Cotton is the most widely used plant fiber. Cotton fibers are woven into soft, strong, absorbent fabrics to make clothing, bedsheets, carpeting, and other items. Other parts of the plant, especially the seed, provide raw materials for a wide variety of useful products.

People have cultivated the cotton plant and woven its fibers into cloth for thousands of years. Today, cotton is a part of almost every person’s life. Most people use cotton products daily.

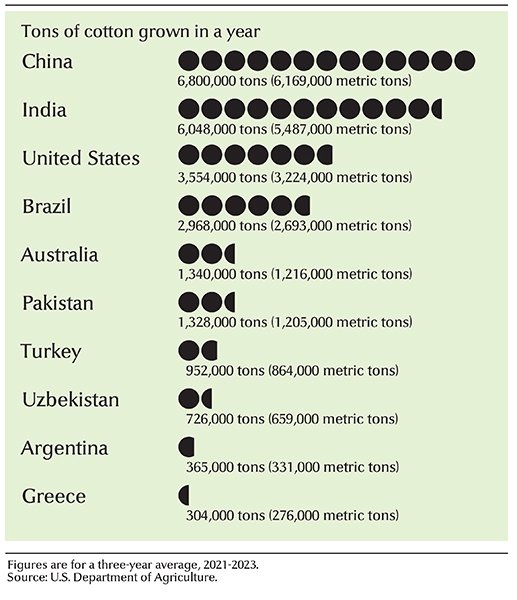

The leading cotton-growing countries are China, India, and the United States. Together, these three countries grow over half of the world’s cotton.

Uses of cotton

All parts of the cotton plant are useful. The most important part is the fiber, also called the lint. The lint grows from the seed coat (covering) of seeds inside the cotton boll (seed pod). Textile mills spin the fibers into yarn and weave the yarn into fabric. The linters (extremely short fibers on the seeds) are used in making padding, paper, explosives, and other products. Oil from cottonseeds forms the base of many food products. The food industry uses it as a cooking oil. Farmers often plow the stalks and leaves of cotton plants into the ground to return nutrients to the soil. Even the hulls of cottonseeds are useful. Hulls serve as livestock feed and as a soil conditioner to improve the texture of soil.

Cotton fibers

are used mostly to make clothing. Various types of cotton fibers can be woven into fabrics for different kinds of garments, from rugged work clothing to delicate dresses. Unlike most fibers, a cotton fiber can absorb moisture in its core. This absorbency makes cotton clothing feel cooler in summer and warmer in winter than other clothing does because it moves moisture away from the wearer’s skin. Clothing made of cotton also is durable because the fibers are strong.

Cottonseeds

are used in a wide variety of goods. Manufacturers use the linters from the seeds as raw materials for rayon, paper, and other products. Linters also are used to stuff mattresses and cushions. Bleached, sterilized linters are made into medical cotton pads.

Refined cottonseed oil is a popular cooking oil. It also is a main ingredient of such foods as salad dressing and margarine. Unrefined cottonseed oil is used to make soap, cosmetics, drugs, and other products.

The cottonseed meal that remains after oil extraction is a popular livestock feed and plant fertilizer. The dairy industry, in particular, uses the whole cottonseed to make feed for cattle. The hull or seed coat is used for animal feed and as a soil conditioner. Manufacturers also use the hulls to make plastics and synthetic rubber.

The cotton plant

Cotton is a woody shrub. In the wild, cotton is perennial—that is, it lives for more than two growing seasons. However, in most parts of the world, cotton is grown as an annual—that is, it lives and dies within one growing season. This section describes the upland cotton plant, from which most of the world’s cotton crop is produced.

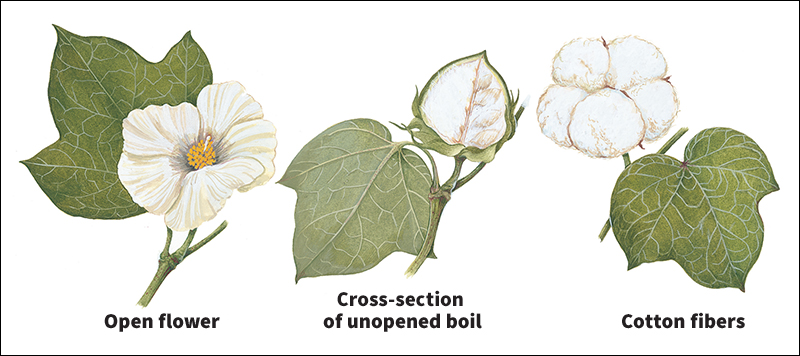

Appearance.

