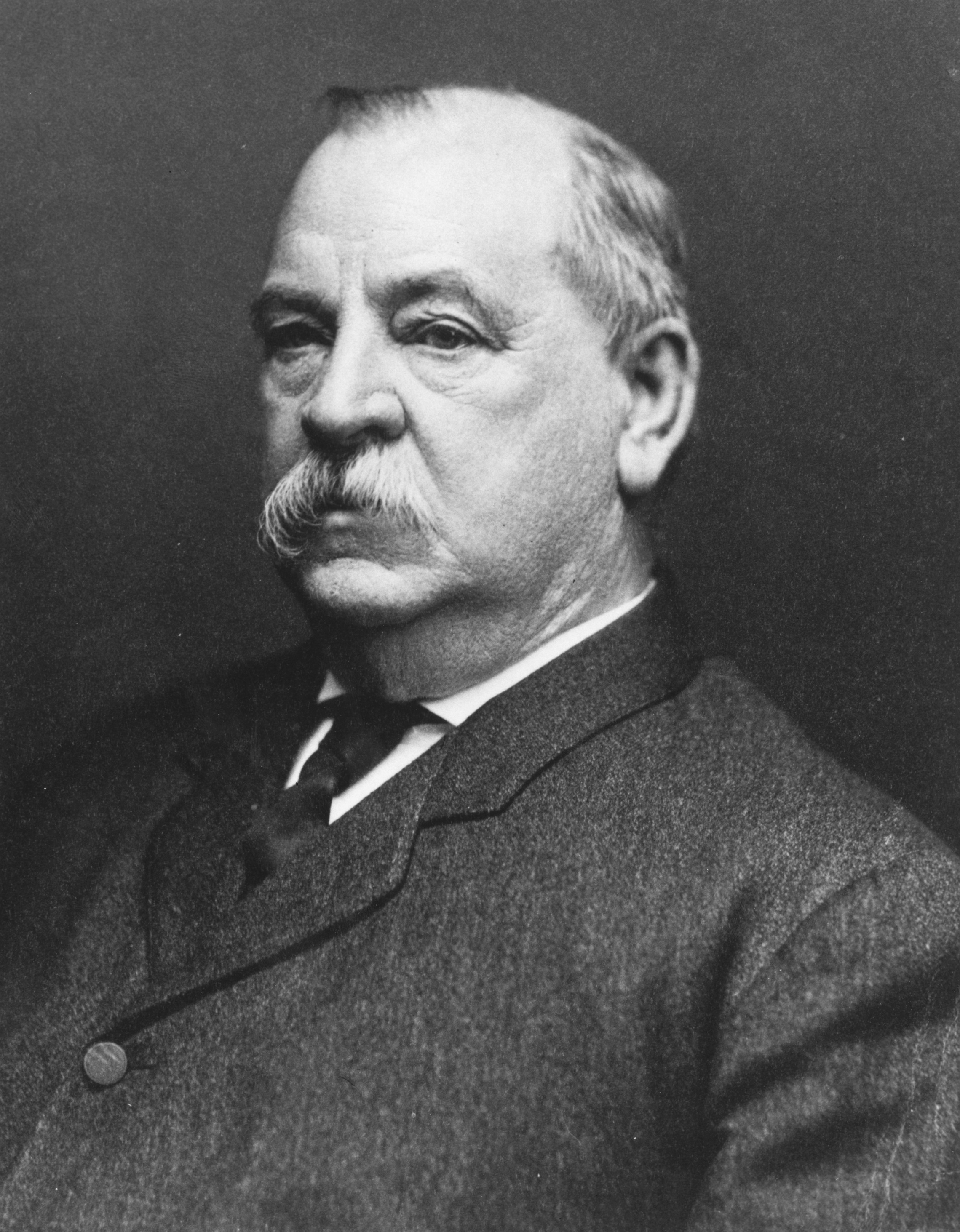

Cleveland, Grover (1837-1908), was the only president who served two terms that did not directly follow each other. He won the presidency in 1884, but lost it four years later to Benjamin Harrison. He ran against Harrison again in 1892 and won a second term.

Cleveland was the first Democratic president elected after the American Civil War (1861-1865). This very fact showed that wartime issues had lost some of their force in defining party loyalties. Cleveland’s victory also was a protest against the politics-as-usual of the spoils system. His honesty and common sense helped restore confidence in the government. These qualities had served him in his earlier successes as a lawyer, sheriff, and mayor, and as governor of New York.

