Columbus, Christopher (1451-1506), was an outstanding navigator and organizer of expeditions. He achieved fame by sailing across the Atlantic Ocean from Europe in search of a western sea route to Asia. However, he never accomplished this goal. Instead, in 1492, he encountered islands in the Caribbean Sea. Until that time, Europeans and Native Americans had not been aware of each other’s existence. During his four voyages westward, between 1492 and 1504, Columbus explored the Caribbean region and parts of Central and South America.

Columbus was not the first European to reach the Western Hemisphere. The Norse (also called the Vikings) had settled for a time on the coast of North America about A.D. 1000. But that contact did not last, and most Europeans of the 1400’s did not know it had taken place. Columbus’s voyages led to enduring links between the Eastern and Western hemispheres.

The world of Columbus

Early years

Boyhood.

The exact date of Columbus’s birth is not known. He was born sometime between Aug. 25 and Oct. 31, 1451, in Genoa, then the capital of a self-governing area on the northwest coast of Italy. Genoa was an important seaport with a long seafaring tradition, and its ships traded throughout the Mediterranean region.

Christopher’s given and family name was Cristoforo Colombo. In English, he is known as Christopher Columbus, the Latinized form of the name. He called himself Cristóbal Colón after he settled in Spain. His father, Domenico Colombo, was a wool weaver. To increase his modest income, Domenico also worked as a gatekeeper and wine merchant. Christopher’s mother, Susanna Fontanarossa, was the daughter of a wool weaver.

Christopher was the eldest of five children. His brothers, Bartholomew and Diego, worked closely with him on many of his enterprises. Christopher and his brothers may have been tutored or sent to a monastery school to learn basic Latin and mathematics, though Christopher’s formal education apparently ended at about age 14.

Young adulthood.

Christopher’s ambitious father pushed the boy into a business career, and Christopher began to sail on trading trips. He worked as an agent for the Spinolas, Di Negros, and Centuriones—powerful Genoese commercial families. In the mid-1470’s, in his first documented voyage, Columbus took part in a trading expedition to the island of Chios, a Genoese possession in the Aegean Sea. In 1476, he settled in a Genoese colony in Lisbon, Portugal. There is a legend that he reached Portugal by swimming ashore clinging to an oar after being attacked by pirates. In Lisbon, Columbus joined his brother Bartholomew to draw and sell maps.

Columbus often attended Mass at a chapel at the Convento dos Santos, a school for aristocratic young women. There, he met Felipa Perestrello Moniz, whom he married in 1479. Felipa’s father was the first governor of Porto Santo, a Portuguese island in the Madeira group off northern Africa’s Atlantic coast. The couple moved to Porto Santo, then to the nearby island of Madeira. Their only child, Diego, was born in 1480. Felipa died in 1484 or 1485.

Between 1480 and 1485, Columbus made several voyages to the Canary Islands and the Azores, island groups in the Atlantic Ocean west of Africa. Columbus also visited Portugal’s fortified trading posts in western Africa, where he observed the trade in gold and slaves. Some historians believe Columbus also went to England and Ireland, and even to Iceland, where he may have learned of early Norse explorations. On these voyages, Columbus gained experience of Atlantic wind systems.

The plan to sail westward

The basis of the plan.

By the 1480’s, the Portuguese had invented the caravel, a fast, sturdy ship that was better at sailing against the wind than traditional vessels were. They were trying to reach the Indies—what are now India, China, the East Indies (southeastern Asia), and Japan—by sailing around Africa. By doing this, they hoped to gain direct access to gold, silk, gems, and spices. The cloves, nutmeg, and mace of the Spice Islands (now the Moluccas of Indonesia) served as medicines as well as seasonings. These valuable items had been transported to Europe by means of dangerous and costly overland caravans that were often hindered by Ottoman officials. While Portuguese sailors were trying to reach Asia by sailing around Africa, Columbus proposed what he believed to be an easier route—sailing due west.

