Congress of the United States makes the nation’s laws. Congress consists of two bodies, the Senate and the House of Representatives. Both bodies have about equal power. The people elect the members of Congress.

Although Congress’s most important task is making laws, it also has other major duties. For example, the Senate approves or rejects the U.S. president’s choices for the heads of government departments, Supreme Court justices, and certain other high-ranking jobs. The Senate also approves or rejects treaties that the president makes.

Each member of Congress represents many citizens. Therefore, members must know the views of the voters and be guided by those views when considering proposed laws. Being a member of Congress also means answering citizens’ letters, appearing at local events, and having local offices to handle people’s problems with the government.

This article provides a broad description of Congress. For more information, see the separate World Book articles House of Representatives and Senate.

How Congress is organized

Congress is a bicameral (two-chamber) legislature. The 100-member Senate consists of 2 senators from each of the 50 states. The House of Representatives, usually called simply the House, has 435 members. House members, or representatives, are elected from congressional districts of about equal population into which the states are divided. Every state must have at least one House seat. Representatives are often called congressmen or congresswomen, though technically the titles also apply to senators.

The Democratic and Republican parties have long been the only major political parties in Congress. In each house of Congress, the party with more members is the majority party. The other one is the minority party. If a chamber is evenly split between the two parties, it has neither a majority nor a minority party. Before every new session of Congress, Republicans and Democrats in each house meet in what is called a caucus or conference to choose party leaders and to consider legislative issues and plans.

Committees form an important feature of each chamber’s organization. They prepare the bills to be voted on. The committee system divides the work of processing legislation and enables members to specialize in particular types of issues. The majority party in each chamber elects the head of each committee and holds a majority of the seats on most committees.

The Senate.

According to Article I, Section 3 of the Constitution, the vice president of the United States serves as head of the Senate with the title president of the Senate. However, the vice president is not considered a member of that body and rarely appears there, except on ceremonial occasions or to break a tie vote. The Senate elects a president pro tempore (temporary president) to serve in the vice president’s absence. The Senate usually elects the majority party senator with the longest continuous service. The president pro tempore signs official papers for the Senate but presides infrequently. Most of the time, the president pro tempore appoints a junior senator as temporary president.

Democrats and Republicans each elect a chief officer called a floor leader. A floor leader is also known as the majority leader or the minority leader, depending on the senator’s party. Each party elects an officer called a whip to assist the floor leaders. Floor leaders or whips are typically at their desks at the front of the chamber. They arrange the Senate’s schedule, work for passage of their party’s legislative program, and look after the interests of absent senators.

All senators treasure their right to be consulted on bills, to offer amendments, and to speak at length in debate. Just one senator can slow down or halt the work of the Senate. Thus, Senate leaders spend much time considering fellow senators’ needs and arranging compromises that will enable the work of the chamber to go on.

The Senate makes laws with the help of 16 permanent standing committees. In addition, the Senate has select and special committees that were formed for special purposes. Most committees have subcommittees to handle particular topics. Typically, a senator sits on about four committees and six subcommittees.

The House of Representatives.

The speaker of the House, mentioned in Article I, Section 2 of the Constitution, serves as presiding officer and party leader. The majority party nominates the speaker, who is then elected by a party-line vote of the entire House. The speaker is the most important member of Congress because of the office’s broad powers. The speaker refers bills to committees, names members of special committees, and nominates the majority party’s members of the powerful Rules Committee. The speaker votes in case of ties and grants representatives the right to speak during debates. With the help of assistants, the speaker also influences committee assignments, arranges committee handling of bills, and schedules bills for House debate. As in the Senate, the House majority and minority parties each choose a floor leader and a whip.

The House has 20 standing committees and 1 permanent select committee. Except under certain circumstances, a representative is limited to serving on 2 standing committees and 4 subcommittees.

When Congress meets.

A new Congress is organized every two years, after congressional elections in November of even-numbered years. Voters elect all the representatives, resulting in a new House of Representatives. About a third of the senators come up for election every two years. The Senate is a continuing body because it is never completely new. Beginning with the First Congress (1789-1791), each Congress has been numbered in order. The lawmakers elected in 2022 made up the 118th Congress.

