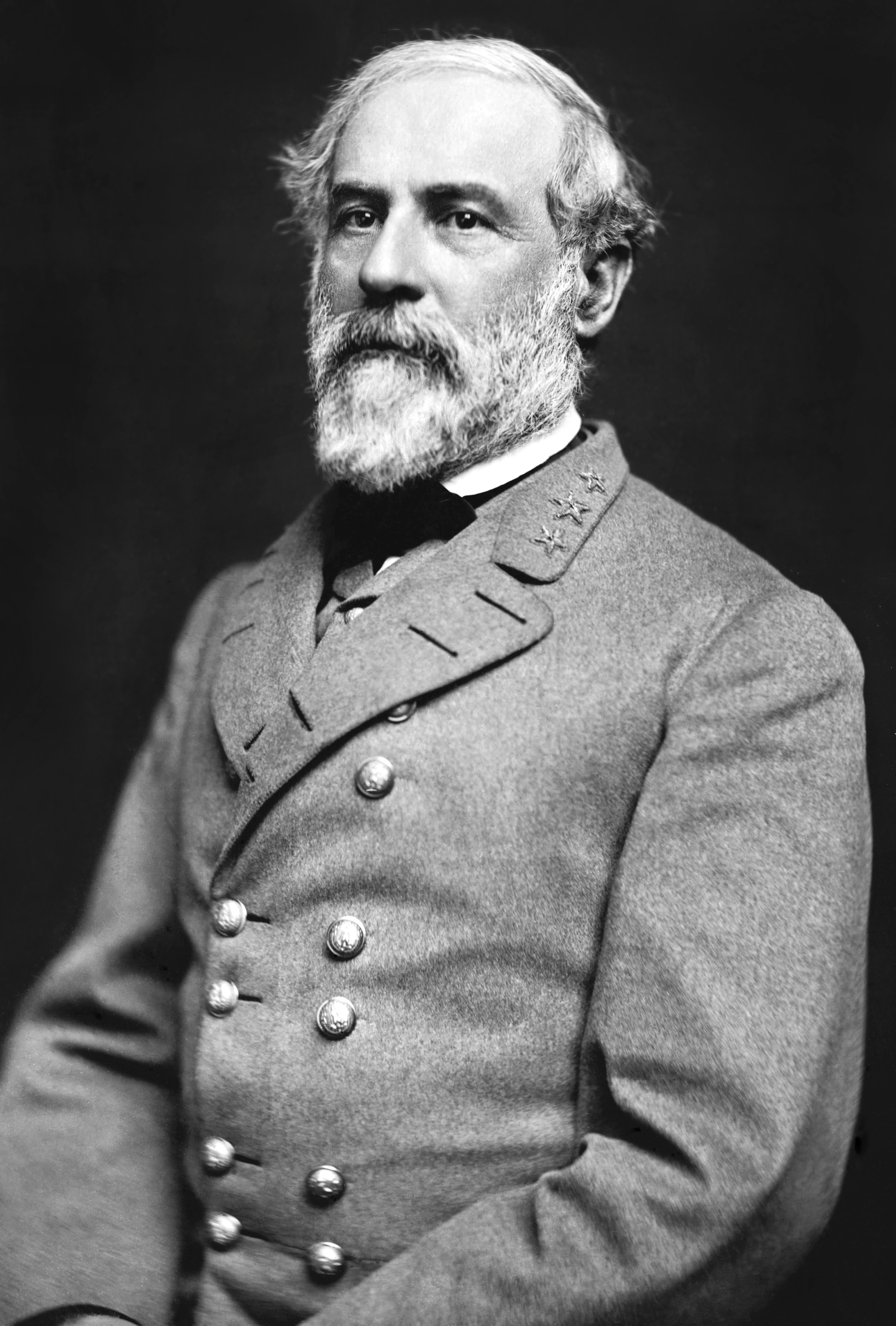

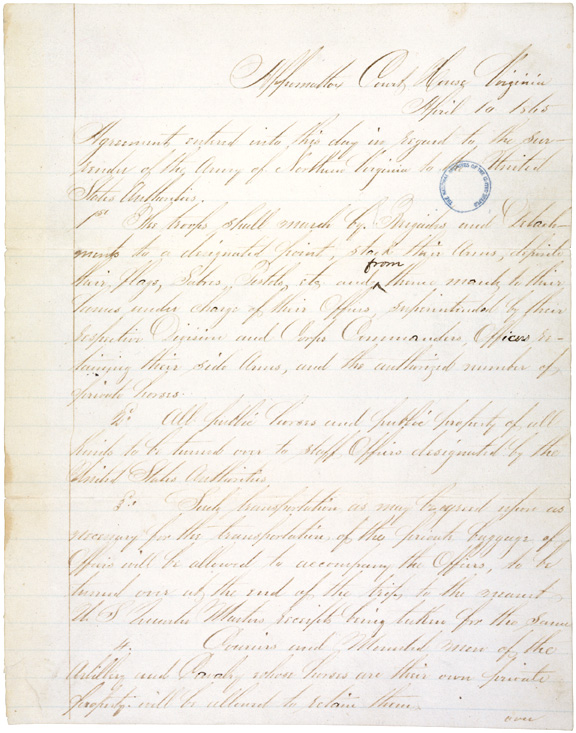

The war started on April 12, 1861, when Confederate troops fired on Fort Sumter, a U.S. military post in Charleston, South Carolina. It ended four years later. On April 9, 1865, Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered his army to Union General Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Court House, a small Virginia settlement. The other Confederate forces gave up soon after.

Over the years, the war has been the subject of numerous books, plays, movies, television programs, paintings, and sculptures. Civil War monuments stand in parks and squares throughout the United States. Battlefields and the tombs and former homes of such people as U.S. President Abraham Lincoln, Confederate President Jefferson Davis, and Generals Lee and Grant are popular tourist sites. Some Civil War figures are among the nation’s most beloved heroes. Lincoln in particular became a respected figure throughout the world.

Causes and background of the war

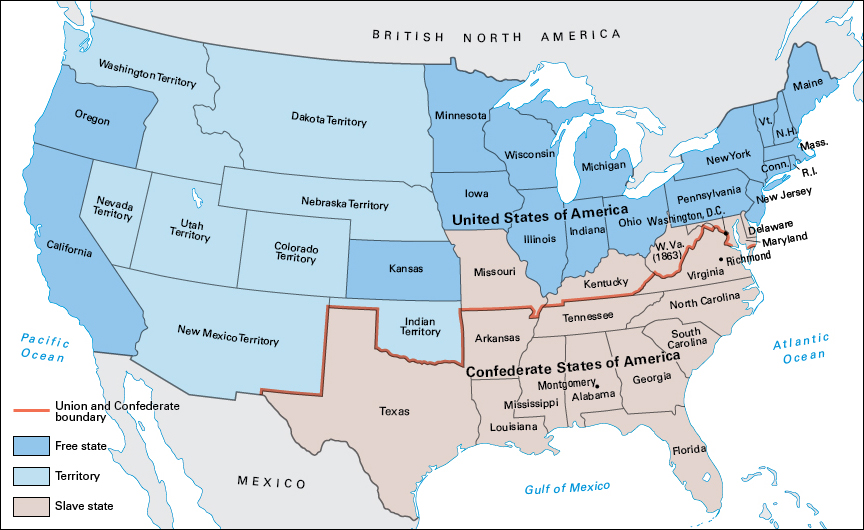

In 1861, the United States consisted of 19 free states, in which slavery was prohibited, and 15 slave states, in which it was allowed. U.S. President Abraham Lincoln called the nation “a house divided.” Americans had much in common, but the free and slave states also had many basic differences besides slavery.

Historians have long debated the causes of the Civil War. Many of them maintain that slavery was the root cause. In his second inaugural address in 1865, Lincoln said of slavery: “All knew that this interest was, somehow, the cause of the war.” But most historians agree that the war had a number of causes. They note, for example, that the northern and southern states had been drifting apart because of sectional differences, dissimilarities between the two areas in culture and economy. They also point to ongoing tensions between the federal government and the states over the extent of the federal government’s powers. They mention the disorder in the American political party system of the 1850’s. Yet slavery emerges as the most serious single cause. All explanations for the causes of the war have always involved or revolved around that issue.

Sectional differences

Sectional differences between North and South dated from colonial times. The settlers of the South had found the warm climate and long growing season ideal for raising tobacco and, later, cotton. But these crops required intense labor to plant, maintain, and harvest. The Southerners did not have enough people to do the work. They turned to slave labor. European slave traders shipped millions of captive Africans to the Americas from 1500 to 1860. By 1860, about 4 million enslaved Black people labored in the Southern States.

In the North, slave labor was used until the 1800’s. But the cooler climate and shorter growing season discouraged the development of such crops as tobacco or cotton. Most Northerners earned their living by farming. But the North had no plantations and no need for farm labor on such a large scale as in the South. Immigrants from Europe poured into the North’s great port cities of New York, Philadelphia, and Boston. Northern farmers found it less expensive to hire immigrant workers than to buy enslaved people.

Unlike the South, the North rapidly developed a manufacturing economy. The extent of Northern manufacturing helped create an environment in which the normal concept of labor was that of free workers hiring themselves out for wages rather than enslaved people working because they were forced to do so.

The North also was home to strong Protestant religious and cultural forces. Northern Protestants highly valued moral strictness, economic independence, and efforts to improve oneself. They disapproved of slavery and believed it to be an embarrassment to a republic dedicated to liberty and freedom.

The conflict over slavery

In colonial times, most Americans regarded slavery as a necessary evil. The Founding Fathers of the United States had been unable to abolish slavery and compromised over it in writing the Constitution (see Constitution of the United States (The compromises) ).

By the early 1800’s, many Northerners had come to view slavery as wrong. Abolitionists in the North began a movement to end it. An antislavery minority also existed in the South. But most Southerners found slavery to be highly profitable and in time came to consider it a positive good. From a fourth to a third of all Southern white people were members of slaveholding families. About half the families owned fewer than 5 enslaved people, though less than 1 percent of the families owned 100 or more. Even many of the white Southerners who did not own slaves supported slavery. They accepted the ideas that the South’s economy would collapse without slavery and that Black people were inferior to white people.

In 1858, Senator William H. Seward of New York, who later became Lincoln’s secretary of state, referred to the differences between North and South as “an irrepressible conflict.” He placed slavery at the heart of that uncontrollable conflict. Indeed, an almost continuous series of debates over slavery raged in Congress between Northern and Southern lawmakers during the 1850’s.

The Compromise of 1850

was a group of acts passed by Congress in the hope of settling the slavery question by giving some satisfaction to both the North and the South. The Compromise allowed slavery to continue but prohibited the slave trade in Washington, D.C. It admitted California to the Union as a free state but gave newly acquired territories the right to decide for themselves whether to permit slavery. The Compromise also included a strict fugitive slave law that required Northerners to return enslaved people who had escaped to their owners.

Northerners resisted the fugitive slave law in several ways. Abolitionists disobeyed the law by operating the underground railroad, a system of escape routes and housing for enslaved people who had run away. The routes led from the slave states to the free states and Canada. Abolitionists also rescued or tried to rescue fugitives after they had been recovered in the North by their owners. A number of rescue attempts, such as those in Christiana, Pennsylvania, in 1851 and in Boston in 1854, resulted in riots and several deaths. One of the most effective attacks on the fugitive slave law—and on slavery as a whole—was Harriet Beecher Stowe’s best-selling antislavery novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1851-1852).

The Kansas-Nebraska Act

was passed by Congress in 1854. Like the Compromise of 1850, it dealt with the problem of slavery in newly formed territories. The act created the territories of Kansas and Nebraska and gave the people of these territories the right to regulate matters related to slavery. It also provided that before the territories became states, the people of each territory could decide whether to allow slavery in the new states. The decision process was called popular sovereignty. Many Northerners opposed the act. They feared that once slavery was in a territory, it was there to stay.