A map of the world made by Ptolemy, an astronomer and geographer in Alexandria, Egypt, in the A.D. 100’s, might have been the basis for Columbus’s notions of geography. Ptolemy’s map showed most of the world as covered by land. However, Columbus found confirmation for his idea of sailing west to Asia in the letters and charts of Paolo Toscanelli, an influential scholar from Florence, Italy. Toscanelli believed that Japan lay only 3,000 nautical miles (5,560 kilometers) west of the Canary Islands. Columbus planned to sail 2,400 nautical miles (4,500 kilometers) west along the latitude (distance from the equator) of the Canaries until he reached islands that supposedly lay east of Japan. There, he hoped to establish a trading town and base for further exploration.

Columbus’s plan was based in part on two major miscalculations. First, he underestimated the circumference of the world by about 25 percent. Columbus also mistakenly believed that most of the world consisted of land rather than water. This mistake led him to conclude that Asia extended much farther east than it actually did.

Presentation of the plan to Portugal.

About 1483, Columbus gained audiences with King John II of Portugal. The king placed Columbus’s proposal before his council, which rejected it. Columbus did not have to prove to the council that the world was round because educated people at that time knew it was. The council turned down his plan on the correct belief that he had greatly underestimated the length of the journey. The king’s advisers concluded that Portugal’s resources would be better invested in finding a route around Africa to Asia.

Years of waiting.

In 1485, Columbus and his son went to Spain, a bitter rival of Portugal. At that time, Spain consisted of the united kingdoms of Castile and Aragon. Columbus arrived during Spain’s war to drive the Muslims out of Granada, the only remaining Islamic kingdom on Spanish soil. Two wealthy Spanish aristocrats offered to give Columbus some ships. But to do so, they needed the permission of Spain’s King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella. In 1486, Columbus gained an interview with the monarchs, but they were in no position to finance an expedition at that time. They were also cautious about reopening conflict with Portugal. Spain and Portugal had recently settled their disputes over various islands off Africa. The Treaty of Alcaçovas, signed in 1479, had conceded the Canary Islands to Spain and the Madeira and Cape Verde islands and the Azores to Portugal.

Although they were cautious, the Spanish monarchs were nevertheless willing to consider a plan that could give them an advantage over Portugal in the race for Asia. Columbus also appealed to the intensely religious monarchs by vowing to use the proceeds from his expedition in the recapture of Jerusalem from the Muslims. There, he said, he would rebuild the Jews’ holy Temple and bring on a new “Age of the Holy Spirit.”

Queen Isabella was about the same age as Columbus, and she admired men of conviction. At her insistence, Columbus’s plan was put before a commission of experts. They met in the Spanish cities of Salamanca and Córdoba during 1486 and 1487 under the leadership of Isabella’s spiritual adviser, Hernando de Talavera. Although the committee’s first report rejected Columbus’s plan, Isabella granted him a small salary to keep him at the royal court. During this period, Columbus lived with a woman named Beatriz Enríquez de Harana. She gave birth to his second son, Ferdinand, in 1488.

For the next several years, Columbus followed the Spanish court as it traveled through the country. In 1490, the experts issued a final report. They scoffed at his plan—not because they thought that the world was flat or sea monsters would devour the ships, but because they still believed his estimates were wrong. The committee favored the belief that the world was large and covered mostly by water rather than small and composed mostly of land. In addition, Columbus’s demands had increased. He wanted to become a titled aristocrat, to rule the lands he discovered, and to be able to pass these privileges on to his sons. Columbus also wanted to be given a percentage of the wealth he brought back to Spain.

Success in Spain.

Columbus refused to give up. He sent his brother Bartholomew to seek support from the English and French courts, but the attempts were unsuccessful. Columbus’s chance finally came when Spain defeated Granada in January 1492. In the aftermath of this victory, Luis de Santangel, a secretary in charge of Isabella’s household expenses, played a decisive role in convincing the queen that she was missing a great opportunity. Thus, in April 1492, Columbus’s plan suddenly received royal approval. There is no truth to the story that Isabella offered to pawn her jewels to pay for the voyage. Santangel advanced the funds for the relatively low costs of the expedition.

First voyage westward

Ships and crews.

Palos, a small port in southwestern Spain, was home to the Pinzon and Nino families. In payment of a fine they owed the monarchy, they provided two of the ships and selected the crews for Columbus’s first voyage. Martín Alonso Pinzón, an experienced seafarer, captained the Pinta, a caravel with square-rigged sails that could carry about 53 long tons. A long ton is equal to 2,240 pounds or 1.016 metric tons. His brother Vicente Yañez Pinzón captained the slightly smaller Niña. Columbus captained the third vessel, the Santa María. It was chartered from Juan de la Cosa, who came along as sailing master. It was slightly bigger than the other two ships but provided few comforts.