Congress holds one regular session a year. The session begins on January 3 unless Congress sets a different date. During the year, Congress recesses often so members can visit their home states or districts. Congress adjourns in early fall in election years and in late fall in other years. After Congress adjourns, the president may call a special session. The president may adjourn Congress only if the two houses disagree on an adjournment date.

The Senate and the House meet in separate chambers in the Capitol in Washington, D.C. The building stands on Capitol Hill, often called simply the Hill. Senators and representatives occasionally meet in a joint session in the larger House of Representatives chamber, mainly to hear an address by the president or a foreign official. The Constitution requires Congress to meet jointly to count the electoral votes after a presidential election. Legislation is never acted on in a joint session.

Congress’s power to make laws

Origin of power.

The Constitution gives Congress “all legislative powers” of the federal government. At the heart of Congress’s lawmaking powers is its “power of the purse”—its control over government taxing and spending. Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution lists a wide range of powers granted to Congress. These delegated, or expressed, powers include the authority to coin money, regulate trade, declare war, and raise and equip military forces.

Article I, Section 8 also contains an elastic clause that gives Congress authority to “make all laws which shall be necessary and proper” to carry out the delegated powers. The elastic clause grants Congress implied powers to deal with many matters not specifically mentioned in the Constitution. For example, Congress has the expressed power to coin money. It has the implied power to create a treasury department to print money.

Limitations of power.

Congress is limited in the use of its powers. The Constitution prohibits some types of laws outright. For example, Congress may not pass trade laws that favor one state of the United States over another. The Bill of Rights, the first 10 amendments to the Constitution, forbids certain other laws. For instance, the First Amendment bars Congress from establishing a national religion; preventing religious freedom; or limiting freedom of speech, press, assembly, or petition.

The executive and judicial branches of government also limit Congress’s powers. The president may veto any bill Congress passes. Congress can override (reverse) a veto only by a two-thirds vote in each chamber, which is usually difficult to obtain. The president’s power to propose legislation acts as another check on Congress. By its implied power of judicial review, the Supreme Court may declare a law passed by Congress to be unconstitutional. The courts also shape laws through their interpretations of them.

Finally, the power of public opinion limits what Congress can do. Lawmakers know that their actions must, in general, reflect the will of the people.

How Congress makes laws

Congress passes and the president signs about 600 laws during every two-year Congress. During that period, senators and representatives introduce up to 10,000 bills. The legislative process sifts the proposals at every stage in the development of a bill to a law. To be enacted, a bill must survive committee and floor debates in both houses. It often must win the support of special-interest groups, or lobbies. A lobby represents a particular group, such as farmers or labor unions, and tries to influence legislators to pass laws favorable to that group. A bill must also gain a majority of votes in Congress and the president’s signature. If the president vetoes the bill, it needs overwhelming support in Congress to override the veto.

Proposing new laws.

Laws can be proposed by anyone, including lawmakers or their staffs, executive officials, or special-interest groups. The president can propose laws in speeches or public appearances. At a national convention, a political party may suggest laws to reflect the party’s position on major issues. But to become a law, a bill must be sponsored and formally introduced in Congress by a member. Any number of senators or representatives may co-sponsor a bill.

A bill may be public or private. A public bill deals with matters of concern to people in general. Such matters include taxation, national defense, and foreign affairs. A private bill applies only to specific individuals, as in an immigration case or a claim against the government. To become a law, either kind of bill must be passed in exactly the same form by both houses of Congress and then signed by the president. Each proposed bill is printed and assigned a number, such as S. 1 in the Senate and H.R. 1 in the House of Representatives. Bills are also often known by popular names or by the names of their sponsors or authors.

Working in committees.

After being introduced, a bill goes to a committee that deals with the matters the bill covers. Some bills involve various subjects and may be handled by several committees. For example, a trade bill may include sections on taxes, commerce, and banking. The bill may thus interest congressional tax, commerce, and banking committees.

The chief congressional committees are the 16 Senate and the 20 House standing committees. They handle most major fields of legislation, such as agriculture, banking, foreign policy, and transportation. Most standing committees have subcommittees, which hold hearings and work on bills on specialized matters.