The first test of popular sovereignty came in Kansas, where a majority of the population voted against becoming a slave state. But proslavery forces refused to accept the decision. The situation quickly erupted into violence. The violence spread to Washington, D.C., where in 1856 an antislavery senator, Charles Sumner of Massachusetts, was beaten unconscious by Preston Brooks, a proslavery representative from South Carolina. In the end, Kansas joined the Union as a free state in 1861.

The Dred Scott Decision.

In 1857, the Supreme Court of the United States tried to settle the slavery issue through the decision it handed down in the case involving Dred Scott. Scott, an enslaved Black man from Missouri, sued for his freedom. He and his master had moved from Missouri to a state that did not allow slavery, and later to a territory that also did not allow slavery. Scott said that he had become a free man by living in areas where slavery was not recognized.

Chief Justice Roger B. Taney wrote the majority decision. He said that Scott, as a Black man, was not a citizen, and therefore did not have the right to sue in a U.S. court. Taney also said that the federal government could not exclude slavery from the territories. The decision angered many Northerners. They believed it opened all the territories to the expansion of slavery. They also felt it was an attempt to close off any further debate about slavery in Congress.

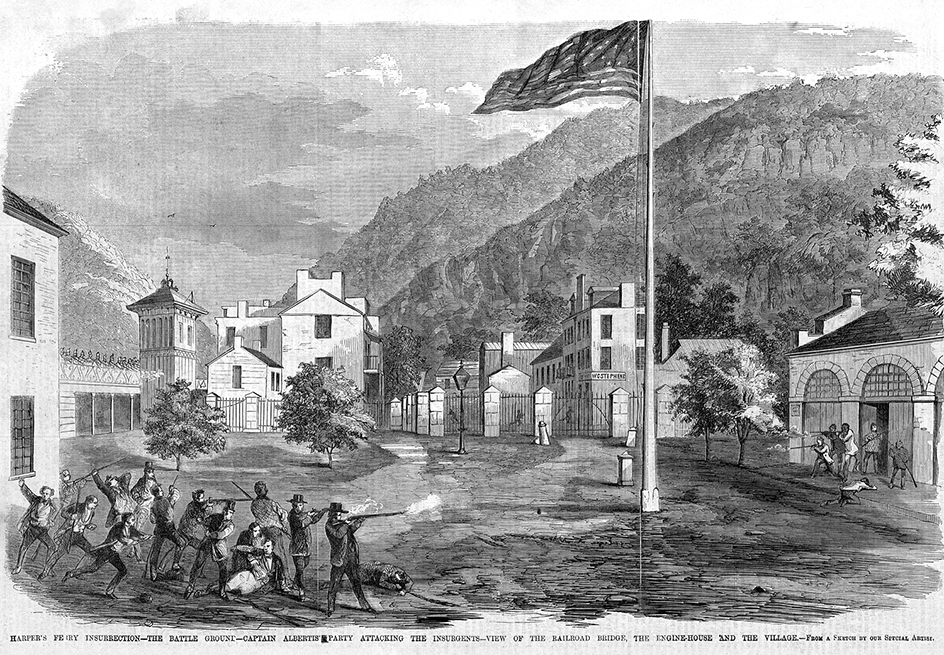

The raid at Harpers Ferry.

In 1859, an extreme abolitionist named John Brown and his followers attempted to start a rebellion among enslaved people by seizing the federal arsenal in Harpers Ferry, Virginia (now West Virginia). Brown was captured 28 hours later by troops under Colonel Robert E. Lee. Within a few weeks, he was convicted of treason and hanged. Many Southerners saw the raid as evidence of a Northern plot to end slavery by force.

Developments in the political party system

Anger over the Kansas-Nebraska Act led to the founding of the Republican Party in the North in 1854. Members of the Republican Party considered slavery evil and opposed its extension into Western territories. Many Whigs and Democrats—members of the nation’s two largest parties—joined the new party. They included Abraham Lincoln, a former Whig. Some other Americans belonged to the Know-Nothing Party, which blamed immigrants and Roman Catholics for the country’s problems. The Republican Party’s first presidential candidate, John C. Frémont, won most of the Northern vote and almost the presidency in 1856. But Democrat James Buchanan was elected president.

In 1858, the Democratic Party was divided over a constitution that proslavery Kansans hoped to have adopted when the Kansas territory became a state. Buchanan and another party leader, Senator Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois, took opposite positions on the constitution. Buchanan favored it, and Douglas opposed it. The conflict between proslavery and antislavery Democrats caused the party to split into Northern and Southern branches in 1860.

The Republicans chose Abraham Lincoln as their candidate in the 1860 presidential election. Douglas ran on the Northern Democratic ticket. Vice President John C. Breckinridge was the Southern Democratic candidate. Some former members of the Whig and Know-Nothing parties—which had disbanded by 1860—formed the Constitutional Union Party and nominated former Senator John Bell of Tennessee.

Lincoln won all the electoral votes of every free state except New Jersey, which awarded him four of its seven votes. He thus gained a majority of electoral votes and won the election. However, Lincoln received less than 40 percent of the popular vote, almost none of which came from the South. Southerners feared Lincoln would restrict or end slavery.

Secession

Before the 1860 presidential election, Southern leaders had urged that the South secede (withdraw) from the Union if Lincoln should win. Many Southerners favored secession as part of the idea that the states have rights and powers that the federal government cannot legally deny. The supporters of states’ rights held that the national government was a league of independent states, any of which had the right to secede.

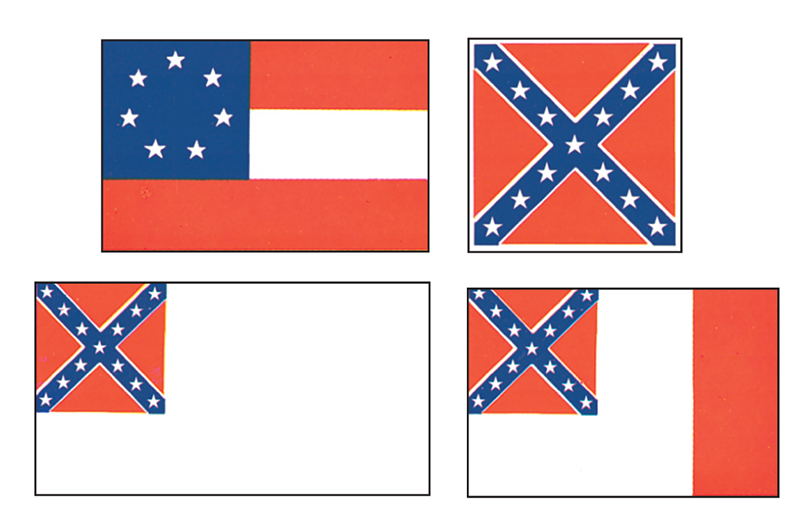

In December 1860, South Carolina became the first state to secede. Five other states—Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, and Louisiana—followed in January 1861. On Feb. 4, 1861, representatives from the six states met in Montgomery, Alabama, and established the Confederate States of America. They elected Jefferson Davis of Mississippi as president and Alexander H. Stephens of Georgia as vice president of the Confederate States. On March 2, Texas joined the Confederacy. Lincoln was inaugurated two days later.

In his inaugural address, Lincoln avoided any threat of immediate force against the South. But he stated that the Union would last forever and that he would use the nation’s full power to hold federal possessions in the South. One of the possessions, the military post of Fort Sumter, lay in the harbor of Charleston, South Carolina. The Confederates fired on the fort on April 12 and forced its surrender the next day. On April 15, Lincoln called for Union troops to regain the fort. The South regarded the move as a declaration of war. Virginia, Arkansas, North Carolina, and Tennessee soon joined the Confederacy.

Virginia had long been undecided about which side to join. Its decision to join the Confederacy boosted Southern morale. Richmond, Virginia’s capital, became the capital of the Confederacy in May.

Mobilizing for war

When the American Civil War began, about 22 million people lived in the North. About 9 million people, including 4 million enslaved people, lived in the South. The North had around 4 million men from 15 through 40 years old—the approximate age range for combat duty. The South had only about 1 million white men in that range. The North began to use Black soldiers in 1863. The South did not attempt to recruit Black men as soldiers until the war’s closing days.

How the states lined up

Eleven states fought for the Confederacy. They were Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and Virginia. Twenty-three states fought for the Union. These states were California, Connecticut, Delaware, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Ohio, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Vermont, and Wisconsin. The territories of Colorado, Dakota, Nebraska, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah, and Washington also fought for the Union.

A number of slave states lay between the North and the Deep South. Some people in those border states supported the North, but others believed in the Southern cause. When the war began, both the Union and the Confederacy made strong efforts to gain the support of those states. Border states that joined the Southern side were Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Arkansas. However, Virginians in the western part of the state remained loyal to the Union and formed the new state of West Virginia in 1863. Border states that stayed in the Union were Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky, and Missouri. But secessionist groups in Kentucky and Missouri set up separate state governments and sent representatives to the Confederate Congress. Some of the heaviest fighting of the war occurred in the border states.

In both the North and the South, some families were torn by divided loyalties to the Union and the Confederacy. One of Kentucky Senator John J. Crittenden’s sons, Thomas, became a Union general. Another son, George, became a Confederate general. George H. Thomas, one of the Union’s best generals, was born in Virginia. Admiral David Farragut, who defeated Southern naval forces at New Orleans and Mobile Bay, was born in Tennessee. Three half brothers of Mary Todd Lincoln, Abraham Lincoln’s wife, died fighting for the Confederacy. The husband of one of her half sisters was a Confederate general who was also killed.

Building the armed forces

At the beginning of the Civil War, neither the North nor the South had a plan to call up troops. The Regular Army of the United States at that time consisted of only about 16,000 men, most of whom fought for the North. Both sides tried to raise their armies by appealing to volunteers. That system worked at first. Individual states, rather than the Union or Confederate governments, recruited most volunteers and often equipped them. Any man who wanted to organize a company or a regiment could do so. In the North, especially late in the war, volunteers often received a bounty (payment for enlisting). The bounty system encouraged thousands of bounty jumpers, who deserted after being paid. Many bounty jumpers enlisted several times, often using a different name each time.

The draft.

As the war went on, enthusiasm for it faded and volunteer enlistments decreased. Both sides then tried drafting soldiers. The first Southern draft law was passed in April 1862 and made all able-bodied white men from ages 18 through 35 liable for three years’ service. By February 1864, the limits had been changed to 17 and 50. The Northern program, begun in March 1863, drafted men from ages 20 through 45 for three years. Exceptions to the draft were made in the North and South, however, and both sides allowed a draftee to pay a substitute to serve for him. In addition, a draftee in the North could pay the government $300 to avoid military service. The system seemed unfair, and many soldiers grumbled that they were involved in “a rich man’s war and a poor man’s fight.” But on the whole, both armies had a fair representation of soldiers from the various social groups of their regions.

The draft worked poorly and was extremely unpopular in many areas of both the North and the South. In some isolated hill country of the South, it could not be enforced. In July 1863, armed antidraft protesters in New York City set fire to buildings and took over parts of the city before police and the Army restored order. However, the Northern and Southern draft succeeded in its main purpose, which was to stimulate volunteering.

No one knows exactly how many men served in the American Civil War. The totals on both sides included many short-term enlistments and repeaters (men who served more than once). According to the best estimates, 2,100,000 men served in the Union Army, and 800,000 men served in the Confederate Army. A little more than half the men of military age served for the North. A larger proportion of eligible men—almost four-fifths—served for the South. In the South, enslaved Black people performed most of the labor, thereby freeing a greater percentage of eligible whites for military duty. Immigrants made up about 24 percent of the Union Army and about 10 percent of the Confederate Army.

The Confederate Army reached peak strength in 1863, then declined. But the Union Army grew. In the last year of the war, the North had over a million soldiers. The South probably had no more than 200,000. About 10 percent of the soldiers on both sides deserted. Desertion from the Confederate Army became most common in the last months of the war, when Southern morale began to collapse and defeat seemed certain.

