Court is a government institution that settles legal disputes and administers justice. Courts resolve conflicts involving individuals, organizations, and governments. Courts also decide the legal guilt or innocence of individuals accused of crimes and sentence the guilty.

All courts are presided over by judges. These officials decide all questions of law, including what evidence is fair to use. In many cases, the judge also decides the truth or falsity of each side’s claims. In other cases, a jury decides any questions of fact. The word court may refer to a judge alone or to a judge and jury acting together. It also may refer to the place where legal disputes are settled.

Some court rulings affect only the people involved in a case. Other decisions deal with broad public issues, such as freedom of the press, racial discrimination, and the rights of individuals accused of a crime. In this way, courts serve as a powerful means of social and political change.

Types of courts

Courts differ in their jurisdiction (authority to decide a case). Generally, courts are classified as trial courts or appellate courts, and as criminal courts or civil courts.

Trial and appellate courts.

Nearly all legal cases begin in trial courts, also called courts of original jurisdiction. These courts may have general jurisdiction or limited, also called special, jurisdiction. Courts of general jurisdiction hear many types of cases. The major trial court of any county, state, or other political unit is a court of general jurisdiction. Courts of limited or special jurisdiction specialize in one or more types of cases, such as those involving juvenile offenders or traffic violations.

The losing side often has the right to appeal—that is, to ask that aspects of the case be reconsidered by a higher court called an appellate or appeals court. Appellate courts review cases decided by trial courts if the losing side questions the ruling of the lower court on a matter of law. Appellate courts cannot review a trial court’s decision on the facts.

Criminal and civil courts.

Criminal courts deal with actions considered harmful to society, such as murder and robbery. In criminal cases, the government takes legal action against an individual. The sentences handed down by criminal courts range from probation and fines to imprisonment and, in some states, death.

Civil courts settle disputes involving people’s private relations with one another. Civil suits involve such noncriminal matters as contracts, family relationships, and accidental injuries. In most civil cases, an individual or organization sues another individual or organization. Most civil decisions do not involve a prison sentence, though the party at fault may be ordered to pay damages.

How courts work

How criminal courts work.

Most individuals arrested on suspicion of a crime appear before a judge called a magistrate within 24 hours after the arrest. In cases involving minor offenses, the magistrate conducts a trial and sentences the guilty. In more serious cases, the magistrate decides whether to keep the defendant (accused person) in jail or to release him or her on bail. The magistrate also may appoint a state-paid defense attorney, called a public defender, to represent a defendant who cannot afford a lawyer.

Pretrial proceedings.

In a case involving a serious crime, the police give their evidence of the suspect’s guilt to a government attorney called a prosecutor. In some states, the prosecutor formally charges the defendant in a document called an information. The prosecutor presents the information and other evidence to a magistrate at a preliminary hearing. If the magistrate decides that there is probable cause (good reason for assuming) that the defendant committed the crime, the magistrate orders the defendant held for trial. In other states and in federal courts, the prosecutor presents the evidence to a grand jury, a group of citizens who decide whether the evidence justifies bringing the case to trial. If the grand jury finds sufficient evidence for a trial, it issues a formal accusation called an indictment against the suspect.

The defendant then appears in a court of general jurisdiction to answer the charges. This hearing is called an arraignment. If the defendant pleads guilty, the judge pronounces sentence. Many defendants plead guilty, rather than go to trial, in return for a reduced charge or a shorter sentence. This practice is called plea bargaining. Most criminal cases in the United States are settled in this way. But if the accused pleads not guilty, the case goes to trial.

Trial.

The defendant may request a jury trial or a bench trial, which is a trial before a judge. The jury or judge must decide if the evidence presented by the prosecutor proves the defendant guilty “beyond a reasonable doubt.” If not, the defendant must be acquitted (found not guilty).

If the defendant is found guilty, the judge pronounces sentence. Convicted defendants may take their case to an appellate court. However, prosecutors may not appeal an acquittal because the United States Constitution forbids the government to put a person in double jeopardy (try a person twice) for the same crime.

How civil courts work.

A civil lawsuit begins when an individual or organization, called the plaintiff, files a complaint against another individual or organization, called the defendant. The complaint formally states the injuries or losses the plaintiff believes were caused by the defendant’s actions. The complaint also asks for a certain amount of money in damages.