A total of about 90 crew members sailed aboard the three ships. In addition to the officers and sailors, the expedition included a translator, three physicians, servants for each captain, a secretary, and an accountant.

Aboard ship, there was endless work to be done handling the sails and ropes and pumping out water that seeped or washed aboard. Cleaning and repair work filled the remaining hours. The crews cooked on portable wood-burning stoves. Their main meal consisted of a stew of salted meat or fish, hard biscuits, and watered wine. The sailors had no sleeping quarters, so they huddled on deck in good weather or found a spot below deck during storms. Only a few of the officers had bunks.

Sailing west.

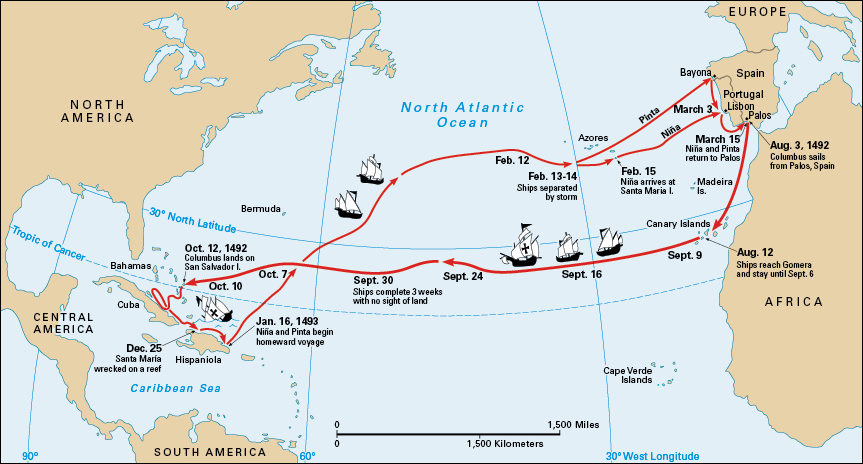

The fleet set out from Palos on Aug. 3, 1492, and sailed to the Canary Islands, a Spanish possession off Africa’s coast. Repairs were made on the island of Gran Canaria, and the crews loaded provisions on the island of Gomera. The ships left Gomera on September 6. Columbus journeyed south before sailing west in order to take advantage of the trade winds. At that latitude, these winds always blow from the northeast.

Columbus had few navigational instruments. He knew enough about celestial navigation to measure latitude by using the North Star. However, he had no instruments for determining the ship’s position from the stars except a crude quadrant that was not accurate when the ship rolled. He used a compass to plot his course, estimated distances on a chart, relied on a half-hour glass to measure time, and guessed his speed. Together, these activities make up a method of navigation known as dead reckoning.

After a month of smooth sailing, the crews became anxious that they had not yet reached the islands Columbus had led them to expect. They had not sighted land for longer than any other crew of that time. Only the authority of the Pinzón brothers enabled Columbus to quiet the crews’ loudly expressed doubts. Then, signs of approaching land began to appear, such as coastal seaweed on the surface of the water and land-based birds flying overhead.

Between the evening of October 11 and the morning of October 12, a sailor on the Pinta named Juan Rodríguez Bermejo called out, “Land, land!” Isabella had offered a reward to the first person to sight land. However, Columbus said that he had seen a flickering light hours earlier, and he claimed the reward.

The first landing.

Before noon on October 12, the ships landed on an island in the Caribbean Sea. Columbus named the island San Salvador (Spanish for Holy Savior). He later learned that inhabitants of the area called the island Guanahani. However, historians are not sure which island this is. In 1926, Watling Island in the Bahamas was officially renamed San Salvador Island because Columbus scholars considered it the most likely landing site. Other islands where he might have landed include Samana Cay and Conception in the Bahamas, and Grand Turk in the Turks Islands.

Columbus believed he had arrived at an island of the East Indies, near Japan or China. Because of this belief, he called the islanders Indians. People realized within a few years that Columbus had not reached the Indies, but the name Indian continued to be used.