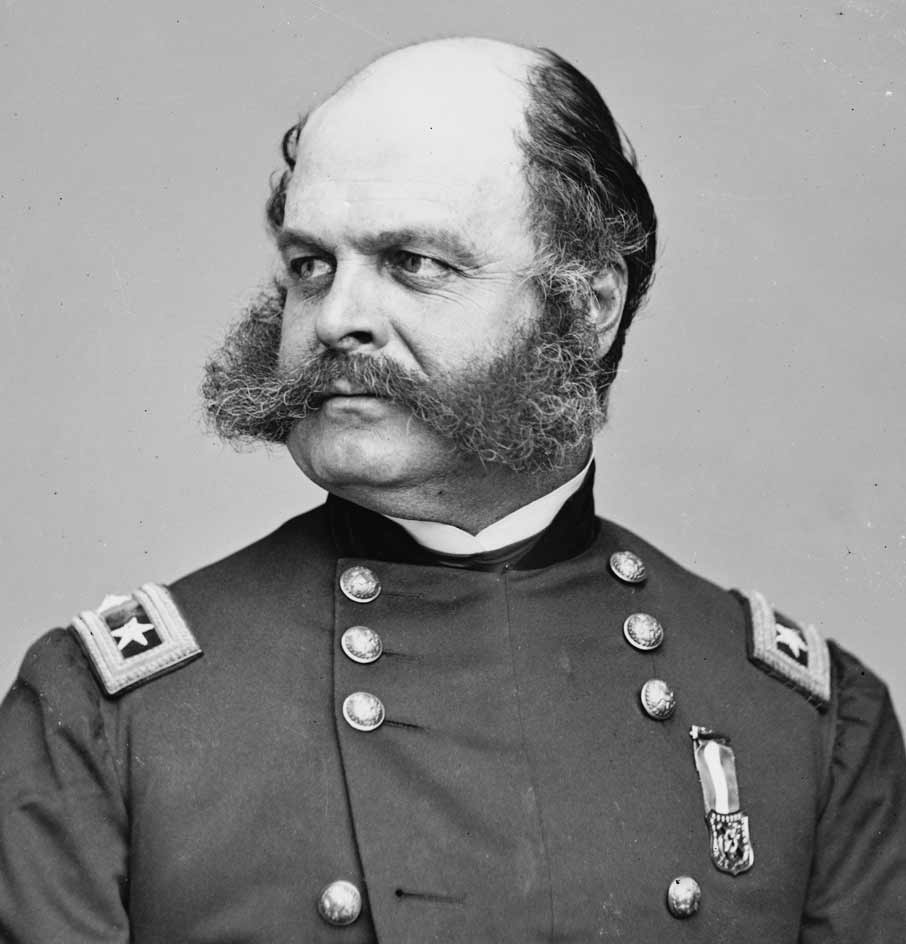

The commanding officers.

As commander in chief of the U.S. armed forces, Abraham Lincoln had to choose the Union’s top military officers. Jefferson Davis had the same task in the Confederacy. Davis fortunately had General Robert E. Lee to take command of the Eastern Confederate Army. Lee’s able officers included Generals Stonewall Jackson and James Longstreet. Confederate commanders in the West—Generals Albert Sidney Johnston, Pierre G. T. Beauregard, Braxton Bragg, and Joseph E. Johnston—were less successful.

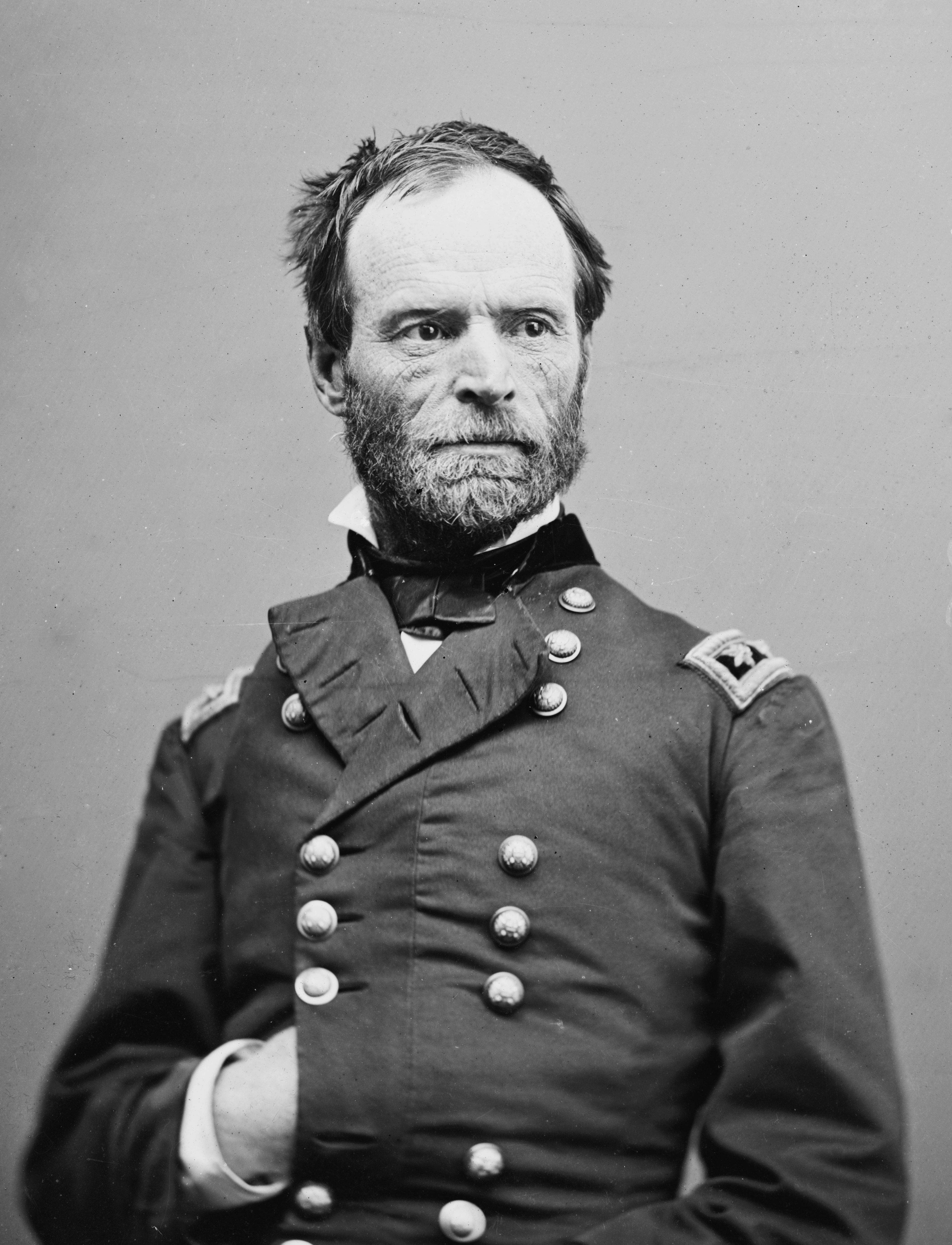

Lincoln tried several commanders for the Eastern Union Army, which came to be called the Army of the Potomac. They were, in turn, Generals Irvin McDowell, George B. McClellan, John Pope, McClellan again, Ambrose E. Burnside, Joseph Hooker, and George G. Meade. All had serious weaknesses. Lincoln’s Western generals—Henry W. Halleck, Don Carlos Buell, and William S. Rosecrans—also failed to meet his expectations. But as the war progressed, four outstanding generals emerged to lead the Union armies to victory. They were Ulysses S. Grant, William T. Sherman, Philip H. Sheridan, and George H. Thomas.

The enlisted men.

Civil War soldiers were much like American enlisted men of earlier and later wars. They fought well but remained civilians, with a civilian’s dislike of military rules. In most regiments, the men all came from the same area. Many units elected their own officers.

Civil War soldiers received more leaves and furloughs than did soldiers of previous wars, and they had better food and clothing. But compared with today’s standards, they had a hard life. Both sides paid their soldiers poorly. Food supplies consisted mainly of flour, corn meal, beef, beans, and dried fruit. Many soldiers made their own meals. Armies on the march ate salt pork and hard biscuits called hardtack. Poorly made clothing of shoddy (rewoven wool) often fell apart in the first storm. Southern soldiers at times lacked shoes and had to march and fight barefoot.

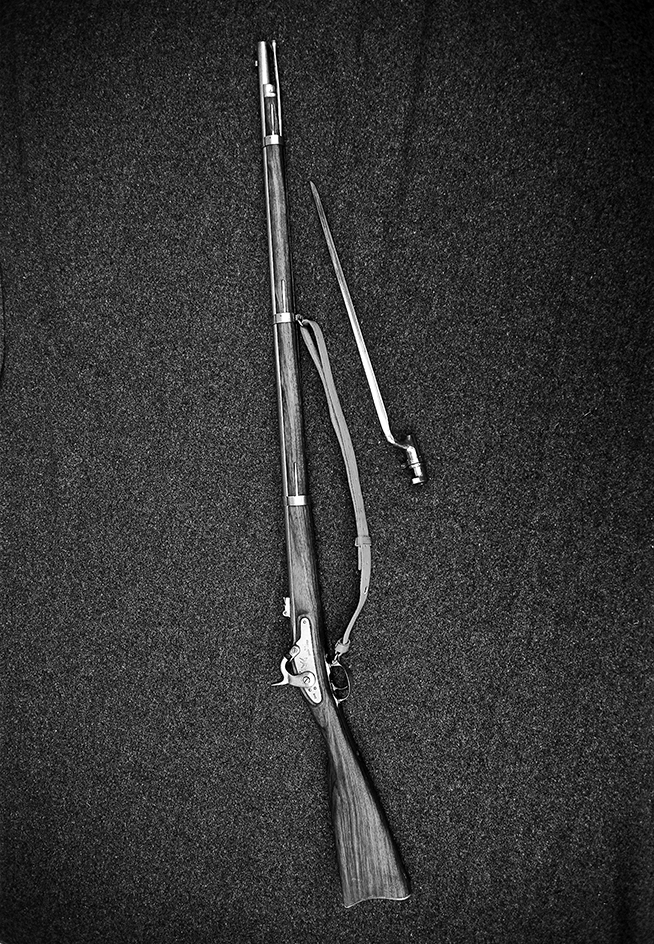

Most Civil War soldiers carried muzzleloading rifles. Because the guns could fire only one shot at a time, they seem primitive today. But technological advances, especially the use of rifling (spiral grooves) in the barrels, had increased the accuracy of these weapons to nearly 400 yards (366 meters). The technological advances made little difference to most soldiers, however, because the soldiers lacked training or experience.

The high death rate.

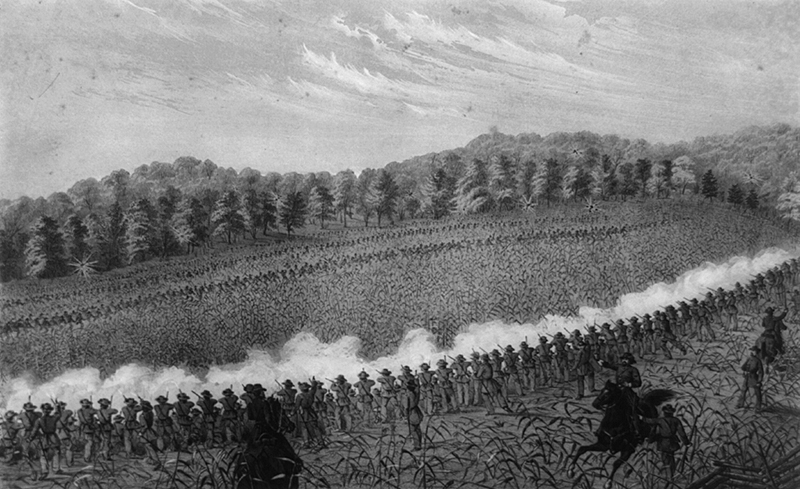

Civil War combat was frequently disorganized and ineffective. The armies were made up mostly of inexperienced soldiers commanded by enthusiastic but unprepared officers. Offensive maneuvers often bogged down as waves of attackers failed to press on to success. Even in major victories, the winners often failed to capture the opposing force. Professional European soldiers scorned the performance of the Civil War armies as little better than “one armed mob chasing another armed mob across the countryside.”