The select and special committees of Congress propose laws on particular subjects or conduct investigations. In 1987, for example, each house appointed a select committee to examine the Iran-contra affair. The affair involved the sale of U.S. weapons to Iran in exchange for hostages, and the use of profits from the weapons sale to help the contra rebel forces in Nicaragua. Joint committees have members from both the House and the Senate. Such committees handle mainly research and administrative matters.

A proposed law reaches a critical stage after being referred to a committee. Committees report (return) only about 15 percent of all bills they receive to the full Senate or House for consideration. Most bills are tabled, or pigeonholed—that is, never acted on. A committee’s failure to act on a bill almost always spells death for the measure.

If committee leaders decide to proceed with a bill, they usually hold public hearings to receive testimony for and against the proposal. Testimony may be heard from a range of people, such as members of the president’s Cabinet, scholars, representatives of special-interest groups, or lawmakers themselves.

Some bills go from committee to the full House or Senate without change. But most bills must be revised in committee markup sessions. In a markup session, members debate the sections of a measure and write amendments, thereby “marking up” the bill. When a majority of the committee’s members vote for the revised bill, they report it to the full chamber with the recommendation that it be passed.

Legislative bargaining.

To gain passage of a congressional bill, its sponsors must bargain for their fellow lawmakers’ support. They need to give other legislators good reason to vote for the measure. To win a majority vote, the bill must be attractive to members with widely differing interests. Skillful legislators know how to draft a bill with broad appeal.

In a bargaining technique called compromise, legislators agree to take a position between two viewpoints. For example, lawmakers who want a major new government program and those who oppose any program at all might agree on a small trial project to test the idea.

In another form of legislative bargaining, called pork barrel, a bill is written so that many lawmakers benefit. For instance, a 1987 highway bill in the House included projects in so many members’ districts that few representatives dared vote against it.

Some congressional bargaining involves an exchange of support over time. Lawmakers may vote for a fellow member’s bill expecting that they will need that person’s support later on another measure. This mutual help in passing bills is called logrolling.

In other instances, a member who is ill-informed on a bill may follow the lead of a lawmaker who is an expert on the subject. Some other time, the influence may flow the other way. This technique is called cue giving and cue taking. Lawmakers cannot be experts on every bill. They rely on associates who have worked on the bill.

Passing a bill.

After a committee reports a bill, it is placed on a calendar (list of business) of whichever house of Congress is considering it. The Senate assigns all public and private bills to one calendar. It has a separate calendar for matters originating in the executive branch, such as treaties and presidential appointments. The House has four regularly used calendars. They involve (1) bills that raise or spend money, (2) all other major public bills, (3) private bills, and (4) noncontroversial bills.

Committees screen out bills that lack broad support. Therefore, most measures that reach the House or Senate floor for debate and voting eventually pass. The Senate usually considers a bill by a simple motion or by unanimous consent—that is, without anyone’s objection. The objection of one senator can block unanimous consent, and so Senate leaders work to make sure the bill is acceptable to their associates. Senators, however, cherish their tradition of free and sometimes lengthy debate. Senators opposed to a bill may make filibusters—long speeches designed to kill the bill or force its sponsors to compromise. To halt a filibuster, the Senate can vote cloture—that is, to limit the debate.

The House considers most bills by unanimous consent, like the Senate, or by the suspension-of-rules procedure. Both methods speed up legislation on largely noncontroversial bills. Representatives consider controversial bills under rules made by the Rules Committee. The rules control debate on a bill by setting time limits, restricting amendments, and, occasionally, barring objections to sections of the bill. Debate time is divided between the bill’s supporters and opponents.

Legislators use various methods to vote on a bill. In a voice vote, all in favor say aye together, and those opposed say no. In division, the members stand as a group to indicate if they are for or against a bill. In a roll-call vote, the lawmakers each vote yes or no after their name is called. The House usually records and counts votes electronically. Members vote by pushing a button.

Senators and representatives tend to vote according to their party’s position on a bill. If legislators know the views of their constituents (the people who elected them), they may vote accordingly. The president and powerful lobbies also influence how members vote.