The islanders were probably the Taíno, a subgroup of the Arawak people. They were skilled farmers who made cotton cloth, grouped their dwellings into villages, and had well-developed social and governmental systems. Columbus described them as gentle, “primitive” natives living in an island paradise. However, his attitude toward them held contradictions. The islanders’ apparent innocence and simplicity made them seem like ideal candidates for conversion to Christianity. But these qualities also made them targets for mistreatment, and Columbus did not hesitate in kidnapping several islanders to present to his patrons in Spain. Columbus’s conflicting feelings about the Native Americans would be echoed throughout the development of Spain’s American empire.

On October 28, the fleet entered the Bay of Bariay off Cuba. Thinking they were near the Asian mainland, the captains explored harbor after harbor. They then sailed along the northern coast of the island of Hispaniola, now divided between the Dominican Republic and Haiti. Columbus called it La Isla Española (the Spanish Island).

The night of December 24, an exhausted Columbus gave the wheel of the Santa María to a sailor, who passed it to a cabin boy. The ship crashed and split apart on a reef near Cap-Haïtien, in present-day Haiti. Aided by a local chief, the crew built a makeshift fort. Columbus left about 40 men there to hunt for gold. He then started home on the Niña, sailing from Samana Bay on the northeast coast of Hispaniola on Jan. 16, 1493. He brought several captured Taíno with him. Martín Pinzón captained the Pinta.

Return to Spain.

The homeward voyage was rough and difficult. Some of the Taíno died. After about a month of travel, the Niña and the Pinta became separated during a storm. The Niña came ashore on the Portuguese island of Santa Maria in the Azores. Columbus and his crew were almost arrested by the governor, who assumed they had been trading illegally in Africa. Columbus was permitted to set out again, but storms forced him to seek shelter in Lisbon. The Niña finally reached Palos on March 15, 1493.

Columbus had been concerned that Martín Pinzón, with whom he had quarreled at times, would reach Spain first and claim the glory. Indeed, Pinzón had reached a small village in Spain a few days earlier and had notified the monarchs of his arrival. However, they refused to see him until they had heard from Columbus, and Pinzón died before he could tell his story. The Pinta arrived at Palos a few hours after the Niña.

Columbus reported to Ferdinand and Isabella at Barcelona, Spain, where they gave him a grand reception. Columbus had little to show except some gold trinkets, parrots, and a few Taíno, but the monarchs determined to exploit his find. They quickly asked Pope Alexander VI to recognize their control over Columbus’s current and future discoveries. The pope granted Ferdinand and Isabella the right to preach the Christian faith in the islands, and they used this right as the basis for sweeping claims over the lands. To avoid conflicts, the pope also established a Line of Demarcation. He gave Spain the right to explore and to claim new lands west of the line and gave Portugal the same rights east of the line. However, Portugal complained that these terms violated an earlier treaty and that the line was too close to its discoveries.

In 1494, negotiations opened in the town of Tordesillas in Spain. Spain and Portugal eventually agreed to move the imaginary line farther west. At the time, they thought their new line was about midway between Portugal’s claims on the Cape Verde Islands and Columbus’s new discoveries. This treaty set the foundation for Spanish land claims in the Americas and later enabled Portugal to claim Brazil and the Newfoundland Banks. See Line of Demarcation.

Second voyage westward

Return to the islands.

Columbus’s first expedition caused such excitement that he was put in charge of 17 ships for a second voyage. The crew of about 1,200 to 1,500 men included colonists and private investors who intended to settle on the islands. Most dreamed of quick wealth and a rapid return home. Friars went along to try to convert the “Indians” to Christianity.