The defendant receives a summons, a notice that a complaint has been filed. It directs the defendant to appear in court on a certain date. The defendant then files a document called an answer. The answer contains the defendant’s version of the facts of the case and asks the court to dismiss the suit. The defendant also may file a counterclaim against the plaintiff.

In most cases, the complaint and the answer are the first of a series of documents called the pleadings. In the pleadings, the plaintiff and defendant state their own claims and challenge the claims of their opponents. Most civil cases are settled out of court on the basis of the pleadings. However, if serious questions of fact remain, a formal discovery takes place. This procedure forces each litigant (party involved in the case) to reveal the testimony or records that would be introduced as evidence in court. If the case still remains in dispute after the discovery, it goes to trial.

Civil cases may be decided by a judge or by a jury. The judge or jury determines who is at fault and how much must be paid in damages. Both sides may appeal.

Courts in the United States

The United States has a dual system of federal and state courts. Federal courts receive their authority from the U.S. Constitution and federal laws. State courts receive their powers from state constitutions and laws.

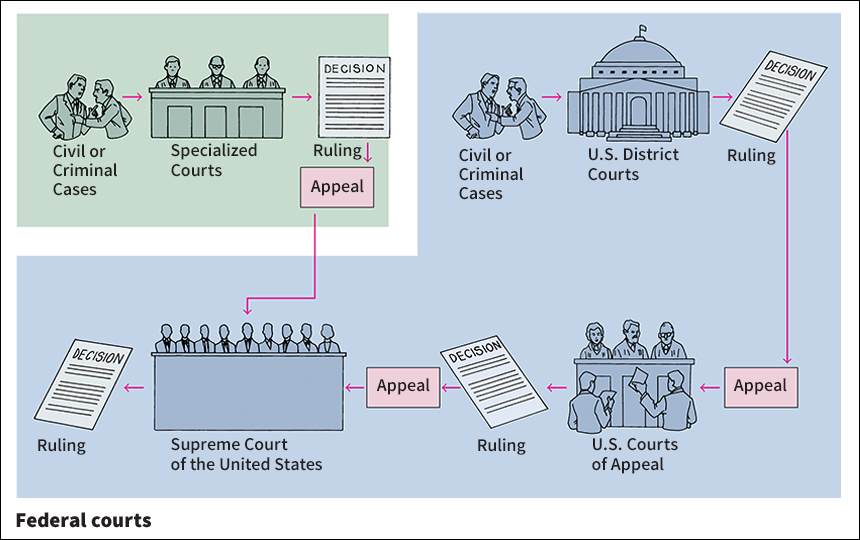

Federal courts

handle both criminal and civil cases involving the Constitution or federal laws, and cases in which the U.S. government is one of the sides. They also try cases between individuals or groups from different states, and cases involving other countries or their citizens. They handle maritime (sea) cases, bankruptcy actions, and cases of patent and copyright violation.

The federal court system includes district courts, courts of appeals, and the Supreme Court of the United States. District courts are federal courts of original jurisdiction—that is, they are the first courts to hear most cases involving a violation of federal law. The United States and its possessions have about 95 district courts. Each state has at least one such court.

Courts of appeals try federal cases on appeal from district courts. They also review the decisions made by such federal agencies as the Securities and Exchange Commission and the National Labor Relations Board. The United States is divided into 12 circuits (districts), each of which has a court of appeals. An additional federal court of appeals, the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, has nationwide jurisdiction.

The Supreme Court of the United States is the highest court in the nation. A person who loses a case either in a federal court of appeals or in the highest state court may appeal to the Supreme Court, but it may refuse to review many cases. In addition to its appellate jurisdiction, the court has original jurisdiction over cases involving two states or representatives of other countries.

The federal court system also includes several specialized courts. The United States Court of Federal Claims hears cases involving claims against the federal government. The Court of International Trade settles disputes over import duties. Taxpayers ordered to pay additional federal income taxes may appeal to the United States Tax Court. Military courts, called courts-martial, have jurisdiction over offenses committed by members of the armed forces. The United States Court of Appeals for the Armed Forces reviews court-martial rulings.