Many battles took a terrible toll in human lives. An army often had 25 percent of its men killed, wounded, captured, or otherwise lost in a major battle. Among some regiments at the Battle of Gettysburg and other battles, the death rate alone ran as high as 25 percent or more. The heavy death toll led Civil War soldiers to devise the first dog tags for identification in case they were killed. A soldier would print his name and address on a handkerchief or a piece of paper and pin it to his uniform before going into battle.

Black Americans and the war

Early Black participation.

Early in the war, Black Americans in the North who wanted to fight to end slavery tried to enlist in the Union Army. But the Army rejected them. Most white people felt the war was a “white man’s war.”

As Northern armies drove into Confederate territory, enslaved people flocked to Union camps. After a period of uncertainty, the Union government decided to allow them to perform support services for the Northern war effort. In time, as many as 200,000 Black Americans worked for Union armies as cooks, laborers, nurses, scouts, and spies.

The Emancipation Proclamation.

Black leaders, such as the formerly enslaved reformer Frederick Douglass of New York, saw the war as a road to emancipation (freedom) for enslaved people. However, the idea of emancipation presented problems in the North. Most Northerners—even though they may have opposed slavery—were convinced of Black inferiority. Many of them feared that emancipation would cause a mass movement of Black Southerners to the North. Northerners also worried about losing the border states loyal to the Union because those states were strongly committed to slavery. Skillful leadership was needed as the country moved toward Black freedom. Lincoln supplied that leadership by combining a clear sense of purpose with a sensitivity to the concerns of various groups.

On Sept. 22, 1862, Lincoln issued a preliminary order to free enslaved people. It declared that all enslaved people in states in rebellion against the Union on Jan. 1, 1863, would be forever free. It did not include the slave states loyal to the Union—Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky, and Missouri. Lincoln had no legal authority to deal with slavery in states where the state government was not fighting against the federal government.

On Jan. 1, 1863, Lincoln issued the final order as the Emancipation Proclamation. The Emancipation Proclamation, though legally binding, was a war measure that could be reversed later. Therefore, in 1865, Lincoln helped push through Congress the 13th Amendment to the Constitution, which abolished slavery throughout the nation. For his effort in freeing enslaved people, Lincoln is known as the “Great Emancipator.”

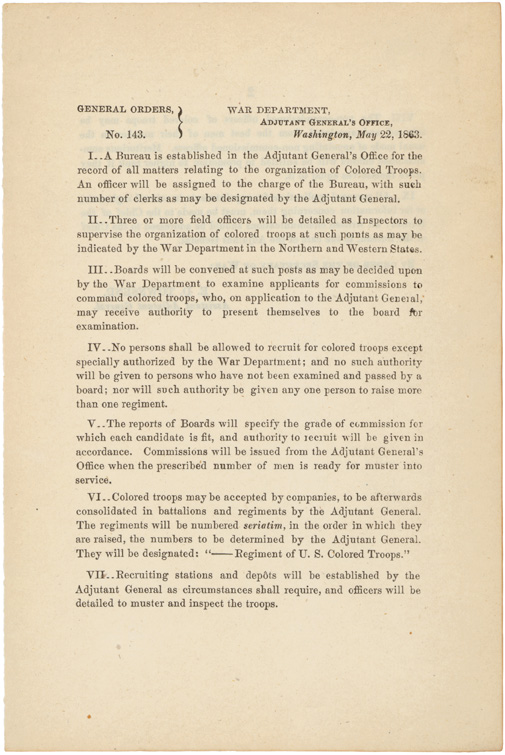

The use of Black troops.

The Emancipation Proclamation also announced Lincoln’s decision to use Black troops, though many white people believed that Black men would make poor soldiers. About 180,000 Black soldiers served in the Union Army. Two-thirds of them were Southerners who had fled to freedom in the North. About 20,000 Black sailors served in the Union Navy, which had been open to Black men long before the war. Black troops formed 166 all-Black regiments, most of which had white commanders. Only about 100 Black soldiers were made officers.

Black soldiers fought in nearly 500 Civil War engagements, including 39 major battles. About 35,000 Black servicemen lost their lives. Altogether, 23 Black soldiers were awarded the Medal of Honor, the nation’s highest military award, for heroism. A Black regiment was one of the first Northern units to march into Richmond after it fell. Lincoln then toured the city, escorted by Black cavalry.

At first, Black soldiers received only about half the pay of white soldiers and no bounties for volunteering. In 1864, Congress granted Black soldiers equal pay and bounties. However, other types of official discrimination continued. For example, most Black soldiers were allowed to perform only noncombat duties. But some Black soldiers who had the opportunity to go into combat distinguished themselves. The bravery of Black soldiers in the 1863 Mississippi Valley campaign surprised most Northerners. But protests against the use of Black troops continued.

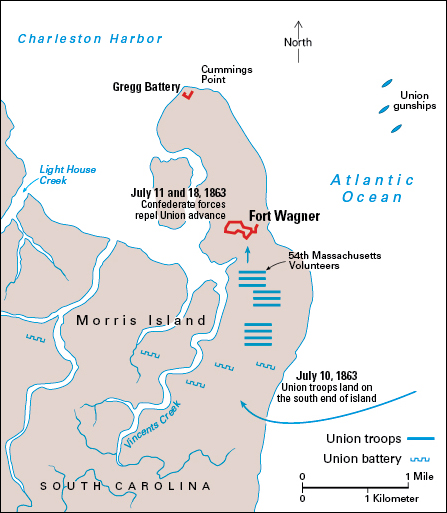

Later in 1863, the 54th Massachusetts Volunteers—the first Black troops from a free state to be organized for combat in the Union Army—stormed Fort Wagner in Charleston Harbor. Their bravery turned the tide of Northern public opinion to accept Black troops. Lincoln wrote that when peace came “there will be some Black men who can remember that, with silent tongue, and clenched teeth, and steady eye, and well-poised bayonet, they have helped mankind on to this great consummation; while, I fear, there will be some white ones, unable to forget that, with malignant heart, and deceitful speech, they have strove to hinder it.”

Reaction in the South.

The Confederacy objected strongly to the North’s use of Black soldiers. The Confederate government threatened to kill or enslave any captured officers or enlisted men of Black regiments. Lincoln replied by promising to treat Confederate prisoners of war the same way. Neither side carried out its threats, but the exchange of prisoners broke down mainly over the issue of Black prisoners.

The North’s success in using Black soldiers slowly led Southerners to consider doing the same. In the spring of 1865, following a strong demand by General Lee, the Confederate Congress narrowly approved the use of Black soldiers. However, the war ended soon thereafter.

The home front

The American Civil War became the first war to be completely and immediately reported in the press to the people back home. Civilians in the North were especially well informed of the war’s progress. Northern newspapers sent their best correspondents into the field and received their reports by telegraph. Winslow Homer and many other artists and illustrators produced war scenes for such magazines as Harper’s Weekly. Mathew Brady, Alexander Gardner, and other pioneer photographers captured the horrors of the battlefield and the humanity of the soldiers in thousands of news pictures.

The war inspired a flood of patriotic songs. Northern civilians and soldiers sang such songs as “The Battle Cry of Freedom,” “Marching Through Georgia,” and “John Brown’s Body.” Early in the war, Julia Ward Howe wrote “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” to the tune of “John Brown’s Body.” Southern soldiers marched to war to the stirring music of “Dixie” and “The Bonnie Blue Flag.” Some Northern songs, such as “Tenting on the Old Camp Ground” and “When Johnny Comes Marching Home,” also became popular in the South. And some Southern songs—for example, the mournful “Lorena” and “All Quiet Along the Potomac Tonight”—were also popular in the North.

In the North

Government and politics.

After the attack on Fort Sumter, Lincoln boldly ordered troops to put down the rebellion, increased the size of the U.S. Army, proclaimed a naval blockade of the South, and spent funds without congressional approval. He became the first president to assume vast powers not specifically granted by the Constitution. He suspended habeas corpus in many cases in which people opposed the war effort. Habeas corpus is a right that guarantees a person under arrest a chance to be heard in court. Its suspension received bitter criticism. Yet many traditional American freedoms continued to flourish, even though the nation was in the midst of a civil war.

Opposition to the war and Lincoln’s policies came chiefly from the Democratic Party, especially from a group known as the Peace Democrats, who wanted the war stopped. Republicans considered the Peace Democrats disloyal and treacherous and called them Copperheads, after the poisonous snake. Other protesters of the war joined secret antigovernment societies, such as the Knights of the Golden Circle. The Lincoln administration was also criticized by so-called Radical Republicans. They wanted the government to move more rapidly to abolish slavery and to make sweeping changes in the Southern way of life. Such disputes continued throughout the war.

Economy.

The Civil War brought booming prosperity to the North. Government purchases for military needs stimulated manufacturing and agriculture. The production of coal, iron and steel, weapons, shoes, and woolen clothing increased greatly. Farmers vastly expanded their production of wheat, wool, and other products. Exports to Europe of beef, corn, pork, and wheat doubled. Factories and farms made the first widespread use of labor-saving machines, such as the sewing machine and the reaper.

Although the Civil War brought prosperity to the North, financing the war was difficult. Taxes and money borrowed through the sale of war bonds became major sources of income. The government also printed more paper money to meet its financial needs. But by increasing the money supply, the government promoted inflation. Wages did not keep up with inflation through much of the war, and factory workers struck for higher pay. But as the war went on, war production—and finally victory—helped the North grow ever stronger.

During the Lincoln administration, Congress passed the most important series of economic acts in American history to that time. It established the national banking system, a uniform (standard) currency, and the Department of Agriculture. The Pacific Railroad Act of 1862 provided for the building of the nation’s first transcontinental rail line. The Homestead Act of 1862 granted settlers public land in the West free or at low cost. The Land-Grant, or Morrill, Act of 1862 helped states establish agricultural and technical colleges. Under Lincoln, Congress also passed the first federal income tax. Altogether, the economic progress in the North brought about by and during the Civil War helped put the United States on the road to becoming the world’s greatest industrial power by the late 1800’s.

In the South

Government and politics.

During the Civil War, the South tried to bring political power under the control of a single authority. But it was not successful. Southerners had long opposed a strong central government. During the war, some of them found it difficult to cooperate with officials of both the Confederacy and their own states and cities. States’ rights supporters backed the war but opposed the draft and other actions needed to carry it out. And Jefferson Davis lacked Lincoln’s leadership abilities. For example, Lincoln believed he had the power to suspend the law if necessary, and he did so. Davis asked the Confederate Congress for such power but received only limited permission.

Economy.

As in the North, manufacturing and agriculture in the South were adapted to the needs of war. Factories converted from civilian to wartime production. For example, the Tredegar Iron Works in Richmond became the South’s main source of cannons. Cotton cultivation dropped sharply, while food production was greatly increased.

The South thus tried to adjust to meet wartime needs, but its economy became strained almost to the breaking point. The attempt to finance the war by taxation and borrowing from the people failed. The Confederacy’s solution to the problem was to print large amounts of paper money, which led to an extremely high inflation rate. By the end of the war, prices were 10 times higher than they were at the start. In 1865, flour cost up to $300 a barrel, and shoes $200 a pair. In time, Southerners had to make clothes of carpets and curtains and print newspapers on the back of wallpaper.

Confederate troops were never as well equipped as their Northern foes. As resources were used up and the tightening naval blockade severely reduced imports, matters got worse. The Confederate government then passed the Impressment Act of 1863. The act permitted government agents to seize from civilians food, horses, and any other supplies the Army needed. The civilians received whatever the agents decided to pay.

Relations with Europe.

At the beginning of the war, Southern leaders hoped that European countries—especially France and the United Kingdom—would come to the aid of the Confederacy. Southerners believed that France and the United Kingdom would be forced to support the Confederacy because their textile industries depended on Southern cotton. The efforts of Southern statesmen to persuade the European powers to help the Confederacy came to be called “cotton diplomacy.”