From bill to law.

After a bill passes one house of Congress, it goes to the other. The second house approves many bills without change. Some bills go back to the first house for further action. At times, the second house asks for a meeting with the first house to settle differences. Such a conference committee brings together committee leaders from both chambers to decide on the final bill. The two chambers then approve the bill, and it is sent to the president.

The president has 10 days—not including Sundays—to sign or veto a bill after receiving it. The veto is most powerful when used as a threat—lawmakers working on a bill want to know if the president is likely to approve it. If the president fails to sign or return the bill within 10 days and Congress is in session, the bill becomes law. But if Congress adjourns during that time, the bill does not become law. Such action is called a pocket veto.

Presidents veto about 3 percent of the bills they get. Congress overrides only about 4 percent of all vetoes. Presidents may veto a bill because it differs from their legislative program, or because they feel it is unconstitutional, costs too much, or is too hard to enforce. See Veto.

Other duties of Congress

Passing laws lies at the heart of Congress’s duties. But Congress also has nonlegislative tasks that influence national government and shape public policies.

Approving federal appointments.

The Constitution requires the president to submit nominations of Cabinet members, federal judges, ambassadors, and certain other officials to the Senate for approval. A majority vote of the senators present confirms a presidential appointment. Senators approve almost all nominations to the executive branch because they believe that the president deserves loyal people in top jobs. The Senate examines judicial appointments more critically. About a fourth of all Supreme Court nominees have failed to win Senate confirmation. Some were rejected by a vote, but more commonly the Senate delayed acting on the nomination, often leading the president to withdraw it.

Approving treaties.

According to Article II, Section 2 of the Constitution, the president has the power to make treaties “by and with the advice and consent of the Senate.” A treaty requires the approval of two-thirds of the senators voting on it. The Senate has rejected very few treaties since the First Congress met in 1789.

The most famous treaty rejection was the Senate’s refusal to approve the Treaty of Versailles, which established peace with Germany at the end of World War I (1914-1918). The treaty included President Woodrow Wilson’s proposal for the League of Nations, an international association to maintain peace. Senators proposed reservations to the treaty—particularly the League—but Wilson rejected them, leading to the treaty’s downfall.

In recent years, presidents have tried to keep the Senate informed as they arrange treaties. For example, President Ronald Reagan invited senators to follow negotiations for the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty, which called for the elimination of certain U.S. and Soviet nuclear weapons. Objections from the senators sent U.S. diplomats back to the bargaining table to revise the treaty. Signed in December 1987, the treaty won Senate approval by the following May.

Conducting investigations.

Congress has the implied power to investigate executive actions and public and private wrongdoing because such inquiries may lead to new laws. Congressional committees conduct the investigations. Congress has launched investigations to uncover scandals, spotlight certain issues, embarrass the president, or advance the reputations of the lawmakers themselves. Televised congressional investigations have aroused great public interest and highlighted Congress’s role in keeping the people informed. An early televised investigation took place in 1954, when millions of TV viewers watched Senator Joseph R. McCarthy charge the U.S. Army with “coddling Communists.”

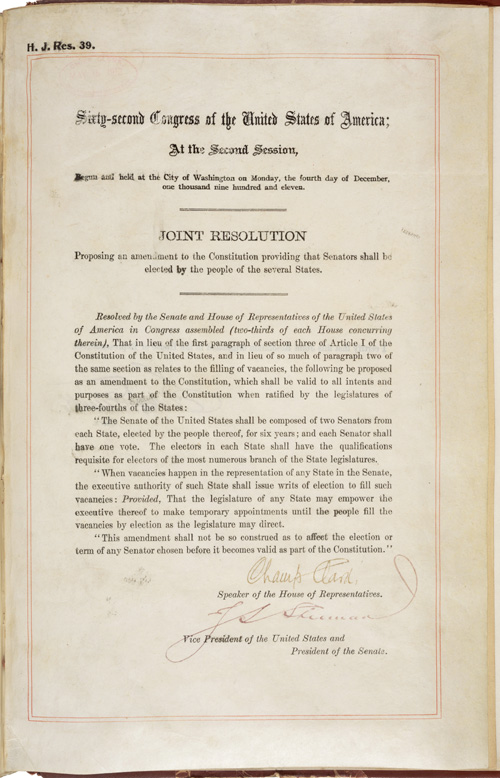

Proposing constitutional amendments.