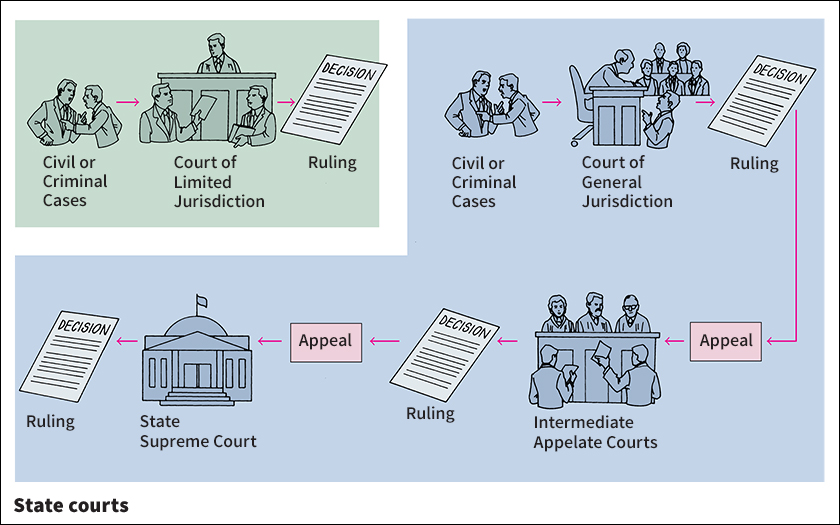

State courts.

The lowest state courts are courts of limited or special jurisdiction. Some of these courts handle a variety of minor criminal and civil cases. Such courts include police courts, magistrate’s courts, or county courts, and justices of the peace. Other lower courts specialize in only one type of case. For example, small-claims courts try cases that involve small amounts of money. Probate or surrogate courts handle wills and disputes over inheritances. Other specialized courts include courts of domestic relations, juvenile courts, and traffic courts.

Courts of general jurisdiction rank above courts of limited jurisdiction. These higher courts are known as circuit courts, superior courts, or courts of common pleas. About half the states have intermediate appeals courts, which hear appeals from courts of general jurisdiction. In some states, courts of general jurisdiction and appellate courts handle both criminal and civil cases. Other states have separate divisions on both levels. The highest court in most states is its supreme court.

Courts around the world

Courts in other countries.

The judicial systems of most countries are based on either common law or civil law. Some combine the features of both systems. This use of the term civil law refers to a legal system. It should not be confused with the branch of law dealing with people’s private relations with one another.

In common-law systems, judges base their decisions primarily on precedents, earlier court decisions in similar cases. Most English-speaking countries, including the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, and Australia, have common-law systems.

Civil-law systems rely more strictly on written statutes (legislative acts). Judges may refer to precedents, but they must base every ruling on a particular statute and not on precedent alone. Most European, Latin American, and Asian countries, and some African nations, have civil-law systems.

International courts

deal with disputes between nations. The International Court of Justice, a body of the United Nations (UN), meets at The Hague in the Netherlands. Its decisions are not binding unless the nations involved in the dispute agree to accept its rulings. In 1998, 120 UN member nations voted to approve a treaty calling for the establishment of an independent court, the International Criminal Court (ICC), for the prosecution of war crimes and other offenses. The court began operations in 2003.

History

Early courts.

Tribal councils or groups of elders served as the first courts. They settled disputes on the basis of local custom. Later civilizations developed written legal codes. The need to interpret these codes and to apply them to specific situations resulted in the development of formal courts. For example, the ancient Hebrews had a supreme council, called the Sanhedrin, which interpreted Hebrew law.

The ancient Romans developed the first complete legal code as well as an advanced court system. After the collapse of the West Roman Empire in the A.D. 400’s, the Roman judicial system gradually died out in western Europe. It was partly replaced by feudal courts, which were conducted by local lords. These courts had limited jurisdiction and decided cases on the basis of local customs.

Development of civil-law and common-law courts.

During the early 1100’s, universities in Italy began to train lawyers according to the principles of ancient Roman law. Roman law, which relied strictly on written codes, gradually replaced much of the authority of feudal courts in mainland Europe. In the early 1800’s, the French ruler Napoleon I used Roman law as the foundation of the Code Napoleon. This code, a type of civil law, became the basis of the court system in most European and Latin American countries.

By the 1200’s, England had established a nationwide system of courts. These courts developed a body of law that was called common law because it applied uniformly to people everywhere in the country. Common-law courts followed traditional legal principles and based their decisions chiefly on precedents. English common law became the basis of the court system for most countries colonized by England, including the United States and Canada.

Development of U.S. courts.

The American Colonies based their courts on the English common-law system. These colonial courts became state courts after the United States became an independent nation in 1776. Only Louisiana modeled its court system on civil law. In 1789, Congress passed the Judiciary Act, which created the federal court system.