Compound eye is a type of eye that has many tiny lenses close together. Compound eyes differ from eyes that have only one lens, such as those of fish, birds, and mammals, including human beings. Two large groups of animals have compound eyes–insects and crustaceans, which include crabs and lobsters.

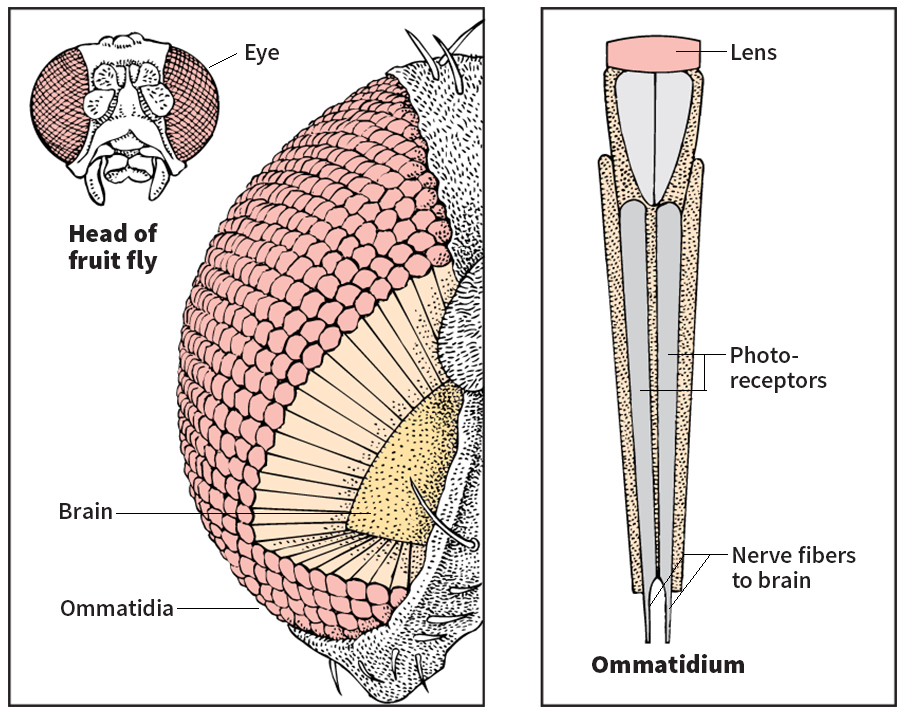

The number of lenses in a compound eye varies from fewer than 100 to more than 20,000 among different species of animals. Each lens is the top part of a structure called an ommatidium. Beneath the lens, an ommatidium consists of many light-sensitive cells called photoreceptors, each of which is connected to the brain by a nerve.

The surface of a compound eye is curved. As a result, no two ommatidia face exactly the same direction. Each ommatidium registers an impression of a small part of the animal’s surroundings. A single ommatidium does not produce clear images of objects. Instead, the impressions from all the ommatidia form a “mosaic,” from which the animal’s brain distinguishes patterns of light and color. A compound eye has no mechanism for focusing, and so only nearby objects can be seen sharply. However, a compound eye is ideal for detecting motion because even the slightest movement causes a different image to fall on each ommatidium.

Many species of insects have compound eyes that can see ultraviolet light as a distinct color. The human eye cannot do this. Similarly, certain insects can detect the plane of polarization in polarized light, an ability that the human eye lacks (see Polarized light). The ability to detect the plane of polarization helps such insects as ants and bees to navigate by using the sun, because the polarization of sunlight varies according to the sun’s position in the sky.