Congress can propose amendments to the U.S. Constitution by a two-thirds vote in both houses. Congress can also call a constitutional convention to propose amendments if at least two-thirds of the states formally request it. In addition, Congress determines whether the states vote on an amendment by means of state legislatures or special state conventions. Congress also decides how long the states have to consider an amendment. It allows seven years in most cases.

Handling presidential election results.

Congress counts and checks the votes cast by the Electoral College, the group of electors that chooses the U.S. president and vice president. Congress then announces the results of the election. In most cases, the public knows the winners from the outcome of the popular election. If no candidate has a majority of Electoral College votes, Congress selects the winners. The House chooses the president, and the Senate elects the vice president.

Impeaching and trying federal officials.

An impeachment is a charge of serious misconduct in office. The House of Representatives has the power to draw up charges of impeachment against officials of the national government. If a majority of representatives vote for impeachment, the Senate then sits as a court to hear the charges against the accused official. Impeachments rarely occur. The House voted to impeach President Andrew Johnson in 1868, but the Senate narrowly acquitted him. President Richard M. Nixon resigned in 1974 before representatives voted on impeachment charges recommended by the House Judiciary Committee. In 1998, Bill Clinton became the second president to be impeached. However, the Senate acquitted him the following year. The House voted to impeach President Donald J. Trump twice, in 2019 and again in 2021. The Senate, however, acquitted him both times.

Reviewing its own members.

Congress can review the election and judge the qualifications of its own members. It can also censure (officially condemn) or expel members for improper conduct as well as apply a milder form of discipline, such as a fine or reprimand. Congress has censured members for such reasons as the conviction of crimes, unethical (morally wrong) conduct, or disgracing Congress.

Members of Congress at work

A typical day.

The daily schedule of members of Congress reflects their jobs both as lawmakers and as representatives for their districts and states. Most members work at least 11 hours a day. Mornings involve office work and committee meetings, often with two or three meetings scheduled at the same time. Members choose which meeting to attend. They make brief appearances at other meetings or send aides to take notes. During the afternoon, and many mornings and evenings, the Senate and House are in session. Most legislators, busy with other work, do not stay in their particular chamber for debates. Instead, they follow them on closed-circuit TV. Members must be ready to go to their chamber for a vote or a quorum call—that is, a count taken to determine if the minimum number of lawmakers needed to hold a vote is present.

Telephone calls, letters, and visits from constituents take up much of a legislator’s time. Many people contact members of Congress to give their views on bills. Other people seek help with jobs, immigration problems, social security payments, or appointments to military academies.

Senators and representatives have assistants in their Washington, D.C., offices and in their state or district offices. The size of a senator’s staff depends on the population of the senator’s state—the larger the population, the larger the staff. The average staff consists of about 40 to 50 people. By law, representatives may employ up to 18 aides. Party and committee leaders in Congress have additional aides. Most members also accept students who work without pay to gain political experience. The students work either in Washington or in local offices on legislation and relations with constituents.

Congressional travel.

Members of Congress travel often to their home states or districts to appear at public events, study area problems, and talk with voters or local officials. In fact, about a third of all representatives return to their districts nearly every weekend. Sessions of the Senate and House are scheduled to accommodate the members’ need to appear frequently before their constituents, and legislators receive allowances to cover their expenses. If members fail to visit their home states or districts fairly often, they are apt to be criticized for forgetting their constituents.

Fact-finding missions at home or abroad—sometimes called junkets—also crowd the schedules of senators and representatives. Critics charge that legislators enjoy foreign travel at public expense. Legislators argue that experience gained by travel abroad helps them understand world developments and legislate wisely.

Social responsibilities.

Membership in Congress carries many social obligations. Both at home and in Washington, individuals and groups interview legislators and expect them to attend social events.