As president, Cleveland had the courage to say “No.” He said it often—to farmers who sought easy money to pay their debts, to manufacturers who wanted high protective tariffs, and to veterans who wanted looser requirements for getting a pension. These “No’s” made Cleveland unpopular in his time, but have added to the respect with which history holds him.

This big, good-humored man, called “Uncle Jumbo” by his relatives, occupied the White House during a time of swift social and economic change. The growing strength of labor unions and farm organizations created new problems for government. Cleveland lacked the experience and vision to find completely satisfactory answers to all the problems. In 1894, he attempted to settle a labor strike by force—the legal force of court injunctions and the physical force of army troops. Cleveland clung steadfastly to his faith in “sound” money and a low tariff as a cure for the nation’s other economic ills. Although Cleveland’s intentions were good, his methods fell short of success.

The era of the western frontier was drawing to a close when Cleveland took office. Settlers in the southwestern United States breathed easier when federal troops captured the Apache warrior Geronimo. Jacob Riis shocked a complacent public with newspaper stories of how “the other half” lived in rundown slums.

During Cleveland’s second term, the Duryea brothers built America’s first automobile. A Kansas preacher, Charles M. Sheldon, wrote In His Steps (1896), one of the world’s all-time best sellers. Americans of the Gay Nineties enjoyed Victor Herbert’s early operettas. At the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, they applauded John Philip Sousa’s band and rode the first Ferris wheel ever built. But it was also a time of great hardship. The urban poor lived crowded together in slums. A depression slowed the economy to a near standstill, and unemployment soared.

Early life

Boyhood.

Stephen Grover Cleveland was born on March 18, 1837, in Caldwell, New Jersey. He dropped his first name while still a boy. Grover was the fifth child in a family of four brothers and five sisters. His father, Richard Falley Cleveland, was a Presbyterian minister and a relative of Moses Cleaveland, the founder of Cleveland, Ohio. His mother, Ann Neal Cleveland, was the daughter of a publisher.

The family of a country minister led a hard life. The Clevelands had little money and moved often. Grover attended schools in Fayetteville and Clinton, New York, and went to work at the age of 14 as a clerk in a Fayetteville general store. He was only 16 when his father died, leaving him and his brothers to support his mother and sisters. Cleveland joined an older brother who was teaching at the New York Institution for the Blind in New York City. He taught there for a year.

Lawyer.

When Cleveland was 17, he decided to go west to look for better opportunities. He planned to settle in Cleveland, Ohio, which attracted him because of its name. But he stopped in Buffalo, New York, to visit his mother’s uncle, Lewis F. Allen, who persuaded him to stay there. Grover worked for his uncle for six months, then decided to become a lawyer. He worked as a clerk in the law office of Rogers, Bowen, and Rogers, and studied there. The serious, quiet youth worked hard for his $4 a week, which paid for room and board at the home of a fellow law clerk.

After being admitted to the bar in 1859, Cleveland continued to work for the same law firm. Two of his brothers served in the Union Army during the Civil War, but Cleveland’s help was needed to support his mother and the other children. He paid a substitute to take his place in the army. Although this was legal and a common practice, the fact that he had not served in the war was later used against him by his political enemies.

Political career

Minor offices.

Cleveland entered politics as a ward worker for the Democratic Party in Buffalo. He served as ward supervisor in 1862 and later as assistant district attorney of Erie County. He was elected sheriff in 1870. During his term, the county had to hang two convicted murderers. Most sheriffs had delegated this distasteful task to deputies, but Cleveland sprang the traps himself. He explained that he would not ask anyone else to do what he was unwilling to do.

Cleveland returned to the practice of law after three years as sheriff. He relaxed by hunting and fishing with fellow lawyers. To relatives who wondered whether their stout “Uncle Jumbo” had ever thought of marrying, he replied: “A good many times; and the more I think of it the more I think I’ll not do it.”

Mayor of Buffalo.

Like many cities, Buffalo suffered from a corrupt administration. In response to a growing demand for reform, Democratic leaders chose Cleveland to run for mayor in 1881. He won the election, and gave his political backers more reform than they had bargained for. Cleveland vetoed so many padded city contracts that he became known as the “veto mayor.”

