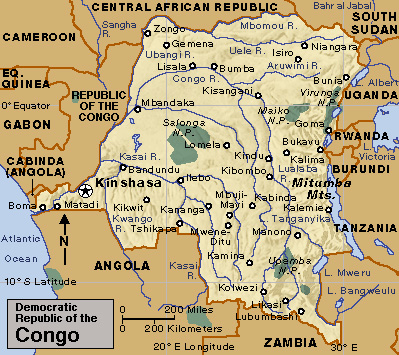

Congo, Democratic Republic of the (DRC) is a large country in the heart of Africa. A narrow strip of Congo borders the Atlantic Ocean. But most of the country lies deep in the interior of Africa, slightly south of the center of the continent. The equator runs through the northern part of the country.

One of the world’s largest and thickest tropical rain forests covers about a third of the DRC. The mighty Congo River flows through the forest and is one of the country’s chief means of transportation. Many kinds of wild animals live in the country.

Over half of Congo’s people are farmers and live in small rural villages. But each year, many villagers move to the cities. Kinshasa is the country’s capital and largest city.

Belgians ruled what is now the DRC from 1885 until it became the independent nation of Congo in 1960. The nation was known as Zaire from 1971 to 1997. Rebels seized power in 1997 and named it the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The country is sometimes called Congo (Kinshasa) to distinguish it from the neighboring Republic of the Congo, or Congo (Brazzaville). The DRC’s full name in French, the official language, is République Démocratique du Congo.

Europeans greatly influenced Congo’s economic and cultural life up to the time of independence. Congo’s people are divided into a large number of different ethnic groups. Civil wars and severe economic problems have hindered the country’s development.

Government

National government.

The president is elected to a five-year term and can serve two terms. The president names the prime minister from the party elected to the most seats in Parliament. Parliament consists of a 500-member National Assembly and a 108-member Senate. Assembly members are elected by the people, and Senate members are elected by provincial parliaments. Both Assembly and Senate members serve five-year terms.

Local government.

The country has 25 provinces plus the separate city of Kinshasa. Each province has a parliament, and a governor elected by the parliament.

Courts.

The country’s Constitutional Court handles constitutional issues. The Court of Cassation has jurisdiction over judicial cases, and the Council of State hears administrative cases. Congo also has a High Military Court.

Armed forces

of the DRC include a land army and a small air force and navy. Military service is voluntary.

People

Ancestry.

Most of Congo’s people are descendants of people who began moving to the area from other parts of Africa at least 2,000 years ago. At that time, other African peoples, including a Pygmy group called the Mbuti, lived in what is now the DRC. The Mbuti, like other Pygmy groups, are known for their small size. Today, Congo’s people belong to many different ethnic groups. At times, conflicts between the ethnic groups have flared up over control of political power and natural resources. At other times, the groups have had peaceful relations.

Languages.

Most of Congo’s ethnic groups have their own local language. About 200 local languages are spoken in the country. Most of these local languages are Bantu languages that are closely related (see Bantu ).

Most Congolese also speak at least one of the country’s four national languages—Kikongo, Lingala, Swahili (also known as Kiswahili), and Tshiluba. French is Congo’s official language. Government officials often use French in their work, and many of the country’s students learn it in school.

Way of life.

Most rural Congolese live in small villages that range in size from a few dozen to a few hundred people. The vast majority of village families farm a small plot of land. They raise almost all their own food, including cassava, corn, and rice. Some rural people also catch fish. Few families in the countryside can afford farm machinery, and so most use hand tools. As a result, farm production is low, and most farm families are poor.

After 1960, large numbers of Congolese—especially young people—moved from rural areas to cities. These people were attracted to the cities by the opportunity for jobs in business, industry, and government. The rapid growth of the cities has led to such problems as unemployment and crowded living conditions. In addition, many of the people who have jobs earn low wages and find it difficult to support themselves and their families.

During Belgian rule, few Congolese women received more than a few years of education or held a job outside the home. After independence, the government increased educational and job opportunities for women.

Housing.

Most rural Congolese live in houses made from mud bricks or dried mud and sticks. The majority of the houses have thatched roofs. The houses of some well-to-do rural families have metal roofs.

In Congo’s cities, business managers and merchants—as well as many Europeans—live in attractive bungalows. But many factory and office workers live in crowded areas of small, cheap houses and apartments made from cinder blocks or mortar bricks.