The mature upland cotton plant ranges from 2 to 5 feet (0.6 to 1.5 meters) in height. It has spreading branches. Depending on growing conditions, each branch may produce from one to several bolls. The plant’s leaves are 3 to 6 inches (7.5 to 15 centimeters) wide. Some of the leaves have three or five lobes. Others have no lobes. The plant’s taproot (long main root) may grow as deep as 4 feet (1.2 meters) into the ground.

Development.

Farmers in most countries plant cottonseeds in the spring. Seedlings emerge from the soil about a week after planting. Depending on growing conditions, squares (flower buds) begin to appear on the plants three to four weeks later. New squares continue to appear for about eight weeks. Each square grows for three to four weeks. It then opens into a creamy-white flower. The flower has five petals. The petals are surrounded by leaflike structures called bracts and specialized leaves known as sepals. The open flower measures about 2 inches (5 centimeters) across.

Pollination usually takes place within a few hours of the flower’s first bloom. The flower must be pollinated during the first day it is open. The second day after the flower blooms, its petals turn pink and then reddish-purple as they dry. The petals fall off by the third or fourth day. Usually, each flower pollinates itself.

After the petals fall, the seed pod develops into a boll. Inside the seed pod are about 20 to 40 seeds with fibers and linters growing from them. The seed pod matures into a green, walnut-sized boll in six to nine weeks. Then the boll begins to dry and split open. As the boll opens, drying causes the walls of the boll to curl back, exposing the fibers and seeds. At this time, the boll consists of three components: the seed, the lint, and the bur. The bur is the dried boll walls and the part of the boll that remains after the seed and lint are harvested.

Kinds of cotton

Scientists have identified dozens of species (kinds) of cotton plants. Only four species are cultivated. They are (1) upland; (2) Pima, also called Egyptian and American-Egyptian; (3) tree; and (4) Levant. Upland and Pima are the most widely grown commercial species. The different species resemble each other in most ways. But they differ in such characteristics as height, type of fibers, blooming time, and color of flowers. Each species has varieties with different qualities. For example, some varieties grow best on irrigated land, some have stronger fibers than others, and some take longer to mature.

The four main species fall into two groups: (1) New World cotton and (2) Old World cotton.

New World cotton

includes upland and Pima cotton. Native Americans in Central and South America first cultivated these types of cotton thousands of years ago. The plants are probably native to these regions.

Upland cotton

is cultivated in many parts of the world. The species may have gotten its name in the American Colonies. There, it was cultivated inland or, as the colonists said, “up land” from the Atlantic Coast.

Upland fibers measure from 3/4 to 1 1/4 inches (1.9 to 3.2 centimeters) long. They can be made into many kinds of fabrics, including heavy canvas and fine cloth.

Pima cotton

developed along the coasts of what are now Peru and Ecuador. American colonists cultivated the species as Sea Island cotton along the southeast Atlantic Coast of what is now the United States. Scholars believe that growers in the early 1800’s crossed Sea Island cotton with a variety of the same species in Egypt. Varieties developed from this cross were brought to the United States in the early 1900’s and became known as American-Egyptian cotton. Cotton marketed in the United States today as Pima is descended from the original Sea Island cotton and American-Egyptian cotton.

About 8 percent of the world’s cotton is Pima, Egyptian, and American-Egyptian. The fibers, which in most cases range from 1 1/4 to 1 1/2 inches (3.2 to 3.8 centimeters) long, are much stronger than upland cotton fibers. Pima cotton is used primarily to make high-quality clothing. It also is used to make sewing thread.

Old World cotton

includes tree cotton and Levant cotton. These species are native to northern Africa and parts of Asia. They are also called Asiatic species. Levant cotton was an important source of lint for centuries, until other species were introduced and became more profitable. Old World species are relatively unprofitable because they have short, coarse fibers and low crop yields. Today, most of the Old World cotton that is cultivated is used in the communities where it is grown.