Governor of New York.

Cleveland’s reputation for honest administration became a valuable political asset. The Democrats nominated him for governor in 1882 as a candidate not owned by any political faction. He won easily.

Cleveland gave New York the same conscientious administration he had given Buffalo. He vetoed padded appropriation bills regardless of political pressure. He aroused a storm of protest when he killed a bill that would have lowered streetcar fares in New York City. Cleveland explained that the bill violated the terms of a previous transit contract. Theodore Roosevelt, then a member of the state legislature, had advocated the bill but later admitted that Cleveland had been right. When Cleveland later cooperated with Roosevelt to pass laws reforming the government of New York City, he earned the undying hatred of Tammany Hall, the Democratic political machine that controlled the city.

Election of 1884.

Cleveland’s reputation for good government made him a national figure. The Republican Party nominated James G. Blaine for president in 1884, even though he had been implicated in a financial scandal. Many influential Republicans were outraged. They thought the time had come for a national reform administration. These Republicans, called mugwumps, withdrew their support for the ticket and declared that they would vote for the Democratic candidate if he were an honest man. The Democrats answered by nominating Cleveland. They chose Thomas A. Hendricks, a former governor of Indiana, for vice president.

Good political issues were available to both parties in the campaign. Farmers were growing poorer, private interests were grabbing public lands and resources, and labor was becoming more dissatisfied. But neither party faced these issues. Instead, each attacked the other’s nominee with scandalous personal stories. Republican-leaning newspapers published an unverified account of Cleveland fathering a child out of wedlock 10 years earlier. During some rallies, Republican crowds highlighted the scandal with the chant, “Ma! Ma! Where’s my pa?”

A series of campaign blunders by Blaine turned the tide. One of the most costly mistakes was made by a supporter of Blaine at a Republican rally in New York City. Samuel D. Burchard, a Presbyterian clergyman, declared that a vote for Cleveland would be a vote for “rum, Romanism, and rebellion.” This remark appealed to popular prejudices that linked the Democrats with whiskey, Roman Catholicism, and the Southern cause in the Civil War. Roman Catholics deeply resented the statement. Blaine later repudiated it, but the damage had been done. Cleveland, by 25,685 votes, became the first Democratic president to be elected since James Buchanan in 1856.

First Administration (1885-1889)

Cleveland, who faced a Republican Senate, made effective use of the presidential powers of veto, appointment, and administrative control. With these weapons, rather than with any strong legislative program, he moved to restore government efficiency.

Reforms.

Cleveland ordered the members of his Cabinet to eliminate “abuses and extravagances” in their departments. As a result, the Department of the Navy tightened its supervision of shipbuilding and added several new vessels to the fleet, including the battleship Maine.

The Department of the Interior forced western railroads to return to the public domain vast acreages of excess right-of-way land that the railroads had held illegally. This land was forfeited because the railroads had failed to carry out their earlier agreements to extend their lines. The forfeited land equaled the combined areas of New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, and Virginia.

The spoils system had continued to flourish in spite of the Civil Service Act of 1883. Cleveland, like other presidents of his era, was besieged by office seekers. He tried to steer a middle course between the reformers, who wanted him to extend civil service, and party politicians, who were hungry for jobs. He more than doubled the number of workers who held jobs through the merit system, although the total still included fewer than a fourth of all government employees. But his moderation satisfied neither the reformers nor the politicians.

Labor problems

were among Cleveland’s gravest concerns. Farmers had heavy debts, and the Grange and Farmers’ Alliances demanded reforms. Laborers suffered from low wages and harsh working conditions. Employers in those days felt little sense of responsibility for their employees. The Knights of Labor, a labor group, grew to 700,000 members by 1886. This labor group’s strike at the McCormick-Harvester plant in Chicago led indirectly to the bloody Haymarket Riot.

Cleveland distrusted workers’ movements, but he acted for the best interests of the nation as he saw them. He was the first president to devote an entire congressional message to the labor issue, although nothing came of his proposal for a permanent government arbitration board.

Veterans’ affairs.

Cleveland opposed many pension measures, defying the Grand Army of the Republic and other pressure groups. The pension rolls had become full of fraud. Many healthy veterans claimed to be unfit for work, and widows continued to collect government money after they had remarried. Cleveland vetoed the claims of hundreds of people he felt were undeserving.