Clothing.

After independence, most Congolese men who held important jobs adopted a kind of national costume. They wore trousers with a matching collarless jacket that buttoned at the neck. No shirt or tie was worn with this costume. Most male workers and farmers wear long or short trousers with a shirt. Congolese women usually wear a long, one-piece dress of cotton cloth or a blouse and long skirt.

Food and drink.

Corn, rice, and manioc meal—which is made from cassava—are the basic foods of most of the people. Congolese serve these foods mostly as a thick porridge flavored with a spicy sauce. They add fish or meat to the porridge when they can afford to do so. Beer is a popular beverage. The diet of many Congolese lacks important nutrients, especially protein. As a result, many Congolese suffer from malnutrition.

Recreation.

Rural Congolese enjoy social gatherings that feature drum music and dancing. Many city people spend much leisure time in barrooms. There, they dance and listen to Congolese jazz provided by recordings or small bands. Soccer ranks as the country’s most popular spectator sport.

Religion.

Most Congolese are Christians. Roman Catholics make up the largest Christian group in the country, followed by Protestants and Kimbanguists. Kimbanguists are members of an independent Christian church called the Church of Jesus Christ on Earth. Other Congolese are Muslims (followers of Islam) or practice local African religions.

Education.

Children from 6 to 12 years old are required to attend school. But many areas lack enough schools, and this requirement is not strictly enforced. Most parents value education as a key to a better life for their children. Enrollment at elementary schools and secondary schools rose after independence. A secondary school student must pass a nationwide examination to receive a diploma. Schools in remote rural areas are poorly equipped compared with those in other parts of Congo. Many students from the rural areas fail the diploma exam.

Congo has a number of universities, including major universities at Kinshasa, Kisangani, and Lubumbashi.

The arts.

Carved wooden statues and masks by Congolese artists have been praised by art critics for their delicate form and balance and rich symbolism. Music is also a major art in Congo. The rhythm of drums dominates Congolese music. Since the 1950’s, urban Congolese have developed their own form of jazz, which blends elements of modern jazz and traditional Congolese music.

Loading the player...Folk music from the Democratic Republic of the Congo

Land and climate

The DRC ranks second in area among the countries of Africa. Only Algeria is larger than Congo. The country’s land includes three distinct kinds of regions: (1) a tropical rain forest, (2) savannas, and (3) a highland.

The tropical rain forest

covers most of the northern part of Congo. It is one of the world’s largest and thickest rain forests and has an extraordinary variety of trees and other plants. The forest is so thick that sunlight seldom reaches parts of its floor.

The equator runs through the rain forest, and the area has hot, humid weather all year. Daytime temperatures average about 90 °F (32 °C). Annual rainfall often totals 80 inches (203 centimeters) or more. Much of it falls in heavy thunderstorms.

Savannas.

A savanna covers much of southern Congo. Another savanna covers a strip of land north of the rain forest. The savannas are chiefly grasslands, and a variety of grasses grow there. Small groups of trees are scattered throughout the savannas, and forests grow in some valleys. Daytime temperatures in the savannas average about 75 °F (24 °C). The savannas receive little or no rain for several months each year. Annual rainfall averages about 37 inches (94 centimeters).

The highland

is an area of plateaus and mountains along the country’s eastern and southeastern borders. Plant life varies with the elevation. Margherita Peak, the highest point in Congo, rises 16,762 feet (5,109 meters) there. Daytime temperatures average about 70 °F (21 °C). Annual rainfall totals about 48 inches (122 centimeters).

Rivers and lakes.

The Congo River is the DRC’s most important waterway. It rises near the southeast corner of the country. The river flows northward to northern Congo and is called the Lualaba River until it reaches Boyoma Falls near the equator. It then flows westward across northern Congo. Finally, it flows southwestward until it empties into the Atlantic Ocean in far western Congo. The Congo River is the world’s fifth longest river. It flows for 2,900 miles (4,667 kilometers). The Congo carries more water than any other river except the Amazon. Many other rivers branch out from the Congo. They include the Ubangi and Aruwimi to the north and the Lomami and Kasai to the south.

Several deep lakes lie along Congo’s eastern border. The largest is Lake Tanganyika.

Animal life.