As a result of cotton diplomacy, France and the United Kingdom allowed the Confederacy to have several armed warships built in their shipyards. But the South never won European recognition of the Confederacy as an independent nation or obtained major aid. Northern grain had become important in Europe, which had suffered several crop failures. At the same time, Southern cotton was increasingly replaced by cotton from India and Egypt. The Emancipation Proclamation made the Civil War a fight against slavery. The proclamation deeply impressed those Europeans who opposed slavery. Such skillful Northern diplomats as Charles Francis Adams also helped persuade the European powers not to recognize the Confederacy. But most important, Britain and France would not fight on the side of the South unless the Confederacy could show that it might win final victory. And that never happened.

The war in the East—1861-1863

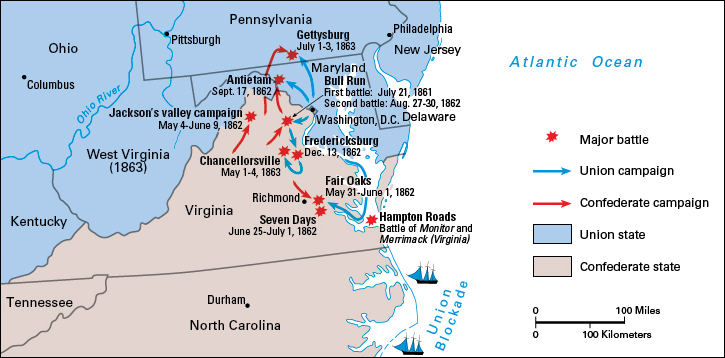

The Appalachian Mountains divided the war into two main theaters of operations (military areas). The Eastern theater stretched east of the mountains to the Atlantic Ocean. The Western theater lay between the mountains and the Mississippi River. A third theater, west of the Mississippi, saw only minor action.

Many Civil War battles have two names because the Confederates named them after the nearest settlement, and Northerners named them after the nearest body of water. In such battles described in this article, the Northern name is given first, followed by the Confederate name in parentheses.

Opening battles

Fort Sumter.

The American Civil War began on April 12, 1861, when Confederate forces under General Pierre G. T. Beauregard attacked Fort Sumter, a U.S. Army post in the harbor of Charleston, South Carolina. The Union troops surrendered on April 13 and evacuated the fort the next day.

Following the fall of Fort Sumter, a Union army of about 18,000 men under General Robert Patterson held the northern end of the fertile Shenandoah River Valley, which lay in Virginia west of the rival capitals of Washington, D.C., and Richmond. Another Union force of about 31,000 under General Irvin McDowell moved into eastern Virginia to attack Southern forces. A Confederate army under Beauregard faced McDowell at Manassas, Virginia, about 25 miles (40 kilometers) southwest of Washington. General Joseph E. Johnston commanded Confederate troops in the Shenandoah Valley. Those forces, along with other scattered troops, added up to about 35,000 Confederates ready for action.

First Battle of Bull Run

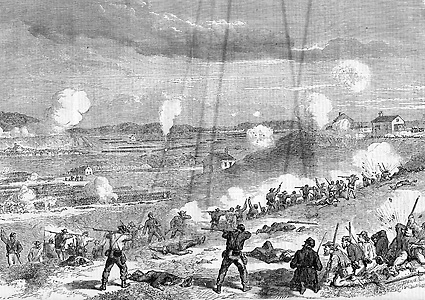

(or First Battle of Manassas). In July 1861, McDowell approached Manassas, which lay on a creek called Bull Run. McDowell thought his troops could destroy Beauregard’s forces while the Union troops in the Shenandoah Valley kept Johnston occupied. But Johnston slipped away and traveled by rail to join Beauregard just before the battle.

The opposing forces, both composed mainly of poorly trained volunteers, clashed on July 21. The North launched several assaults. During one attack, Confederate General Thomas J. Jackson stood his ground so firmly that he received the nickname “Stonewall.” After halting several assaults, Beauregard counterattacked. The tired Union forces fled to Washington, D.C., in wild retreat. After the battle, some Southerners regretted not having moved on to capture Washington. But such an attempt would probably have failed.

The North realized that it faced a long fight. The war would not be over in three months, as many Northerners had predicted. Confederate confidence in final victory soared and remained high for the next two years.

The drive to take Richmond

After Bull Run, Lincoln made General George B. McClellan commander of the Army of the Potomac in the East. During the winter of 1861-1862, McClellan assembled a force with which he planned to capture Richmond from the southeast. He wanted to land his men on the peninsula between the York and James rivers and advance along one of the rivers toward the Southern capital. But before McClellan could move, a naval action changed his plans.

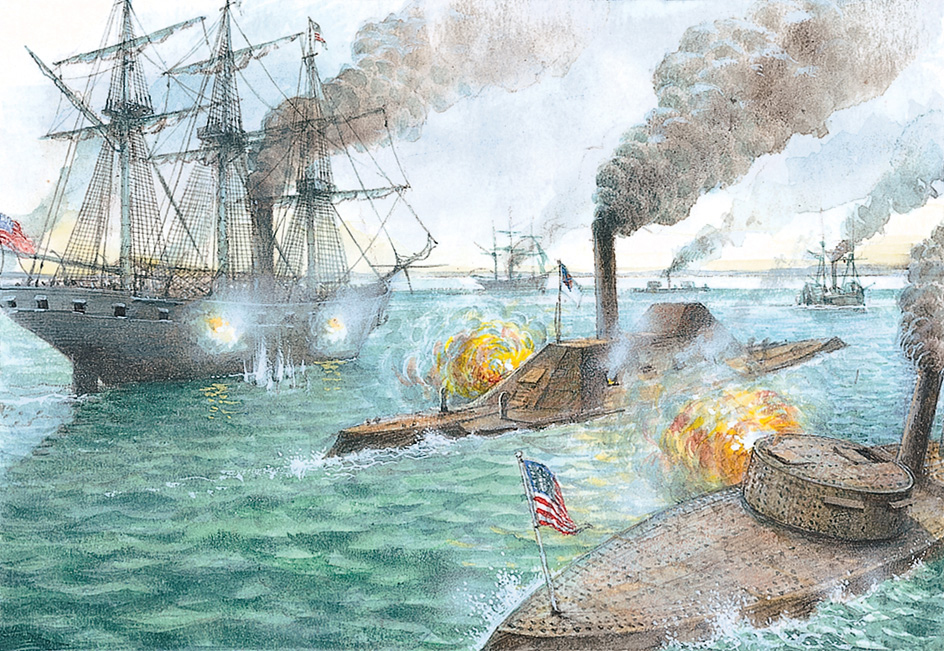

First battle between ironclads.

In 1861, the Confederates had raised a sunken federal ship, the Merrimack, off Norfolk, Virginia, and covered the wooden vessel with iron plates. The South used the ironclad ship, renamed the Virginia, to stage the South’s greatest naval challenge to the North. On March 8, 1862, the Virginia attacked Northern ships at Hampton Roads, a channel that empties into Chesapeake Bay. It destroyed two Northern vessels and grounded three others. When the ship returned the next day to finish the job, it faced the Monitor, an ironclad ship designed especially for the Northern Navy. History’s first battle between ironclad warships followed. Although neither ship won, the Monitor proved to be the superior vessel. Later, the U.S. Navy built a large ironclad fleet modeled after it.

The peninsular campaign.

After the battle of the ironclads, McClellan landed on the peninsula between the York and James rivers with more than 100,000 men. He occupied Yorktown and advanced along the York River. He could not follow the James River because the Virginia was on the river. By late May 1862, McClellan was within 6 miles (10 kilometers) of Richmond. Johnston led an attack against McClellan on May 31. But the Confederates failed to follow up their success and were driven back toward Richmond. In the two-day fight, called the Battle of Fair Oaks (or Battle of Seven Pines), Johnston was wounded. General Robert E. Lee was given command of Johnston’s army, which Lee called the Army of Northern Virginia.

Jackson’s valley campaign.

The Confederacy feared that McClellan would receive reinforcements from the numerous troops that had stayed behind to protect Washington, D.C. Stonewall Jackson therefore launched a campaign in the Shenandoah Valley. He planned to make the Northerners think he was going to attack Washington. In a series of brilliant moves from May 4 through June 9, 1862, Jackson advanced about 350 miles (560 kilometers) up the Shenandoah Valley and beyond, toward the Potomac River. His 17,000 men received the name “foot cavalry” because they marched so fast. Jackson won four battles against the Union armies. He reached the Potomac but soon had to retreat. However, he had forced the Union to withhold the powerful reinforcements that McClellan had counted on.

Stuart’s raid.

While Lee planned his strategy as the new commander of the Army of Northern Virginia, Confederate General Jeb Stuart led a remarkable cavalry raid. In June 1862, Stuart and about 1,200 men galloped completely around McClellan’s army of 100,000 in three days, losing only one man. Stuart’s raid gained information about Union troop movements and boosted Southern morale.

Battles of the Seven Days.

Lee planned a daring move to destroy McClellan’s army, which lay straddled over the Chickahominy River. With his forces reinforced by Jackson’s men to about 85,000, Lee’s forces faced McClellan’s in a series of attacks, called the Battles of the Seven Days, from June 25 through July 1, 1862. The advantage shifted from side to side during the battles, but McClellan believed that his forces were hopelessly outnumbered. He finally retreated to the James River, and Richmond was saved from capture. McClellan’s army was ordered to northern Virginia to be united with a force under General John Pope. McClellan was to command the combined army.

The South strikes back

Second Battle of Bull Run

(or Second Battle of Manassas). Lee moved rapidly northward to attack Pope, stationed at Manassas, before McClellan’s men could join him. Lee sent Jackson ahead to move behind Pope’s army and force a battle. On Aug. 29, 1862, Pope attacked Jackson, sending in McClellan’s troops as fast as they arrived. Meanwhile, Lee and General James Longstreet had joined Jackson. Pope attacked Lee’s army on August 30, but a Confederate counterattack swept the Union forces from the field. The beaten Northern troops plodded back to Washington.

Battle of Antietam

(or Battle of Sharpsburg). The South hoped to gain European recognition by winning a victory in Union territory. Lee invaded Maryland in September 1862. He divided his army, sending about half with Jackson to capture Harpers Ferry, Virginia, which Union troops occupied. McClellan moved to meet Lee with about 90,000 men. On September 13, a Union soldier found a copy of Lee’s orders to his commanders wrapped around three cigars at an abandoned Confederate campsite. Lee learned of the loss and took up a position at Sharpsburg, a town on Antietam Creek in Maryland. But McClellan did not immediately attack, giving the Confederate forces time to reunite after Jackson’s success at Harpers Ferry. On September 17, McClellan launched a series of attacks that almost cracked the Southern lines. But then, the last of Lee’s absent troops, headed by General A. P. Hill, arrived and saved the day. Lee’s force of about 40,000 men suffered heavy losses and had to retreat to Virginia.

Antietam was the bloodiest single day of the Civil War. About 2,000 Northerners and 2,700 Southerners were killed. About 19,000 men from both sides were wounded, of which about 3,000 later died. Because Lee retreated, the North called Antietam a Union victory. On September 22, Lincoln issued the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. He had been waiting for a Northern victory as a good time for the proclamation.

Battle of Fredericksburg.

As bloody as Antietam was, McClellan had more fresh troops under him after the battle than Lee had left in his entire army. Yet McClellan permitted the Army of Northern Virginia to retreat with almost no interference. Lincoln, who had long felt that McClellan was not aggressive enough, replaced him with General Ambrose E. Burnside as commander of the Army of the Potomac.

Burnside decided to attack Lee at Fredericksburg, Virginia. The Confederates, about 73,000 strong, established a line of defense along fortified hills called Marye’s Heights. On Dec. 13, 1862, Burnside’s men tried to storm the hills in a brave but hopeless attack. The Union suffered nearly 13,000 casualties—soldiers killed, wounded, missing, or captured—and retreated. Burnside was relieved of command at his own request.

