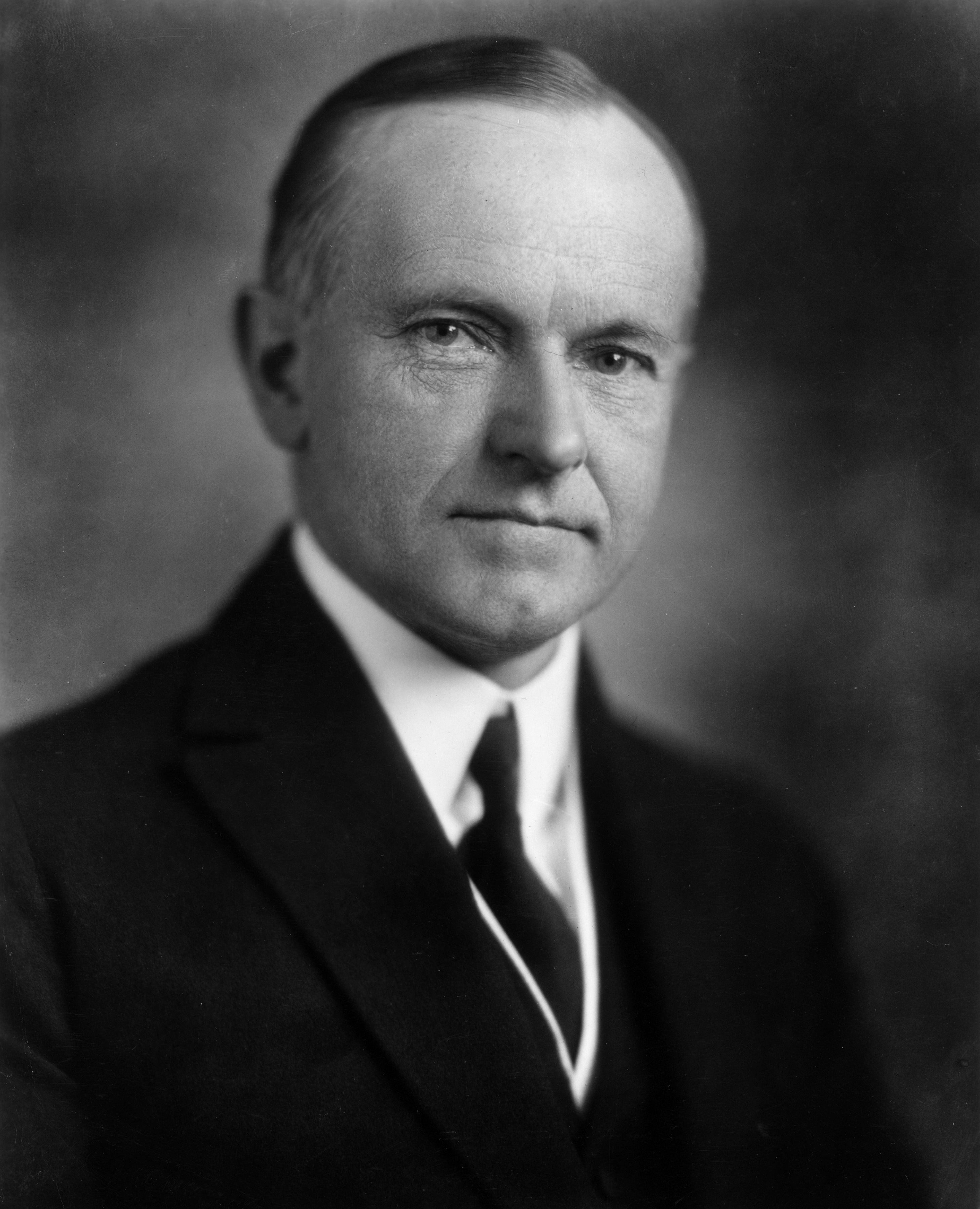

Coolidge, Calvin (1872-1933), was a shy, somber New England Republican who led the United States during the boisterous Jazz Age of the 1920’s. Coolidge, as vice president, was vacationing on his father’s farm in Vermont in August 1923 when he was notified that President Warren G. Harding had died. This made Coolidge the sixth vice president to become president upon the death of a chief executive. Coolidge’s father, a notary public, administered the oath of office to his son in the family parlor. Never before had this ceremony been performed by such a minor official or by a president’s father. Because administration officials were convinced that the elder Coolidge did not have the authority to swear in a federal officer, the oath was later administered by a federal judge.