Cleveland also vetoed the Dependent Pension Bill, which would have extended pension coverage to all disabled veterans, whether or not their disabilities were related to military service. This bill later passed in 1890.

The currency and the tariff

were the most important issues facing Cleveland during his first term. Dissension was growing between the bankers and industrialists of the East, and the farmers of the South and West. The industrialists wanted a high tariff to protect high prices. They also wanted what they called a “sound” money system, based on gold. Farmers wanted a low tariff so they would not have to pay high prices for imported manufactured goods. They had heavy debts, and wanted money to be “cheap” in comparison with goods. That is, the farmers wanted inflation, so they could pay their debts with less farm produce.

The currency

of the United States at this time was based on gold. But the Bland-Allison Act of 1878 required the Treasury to buy and coin at least $2 million worth of silver a month. The coins were minted on a standard that made 16 ounces (496 grams) of silver equal in value to 1 ounce (31 grams) of gold. Meanwhile, new silver mines had been discovered, and the world price of silver fell. Since the actual value of a silver dollar was less than that of a gold dollar, people exchanged their silver dollars for gold dollars. As a result, gold was drained from the Treasury.

Cleveland believed in a gold standard. He asked Congress to repeal the Bland-Allison Act, but it refused. The government then issued bonds and sold them to banks for gold. But this helped matters for only a short time, because the drain on the Treasury’s gold continued.

The tariff.

Cleveland felt that tariffs should be reduced, mainly because the government was collecting more money than it spent. His supporters advised him not to bring up this controversial subject. But, in his annual message in 1887, he dared to ask Congress to lower tariffs. Congress failed to pass a tariff reduction, but Cleveland focused national opinion on this problem.

Other actions.

The Presidential Succession Act of 1886 settled questions regarding succession to the presidency. One of the most important bills of Cleveland’s first term was the Interstate Commerce Act of 1887. This act allowed the federal government to regulate interstate railroads.

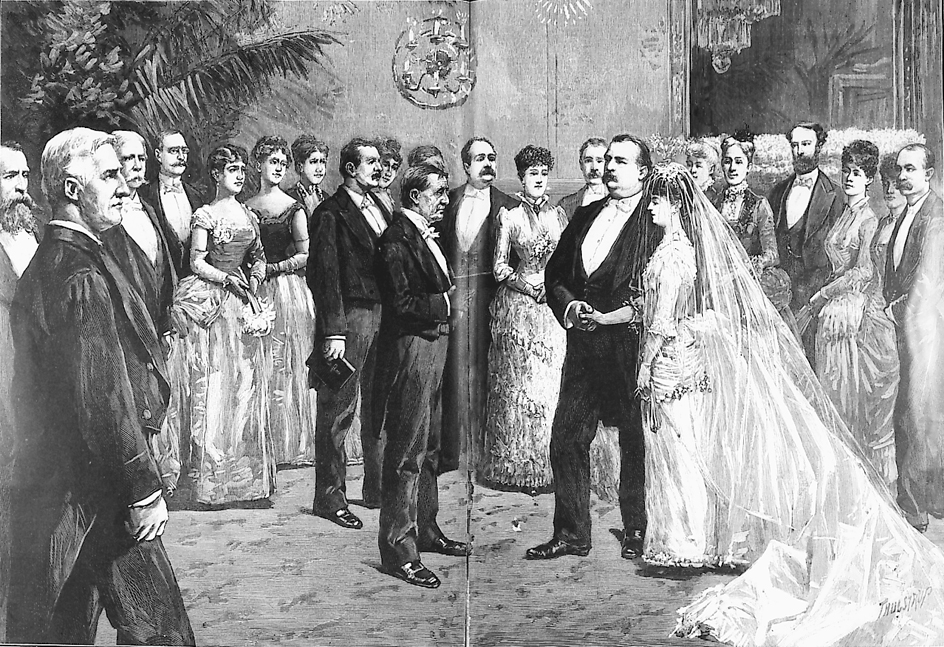

Cleveland’s family.

In June 1886, Cleveland delighted the nation with his marriage to Frances Folsom (July 21, 1864-Oct. 29, 1947). The 21-year-old bride was the daughter of one of Cleveland’s law partners, who had died in 1875. Cleveland was the only president to be married in the White House, and reporters pried into every detail with what he called “colossal impertinence.”