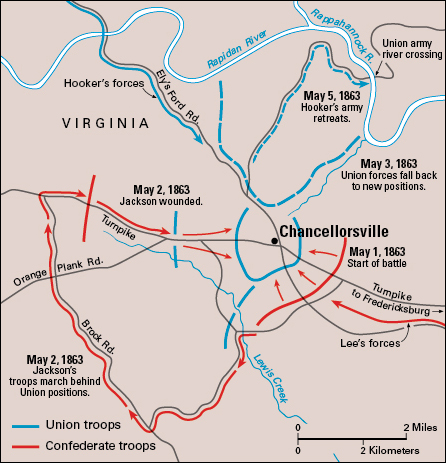

Battle of Chancellorsville.

General Joseph Hooker replaced Burnside. In the spring of 1863, the Army of the Potomac numbered about 138,000 men. Lee’s forces totaled about 60,000 and still held the line of defense at Fredericksburg. Hooker planned to keep Lee’s attention on Fredericksburg while he sent another force around the town to attack the Confederate flank (side).

The flanking movement began on April 27, 1863, and seemed about to succeed. But then, Hooker hesitated. On May 1, he withdrew his flanking troops to a defensive position at Chancellorsville, a settlement just west of Fredericksburg. The next day, Lee left a small force at Fredericksburg and boldly moved to attack Hooker. He sent Stonewall Jackson to attack Hooker’s right flank, while he struck in front. The attack, on May 2, cut the Northern army almost in two, but Union troops managed to set up a defensive line. Hooker retreated three days later. During the battle, Jackson was shot accidentally by his own men. His left arm had to be amputated. Lee told Jackson’s chaplain: “He has lost his left arm; but I have lost my right arm.” Jackson died on May 10.

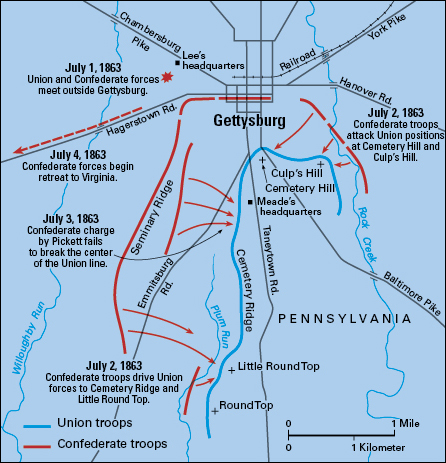

Battle of Gettysburg.

In June 1863, Lee’s army swung up the Shenandoah Valley into Pennsylvania. The Army of the Potomac followed it northward. Both armies moved toward the little town of Gettysburg. When it appeared that the battle was about to begin, Lincoln put General George G. Meade, a Pennsylvanian, in command of the Union troops. The shooting started when a Confederate brigade, searching for badly needed shoes, ran into Union cavalry near Gettysburg on July 1. For the first three days of July, a Northern army of about 90,000 men fought a Southern army of about 75,000 in a battle that became the turning point of the war.

On the first day, the two armies maneuvered for position. By the end of the day, Northern troops had been pushed from west and north of Gettysburg, and they settled into a strong defensive location on high ground south of the town. The front ran about 3 miles (5 kilometers) along Cemetery Ridge. At one end, the Union’s right, were Cemetery Hill and Culp’s Hill. At the other end were two hills called Little Round Top and Round Top. Confederate forces occupied Gettysburg and then Seminary Ridge, to the west.

On the second day, July 2, Lee hoped to crush the Union position on Cemetery Ridge by striking at both sides of the ridge at the same time. But Lee was unable to carry out his plan. The Union Army put up fierce resistance all along Cemetery Ridge and down to Little Round Top. Lee’s forces met equally furious resistance from Union troops on Culp’s Hill and the eastern side of Cemetery Hill.

On July 3, Lee tried one more time to crack the Union hold on Cemetery Ridge. After a fierce artillery duel, he ordered General George E. Pickett to prepare about 12,000 men to charge the Union lines. The men, marching in battle formation, advanced across an open field and up the slopes of Cemetery Ridge in the face of enemy fire. Only a few troops reached the top of the ridge, where they were quickly shot or captured. Barely half the soldiers involved in the assault returned to Lee, who took complete responsibility for the attack’s failure. Pickett’s charge showed the hopelessness of frontal (head-on) assaults over open ground against a strong enemy. Lee’s attempt to pierce the Union rear with Stuart’s cavalry, which had arrived the night before, also failed.

Lee withdrew his battered army to Virginia after the battle. Much to Lincoln’s disgust, Meade made little effort to follow him, even though Meade had about 20,000 fresh reserves and had received further reinforcements. Lee’s army thus escaped. However, casualties among Lee’s men numbered about 28,000. The Union victory at Gettysburg, together with the capture of Vicksburg, Mississippi, the following day, struck a severe blow to the Confederacy.

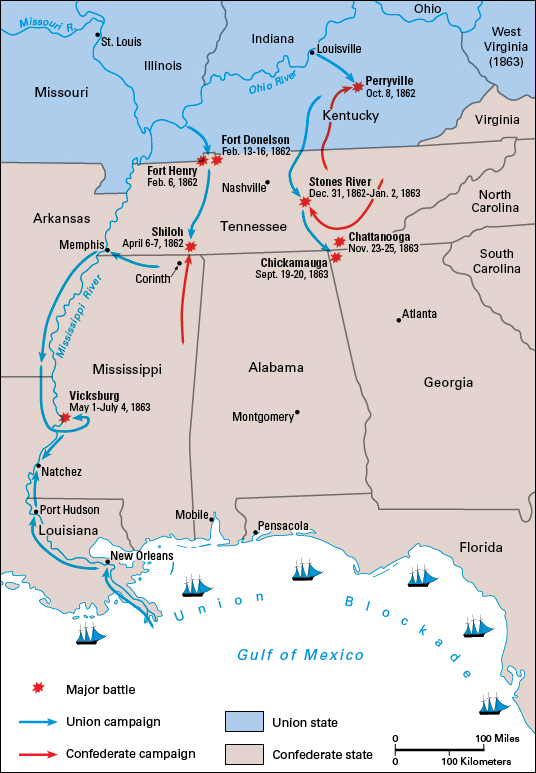

The war in the West—1862-1864

In the Western theater, the North attacked early and hard to seize the Mississippi River. Northern forces in the West totaled about 100,000 men, and Southern forces about 70,000. General Henry W. Halleck led Union forces in Arkansas, Illinois, Iowa, western Kentucky, Minnesota, Missouri, and Wisconsin. General Don Carlos Buell led the Northern forces in Indiana, eastern Kentucky, Michigan, and Ohio. General Albert Sidney Johnston led Southern forces in Arkansas, western Mississippi, and Tennessee. His command included General Earl Van Dorn’s troops in Arkansas.

Fight for the Mississippi Valley

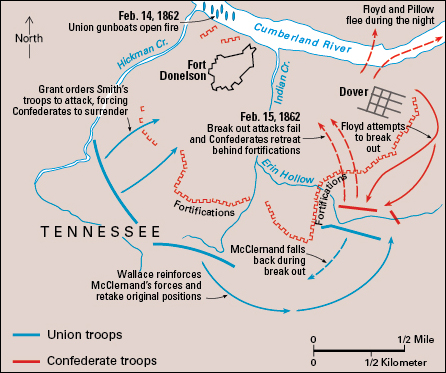

Battles of Fort Henry and Fort Donelson.

The center of the Confederate line in the West rested on two forts about 12 miles (19 kilometers) apart in western Tennessee. They were Fort Henry on the Tennessee River and Fort Donelson on the Cumberland River. If Union forces could capture the forts, the Confederate position in Kentucky and western Tennessee would collapse. Gunboats under orders from General Ulysses S. Grant, commanding officer under Halleck in western Kentucky, took Fort Henry on Feb. 6, 1862. Grant himself moved against Fort Donelson. The Confederate commander, General Simon Bolivar Buckner, asked for “the best terms” of surrender. Grant replied: “No terms except an unconditional and immediate surrender can be accepted.” On February 16, about 13,000 of the Confederate troops stationed at Fort Donelson surrendered. Grant gained the nickname “Unconditional Surrender” Grant and became a Northern hero.

Grant’s army lay between the two flanks of the Confederate forces. To escape destruction, Johnston pulled his troops back to Corinth, Mississippi, a major railroad center. The Confederacy had lost Kentucky and half of Tennessee. West of the Mississippi River, a Union army under General Samuel R. Curtis defeated Van Dorn at Pea Ridge, Arkansas, on March 7 and 8. The defeat put Missouri solidly in Northern hands.

Battle of Shiloh.

Halleck, who had become commander of most Union forces from Ohio to Kansas, ordered Grant to move down the Tennessee River and told Buell to join Grant. Grant and some 40,000 men moved to Pittsburg Landing, Tennessee, a village about 20 miles (32 kilometers) north of Corinth. Johnston and his second in command, General Beauregard, decided to strike Grant before Buell arrived. They planned to destroy Grant’s forces with their army of some 44,000 troops. The Battle of Shiloh, named after a church on the battlefield, occurred on April 6 and 7, 1862. The battle is also called the Battle of Pittsburg Landing.

On the first day, Confederate troops surprised and almost smashed Grant. But Grant held his lines. Johnston was killed in the battle. The next day, Grant received about 25,000 reinforcements, including some 18,000 troops led by Buell. The Confederate army received only about 700 reinforcements. Grant used his now much larger army to force a Southern retreat to Corinth. The Union suffered about 13,000 casualties, and the Confederacy nearly 11,000. Many Northerners urged Lincoln to replace Grant because of the heavy losses. But Lincoln refused, saying, “I can’t spare this man—he fights!”

After Shiloh, Halleck took command of Grant’s and Buell’s forces. He moved southward and forced Beauregard to evacuate Corinth. By early June, the Union held the Mississippi River as far south as Memphis.

Capture of New Orleans.

Meanwhile, Northern forces were moving up the Mississippi River from the South. In April 1862, a naval squadron under Captain David G. Farragut appeared at the mouth of the river. Farragut steamed through the weak Confederate defenses and captured New Orleans on April 25. On May 1, Northerners took control of New Orleans and southern Louisiana, which they held for the rest of the war.

Raids.

Some of the most daring actions of the war occurred behind the front lines. In April 1862, a Union spy named James J. Andrews led 21 men through the Confederate lines to Marietta, Georgia, where they captured a railroad engine named the General. They ran it northward toward Chattanooga, Tennessee, destroying telegraph communications as they went. But Confederate troops in another engine, the Texas, pursued the General and caught it after what came to be called the Great Locomotive Chase. The Confederacy hanged Andrews and 7 of his men.

From mid-April through early May 1863, Colonel Benjamin Grierson took a Union cavalry force of about 1,700 men on raids between Vicksburg, Mississippi, and Baton Rouge, Louisiana. They tore up about 50 miles (80 kilometers) of railroad track and lured Confederate cavalry and infantry regiments away from Union troops massing near Vicksburg.

Confederate Generals Nathan Bedford Forrest and John Hunt Morgan led many cavalry raids into enemy territory. In 1864, for example, Forrest’s men galloped as far north as Paducah, Kentucky, destroying Union supplies and communications lines. Morgan led his men, called Morgan’s Raiders, on a dash through Kentucky, Indiana, and Ohio in July 1863. They destroyed property worth about $576,000 before being captured. Morgan escaped in November but was killed a year later in Tennessee.

Battle of Perryville.

After Corinth fell to Union forces, Halleck went to Washington, D.C., to act as Lincoln’s military adviser. He assigned Grant to guard communications along the Mississippi and ordered Buell, who had yet to prove himself, to capture Chattanooga. Before Buell could advance, General Braxton Bragg, the Confederate commander in Tennessee, suddenly invaded Kentucky. Buell raced to meet him, and the two armies clashed on October 8 at Perryville. Neither side won, but Bragg retreated to Murfreesboro, Tennessee.