Where cotton is grown

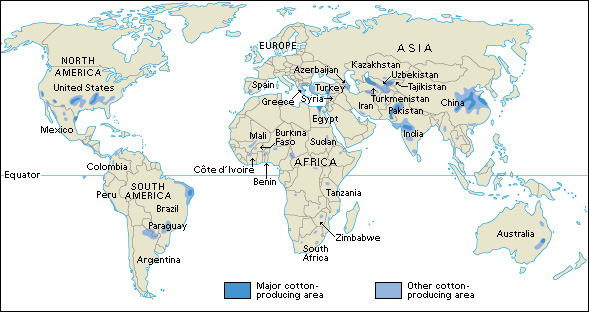

The cotton plant originated in the tropics, which have warm to hot temperatures the year around. Cotton is still considered a tropical plant species. Today, however, about half of the world’s cotton grows in temperate regions—that is, regions north of 30° latitude that have hot summers and cold winters. Farmers plant cotton mostly in areas that have 200 or more days a year in which temperatures do not drop below freezing.

Leading cotton-producing countries.

The world’s three largest producers of cotton are China, India, and the United States. China produces about 25 percent of the world’s cotton, and cotton textiles are a leading Chinese export. Cotton in China grows mainly in the east-central part of the country, near Beijing and Shanghai.

In India, cotton farming has greatly expanded. Most cotton is grown in the western half of the country.

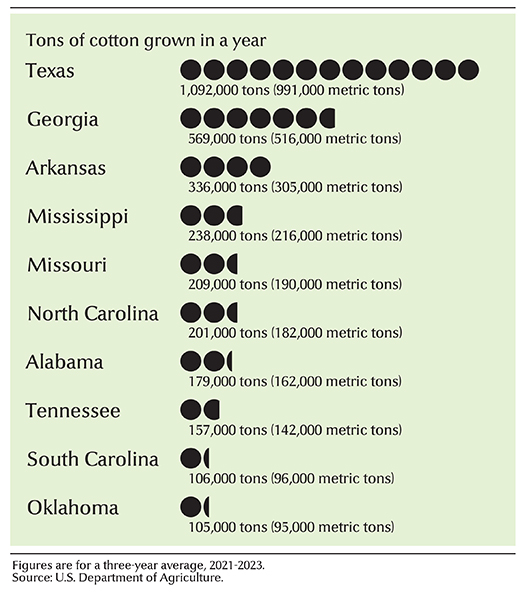

The United States grows about 15 percent of the world’s cotton, mostly in the South and Southwest. Texas produces by far the largest cotton harvest. Other leading cotton-producing states include Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Mississippi, and Missouri.

Other countries.

In addition to China and India, leading cotton-producing countries of Asia include Kazakhstan, Pakistan, Tajikistan, Turkey, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. Important South and Central American producers include Argentina, Brazil, and Peru. Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Côte d’Ivoire, Egypt, Mali, Nigeria, and Tanzania are the main cotton-producing countries in Africa. In Europe, cotton grows mainly in Greece and Spain. Australia also produces a large cotton crop.

How cotton is grown

Cotton requires a warm to hot climate and a growing season with many sunny days. The plant grows best in fertile, well-drained soil that gets adequate moisture during the growing season. Sunny, dry weather after the bolls open helps dry the fibers for harvest.

Soil must be rich in nitrogen, potassium, phosphorus, and certain other nutrients to produce a good cotton crop. In industrialized countries, most farmers apply these elements to the soil in the form of chemical fertilizer. Some farmers may combine the use of chemical fertilizers with that of manure. In less developed countries, nutrients may come mainly from manure.

Preparing the soil.

Farmers in the United States plant cottonseeds between February and June, depending on the region. Growers till (plow) the soil sometime between the last harvest and the new planting season. Tilling loosens the soil so that each seed can absorb moisture for sprouting. Tilling also plows under remains from the previous season’s crop. This material decays in the soil and fertilizes the new crop. In the United States and many other countries, farmers till the land mainly by machine. In less developed countries, people or animals pull the plows. Increasingly, farmers use reduced-tillage and no-tillage methods. These methods reduce fuel use and soil erosion.