History of Congress

The founding of Congress

grew out of a tradition of representative assemblies that was brought from the United Kingdom and took root in the American Colonies in the early 1600’s. Colonial assemblies had a wide range of powers, including authority to collect taxes, issue money, and provide for defense. In time, the assemblies increasingly voiced the colonists’ interests against those of the British-appointed colonial governors.

As tensions worsened between the United Kingdom and the American Colonies in the 1760’s, the colonial assemblies took up the colonists’ cause. The First Continental Congress met in Philadelphia in 1774. It drew lawmakers from every colony but Georgia and could be considered the colonists’ first “national” assembly. In 1776, the Second Continental Congress declared the colonies’ independence from the United Kingdom. It served as a temporary national government until 1781, when the states adopted the Articles of Confederation and set up a national legislature called the Congress of the Confederation. This body functioned without an independent executive or judicial branch and soon showed its weakness.

In 1787, the Constitutional Convention met to strengthen the Articles of Confederation. But the delegates drew up a new plan of government instead—the Constitution of the United States. The power of the legislature remained important, but it was balanced by executive and judicial branches. The Constitution called for two chambers for the new Congress—earlier Congresses had one house—with equal representation in one chamber and representation by population in the other. The establishment of a two-house legislature became known as the Great Compromise. It solved a bitter dispute between delegates from small states, who favored equal representation for every state, and those from large states, who wanted representation based on state population.

Growth and conflict.

When the new Congress met for the first time in New York City in 1789, the two chambers were small and informal. At the end of the First Congress, the Senate had only 26 members, and the House of Representatives 65. As new states joined the Union, the House grew faster than the Senate and developed strong leaders. Such House speakers as Henry Clay in the early 1800’s and Thomas B. Reed in the late 1800’s brought power and high honor to their office. They also increased the power of the House of Representatives. The Senate enjoyed a golden age from about the 1830’s to the 1860’s, when it had such great speechmakers as Clay, Daniel Webster, and John C. Calhoun. Those men and their fellow senators debated the existence of slavery in the United States and other burning issues of the day.

Relations between Congress and the president shifted wildly throughout the 1800’s. Most presidents yielded to Congress and initiated few policies. During the early and middle 1800’s, however, several strong presidents sought to deal with Congress as an equal. Thomas Jefferson worked with congressional supporters to enact legislation drafted by the executive branch. Andrew Jackson promoted his policies through patronage—that is, his authority to make federal job appointments—and through his use of the veto. Abraham Lincoln used emergency authority to force Congress to accept his policies during the American Civil War (1861-1865).

Congress recaptured power after each of the strong presidents. Following the Civil War, the House ruled supreme, and the speaker became almost as important as the president. The speaker became so strong that House members revolted in 1910 to limit the office’s power.

Continued struggle for power.

During the early to middle 1900’s, voters elected several strong-willed individuals who established the president as a leader in the legislative process. These men included Presidents Theodore Roosevelt, Woodrow Wilson, and especially Franklin D. Roosevelt. Each proposed a package of new laws and worked to persuade or pressure Congress to enact that package. Congress began to rely increasingly on its committees to process legislation.

Relations between Congress and the presidency changed markedly in the late 1960’s and early 1970’s. Such events as the Vietnam War (1957-1975) and the Watergate scandal led Congress to limit the president’s authority. The Vietnam War had never been officially declared by Congress. But Presidents Lyndon B. Johnson and Nixon, as commanders in chief of the nation’s armed forces, had sent hundreds of thousands of U.S. troops into the conflict. Public opposition to the war spurred Congress to pass the War Powers Resolution in 1973 over Nixon’s veto. The resolution restricts the president’s authority to keep U.S. troops in a hostile area without Congress’s consent. The law reasserted Congress’s role in foreign affairs but has had mixed success in curbing the president’s warmaking authority.

In 1973, a Senate select committee began hearings on the Watergate scandal. The scandal involved illegal campaign activities during the 1972 presidential race. The investigation led the House to begin impeachment proceedings against President Nixon. In July 1974, the House Judiciary Committee voted to recommend three articles of impeachment against Nixon—for obstructing justice, abusing presidential powers, and illegally withholding evidence. Nixon resigned in August 1974, before the full House voted on the three charges. Congress further declared its authority in 1974, when it passed an act that restricts the president’s freedom to impound (refuse to spend) funds for projects approved by Congress.

