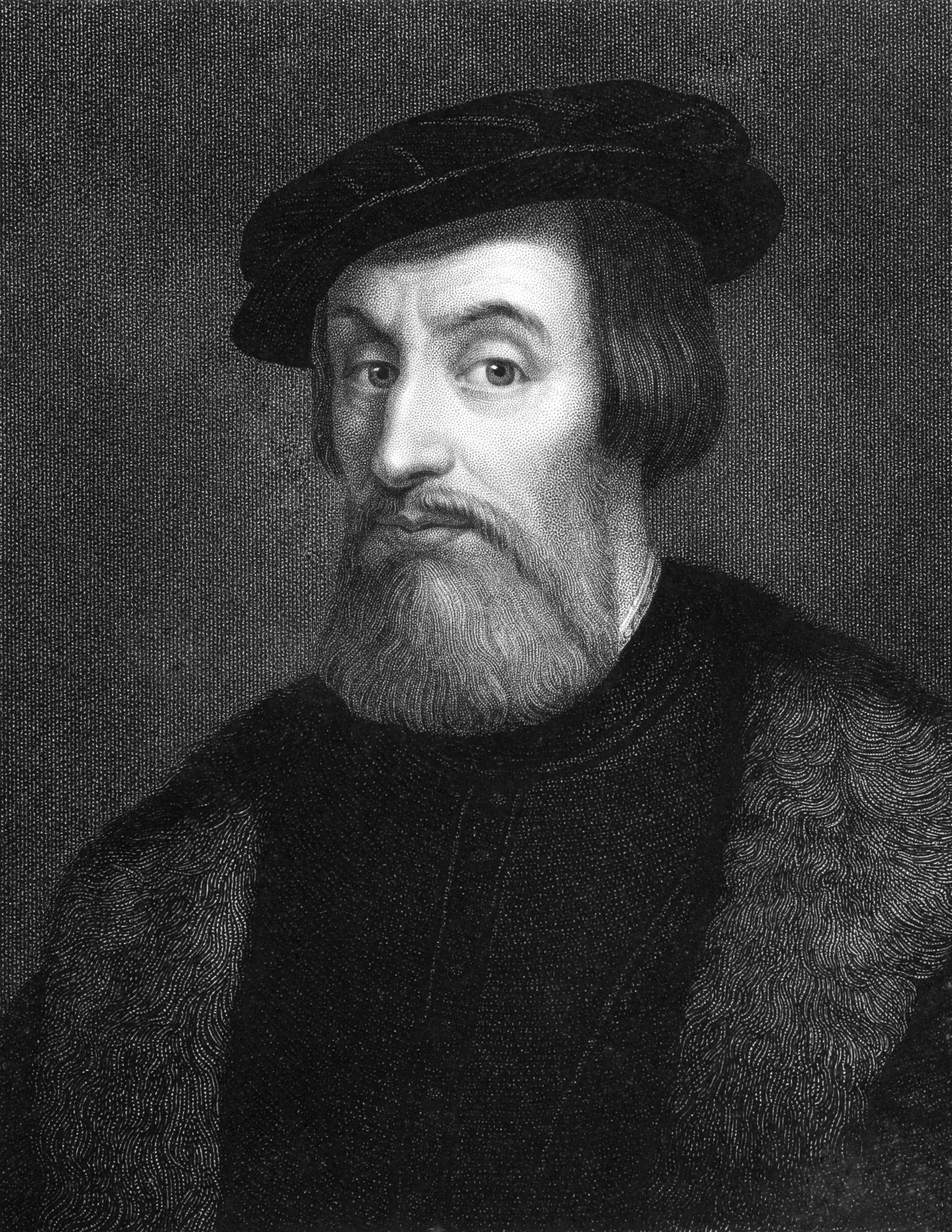

Cortés, Hernán, << kawr TEHZ or kawr TAYS, ehr NAHN >> (1485-1547), was a Spanish explorer who conquered what is now central and southern Mexico. His military triumphs were followed by 300 years of Spanish domination of Mexico and Central America.

Early life.

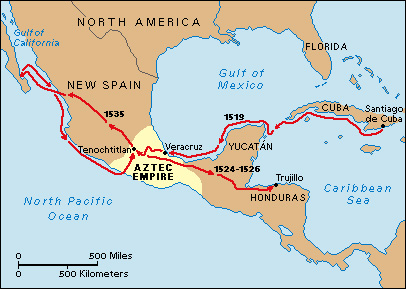

Cortés fought under Governor Diego Velázquez in a Cuban expedition that began in 1511. In 1518, Velázquez selected him to lead an expedition to the Yucatán Peninsula of Mexico, then a center of Maya civilization. Before Cortés could leave Cuba, Velázquez canceled the expedition, fearful of the voyage’s expense and distrustful of Cortés’s ambition. Cortés disobeyed and sailed for Yucatán in 1519, with about 500 men and 11 ships.

Arrival in Mexico.

Conquering Mexico took more than two years. At the start, Cortés skillfully made associations with Indian leaders, communicating through interpreters. One of these interpreters was a young Indian woman, Malintzin, also known as Malinche. The Indians of Tabasco had given her to the Spaniards as a peace offering. The Spaniards called her Marina. She became an adviser to Cortés, and she bore him a son.

From Yucatán, Cortés sailed northward along the coast of the Gulf of Mexico. He founded the first Spanish settlement in Mexico, La Villa Rica de Vera Cruz (modern-day Veracruz). Cortés appointed a town council, which gave him the title of captain general and the authority, under Spanish law, to conquer Mexico.

In August 1519, Cortés marched toward Tenochtitlan (now Mexico City), the capital of the Aztec Empire. Tenochtitlan had formed a union called the Triple Alliance with the neighboring cities of Texcoco and Tlacopan and had built an empire. The three cities forced other Indian villages to pay them taxes and to provide human sacrifices for their religious ceremonies. Many Indians resented the Aztec Empire for its cruelty and volunteered to help Cortés defeat it. Others joined Cortés after he defeated them in battle.

Victory over the Aztec.

At first, the Aztec emperor, Montezuma II , refused to meet with Cortés. But in November 1519, Montezuma allowed the Spaniards to enter Tenochtitlan. Cortés eventually took Montezuma hostage and tried to rule the empire through him.

Six months later, Cortés left the city to challenge a Spanish expedition led by Pánfilo de Narváez, who had been sent by Velázquez to arrest him. Cortés easily captured Narváez and persuaded Narváez’s troops to join him. Meanwhile, the people of Tenochtitlan rebelled. Soon after Cortés returned, Montezuma was wounded and died. The Spanish soldiers fled the city.

In December 1520, Cortés began to organize an attack against Tenochtitlan and its new leader, Cuauhtémoc. The city fell on Aug. 13, 1521. When brought before Cortés, Cuauhtémoc asked to die. Cortés, believing Cuauhtémoc knew where Aztec treasures were hidden, had him tortured, but Cuauhtémoc refused to tell any secrets. In 1525, Cortés had him hanged.

After the conquest.

King Charles I of Spain, who had become Holy Roman Emperor Charles V in 1519, appointed Cortés governor and captain general of the newly conquered territory. Cortés received the title Marqués del Valle de Oaxaca in 1528. He managed the founding of new cities and appointed men to extend Spanish rule to all of Mexico, which was renamed New Spain. Cortés also supported efforts to convert Indians to Christianity and sponsored new explorations. He led expeditions to Honduras in 1524 and to Baja California in northwestern Mexico in 1535 and 1536.

Cortés returned to Spain in 1540. His last battle was a Spanish attack on Algiers in 1541. He died on Dec. 2, 1547.