Planting

is done by machines in most industrialized countries. It is usually done by hand in less developed countries. After tilling, most farmers prepare seedbeds (low ridges) in which they plant the cottonseeds. Planting in seedbeds rather than on a flat field warms the seeds. It also drains away excess moisture. Furrows (narrow grooves) between the beds carry water. In hot, dry areas, farmers may plant the seeds on a flat field or between extremely low beds. This practice helps the seeds to capture rainfall for sprouting and growth.

Care during growth

is important in producing a successful cotton crop. Cotton farmers must control diseases, insects, and weeds.

Diseases

of cotton fall into four categories: (1) seedling diseases, (2) wilt, (3) blight, and (4) rot. Seedling diseases attack roots and stems. They are caused by fungi. Cold, wet soils help bring on these diseases. To kill fungi, farmers may treat cottonseeds with chemicals before planting. They may also add chemicals to the soil along with the seeds at planting.

Wilts, blights, and rots are symptoms of plant diseases caused by specific bacteria and fungi. Wilt attacks the plant’s system for moving water through the stem. Blight attacks the leaves. Rot attacks the bolls. Farmers can best prevent these diseases by planting cotton varieties that are resistant to the disease-causing organisms and by using proper growing techniques. One such technique is crop rotation. In crop rotation, farmers alternate planting cotton with crops that do not support cotton diseases. This prevents disease-causing organisms from spreading from one year’s crop to the next. Another technique is a fertility program. Such a program involves testing the soil for proper nutrients and acidity. Malnourished plants are more susceptible to some diseases. However, excessive use of fertilizer makes plants more susceptible to other diseases.

Insect pests

destroy an estimated 15 percent of the world cotton crop each year. Various types of bollworms and boll weevils do most of the damage. These insects feed inside the bolls, damaging the fibers. Whiteflies leave a sticky film on the fibers. The film makes the fibers difficult to process. It can also cause an unsightly mold to grow on them. Farmers control insects mainly with chemical insecticides. They also use special growing methods and cultivate cotton varieties with some resistance to insects. In some areas, farmers destroy cotton stalks after harvest so insects cannot live on them. Some farmers try to keep areas near cotton fields free of vegetation that could provide food for harmful insects.

Weeds

reduce cotton yields by robbing the plants of moisture and nourishment. There are several ways to control weeds. Nearly all farmers grow cotton in rows, which makes weed removal easier. In many less developed countries, farmers remove weeds by hand. Most cotton farmers in the United States use herbicides (weedkillers) to control weeds. These chemicals prevent weeds from sprouting or kill them after they appear.

Harvesting

of cotton occurs about 150 to 200 days after planting. Farmers in many less developed countries harvest by hand. Farmers in industrialized countries use machine harvesters. Some countries use both methods. The following section describes machine harvesting.

Before harvest, many farmers apply a chemical called a defoliant to the crop. Defoliants cause the cotton plant to shed its leaves earlier than it would otherwise. Removing the leaves produces a number of benefits. It helps sunlight to dry the soil more quickly, which warms and dries the bolls. The bolls open more quickly under these conditions, allowing an earlier harvest. Removing the leaves also reduces the amount of trash (unwanted plant material) in the harvested cotton. Trash lowers the value of cotton because it makes ginning (separating the seed from the lint) more difficult. Trash may also cause flaws in yarn and cloth.

Growers use either a spindle picker or a stripper machine to harvest cotton. In the United States, most cotton is harvested by spindle picker. The spindle picker has a series of barbed spindles (rods). The spindles revolve as the machine moves along a row of cotton. The seed cotton (lint and seeds) catches in the spindles and is pulled from the bur. The machine then removes the seed cotton from the spindles and blows it into the picker.

Like spindle pickers, stripper machines pick seed cotton. But strippers also pull the burs and, in many cases, some leaves and stems off the plants. As a result, seed cotton harvested by a stripper machine generally contains more trash than that harvested by a spindle picker.

After harvest, many farmers use a large machine to press the seed cotton into modules (compressed stacks) that weigh about 20,000 pounds (9,000 kilograms). Farmers store the modules on or near the cotton field until they are transported for ginning. Other farmers load the seed cotton from the picker or stripper into large trailers. They take the cotton immediately to the gin.