The DRC has a spectacular variety of wild animals. Baboons, chimpanzees, gorillas, and many kinds of monkeys live in areas with trees. Antelope, leopards, lions, rhinoceroses, and zebras roam open areas. Crocodiles live in swamps and on river banks. The okapi, a forest-dwelling animal related to the giraffe, lives nowhere else in the world but Congo. It has become a national symbol of the country. Through the years, European hunters killed many animals in Congo and endangered some species. The government set aside large areas of land as part of a national park system where animals are protected from hunters. Many wild animals also still live outside the parks, especially in thinly populated areas in eastern Congo.

Economy

The DRC is a poor country with a developing economy. But it has many valuable resources that give it the potential of becoming a wealthy nation. Agriculture and mining rank among Congo’s most important economic activities.

Agriculture and forestry.

Agriculture in Congo centers around small plots, where families struggle to produce enough food for their own needs. The chief food crops include bananas, cassava, corn, plantains, and rice. Crops raised for sale include cocoa, coffee, cotton, and tea. The trees of Congo’s rain forest yield palm oil, rubber, and timber. Farmers in Congo also raise cattle, chickens, goats, and sheep.

Mining.

Cobalt, copper, diamonds, and petroleum are among the country’s most important minerals. Congo produces more cobalt than any other country. A huge copper mine operates in the southeastern part of the country. Congo is a world leader in the production of diamonds. Congo produces petroleum from deposits off its coast and the eastern part of the country. Other economically valuable minerals include coltan, gold, silver, tin, and zinc. Coltan is a mineral used in cellular phones, laptop computers, and other electronic devices.

Manufacturing.

The DRC produces relatively small amounts of manufactured goods. Its products include cement, processed foods and beverages, and textiles. After independence, manufacturing grew in importance in Congo.

Foreign trade.

Cobalt and copper are important exports. Other exports include coffee, diamonds, petroleum, and wood products. Imports include food, machinery, petroleum, and transportation equipment. Congo trades with Belgium, China, South Africa, and Zambia.

Transportation and communication.

Most roads in the DRC are unpaved, and many are badly rutted, particularly in rainy seasons. Few Congolese own an automobile. The Congo River plays an important role in Congo’s transportation system, especially in the rain forest where there are few good roads. The river and its many branches are navigable for about 7,200 miles (11,500 kilometers) in the country. Congo’s railroads operate mostly in the southeastern part of the country. They link mining areas there with river ports and seaports. Matadi is the country’s chief seaport. Goma, Kinshasa, and Lubumbashi have international airports.

Radio is the chief means of communication in Congo. State-owned and private television stations broadcast throughout much of the country. A number of daily newspapers are published in Congo.

History

Early days.

The Mbuti were the first known inhabitants of what is now the DRC. They have lived there since prehistoric times. At least 2,000 years ago, people from other parts of Africa moved into the area. In the A.D. 700’s, well-developed civilizations emerged in southeastern Congo. In the 1400’s—or perhaps earlier—several separate states developed in the savanna south of the rain forest. The largest were the Kongo, Kuba, Luba, and Lunda kingdoms. In the 1600’s or 1700’s, other kingdoms grew up near the eastern border. They carried on long-distance trade with people on the east and west coasts.

The coming of the Europeans.

In 1482, Portuguese sailors began stopping at the mouth of the Congo River. Portugal soon established diplomatic relations with the Kongo kingdom, which then ruled the coastal region. Representatives of the kingdom visited Portugal and the Vatican—the headquarters of the Roman Catholic Church—in the late 1400’s. The Kongo king and some members of the nobility soon adopted Roman Catholicism as their religion. A number of Kongo men became Catholic priests, and the pope appointed one of them as a bishop.

In the early 1500’s, the Portuguese began enslaving Africans. They bought many of the slaves from the leaders of the Kongo kingdom. Other Europeans soon began taking part in the slave trade. From the early 1500’s to the early 1800’s, hundreds of thousands of people were enslaved in the Congo area. Most of them were sent to South America or the Caribbean.

In 1876, Henry M. Stanley, a British explorer, crossed Congo from east to west. Other explorers crossed the area at about the same time. The explorations gave Europeans and Americans their first detailed information about the interior of what is now the DRC.

Belgian rule.

In 1878, King Leopold II of Belgium hired Stanley to set up Belgian outposts along the Congo River. Through skillful diplomacy, Leopold persuaded other European leaders to recognize him as the ruler of what is now the DRC. The recognition stated that Leopold himself—not the Belgian government—was the ruler. The area became Leopold’s personal colony on July 1, 1885, and was named the Congo Free State.