The Clevelands had five children: Ruth (1891-1904), Esther (1893-1980), Marion (1895-1977), Richard F. (1897-1974), and Francis (1903-1995). Esther Cleveland was the first and only child of a president to be born in the White House.

Five years after Cleveland’s death, Mrs. Cleveland married Thomas J. Preston, Jr., a Princeton professor.

Life in the White House.

During Cleveland’s first year in office, his younger sister Rose acted as his hostess. After his marriage, his young wife performed these official duties with ease and charm.

Cleveland was a hard-working president, particularly because he was unwilling to delegate responsibility. “He would rather do something badly for himself than have somebody else do it well,” grumbled a political colleague. The president often stayed up until 2 or 3 A.M. going over official business, and sometimes answered the White House telephone himself.

As the Clevelands left the White House in 1889, Mrs. Cleveland told the servants: “I want you to take good care of all the furniture and ornaments in the house, for I want to find everything just as it is now when we come back again … four years from today.”

Election of 1888.

The tariff became the main issue in the election of 1888. Benjamin Harrison, the Republican candidate, opposed tariff reduction. Neither Cleveland nor the Democratic Party waged a strong campaign. Cleveland’s attitude toward the spoils system had antagonized party politicians. His policies on pensions, the currency, and tariff reform had made enemies among veterans, farmers, and industrialists. Even with these enemies, Cleveland had more popular votes than Harrison. However, Harrison received a larger electoral vote and won the election. See Harrison, Benjamin (Election of 1888).

Between terms

New York attorney.

Cleveland moved to New York City in 1889 and returned to the practice of law. The Harrison Administration reversed many of Cleveland’s stringent policies. It boosted the tariff, increased the purchase of silver, and extended pension coverage. Both prices and government expenditures reached new heights. Cleveland, on the sidelines, sharply criticized Harrison’s program.

Election of 1892.

By the end of Harrison’s term, many Americans were ready to return to Cleveland’s harder policies. In 1892, the Democratic National Convention nominated Cleveland and chose Adlai E. Stevenson, a former Illinois congressman, as his running mate. The Republicans renominated Harrison and nominated Whitelaw Reid for vice president.

The campaign centered mainly on economic unrest and what the Democrats called Republican misrule. The new Populist Party, formed by groups from the Grange, the Farmers’ Alliances, and the Knights of Labor, polled more than a million votes. But Cleveland won easily.

Second Administration (1893-1897)

Cleveland was more popular at the beginning of his second term than at any other time during his presidency. He had made no promises to anyone to become president again. He was free to handle the country’s problems as he saw fit, with Democratic majorities in both houses of Congress. But a severe financial panic swept the country only two months after he took office. Its causes included a farm depression, a business slump abroad, and the drain on the Treasury’s gold reserve.

At this crucial time, physicians found that Cleveland had cancer of the mouth. Government leaders feared that the nation’s shaky financial situation would become worse if the public knew of the president’s illness. To keep it a secret, Cleveland boarded a friend’s yacht in New York Harbor in July, and a team of surgeons removed his left upper jaw while the ship steamed up the East River. The operation was completely successful. Cleveland wore an artificial jaw made of rubber, which changed his appearance only slightly. News of the operation gradually became public, although great efforts were made to keep it secret.

Labor unrest

grew more serious with the business slump. Cleveland was not hostile to labor. But his strong belief in order and his limited understanding of changing conditions led him to use force rather than to seek constructive solutions to the new problems that faced his Administration.

One sign of discontent was “Coxey‘s Army,” a group of unemployed men who demonstrated for government aid. Coxey’s marchers got a cool reception from Cleveland. Unwilling to act for the jobless, Cleveland appeared eager to act against strikers. The Pullman Strike of May 1894 had a great effect on the nation. Workers of the Pullman Company went on strike, and members of the American Railway Union, led by Eugene V. Debs, supported them by refusing to handle Pullman cars. A general railroad strike resulted. A federal court issued an injunction against the strikers because mail service had been interrupted. Disorders broke out near Chicago, and Cleveland sent federal troops, saying: “If it takes the entire army and navy of the United States to deliver a postal card in Chicago, that card will be delivered.” The government broke the strike. Most people approved Cleveland’s action. But Governor John P. Altgeld of Illinois, who had state militia standing ready to take action, argued that the disorders were not serious enough to warrant federal troops. Some historians believe that Cleveland exceeded his constitutional powers and violated states’ rights.