In 1924, Coolidge was elected to a full four-year term, winning a landslide victory. Throughout the next four years, he enjoyed great popularity. His decency was reassuring to the nation after the scandalous Harding years, and his reputation for wisdom was based on his common sense and dry wit. His nickname “Silent Cal” made him appear thoughtful rather than talkative.

Coolidge was president during the Roaring Twenties. Prosperity stimulated carefree behavior and a craving for entertainment. The nation’s “flaming youth,” featured in the novels of F. Scott Fitzgerald, set the pace. Sports figures became national heroes as Babe Ruth hit 60 home runs in one season and Gene Tunney defeated Jack Dempsey in the famous “long-count” bout. Charles A. Lindbergh made the first solo flight across the Atlantic Ocean. Motion pictures began to talk, with Al Jolson starring in The Jazz Singer. George Gershwin brought jazz into the concert hall with his Rhapsody in Blue. Americans defied Prohibition, and Al Capone and other gangsters grew rich by bootlegging liquor. A popular song summed up the spirit of the whole era: “Ain’t We Got Fun?”

Coolidge’s straight-laced frugality seemed to belong to another era. But people admired him even if many of them did not imitate his conduct. They respected him for having the virtues of their pioneer ancestors.

Early life

Childhood.

Calvin Coolidge was born on July 4, 1872, in Plymouth Notch, a village near Woodstock in central Vermont. He was named for his father, John Calvin Coolidge, but his parents called him Calvin, or Cal. He soon dropped the name John and became known simply as Calvin Coolidge.

Calvin’s father was descended from an English family that came to America about 1630. When Calvin was 4 and his sister, Abigail, was 1, his father bought a small farm across the road from the family store. Cal helped with the farm chores and studied in a small, cold stone schoolhouse nearby.

The elder Coolidge was a respected figure in the local community. He served three terms in the Vermont House of Representatives and one term in the state Senate, and held many local public offices. He stressed to his children the importance of frugality and hard work. Calvin’s mother, Victoria Josephine Moor Coolidge, died when he was 12 years old.

Education.

A year after his mother’s death, Calvin entered Black River Academy at nearby Ludlow and was joined there by his sister, Abigail, two years later. She died of apparent appendicitis a short time before his graduation in 1890, leading the shy Coolidge to comment on his loneliness without her. He took a short course at St. Johnsbury Academy and entered Amherst College in 1891.

As a college student, Coolidge initially was seen by his peers as a country bumpkin but eventually impressed them with his humor and debating prowess. He earned only fair grades during his first two years, but graduated cum laude in 1895.

Coolidge then read law with the firm of Hammond and Field in Northampton, Massachusetts. He passed that state’s bar examination in 1897, and about seven months later opened his own office in Northampton.

Political and public activities

Entry into politics.

Coolidge became active in Republican Party politics in 1896. He was appointed to the Republican City Committee in 1897 and was elected to the Northampton City Council in 1898. He became city solicitor in 1900, won reelection in 1901, but lost in 1902.

In 1904, Coolidge met his future wife, Grace Anna Goodhue (Jan. 3, 1879-July 8, 1957), a teacher at the Clarke School for the Deaf in Northampton. She was cheerful, talkative, and fun-loving—just the opposite of the quiet Coolidge—and a great political asset to him. Shortly after their marriage on Oct. 4, 1905, he arrived home from his office with a bag containing 52 pairs of socks, all with holes. When his bride asked if he had married her to darn his socks, Coolidge, with characteristic bluntness, replied: “No, but I find it mighty handy.” The Coolidges had two sons, John (1906-2000), who became a business executive, and Calvin, Jr. (1908-1924).

In 1905, Coolidge ran for the Northampton School Committee but was defeated. In 1906, he was elected to the Massachusetts House of Representatives, and he was reelected the next year. He won election as mayor of Northampton in 1909 and was returned to office in 1910. From 1912 to 1915, Coolidge served in the state Senate, with two terms as president of that body. He was elected lieutenant governor in 1915, and twice won reelection. He was elected governor in 1918.

As governor,

Coolidge supported a moderately progressive agenda and secured much of its passage. But it was the Boston Police Strike of 1919 that brought him national fame. In defiance of police department rules, a group of Boston police officers had obtained a union charter from the American Federation of Labor (AFL). Police Commissioner Edwin U. Curtis suspended 19 union leaders for insubordination, and the next day more than 1,100 of Boston’s 1,500 police officers went on strike.