The people of the Congo Free State suffered under Leopold’s rule. The king’s agents treated the people cruelly. For example, they forced villagers to collect a specified amount of rubber in the wild. If the villagers failed to do so, their hands, fingers, or feet were amputated. Women and children were held hostage until their male relatives could provide the required amount of rubber. Leopold’s agents also burned villages and farms. Millions of Congolese died as a result of the harsh treatment.

Leopold’s rule brought many protests, especially from the United Kingdom and the United States. In response, the Belgian government took over control of the Congo Free State from Leopold in 1908. Belgium renamed the colony the Belgian Congo. The Belgian government’s rule was often harsh, but the government improved working and living conditions somewhat.

By the 1920’s, Belgium was earning great wealth from the Belgian Congo’s copper, diamonds, gold, palm oil, and other resources. The worldwide Great Depression of the 1930’s crippled the colony’s economy as prices and demand for its resources fell sharply. In 1940, Belgium entered World War II on the side of the Allies. During the war, the Belgian Congo provided the Allies with valuable raw materials.

After World War II ended in 1945, the Belgian Congo’s economy again developed rapidly as prices for its exports soared. The Belgians made efforts to improve education and medical care for the colony’s people. But they refused to give them a voice in the government.

Independence.

In the 1950’s, many Africans in the Belgian Congo began calling for independence from Belgium. In 1957, Belgium allowed the colony’s people to elect their own representatives to some city councils. But the demand for independence continued. In 1959, rioting broke out against Belgian rule. On June 30, 1960, Belgium granted the colony independence. The new country was called Congo.

In Congo’s first general elections—held about a month before independence—nine political parties won seats in the national legislature. No party received an overall majority. This splitting of votes weakened the power and unity of Congo’s government. In a compromise on the eve of independence, two opposing leaders agreed to share power. Joseph Kasavubu became president, and Patrice Lumumba became prime minister.

Civil disorder

broke out in Congo following independence. Belgian officers still held power in the army, and many Belgians retained important government posts. Five days after independence, Congolese army troops near Leopoldville (now Kinshasa) revolted against their Belgian officers. The revolt spread throughout Congo. Most Belgian government officials then fled the country.

In July 1960, Katanga Province seceded (withdrew) from the new nation and declared itself independent. This copper-producing province in the south ranked as Congo’s wealthiest area. The diamond-producing province of Kasai seceded in August. Other provinces threatened to secede, and Congo’s government weakened. In July, United Nations (UN) troops—at the invitation of the government—were sent to Congo to restore order. In September, Colonel Joseph Désiré Mobutu led a military coup and ousted Prime Minister Lumumba. Lumumba was imprisoned, and in 1961, he was assassinated. In August 1961, the rival groups reached a compromise that united all of the country except Katanga Province. Cyrille Adoula headed the new government as prime minister.

United Nations troops finally brought an end to the Katanga secession in 1963. Some of the Katanga rebels fled to neighboring Angola. The UN forces were withdrawn in June 1964. In a surprising political settlement in July, Moise Tshombe, who had led the Katanga secession movement, became prime minister of the reunited country. At about the same time, a wave of new revolts broke out in Congo. White mercenaries (hired soldiers) helped the government end the revolts by 1965.

National elections were held in March 1965. A loose coalition headed by Tshombe won the elections. But the coalition soon fell apart. In November, the Congolese army took control of the government. Mobutu became president.

Rebuilding the nation.

The civil disorder of the early 1960’s severely damaged Congo’s economy. Fighting among the country’s people resulted in bitterness and deep divisions. President Mobutu took steps to try to solve Congo’s problems. He set up a strong national government that extended its authority in Congo. His party, the MPR, became the country’s only political party. The government’s authority helped end the revolts by Lumumba supporters. It also helped lessen the ethnic divisions of earlier years.

Mobutu also tried to strengthen the nation by encouraging pride in its African heritage and reducing European influence. Many cities, towns, and physical features in the country had European names. Mobutu’s government gave them African names. In 1971, the government changed the country’s name from Congo to Zaire. The government also required all Africans in the country who had European names to adopt African ones. Mobutu changed his own name from Joseph Désiré Mobutu to Mobutu Sese Seko in 1972.