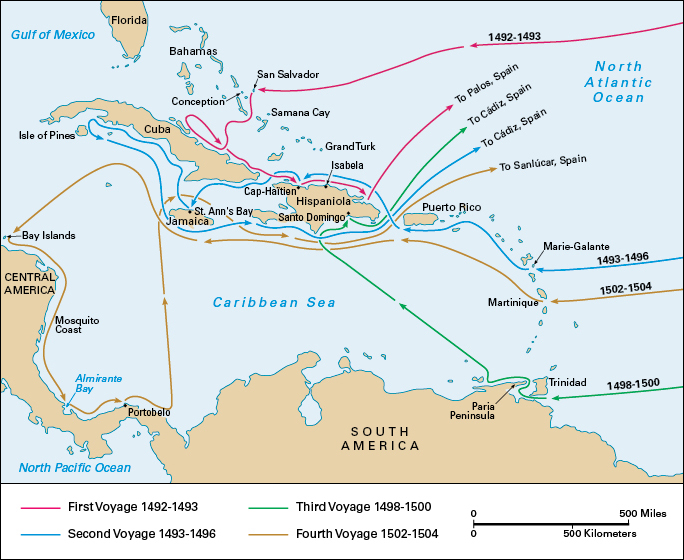

The fleet sailed from Cádiz, Spain, on Sept. 25, 1493. It took on supplies in the Canaries and completed the ocean crossing in a speedy 21 days. In another three weeks, the ships reached Hispaniola. They passed many islands. Columbus named one of them—present-day Marie-Galante in the eastern Caribbean—after his flagship. Columbus also landed briefly at Puerto Rico.

Trouble, settlement, and exploration.

In Hispaniola, Columbus searched in vain for the sailors he had left at the fort. No one discovered exactly what had happened, but apparently the crew had fought among themselves, possibly over local women. The survivors probably had been killed by the Taíno, whom they had mistreated.

Columbus moved eastward along the north coast of Hispaniola and established Isabela and other fortified posts. The Spanish colonists quickly saw that the riches promised by Columbus would not materialize. They resented being given orders by a Genoan rather than a Spaniard, and some fell ill from tropical fevers. Shortly after their arrival, 12 of the 17 ships returned to Spain with orders to bring more supplies to Isabela. The ships also carried discontented colonists back to Spain. To prevent rebellion, and also to make the voyage produce a quick profit to impress his backers, Columbus sent some men into Hispaniola’s interior to search for gold.

Leaving his brother Diego in charge, Columbus left Isabela in the spring of 1494 to explore the southern coast of Cuba (which he called Juana). After traveling down the island’s long coastline, Columbus declared that it was the Asian mainland. Although this was not so, he forced the crews to sign an affidavit saying they agreed with him. Columbus did this because it was crucial to his contract with the Spanish monarchs to have discovered Asia. Otherwise, they could deny him the desired titles for which he had negotiated. Columbus also landed at Jamaica.

When Columbus returned to Hispaniola, he found his brothers Bartholomew and Diego waiting for him. Columbus immediately appointed Bartholomew provincial governor of Hispaniola. This appointment angered many of the Spanish settlers. In addition, they complained about having only cassava (tapioca), corn, fish, and yams to eat.

The brothers also sought to punish the Taíno, who were no longer peaceful after the Europeans had treated them harshly. In addition, the Taíno had begun to suffer and die from infectious diseases brought over unintentionally by the Europeans, and food had become scarce. Such was his need for profits that Columbus tried to force all the male Taíno over age 14 to pan rivers for gold. Those who failed to collect an assigned quota of gold were punished, sometimes by having their hands cut off. But the quotas could not be met. When the Indians threatened to rebel, Columbus used their rebellion to justify attacking them.

In Spain, the friars and Spanish colonists who had left Hispaniola in early 1494 complained to Ferdinand and Isabella about conditions on the island. The priests criticized the maltreatment of the Taíno, and the colonists charged Columbus with misgovernment in the colony. Columbus decided to return to Spain to defend himself, arriving in June 1496. Again, Columbus’s powerful oratory and impressive presence succeeded. The king and queen reconfirmed his titles and privileges, and they granted his request for additional men, supplies, and ships. But few men wanted to sail with him this time because the islands had failed to yield the expected profit. To assemble crews, Ferdinand and Isabella had to pardon prisoners. So low had Columbus’s reputation sunk that his sons, who served as pages at court, were mocked by other boys. They jeered, “There go the sons of the Admiral of the Mosquitoes.”

Third voyage westward

Third journey to the west.

On May 30, 1498, Columbus departed from Sanlúcar, Spain, with six ships. He charted a southerly course. Ferdinand and Isabella wanted Columbus to investigate the possibility that the Asian mainland lay south or southwest of the lands he had already explored. The possibility that such a mainland existed had been accepted by the king of Portugal, and Spain wanted to stake its claim.