Battle of Stones River

(or Battle of Murfreesboro). Lincoln felt that Buell was too cautious and replaced him with General William S. Rosecrans. Rosecrans advanced south from Nashville toward Bragg’s army at Murfreesboro on Stones River. The hard-fought battle dragged on from Dec. 31, 1862, to Jan. 2, 1863, when Bragg retreated. The battle had the highest casualty rate of the war, with each side losing about a third of its men.

The Vicksburg campaign.

In the winter of 1862-1863, Grant proposed to capture Vicksburg, the key city that guarded the Mississippi River between Memphis and New Orleans. Grant tried several times to take Vicksburg by approaching from the north. But the ground north of the city was low and marshy, and the Union army bogged down. In April 1863, Grant launched a new plan. At night, Union gunboats and supply ships slipped past the Confederate artillery along the river and established a base south of the city. Grant’s troops then marched down the west side of the river and crossed over by ship to dry ground on the east side south of the city. In a brilliant campaign, Grant scattered Confederate forces in the field and drove toward Vicksburg. After direct attacks failed, he began a siege of the city in mid-May. Vicksburg finally surrendered on July 4, the day after the Southern defeat at Gettysburg.

Five days later, forces under General Nathaniel P. Banks took Port Hudson, Louisiana. The North controlled the Mississippi River, splitting the Confederacy in two.

The Tennessee campaign

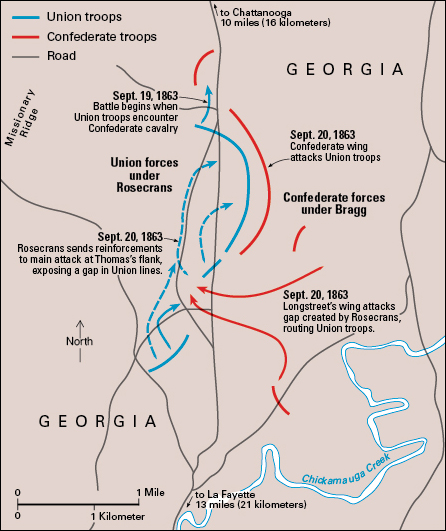

Battle of Chickamauga.

In September 1863, Rosecrans advanced on Chattanooga with a force of about 60,000 men. Bragg, who was seeking to keep his army free for action, evacuated the city and withdrew to Georgia. Rosecrans recklessly pursued him. Bragg had received reinforcements by rail from Virginia, and his forces numbered approximately 66,000. He fell on Rosecrans at Chickamauga, Georgia, on September 19 and 20. The Northern right flank broke completely. Only the Union left flank fought on under General George H. Thomas, who earned the nickname “The Rock of Chickamauga” for holding his line. In the end, Rosecrans’s entire army had to retreat to Chattanooga. The Battle of Chickamauga was the Confederacy’s last important victory in the Civil War.

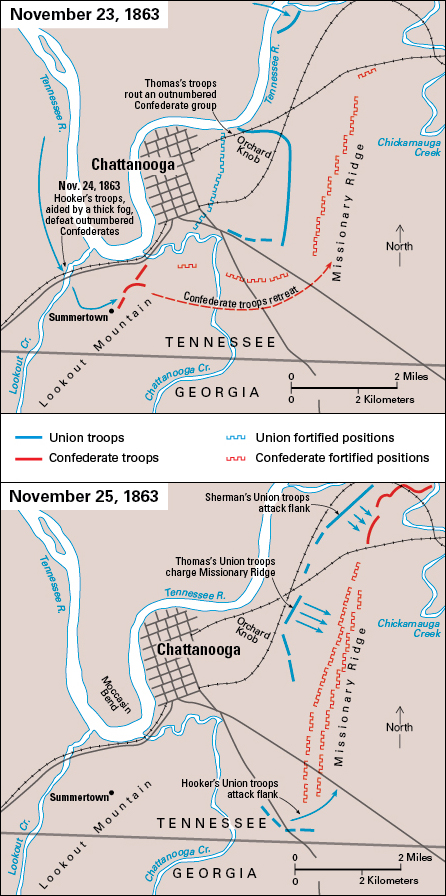

Battle of Chattanooga.

Bragg did not follow up his victory at Chickamauga immediately. In late September 1863, he finally advanced on Chattanooga. Bragg’s army occupied Lookout Mountain, Missionary Ridge, and other heights south of the city. From these points, Confederate artillery commanded the roads and the Tennessee River, by which Chattanooga received its supplies. Starvation threatened Rosecrans’s army. But the North had enough troops available in the West to meet any threat. In October 1863, Grant was given command of all Union forces in the West. He replaced Rosecrans with Thomas. Grant then went to Chattanooga with part of his own army.

From November 23 through 25, the Union troops dealt Bragg an immense blow in the Battle of Chattanooga. Lookout Mountain and some other heights fell on the first two days in the so-called Battle Above the Clouds. On November 25, Thomas’s army, anxious to make up for its defeat at Chickamauga, swept up Missionary Ridge without orders. The successful charge ended the Battle of Chattanooga in an hour. The Union had won Chattanooga. From that base, Northern armies could move into Georgia and Alabama and split the eastern Confederacy in two.

Behind the lines

Hospitals.

During the Civil War, many wounded and sick soldiers were treated in hospitals in Northern and Southern cities. But most received care in temporary facilities. Such facilities included field hospitals on or near battlegrounds, hospital ships and barges, and civilian buildings converted for medical use.

By today’s standards, the medical care was primitive. More than twice as many soldiers died of disease—especially of dysentery, malaria, or typhoid—as were killed in battle. Doctors did not yet understand the importance of sanitation, a balanced diet, and sterile medical equipment and facilities. But medical care within the military made some progress with the introduction of horse-drawn ambulances and a trained ambulance corps. The first such corps, begun in 1862, served under Union General McClellan.

Women performed a key role in providing medical care. Mary Walker served as a surgeon with the Union Army. She became the only woman ever to receive the Medal of Honor. Dorothea Dix, famous for her earlier work in mental institutions, was superintendent of U.S. Army nurses. Thousands of volunteer nurses served the Union and Confederate forces. One of the North’s volunteer nurses, Clara Barton, later founded the American Red Cross.

Private organizations also helped care for ill and wounded soldiers. One organization was the United States Sanitary Commission, created in June 1861. It operated hospitals and distributed food, clothing, medicine, and other supplies. The organization cared for both Union and Confederate soldiers.

Prisons.

About 194,000 Union soldiers and about 214,000 Confederate soldiers were held prisoner during the war. The North and the South had about 30 major prison camps each. Both sides also set up temporary prison quarters. Prison conditions were generally miserable because the camps were overcrowded and officials could not provide adequate care. In the South, where such necessities as food and clothing were in short supply for the Confederacy’s own soldiers and civilians, prisoners had an especially difficult time.

Andersonville, a Confederate camp in Georgia, became known as the worst of the prison camps. It was horribly overcrowded, and prisoners were deliberately abused and neglected. At Andersonville, as many as 32,000 Northern prisoners at a time were crowded into a log stockade designed to hold 10,000 people. After the war, the graves of nearly 13,000 Union prisoners were discovered there. The officer in charge of Andersonville, Henry Wirz, became the only Confederate soldier to be tried and executed for war crimes after the war.

At first, no official prisoner exchange took place between North and South. The Union government refused to extend such a degree of recognition to the Confederacy. A successful prisoner exchange agreement was reached by the middle of 1862. However, the agreement broke down in 1863, chiefly because the Confederacy resented the Union’s use of Black soldiers and refused to treat them as prisoners of war. After the Confederate government itself authorized the use of Black soldiers in 1865, large-scale prisoner exchange started again.

The final year—1864-1865

All signs pointed to victory for the Union in early 1864. The Southern armies had dwindled because of battle losses, war weariness, and Northern occupation of large areas of the Confederacy. Southern railroads had almost stopped running, and supplies were desperately short. But the South, still capable of tough resistance, fought on for over a year before surrendering.

Grant in command

Since 1862, Lincoln had wanted the Union armies to have a unified command and a coordinated strategy. Lincoln favored a cordon offense—a strategy in which the Union armies would advance on all fronts, pitting the vast Northern resources against the South. In Ulysses S. Grant, Lincoln felt that he had finally found the leadership needed to carry out such an offensive.

On March 9, 1864, Lincoln promoted Grant to lieutenant general and gave him command of all Northern armies. Grant planned three main offensives. The Army of the Potomac, under Meade, would try to defeat Lee in northern Virginia and occupy Richmond. Grant intended to accompany and direct that army. An army under General William T. Sherman would advance from Chattanooga into Georgia and seize Atlanta. Banks would move his men from New Orleans to Mobile, Alabama, and later join Sherman. The third offensive never developed because of a crushing defeat suffered by Banks on April 9 in a battle at Pleasant Hill, Louisiana.

Battle of the Wilderness.

In May 1864, the Army of the Potomac moved into a desolate area of northern Virginia called the Wilderness. Grant, with about 120,000 men, planned to march through the Wilderness and force the Confederates into a battle that would have a clear winner. Lee, with only about 62,000 troops, met Grant on May 5, and the Battle of the Wilderness raged for two days. Troops stumbled blindly through the forest, where cavalry proved useless and artillery did little good. The underbrush caught fire, and wounded men died screaming in the flames. Both sides suffered heavy losses, and neither could claim it had won.

Battle of Spotsylvania Court House.

In spite of his losses, Grant was determined to push on to final victory or defeat. He moved off to his left toward Richmond. Lee marched to meet him, and the great opponents clashed again at Spotsylvania Court House, Virginia, on May 8 through 19, 1864. Spotsylvania, like the Wilderness, brought large losses but no victory for either side.

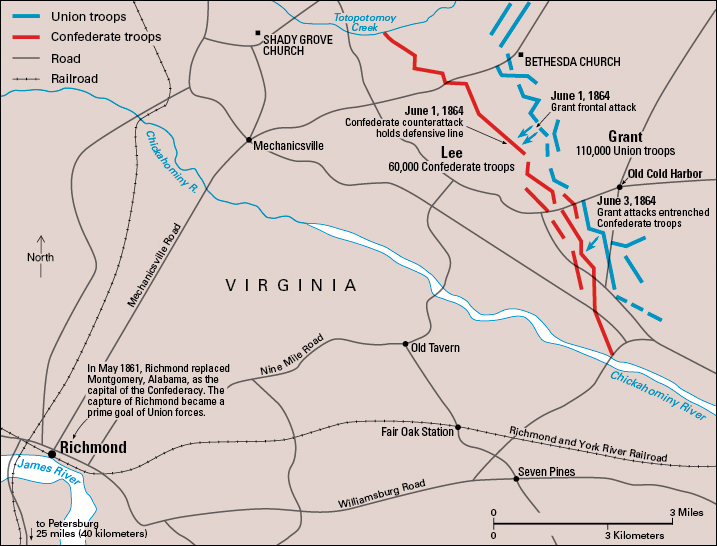

Battle of Cold Harbor.

Grant again moved off to his left toward Richmond, and again Lee marched to meet him. By June 1, 1864, Grant had reached Cold Harbor, a crossroads just north of the Confederate capital. There, on June 3, he made another attempt to smash Lee. About 50,000 attackers faced 30,000 defenders in trenches across a 3-mile (5-kilometer) line. Northern troops charged in a frontal assault. Gunfire cut down thousands of the advancing troops, many of them in the first minutes of the charge. Grant later said, “I regret this assault more than any one I have ever ordered.”

Cold Harbor forced Grant to change his strategy. Lee had shown superb defensive skill, and Northern losses had been enormous. In a month of fighting, Grant had lost almost 40,000 men. Newspapers began to call him “butcher Grant.” Grant felt that if he repeated his moves, Lee would fall back to the Richmond defenses, where the Confederates could hold out against a siege. Grant therefore made one more attempt to force a quick and final win-or-lose battle.

Siege of Petersburg.