The 1970’s.

In the early 1970’s, the worldwide problems of recession and inflation caused new economic hardships in Zaire. The price of copper fell sharply, greatly reducing the country’s revenues. At the same time, the prices of food and oil—which the country imports—rose dramatically.

In 1977, Katanga rebels who had been living in Angola invaded Zaire in an attempt to overthrow Mobutu. Zairian government troops, aided by Moroccan troops and French military equipment, defeated the rebels. Katanga rebels invaded Zaire again in 1978 but were defeated. French and Belgian troops helped the Zairian forces turn back the invasion.

The fall of Mobutu.

During the 1980’s, severe economic problems and a lack of political freedom resulted in growing public dissatisfaction in Zaire. The standard of living for most Zairians grew worse, and many government services deteriorated. In 1990, public pressure led Mobutu to permit the formation of opposition political parties. In 1991, looting by mutinous soldiers and rioting by civilians forced Mobutu to agree to give up the monopoly on power he had held since 1965. He agreed to share control with a prime minister and a cabinet, which would include several members of opposition parties. Also that year, representatives of opposition parties and other groups held a national conference to help Zaire move toward a democratic government. However, Mobutu broke up the conference several times.

In 1992, the conference elected Etienne Tshisekedi, a Mobutu opponent, as prime minister. That year, the conference also elected a legislature. But Mobutu did not give Tshisekedi’s government any real authority. In 1993, Mobutu dismissed Tshisekedi, and a new prime minister was appointed. But a defiant Tshisekedi, supported by the legislature, refused to accept the dismissal. Fighting broke out in southeastern Zaire between supporters and opponents of Mobutu. In January 1994, Mobutu again dismissed the prime minister. He also dissolved the legislature and formed a new one. A new prime minister was elected by the legislature in June, but Tshisekedi refused to recognize the election.

In 1994, more than 1 million Hutu refugees fled to eastern Zaire to escape Tutsi forces in Rwanda who had taken control of Rwanda’s government. The refugee camps in Zaire soon fell under the control of Hutu extremist militias, many of whom had been responsible for that year’s genocide (systematic killing) of about 800,000 people, mostly Tutsi, in Rwanda. In 1996, the Hutu extremists began attacking Tutsi in Zaire with the support of Zairian soldiers. Tutsi militias fought back with the support of Rwanda and Uganda.

Later in 1996, the movement to defend the Tutsi in eastern Zaire grew into a national rebellion against the Mobutu government. The rebels, backed mainly by Rwanda, won a series of victories and pushed westward. During their march toward Kinshasa, they slaughtered tens of thousands of Hutu refugees. In May 1997, Mobutu fled the country, and the rebel forces entered Kinshasa. Rebel leader Laurent Kabila then declared himself president and established a transitional government. He renamed the country the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Mobutu died of cancer in September 1997.

Cease-fires and power sharing.

The Kabila government failed to expel the Hutu extremist militias from the DRC. Rwanda and Uganda saw these extremists as a threat to their national security. In 1998, Congolese rebels backed by Rwanda and Uganda began a war in eastern Congo against the Kabila government. Forces from Angola, Namibia, and Zimbabwe fought on the side of Kabila. The rebels established control over much of eastern Congo but failed to seize Kinshasa. The two main rebel groups were the Rwandan-backed Congolese Rally for Democracy (RCD) and the Ugandan-backed Movement for the Liberation of Congo (MLC).

In 1999, a cease-fire agreement was signed by the DRC, the other countries involved in the war, and the two rebel groups. In 2000, the UN authorized a peacekeeping force to monitor the cease-fire. However, the agreement was violated by all the countries and rebel groups, and fighting continued.

In 2001, Kabila was assassinated by one of his bodyguards. Kabila’s son Joseph succeeded him as president. The younger Kabila tried to establish peace and allowed the UN force to take up positions throughout Congo. Later in 2001, troops from both sides of the war began to withdraw from front-line positions. Most Rwandan troops, however, did not withdraw.

In April 2002, the Congolese government signed a power-sharing agreement with the MLC. In July, Congo and Rwanda signed an agreement that called for Rwanda to withdraw its troops and for Congo to disarm the Hutu militias. In September, Congo and Uganda signed a similar peace agreement. By October, nearly all foreign troops on both sides of the war, including all Rwandan troops, had left Congo.