The fleet ran into a windless region of the ocean and was becalmed in intense heat for eight days. It reached an island Columbus called Trinidad (meaning Trinity) on July 31 and then crossed the Gulf of Paria to the coast of Venezuela. Columbus observed an enormous outflow of fresh water—later found to come from the Orinoco River—that made him realize this land could not be an island. He wrote in his journal: “I believe that this is a very great continent which until today has been unknown.” Columbus considered that the great rush of fresh water must be a river flowing from the Garden of Eden.

Some scholars believe that while in Spain, Columbus had heard of an English-sponsored landing in 1497 along North America’s northeastern coast by the Italian explorer John Cabot. The news may have made Columbus doubt whether he himself really had reached Asia. Columbus did not mention his doubts, preferring first to explore and claim the area where he had landed for Spain. Columbus’s failure to acknowledge that he had landed on a new continent had the effect that instead of being named for Columbus, America came to be named after Amerigo Vespucci, a later Italian navigator. A few years later, a document backdated to 1497 erroneously claimed that Vespucci had been the first to explore the mainland of a “New World.”

Problems in Hispaniola.

Columbus found the Hispaniola colony seething with discontent. He tried to quiet the settlers by giving them land and letting them enslave the Taíno to work it, but that failed to satisfy many. Francisco Roldán, the chief justice, had led a rebellion. For a time, Roldán and the Taíno—with whom he had established an alliance—held part of the island. Columbus managed to subdue the rebellion through negotiation and a show of force.

Columbus in disgrace.

By 1500, many complaints about Columbus had reached the Spanish court. Ferdinand and Isabella sent a commissioner named Francisco de Bobadilla to investigate. Upon arrival in Santo Domingo—the capital of Hispaniola—in August 1500, Bobadilla was shocked by the sight of several Spanish rebels swinging from gallows. He freed the remaining prisoners, arrested Columbus and his brothers, put them in chains, and sent them to Spain for trial. Once at sea, the captain of Columbus’s ship offered to unchain him. But Columbus refused, saying he would only allow the chains to be removed by royal command.

In Spain, Columbus and his brothers were released by order of the king and queen. The rulers forgave Columbus, but with conditions. Columbus was allowed to keep his titles, but he would no longer be permitted to govern Hispaniola. The king and queen sent Nicolás de Ovando, with about 30 ships carrying 2,500 colonists, to govern the island.

Fourth voyage westward

The final voyage.

Columbus planned still another journey, which he called the “High Voyage.” He saw it as his last chance to fulfill the promise of his earlier expeditions. His goal was to find a passage to the mainland of Asia. Columbus still believed that China lay close by. Ferdinand and Isabella granted his request for ships because they, too, believed he had come close to his goal and they did not want to lose his services to another country. But they instructed him not to stop at Hispaniola unless absolutely necessary to get supplies, and then only in preparation for his return to Spain.

On May 9, 1502, Columbus set sail from Cádiz, Spain, with four ships. Columbus’s son Ferdinand, about 14 years old, sailed with his father. Ferdinand’s account of the trip, though written many years later, remains the best record of the voyage. The fleet stopped briefly at the Canary Islands, then sailed to Martinique in the eastern Caribbean in just 21 days. It then headed toward Hispaniola.

A dangerous hurricane.

Governor Ovando was sending 21 ships to Spain when he received a message from Columbus warning of an impending storm and asking permission to land. Feeling contempt for Columbus, and reminding him that he was forbidden to land at Hispaniola, Ovando ignored the warning and sent his ships to sea. Columbus’s fleet weathered the storm. However, all but one of Ovando’s ships sank in a hurricane. Columbus’s enemies Bobadilla and Roldán drowned. Amazingly, the ship that reached Spain was the one carrying Columbus’s share of the gold collected in Hispaniola, and the personal possessions he had left there.

Further explorations.

At the end of July, Columbus and his fleet reached the coast of Honduras. For the rest of the year, they sailed east and south along the coasts of what are now Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and Panama. The ships were battered by rough winds and driving rains, and the voyage demonstrated Columbus’s considerable navigational skill.

At the narrowest part of the Isthmus of Panama, Columbus heard tales that a large body of water lay a few days’ march across the mountains. But he did not follow up on this information, so he missed a chance to become the first European to see the Pacific Ocean. He also narrowly missed establishing contact with the rich, advanced Maya culture. Columbus abandoned his search for a passage to Asia on April 16, 1503. He was exhausted and probably suffering from malaria, which made him delirious.