Processing and marketing cotton

The processing and marketing of cotton varies somewhat from country to country. This section describes these activities in the United States.

Ginning and baling.

The term cotton gin applies to the entire mechanical system that performs a process called ginning. Ginning separates the fibers from the seeds, dries and cleans the fibers, and then presses the cotton into bales. The machines that separate the fibers from the seeds are also called gins.

Upland cotton is ginned on a saw gin. The saw gin grabs the fibers and breaks or cuts them away from the seeds. Pima cotton fibers are not as firmly attached to the seeds as upland fibers. They can be removed with a roller gin. A roller gin passes the seed cotton between two rollers that squeeze the seeds out from the fibers.

Special machines clean and dry the fibers after separation. The fibers are then compressed, wrapped, and tied into rectangular bales at the gin or at factories called compress warehouses. In the United States, most bales weigh about 500 pounds (230 kilograms) each.

Classing.

Before American farmers sell their cotton on the market, a government agency called a classing office evaluates fiber samples from each bale. Until 1991, inspectors known as classers graded the bales on the basis of three characteristics. They were: (1) the whiteness of the lint, (2) the amount of trash in the bale, and (3) how well the cotton was ginned. The classers also estimated the length of the longest fibers. They called this estimated length the cotton’s staple.

Today, classing offices also use devices called high volume instruments (HVI’s) to test and classify samples. HVI’s measure fiber length, strength, and diameter. They also determine the amount of trash in the sample and measure the whiteness.

Selling.

After classing, many U.S. farmers sell their cotton to a broker, also called a cotton buyer. Brokers, in turn, sell the cotton to shippers or textile mills. Some farmers sell directly to shippers or mills. Other producers pool their cotton to sell it to shippers or mills.

Sales to textile mills usually take the form of a forward contract. In such a transaction, a mill agrees to buy a specific amount of a certain quality of fiber at a given price at a specified future time. This transaction may occur before planting or during the growing season.

In the United States, cotton of average quality can also be bought and sold in the futures market on the New York Cotton Exchange, which is part of the New York Board of Trade. In the futures market, traders buy or sell contracts to receive or deliver a quantity of cotton at a specified future time. The price they pay is based on their estimate of what the future price will be. Buyers seldom actually receive the product for which they buy a contract. Instead, they sell the contract before delivery of the goods. If the price of cotton goes up after they buy the contract, they make a profit when they sell the contract. If the price goes down, they sell the contract at a loss. Cotton of higher-than-average or lower-than-average quality is traded in the United States in a spot market, where it is bought and sold for immediate delivery.

Making cotton into cloth

After cotton is harvested, ginned, and sold to textile manufacturers, spinning mills make it into yarn. The yarn is then made into cloth.

Cleaning and blending.

At the mill, workers remove the wrapping and ties from the bales. They place the bales in an arrangement called a lay-down. Layers are then peeled from the bales mechanically and blown to a spiker, or fluffer. This machine fluffs up the compressed cotton. Other machines then blend the fibers from different bales into a more even mixture. Once the cotton is blended, machines further clean and fluff the fibers and remove trash.

In most mills, the fibers then move through a series of air ducts to a carding machine. The carding machine straightens the fibers into a thin, filmy sheet. A machine forms the sheet into a loose rope called a card sliver << SLY vuhr >> . The sliver is coiled into drums.

Spinning

accomplishes three tasks. First, it reduces the card sliver from a thick rope to slender yarn. Second, it straightens the fibers. Third, it twists the fibers into yarn.

To begin, the card sliver is pulled into a series of rollers. In a process called drawing, the rollers make the sliver thinner and the fibers more parallel. Drawing turns the card sliver into a slimmer rope called a drawn sliver. Machines then pull the drawn sliver into a still thinner strand called a roving. The roving goes through more drawing. It is then twisted into yarn.