Tariff defeat.

Cleveland resumed his campaign for tariff reform and again asked Congress to lower import duties. While the Wilson-Gorman bill was being debated, the president issued a statement accusing uncooperative Democrats of “party perfidy and party dishonor.” His comments outraged many party members, and the bill as passed in 1894 fell far short of Cleveland’s goal. The bill also provided for a federal income tax. Disappointed, Cleveland let it become law without his signature because it also provided for a federal income tax. The Supreme Court later declared the income tax provision unconstitutional.

Foreign affairs.

Many Americans in the 1890’s felt that the United States should build a colonial empire. Cleveland wanted the United States to respect the rights of smaller, weaker nations. Events in Hawaii and Venezuela tested his principles.

Hawaii.

At the end of Benjamin Harrison’s Administration, American settlers in Hawaii had brought about a revolution and asked the United States to annex the islands. Cleveland’s second term began before the Senate could ratify the treaty of annexation. Cleveland felt that Americans in Hawaii had involved the United States in a dishonorable action, and he withdrew the treaty from the Senate. Hawaii continued independent until 1898.

Venezuela.

Cleveland’s most popular action during his second term was his firm stand in a boundary dispute between the United Kingdom and Venezuela. The United Kingdom had refused for several years to allow its claim to be decided by a board of arbitration. In 1895, Secretary of State Richard Olney sent a sharp note to the British declaring that “the United States is practically sovereign on this continent, and its fiat is law upon the subjects to which it confines its interposition.” In a message to Congress, Cleveland hinted that armed force might be necessary to settle the matter. The British agreed to submit the Venezuela boundary to international arbitration, and a settlement was reached in 1899. But historians have criticized Cleveland’s intervention as extreme and provocative.

Saving the gold standard.

A severe financial panic in 1893 caused 15,000 business failures and threw 4 million people out of work. Cleveland felt that a basic cause of the panic was the Sherman Silver Purchase Act of Harrison’s Administration. In June 1893, he called a special session of Congress to repeal the act. Congress did so, but the nation’s gold reserves had dwindled alarmingly. The repeal also caused less money to be in circulation than ever. Prices for farmers, already low, got lower. Cleveland’s insistence on the repeal tore his party apart and made the depression even worse. The government floated four bond issues in the next three years to replenish the gold reserves. J. P. Morgan and other financiers bought three of these bond issues, and Cleveland’s opponents charged that Cleveland had betrayed the nation to Eastern bankers.

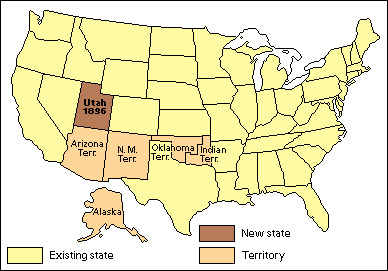

Meanwhile, the silver interests grew stronger. By the time of the Democratic convention in 1896, the “silverites” outnumbered the “goldbugs.” To the dismay of Cleveland, who did not seek a third term, William Jennings Bryan won the Democratic presidential nomination. Bryan’s famous “cross of gold” speech swung the party to the silver cause. Cleveland preferred the sound money policies of William McKinley, the Republican candidate. But Cleveland did not endorse McKinley and took no part in the campaign. Cleveland’s popularity had reached a low ebb at the end of his term, and he spoke of his “poor old battered name” when he left the White House in 1897.

Later years

Cleveland spent his last years in Princeton, New Jersey. Public opinion about him gradually changed, and he regained respect. He served Princeton University as lecturer and as trustee. He quarreled bitterly about university issues with Woodrow Wilson, the university’s president. Cleveland wrote several magazine articles, and in 1904 published some of his lectures under the title Presidential Problems. He also helped reorganize the Equitable Life Assurance Society after financial scandals had damaged its reputation. People believed so strongly in him that his name restored their confidence.

After a three-month illness, Cleveland died on June 24, 1908. His last words were: “I have tried so hard to do right.” Cleveland was buried in Princeton.