Concealing his movement from Lee, Grant marched south and crossed the James River. His soldiers built pontoon (floating) bridges across the river. Grant then advanced on Petersburg, a rail center south of Richmond. All railroads supplying Richmond ran through Petersburg. If Grant could seize the railroads, he could force Lee to fight in the open. But a small Confederate force under Beauregard held him off until Lee arrived. Grant then realized that he could not destroy Lee’s army without a siege. His men dug trenches around the city. Lee’s weary troops did the same. The deadly siege of Petersburg began on June 20, 1864. It lasted more than nine months, until the Confederate troops withdrew near the war’s end.

Cavalry maneuvers.

While Grant was moving toward Richmond, he had sent his cavalry ahead under Sheridan to attack the city’s communications. Confederate cavalry led by General Jeb Stuart opposed Sheridan. The two forces met at Yellow Tavern, Virginia, on May 11, 1864. Stuart was fatally wounded in the battle.

In June, Lee sent an infantry force under General Jubal A. Early through the Shenandoah Valley to raid Washington, D.C. He hoped that Grant would send some of his troops to guard the Northern capital. Early attacked one of the forts on the outskirts of the city. Lincoln stood on a low wall atop the fort and watched the attack as bullets spattered around him. Early was not strong enough to take the capital and retreated to Virginia. But he remained a threat in the valley.

Although the Confederates could not take Washington, their ability to threaten the capital after three years of war weakened Northern morale. Grant thus put all Union forces in the Shenandoah Valley under Sheridan and ordered him to follow Early to the death. Sheridan’s forces outnumbered the Confederates 2 to 1 and drove them from the valley in a series of victories. His greatest success came at Cedar Creek, Virginia, on Oct. 19, 1864, when Early made a surprise attack while Sheridan was returning from a conference in Washington. Riding to the field from nearby Winchester, Sheridan rallied his men and won the battle. Sheridan then laid waste to the valley to flush out ambushers and to prevent its resources from being used by any Confederate army that might try again to attack Washington.

Battle of Mobile Bay.

The North’s blockade of Southern ports grew more effective. Union forces worked steadily to seize the main ports still open to ships that slipped through the blockade. In August 1864, a naval squadron under Farragut sailed into the bay at Mobile, Alabama, which was defended by forts; mines (then called torpedoes); gunboats; and an ironclad. After the Union lead ship, an ironclad, was blown up, Farragut ordered his own wooden commander’s ship, the Hartford, into the lead. “Damn the torpedoes! Full speed ahead!” was the cry he reportedly bellowed. The Union sailors captured the forts and took control of the bay, though they did not occupy Mobile. In February 1865, another main port, Wilmington, North Carolina, fell to Northern ships. But Charleston, South Carolina, still held out.

Closing in

The Atlanta campaign.

In May 1864, while Grant drove into the Wilderness, Sherman’s army of about 100,000 men advanced on Atlanta, Georgia, from Chattanooga. General Joseph E. Johnston opposed him with a force of about 60,000. Johnston planned to delay Sherman and draw him away from his base. The Atlanta campaign developed into a gigantic chess game. Sherman repeatedly moved forward, trying to trap Johnston into battling on open ground. Each time, Johnston and his troops slipped away into prepared trench positions. The two armies clashed frequently in small battles. The largest battle occurred on June 27 at Kennesaw Mountain, an isolated peak near Atlanta.

As Sherman reached the outskirts of Atlanta, Confederate President Davis, perhaps more for political than military reasons, decided Johnston was fighting too cautiously. He replaced him with General John B. Hood. Hood attacked the Union columns as Sherman approached Atlanta. But Hood’s attacks failed, and he took up a position in the city. Sherman first tried siege operations. But because he did not want to be delayed, he wheeled part of his army south of Atlanta and seized its only railroad to cut Hood’s supply line. Hood evacuated the city on Sept. 1, 1864. Sherman occupied it the next day.

North to Nashville.

Sherman’s victory was not as complete as it seemed. Hood’s army had escaped and begun hit-and-run raids on Sherman’s railroad communications with Chattanooga. Sherman thought it would be useless to chase Hood along the railroad. Instead, he sent General George H. Thomas back to Tennessee to take command and gave him some 32,000 men under General John M. Schofield. He ordered Thomas, at Nashville, to assemble more troops in Tennessee and keep Hood out of the state. With his remaining men, Sherman planned to cross Georgia to Savannah, near the Atlantic coast.

Hood boldly decided to invade Tennessee in the hope that Sherman would follow him. He felt sure that he could beat Sherman in the mountains. He would then either invade Kentucky or cross into Virginia and join Lee. But Hood’s plan was too big for his army.

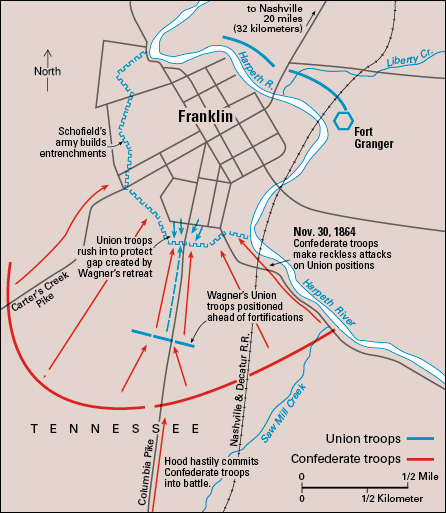

Battle of Franklin.

Hood might have won a partial success if he had moved into Tennessee immediately. But he delayed and met Schofield’s force at Franklin, Tennessee, on Nov. 30, 1864. Hood, an aggressive commander, had complained that his army had retreated so much under Johnston that it had forgotten how to attack. His generals seemed determined to prove him wrong. In six reckless charges, the Confederates suffered about 6,300 casualties, including 6 generals killed.

Battle of Nashville.

Hood had no chance of success after his defeat at Franklin. He took a position south of Nashville and waited. In the city, Thomas had time to gather an army of about 55,000. He attacked Hood on Dec. 15 and 16, 1864, and won one of the biggest victories of the war. The Confederates made a bitter retreat to Mississippi.

Sherman’s march through Georgia

began on Nov. 15, 1864, when he left Atlanta in flames. His army, numbering about 62,000 men, swept almost unopposed on a 50-mile (80-kilometer) front across the state. Advance troops scouted an area. The men who followed stripped houses, barns, and fields and destroyed everything they could not use. Sherman hoped the horrible destruction would break the South’s will to continue the war.

Sherman occupied Savannah on December 21 and sent a message to Lincoln: “I beg to present to you as a Christmas gift the city of Savannah with 150 heavy guns and plenty of ammunition and also about 25,000 bales of cotton.” From Savannah, Sherman swung north into South Carolina. There, on the breeding ground of the Southern independence movement, his army seemed bent on revenge. They burned and looted on a scale even worse than in Georgia. When Charleston surrendered, it was spared. Although Sherman tried to prevent it, most of Columbia, the state capital, was burned.

Sherman and his troops then moved on into North Carolina. Johnston tried to oppose them, but he had only one-third as many men. The Northerners drove on toward Virginia to link up with Grant.

The South surrenders.

In Virginia, Grant at last achieved his goal. In April 1865, he seized the railroads supplying Richmond. The Confederate troops had to evacuate Petersburg and Richmond. Lee retreated westward with nearly 50,000 men. He hoped to join forces with Johnston in North Carolina. But Grant overtook him and barred his way with an army of almost 113,000 troops. Lee realized that continued fighting would mean useless loss of lives. He wrote Grant and asked for an interview to arrange surrender terms.

On April 9, 1865, the two great generals met in a house owned by a Southern farmer named Wilmer McLean in the little country settlement of Appomattox Court House, Virginia. The meeting was one of the most dramatic scenes in American history. Grant wore a mud-spattered private’s coat, with only his shoulder straps indicating his rank. Lee had put on a spotless uniform, complete with sword. Grant offered generous terms, and Lee accepted them with deep appreciation. The Confederate soldiers received a day’s rations and were released on parole. They were allowed to keep their horses and mules to take home “to put in a crop.” Officers could keep their side arms.

Five days later, on the evening of April 14, Lincoln was shot by Southern sympathizer John Wilkes Booth. He died the following morning. Northerners cried out for revenge for Lincoln’s assassination and for the hundreds of thousands killed in the war. But before his death, Lincoln had advised “malice toward none … charity for all’’ to heal the country’s wounds. Although feelings were strong, no major incidents occurred.

With Lee’s army gone, Johnston surrendered to Sherman on April 26 near Durham, North Carolina. Confederate President Davis fled southward and was captured in Georgia. General Richard Taylor surrendered the Confederate forces in Alabama and Mississippi on May 4. The war’s last battle took place at Palmito Ranch, near the southern tip of Texas, on May 13. The Confederate and Union soldiers fighting there did not know that the South had surrendered. On May 26, General Edmund Kirby Smith surrendered the last Confederate army still in the field. The war was over.

Results of the war

The tragic costs.

According to most accounts, about 620,000 soldiers died during the Civil War. This figure is almost as many as the combined American dead of all other wars from the American Revolution (1775-1783) through the Iraq War (2003-2011). The Union lost about 360,000 troops, and the Confederacy about 260,000. Disease caused more than half the deaths. About a third of all Southern soldiers died in the war, compared with about a sixth of all Northern soldiers.

In the 2010’s, studies based on United States census data suggested that the war’s losses had been undercounted. The studies estimated that at least 750,000 men died as a result of the Civil War. The figure includes civilians killed in guerrilla warfare. It also includes troops who died as a result of war wounds or disease in the years immediately following the war.

Both the North and the South paid an enormous economic price as well. But the direct damages caused by the war were especially severe in the South. The destruction in the South extended from the beautiful Shenandoah Valley in the north to Georgia in the south and from South Carolina in the east to Tennessee in the west. Towns and farms, industry and trade, and the lives of men, women, and children were ruined throughout the South. The whole Southern way of life was lost.

Terrible bitterness between the people of the North and South followed the war and continued for generations. The South was given almost no voice in the social, political, and cultural affairs of the nation. With the loss of Southern control of the national government, the more traditional Southern ideals no longer had an important influence over government policy. The Yankee Protestant ideals of the North became the standard for the United States. However, those ideals, which stressed hard work, education, and economic freedom, helped encourage the development of the United States as a modern, industrial power.

The beginning of modern warfare.

The American Civil War is frequently called the first modern war. It was the first war in which the participants communicated by telegraph, transported supplies and troops by train, and used ironclad warships, submarines, and mines in naval combat. The armies were much larger than armies of the past. These forces introduced trench warfare and other combat tactics used in later wars.

On the other hand, the muzzleloading rifles and cannons used by most of the soldiers were soon surpassed by more advanced weapons and artillery. The ironclad warships gave way to warships of steel.

The American Civil War is also often described as the first total war because of the enormous amount of suffering and destruction it brought upon noncombatants as well as soldiers. A military campaign such as Sherman’s march seemed to indicate a shift from war as a battle between two armies to war as systematic destruction of anyone and anything in an army’s path. However, little of the war’s destructiveness was the result of deliberate planning, even during Sherman’s march. The war destroyed much of the South and ruined Southern agriculture. But the North never experienced a serious invasion, though large sectors of its economy suffered.

Union and Confederate leaders alike struggled to observe the accepted rules and conventions of war. They failed in the treatment of prisoners of war, but most of the evils of the prison system arose from incompetence and poor planning. Neither side resorted to executing all prisoners, though Confederates did execute some captured Black soldiers. After the war, the federal government did not seek to convict the defeated Confederates of treason. In the end, if the Civil War can be considered a total war, it is because the conflict, with its huge armies and four years of fighting in two theaters of war, destroyed so many lives and so much of the nation’s resources.

The end of slavery.

The Declaration of Independence, which gave birth to the United States in 1776, stated that “all men are created equal.” Yet the United States continued to be the largest slaveholding nation in the world until the Civil War. Americans tried to make equality a reality soon after the war by ratifying (approving) the 13th Amendment to the Constitution, which officially abolished slavery throughout the United States. The place of Black citizens in American society, however, remained unsettled.