Bands of hoodlums roamed Boston for two nights, smashing windows and looting stores. Coolidge mobilized the state guard, and order was restored. When Curtis indicated that the striking policemen had deserted their posts and would be replaced by new recruits, Coolidge announced that both he and the state’s attorney general agreed with him. Samuel Gompers, president of the AFL, protested that the rights of the policemen had been violated. In reply, Coolidge made his famous declaration: “There is no right to strike against the public safety by anybody, anywhere, any time.”

Coolidge won reelection in 1919 by a record vote. In 1920, he received some votes for the presidential nomination at the Republican National Convention that chose Senator Warren G. Harding of Ohio on the 10th ballot. The delegates gave Coolidge the vice presidential nomination on the first ballot. Harding, friendly and easy-going, and Coolidge, quiet and solemn, won an overwhelming victory over their Democratic opponents, Governor James M. Cox of Ohio and Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Vice president.

At Harding’s invitation, Coolidge regularly attended meetings of the Cabinet. He was one of few vice presidents to do so. Coolidge also worked hard at presiding over meetings of the U.S. Senate and impressed its members with his firmness and skill.

Even in the social whirl of Washington, Coolidge remained unchanged. He rarely smiled, almost never laughed, and sat silently through official dinners that he claimed to enjoy. At one affair, a woman told him she had bet that she could get more than two words out of him. Replied Coolidge: “You lose.”

Early on the morning of Aug. 3, 1923, Coolidge was awakened in his father’s house with the startling news of Harding’s death. By the light of a kerosene lamp, his father administered the presidential oath at 2:47 a.m. Later that morning, Coolidge returned to Washington, after first visiting his mother’s grave. Years afterward, when asked to recall his first thought upon becoming president, he replied: “I thought I could swing it.”

Eighteen days later, Coolidge had a second oath of office administered by Justice A. A. Hoehling of the Supreme Court of the District of Columbia. To avoid damaging the image of the “Homestead Inaugural,” Hoehling was asked never to reveal the ceremony, and no public mention was made of it for many years.

Coolidge’s administration (1923-1929)

Congressional leadership.

Coolidge’s first State of the Union address in December 1923 won widespread praise. In it, he declared: “Our national government is not doing as much as it legitimately can do to promote the welfare of the people.” He made more than 40 legislative requests, including calls for environmental legislation, expanded veterans care, tax cuts, an expanded civil service system, and a federal, Cabinet-level department of education and welfare. Although Congress passed several of his programs, Coolidge became more passive in dealing with the legislative branch during the remainder of his term.

Corruption in government.

Coolidge entered the White House just as the Teapot Dome and other scandals of the Harding administration became public. Coolidge made no effort to shield the guilty. He appointed a two-person bipartisan committee to investigate and prosecute any wrongdoing, and his own personal honesty was never questioned. In 1924, he forced the resignation of Attorney General Harry M. Daugherty and other high officials who had been connected with the scandals. See Harding, Warren Gamaliel (Government scandals).

“Constructive economy.”

Coolidge continued Harding’s policy of supporting American business at home and abroad. He favored a program of what he called “constructive economy” and declared that “the chief business of the American people is business.” Less noticed is that in the same speech, he also said that “it is only those who do not understand our people who believe that our national life is entirely absorbed by material motives.” The government continued high tariffs on imports in an effort to help American manufacturers. Although Congress reduced income taxes, revenue from taxes increased and the administration reduced the national debt by about a billion dollars a year. Congress also restricted immigration beyond what it had done in 1921. Coolidge vetoed the World War I veteran’s bonus bill, but Congress passed it over his veto.

Some economists warned that this period of prosperity would end in a severe depression. But most Americans believed that good times had come to stay. Coolidge did not try to stop the speculation, which contributed to the stock market crash of 1929, seven months after he left office.

Farmers did not share in the general prosperity. Farm prices had fallen, and the purchase of farm products by other nations had declined because of a worldwide surplus of agricultural products. Coolidge twice vetoed a bill to permit the government to buy surplus crops and sell them abroad because he feared overproduction and higher prices for consumers. Coolidge also pocket-vetoed a bill that would have let the government operate the Muscle Shoals power facilities as an electric power project.

“Keep Cool with Coolidge.”

Coolidge easily defeated all rivals for the Republican presidential nomination in 1924. The party’s national convention overwhelmingly nominated him on the first ballot and then selected Illinois Governor Frank Lowden as his running mate. After Lowden shocked the party by declining the nomination, delegates chose Charles G. Dawes, director of the Bureau of the Budget, for vice president. The Democrats nominated John W. Davis, former ambassador to the United Kingdom, for president, and Governor Charles W. Bryan of Nebraska for vice president. Dissatisfied members of both parties formed the Progressive Party. They nominated Senator Robert M. La Follette of Wisconsin for president and Senator Burton K. Wheeler of Montana for vice president.