In 1996, Congress took the unusual step of trying to increase presidential power. It did so by passing a law to enable the president to veto some items in spending bills. The new power, known as the line-item veto, went into effect in 1997. Many members of Congress voted for the bill because they thought presidents might use it to block unneeded spending that Congress, under pressure from local groups, often included in federal legislation. In 1998, however, the Supreme Court ruled the line-item veto unconstitutional.

Later that year, the Republican-controlled House impeached President Bill Clinton, a Democrat. The House charged Clinton with perjury and obstruction of justice. The charges stemmed from Clinton’s efforts to deal with a federal investigation of an extramarital affair he had while in office. The Senate, also controlled by Republicans, acquitted Clinton of both charges in 1999. See Clinton, Bill.

In 2019, the Democrat-controlled House voted to impeach Donald J. Trump on charges of (1) abuse of power, for urging a foreign power to investigate a domestic political rival; and (2) obstruction of Congress, for hindering congressional investigators. However, in 2020, the Republican-led Senate, voting almost entirely along party lines, acquitted him. In 2021, Trump was impeached again, for “incitement of insurrection,” after violent pro-Trump rioters stormed the U.S. Capitol. But the Senate acquitted him weeks after he left office. See Trump, Donald J.

Congressional ethics

has gained public attention since the late 1900’s. In 1989, for example, House Speaker James C. Wright, Jr., resigned his seat after being accused of accepting improper gifts and of earning more income from outside sources than House rules permitted. Public criticism of the House increased in 1991, when it was discovered that many House members had regularly overdrawn their accounts at the House bank. The practice involved no public funds, but the issue drew criticism of privileges enjoyed by Congress. The U.S. Justice Department later brought criminal charges against several former House members, their relatives, and House employees, for misuse of the bank and other improper financial dealings. Some received prison sentences. In 1994, Representative Dan Rostenkowski was indicted on corruption charges and was forced to resign as chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee. In 1996, he pleaded guilty to some of the charges and was sentenced to 17 months in prison. In 1995, Senator Bob Packwood resigned after the Senate Ethics Committee recommended his expulsion based on sexual harassment and other charges.

In 1997, Newt Gingrich became the first House speaker ever to be reprimanded by the House of Representatives. The House reprimanded Gingrich, and fined him $300,000, for using tax-exempt donations for political purposes and for giving the House Ethics Committee false information when it asked him about the contributions. In 2002, Representative James A. Traficant, Jr., was expelled from the House after being convicted on charges of bribery, racketeering, and tax evasion. A federal judge sentenced Traficant to eight years in prison.

In 2005, Representative Randy “Duke” Cunningham resigned after confessing to taking bribes from defense contractors and to evading income taxes. In 2006, Representative Bob Ney resigned from Congress after pleading guilty to conspiracy and making false statements in relation to a political corruption scandal. Earlier that year, Federal Bureau of Investigation agents raided the congressional office of Representative William Jefferson. In 2009, a federal judge sentenced Jefferson to 13 years in prison after finding Jefferson guilty of taking bribes, money laundering, and other charges.

In 2023, the House voted to expel Representative George Santos from Congress. At the time of his expulsion, Santos faced numerous federal criminal charges, including wire fraud, money laundering, theft of public funds, and making false statements to investigators. Santos, who admitted that he had falsified many details about his educational and employment history, had also been the subject of an investigation by the House Ethics Committee.

Many people have objected to Congress’s ability to vote itself pay raises. In 1992, to limit this ability, the last of the required number of states ratified the 27th Amendment to the Constitution of the United States. This amendment requires that whenever a raise is authorized, it may not take effect until after the next congressional election.

The soaring cost of congressional campaigns has led to growing public concern that members of Congress spend too much time raising money and that large donors have too much influence on policy decisions. Big donors include political action committees (PAC’s). A political action committee obtains voluntary contributions from members or employees of a special-interest group and gives the funds to candidates it favors.