The hard journey home.

Columbus’s fleet had to move slowly, because his ships were leaking badly from holes eaten in the planking by shellfish. On June 25, the two remaining ships had to be beached at St. Ann’s Bay, which Columbus had called Santa Gloria, on the northern coast of Jamaica.

Columbus realized that the chances were slim of another expedition arriving to rescue him and his crew. Captain Diego Mendez paddled to Hispaniola in a dugout canoe for help, but Governor Ovando refused to provide a ship until more vessels arrived from Spain.

The crews had no tools to repair the ships or to build new ones, and they made no effort to feed themselves. Instead, they relied on the islanders to provide food. The Jamaicans started avoiding them. Columbus later claimed that he used information from an almanac to predict a total eclipse of the moon, which so impressed the islanders that they resumed providing food.

At last, at the end of June in 1504—after being marooned for a year—Columbus and the 100 surviving crew members sailed from Jamaica on a ship chartered by Mendez. They reached Sanlúcar, Spain, on Nov. 7, 1504.

Final days

Queen Isabella died just a few weeks after Columbus returned to Spain. King Ferdinand granted Columbus an audience and listened to his requests. Ferdinand tried to persuade Columbus to trade in the rewards and privileges due him in exchange for an estate in north-central Spain. Columbus, in turn, tried to persuade Ferdinand to restore his authority and increase his income, but these requests were not granted.

Columbus spent his last days in a modest house in Valladolid, Spain, suffering from a disease that may have been Reiter’s syndrome, a form of joint inflammation. On May 20, 1506, Columbus died. Many people believed Columbus was poor at the time of his death, but he actually died wealthy.

Columbus’s remains were transported to Seville, Spain, and later to Santo Domingo, in what is now the Dominican Republic. Some people believe that his bones were moved to Havana, Cuba, in 1795, and, finally, back to Seville in 1899. Others believe that the bones of one of Columbus’s brothers or of his son Diego were removed from Santo Domingo instead. In 2006, Spanish researchers found DNA evidence that at least some of Columbus’s remains are in Seville.

Columbus’s impact on history

Christopher Columbus had a strong will and stuck with his beliefs. His single-minded search for a westward route to Asia unintentionally changed Europeans’ commonly accepted views of the world and led to the establishment of contact between Europe and the Americas.

Many exchanges took place between the Eastern and Western hemispheres as a result of Columbus’s voyages. The Europeans grew important cash crops—cotton, rubber, and sugar cane—in the Americas. They established vast plantations worked by Native Americans and by imported African slaves. They also obtained such precious metals as gold and silver in vast quantities. These valuable resources created fortunes for the Dutch, English, French, Portuguese, Russians, and Spanish. The wealth and human resources of the Western Hemisphere gave these countries a huge advantage over the rest of the world in later centuries.

The Americas also provided many foods that became popular throughout the world, including maize (corn), cassava, cayenne, chocolate, hot peppers, peanuts, potatoes, and tomatoes. Europe and Asia, in exchange, supplied the Americas with cattle, goats, honey bees, horses, pigs, rice, sheep, and wheat, as well as many trees and various other plants. This agricultural exchange revolutionized the economies and styles of cooking of both hemispheres.

Europeans unintentionally brought many deadly diseases to America. The previous separation of the Native American peoples from those of Europe and Asia meant that the Native Americans had no natural immunity to these diseases. As a result, measles, smallpox, typhus, and other infectious diseases swept through the newly exposed populations, killing vast numbers of people. In turn, some Europeans became infected by a form of syphilis unknown in Europe.

Research in the late 1900’s and early 2000’s into the life and times of Christopher Columbus has somewhat diminished his heroic image as an isolated visionary by placing him in the context of a broad wave of exploration. Historians continue to praise his persistence, courage, and maritime ability. Critics point to his cruelty to the Native Americans, his poor administration of Hispaniola, and his role in beginning the heedless exploitation of the natural resources of the Americas. Nevertheless, Columbus’s explorations ended centuries of mutual ignorance about what lay on either side of the Atlantic Ocean. To him belong both the glory of the encounter and a share of the blame for what followed.