Both Democrats and Progressives urged defeat of the Republicans because of the Harding scandals. Republicans replied with the slogan “Keep Cool with Coolidge.” Coolidge and Dawes received more than half of the popular votes cast in the election. On March 4, 1925, Chief Justice William Howard Taft became the first former president to administer the presidential oath of office. Coolidge’s inaugural address was the first to be broadcast by radio.

Foreign affairs

were marked by two main achievements: the improvement of relations with Mexico and the strengthening of ties with China. Coolidge appointed Dwight W. Morrow as ambassador to Mexico. Morrow settled some old disputes and also obtained valuable concessions from Mexico for American and British owners of oil property. Coolidge’s administration also reinforced the position of the United States as China’s main foreign friend.

Coolidge opposed joining the League of Nations but favored membership in the World Court. But the Senate placed what he called “unworthy” conditions on membership, and the president let the matter drop. Earlier, in 1923 and 1924, Dawes had directed an international committee that worked out a plan by which Germany could pay its World War I reparations (compensation for damages). See Dawes Plan.

Life in the White House

offered an interesting contrast between Coolidge and his wife. The difference was particularly noticeable at official receptions, where the president would be solemn and withdrawn and the first lady vivacious and charming.

The president had an interest in many behind-the-scenes details of running the White House. He inspected the kitchen and the iceboxes and commented on menus. He once protested because he thought six hams were too many for 60 dinner guests. Coolidge also liked to play practical jokes on the staff. He would sometimes push a button summoning guards and then hide behind draperies and watch them come running.

Tragedy struck the Coolidges shortly after his nomination in 1924. Their son Calvin developed a blister on a toe while playing tennis with his brother on the White House courts. The resulting infection spread, and the 16-year-old youth died of blood poisoning within a week. “When he went,” Coolidge later wrote in his autobiography, “the power and the glory of the presidency went with him.” This remark suggested that his interest in politics and in the presidency had waned. In 1926, the president’s father died, two weeks before his 81st birthday.

“I do not choose to run …”

The Coolidges traveled to the Black Hills of South Dakota for a summer vacation in 1927. On August 2, the day before the fourth anniversary of his presidency, Coolidge called newsmen to his summer office. He handed each reporter a slip of paper on which appeared the words: “I do not choose to run for President in 1928.”

Coolidge’s announcement caught the nation by surprise. Although he had told his father shortly after his son’s death in 1924 that he would never again be a candidate for political office, he had given no public clue as to his plans. He wrote in his autobiography that “The chances of having wise and faithful public service are increased by a change in the presidential office after a moderate length of time.” He also mentioned the “heavy strain” of the presidency, and expressed doubt that Mrs. Coolidge could serve four more years as first lady “without some danger of impairment of her strength.”

Coolidge had a typical response when reporters asked him to comment upon leaving the capital: “Good-by, I have had a very enjoyable time in Washington.” He was succeeded by Herbert Hoover on March 4, 1929.

Later years

The Coolidges returned to Northampton, but the stream of tourists past their home made it impossible to enjoy a quiet life. In 1930, Coolidge bought a Northampton estate called The Beeches, which had iron gates to keep curious visitors at a distance.

Coolidge completed his autobiography in 1929, first in magazine installments, then in book form. The next year, he began writing a series of daily newspaper articles called “Thinking Things Over with Calvin Coolidge.” He wrote chiefly about government, economics, and politics. He agreed to serve as president of the American Antiquarian Society, as honorary president of the Boy Scouts of America, and as a director of the New York Life Insurance Company.

The stock market crash in October 1929, and the resulting nationwide depression, distressed Coolidge, who felt that he might have done more to prevent it. But following the renomination of Herbert Hoover in 1932, Coolidge said that the Great Depression would have occurred regardless of which party had been in power.

Coolidge became increasingly unhappy as the Depression deepened and as voters elected Democrat Franklin D. Roosevelt to the presidency. On Jan. 5, 1933, Mrs. Coolidge found him lying on the floor of his bedroom, where he had died of a heart attack. He was buried beside his son and father in the Plymouth Notch cemetery.

Mrs. Coolidge sold The Beeches and built another home in Northampton, where she lived until her death on July 8, 1957. Coolidge had written: “For almost a quarter of a century she has borne with my infirmities, and I have rejoiced in her graces.”