Lengths of yarn are tied end to end and wound on bobbins. In a process called warping, the yarn is wound onto a large spool called a beam. A slashing machine unwinds the yarn from the beam and dips it into a vat of sizing. Sizing is a mixture of starch, gum, and resins. These substances strengthen the fibers so they can better withstand weaving. After drying, the yarn is made into cloth by weaving, knitting, or other processes. Newly woven cotton fabric is grayish-white. It is called gray-state cloth, gray goods, or (pronounced greige << gray >> ).

Finishing

is the final step in the production of woven goods. This process removes impurities from the cloth. It also produces white fabrics that easily absorb dyes. Finishing consists of desizing, scouring, bleaching, and a process called mercerization.

Desizing soaks the fabric to remove the sizing. Machines then scour (wash) the fabric with a special solution to remove naturally occurring waxes. Bleaching makes the fabric uniformly white so it can be sold as white fabric or evenly dyed. Mercerization is the application of a chemical solution to the cloth. This process improves the luster of the fabric. It also makes it absorb dye more evenly.

After finishing, cotton that was not dyed before spinning or as yarn is dyed as fabric. Some cotton fabrics are preshrunk. Preshrinking prevents them from becoming too small after they have been sold as garments.

History

Cotton plant species developed in both the Eastern and Western hemispheres. The oldest remains of cotton in the New World are plant fragments. They date from 3000 B.C. or earlier and were found in present-day Mexico. In what is now Peru, Native Americans twined cotton to make fishing nets and other items as early as 2500 B.C. The earliest woven cotton also dates from about 2500 B.C. in that area. Native Americans in present-day Mexico and Peru used cotton extensively by about A.D. 1000.

The oldest evidence of cultivated Old World species comes from fragments of cotton fabric. The fragments date to about 3000 B.C. and come from the Indus River Valley region, in what are now Pakistan and western India. The region first exported cotton textiles to Mesopotamia about 1500 B.C. Mesopotamia was an area that included most of modern-day Iraq and parts of Syria and Turkey. Residents of Mesopotamia and nearby areas began cultivating their own cotton plants about 700 B.C. Europeans first grew and wove cotton in present-day Spain and Italy, in the A.D. 700’s. During the next several hundred years, cotton cultivation and weaving spread throughout much of Europe.

In England.

By the 1500’s, imported cotton textiles had become common in England. The English began to weave cotton in the 1600’s. At first, they imported raw cotton from countries bordering the Mediterranean Sea. Later, they imported it from America’s Southern Colonies. In a system of production called the cottage industry, people spun and wove cotton at home and sold the cloth to merchants.

The cottage industry system could not keep up with the demand for woven cotton textiles. The demand spurred the development of machines that could process cotton in large quantities. These machines were invented in England in the 1700’s. They were crucial in bringing about the Industrial Revolution, a period of rapid industrialization. They also made England one of the largest producers of woven cotton goods.

The first significant improvement in machinery for cotton processing was the fly shuttle, also called the flying shuttle. John Kay, an English inventor, developed it in 1733. The shuttle increased weaving speed by weaving the yarn mechanically rather than by hand.

The spinning jenny was invented about 1764 by an English weaver named James Hargreaves. It enabled spinners to provide more yarn more quickly to weavers. It was the first machine to spin more than one yarn at a time. Richard Arkwright, an English wigmaker, invented the water frame in 1769. It spun yarn even more quickly through the use of water power. Ten years later, a weaver named Samuel Crompton invented the spinning mule. This machine combined features of the spinning jenny and the water frame. It gradually replaced both.

American colonists

began growing cotton in the early 1600’s. They wove cotton into coarse cloth. In the United States, large-scale cotton growing began in the South in the late 1700’s. The colonists exported raw cotton to England, where it was made into woven fabric.

English manufacturers tried to keep the new spinning and weaving machines out of the United States. They wanted the United States to continue to sell its raw cotton to England and to buy back finished cloth. But Americans wanted to manufacture their own textiles. Finally, in the 1790’s, the first American cotton mills were built in New England. Other mills soon sprang up.

In 1793, Eli Whitney invented a cotton gin that separated cottonseeds from fibers quickly and economically. This gin could do the work of 50 people, making it possible to send more cotton to the mills. Cotton textile manufacturing in New England grew rapidly.