In December, the Kabila government signed a power-sharing agreement with the RCD, the MLC, and political opposition groups. Under the agreement, Kabila remained president, and in 2003, he appointed a transitional government with four vice presidents—one for the RCD, one for the MLC, one for Kabila supporters, and one for the political opposition.

Some fighting continued in parts of eastern Congo. In mid-2003, clashes between rival ethnic militias in and around the city of Bunia resulted in the deaths of hundreds of people. A French-led international emergency force was sent to the area to help stop the violence. UN peacekeepers later replaced the French-led force. In mid-2004, rebels from the RCD briefly captured the city of Bukavu. Violence again broke out in late 2004 between the Congolese army and soldiers loyal to the RCD. In 2005, there were more outbreaks of violence, involving ethnic militias, Congolese troops, UN forces, and Hutu rebels from Rwanda.

Tensions remain high among the various groups in the area, and between the DRC and Rwanda. Since 1998, there have been nearly 4 million conflict-related deaths in Congo, mostly from disease and malnutrition.

New government.

In 2005, the parliament approved a new constitution for the country, and voters approved the Constitution in a national referendum. The government officially adopted the Constitution in February 2006.

On July 30, 2006, the Congolese people voted in the first multiparty parliamentary and presidential elections there since 1965. However, no presidential candidate received over half of the votes. In October 2006, Congo held a runoff election between the two leading presidential candidates, Joseph Kabila and Jean-Pierre Bemba. The elections were peaceful, but fighting after the elections between supporters of Kabila and Bemba led to the deaths of over 20 people. Preliminary election results showed Kabila as the winner. Bemba challenged the results in Congo’s Supreme Court, but the court upheld the results. Kabila was sworn in as president in December.

In January 2008, the Congolese government, rebel groups, the European Union, the United Nations, and the United States signed a cease-fire agreement aimed at ending the violence in eastern Congo. Some fighting continued, but the rebel groups maintained their commitment to the peace process. In August, fighting increased, displacing about 250,000 people.

In December 2008, the Ugandan rebel group the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) crossed into Congo and began launching attacks. The Congolese government gave the Ugandan army permission to hunt for the LRA within Congo. Over the next several months, the LRA killed an estimated 900 people in Congo. The United Nations, which already had a substantial presence in the DRC, sent an additional 1,000 peacekeepers to the country to help protect Congolese citizens. Uganda’s army pulled out of the country in 2009. The United Nations began reducing its peacekeeping force in the country in 2010. Joseph Kabila was reelected in 2011. In 2013, the United Nations created an “intervention brigade” to address the continued problem of armed rebels in the DRC.

In 2016, the country’s Constitutional Court ruled that Kabila could remain in office if elections scheduled for November did not take place. International observers expressed concern that Kabila would intentionally delay the elections to stay in power. Later that year, the government announced the elections would be delayed until 2018 because of problems with voter registration. After the 2018 elections, Felix Tshisekedi was declared the winner, the first time an opposition candidate had won an election in the DRC since the country became independent in 1960. Kabila stepped down after 18 years in office, and Tshisekedi was sworn in as president in January 2019.

An outbreak of the deadly Ebola virus disease (EVD) was detected in Congo in July 2018. By the time the outbreak was contained in June 2020, the Ebola virus had infected more than 3,400 people and caused the deaths of more than 2,200 in northeastern Congo. It was the second worst outbreak of EVD in Africa, after the widespread outbreak of 2013 to 2016.

In 2020, Congo faced a new public health crisis as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic (worldwide epidemic). COVID-19 is a sometimes fatal respiratory disease caused by a coronavirus. Congo confirmed its first case of COVID-19 in March. The government quickly declared a state of emergency. It also closed the country’s borders and prohibited travel in and out of Kinshasa, the center of the country’s epidemic. As in other nations, such containment measures strained the economy. The DRC began distributing COVID-19 vaccines in April 2021. By April 2023, more than 95,000 of Congo’s people had been infected with the virus, and more than 1,400 had died from the disease.

In May 2021, Mount Nyiragongo, a volcano just north of the city of Goma in eastern Congo, erupted. About 400,000 people were evacuated from the city, some of whom fled across the border into Rwanda. More than 30 others were killed, and hundreds of homes were destroyed.

In December 2023, President Tshisekedi was reelected. Opposition candidates and their supporters disputed the results of the election.