In the U.S. South,

the cotton industry expanded greatly with the invention of Whitney’s cotton gin. Cotton production increased from about 365,000 bales in 1815 to nearly 5 million bales in 1860. Cotton accounted for nearly 60 percent of the dollar value of U.S. exports in 1860.

At the time, cotton and other Southern crops were grown on plantations, which made use of slave labor. The slave population grew in the early 1800’s because planters needed more hands to pick and gin cotton. Many Southern plantation owners felt they could not grow cotton at a profit without slave labor. Many Northerners opposed slavery. This conflict became a major cause of the American Civil War (1861-1865).

In the 1830’s, some cotton mills began processing cottonseeds to extract cottonseed oil. But oil extraction was unsuccessful until just after the Civil War, when improved machines came into general use. Selling cottonseed oil then became profitable, and the number of mills processing cottonseeds grew. Also after the war, Southerners built mills to make cotton cloth. These mills prospered in part because land was cheaper and taxes lower than in the North. In addition, Southern laborers worked for lower wages than Northern workers did.

The boll weevil

began to seriously damage U.S. cotton crops in the 1890’s. This beetle, native to Mexico and Central America, had spread into Texas early in that decade. By the early 1900’s, it had multiplied across much of the South. Boll weevils cause the young squares to drop off the plant. This damage decreases the number of bolls that produce cotton fibers.

American cotton growers successfully fought off the boll weevil by modifying their growing methods. They picked and burned infested squares and bolls. They also planted cotton rows farther away from each other, reducing shade. Heat from the additional sunlight killed developing weevils. The cotton industry recovered in the 1920’s. But it faltered again in the 1930’s during the Great Depression, a severe worldwide economic slump.

The industrialization of agriculture

greatly changed cotton production in the United States in the 1900’s. Cotton production improved through the use of chemical fertilizers, herbicides, and insecticides. Slowly, farms began to use more machines. A modern six-row cotton picker can easily pick from 100 to 150 bales of cotton per day. The same work done by hand would require 500 to 750 laborers. The industrialization of cotton production eliminated the need for thousands of farm laborers, who sought work in other industries. Most of these workers were African American. Many thousands of workers and their families left the South to seek factory work in cities of the Midwest, North, and West. In African American history, this movement is sometimes called the Great Migration.

Synthetic fibers.

By 1960, the cotton industry was again thriving. Cotton accounted for about three-fourths of all fibers used in the United States. But this fraction began to shrink with the increasing popularity of synthetic fibers, such as acrylic and polyester. By 1977, only about one-third of all fibers used were cotton.

Decreased demand for cotton, as well as rising production costs, caused economic problems for cotton farmers. In response, the U.S. government took measures in the 1960’s and 1970’s to make it easier for farmers to obtain loans. It also gave money to farmers who met certain requirements. In 1971, cotton farmers formed an organization now called Cotton Incorporated. It supports cotton research, works to develop new cotton products, and promotes the sale of cotton products.

Government assistance helped many farmers stay in business during this period. Then, at the end of the 1970’s, demand for cotton clothing began to increase. Demand grew partly because people wanted softer, more comfortable clothing than could be made with synthetics. The increase also resulted from a drop in the price of cotton goods. In addition, manufacturers began to produce a wider variety of high-quality blends of cotton and synthetics. By 1990, cotton had rebounded to make up about half of the total fibers used. But in the early 2000’s, the U.S. cotton industry faced strong international competition in both cotton growing and the production of cotton textiles. The U.S. cotton industry suffered as a result.

Recent developments.

Farmers, researchers, and manufacturers are working to solve the problems that still face the cotton industry. Scientists have developed new varieties of cotton through genetic engineering. In genetic engineering, scientists directly alter an organism’s hereditary material to produce desirable traits. Cotton was among the first crops to be developed as a genetically modified organism (GMO). GMO cotton varieties may be more resistant to insect pests. These varieties also may enable farmers to use powerful herbicides, improving weed control. In addition, genetic engineering can improve the quality of the cotton fiber itself. Most cotton grown in the United States is now GMO cotton.

Some cotton farmers have begun to practice organic agriculture. Organic farms grow crops that are not genetically engineered. They also use little or no pesticides or chemical fertilizers. Supporters of organic agriculture hope to reduce the environmental pollution caused by industrialized agriculture.