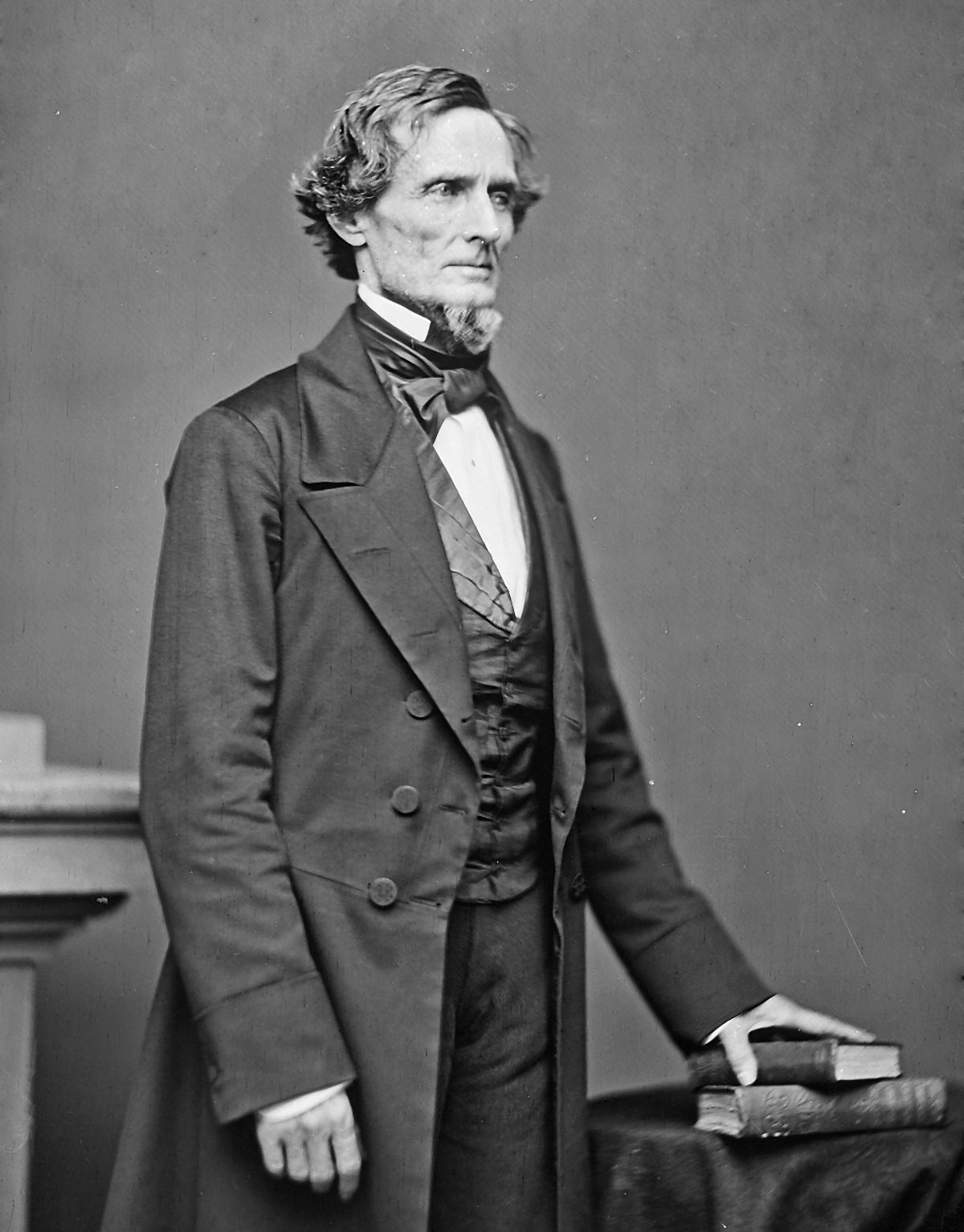

Davis, Jefferson (1808-1889), served as president of the Confederate States of America during the American Civil War (1861-1865). He was not always popular with the people of the South during the war. However, he won their respect and affection after the war through his suffering in prison and also through his lifelong defense of the Confederate cause.

Davis was a statesman with wide experience. He served in the United States House of Representatives and the Senate, and as a Cabinet member. He also won distinction as a soldier. He was a thoughtful student of the Constitution and of political philosophy.

Early life.

Davis was born on June 3, 1808, in Christian (later Todd) County, Kentucky. His father, Samuel Davis, was a veteran of the Revolutionary War. His older brother, Joseph, moved to Mississippi and became a successful planter. The Davis family moved there while Jefferson was still an infant, and he grew up in Wilkinson County. He attended the county academy, then entered Transylvania University in Kentucky. At the age of 16, he entered the U.S. Military Academy. He graduated with comparatively low grades in 1828. Davis’s Army career took him to Forts Howard and Crawford on the Wisconsin frontier. He participated in campaigns against the Indians and took charge of Indian prisoner removal after the Black Hawk War. Davis resigned from the Army in 1835.

Davis’s family.

In 1835, Davis married Sarah Taylor, daughter of his commander, Colonel Zachary Taylor, who later became a general and president of the United States. Davis took his bride to Mississippi and settled down to live as a cotton planter. But within three months, both he and his wife became ill with fever, and Mrs. Davis died. Davis traveled for a year, while he regained his strength. For several years after his return to his plantation, called Brierfield, Davis studied history, economics, political philosophy, and the Constitution of the United States. He managed his plantation successfully, and became wealthy.

In 1845, Davis married Varina Howell, whose family lived on The Briars, an estate near Natchez, Mississippi. The couple had six children: Samuel, Margaret Howell Hayes, Jefferson, Joseph, William, and Varina Anne. Varina Anne, nicknamed Winnie, became known as the Daughter of the Confederacy.

Mrs. Davis was a brilliant hostess. She did much to advance her husband’s political career and ably helped him during the Civil War.

His political career.

Davis became interested in running for office in 1843, and won a seat as a Democrat in the U.S. House of Representatives in 1845. He resigned from Congress in June 1846 to become a colonel in a regiment of Mississippi volunteers in the Mexican War. He served under General Zachary Taylor in northern Mexico, and distinguished himself for bravery in the battles of Monterrey and Buena Vista. His deployment of his men in a V shape gave him credit for winning the battle of Buena Vista (see Mexican War ). At a key moment in the Battle of Buena Vista, he deployed his men in a V shape to repel a Mexican attack. Despite a foot wound, Davis continued to lead his men throughout the battle.

The governor of Mississippi appointed Davis in 1847 to fill out the term of a United States senator who had died. The next year, the state legislature elected him for the rest of the term, and in 1850 for a full term. Henry Clay’s famous compromise measures came before the Senate in 1850, and Davis took an active part in opposing them in debate (see Compromise of 1850 ). He believed in a strongly proslavery interpretation of the Constitution, and loyally supported Senator John C. Calhoun, a Southern rights leader (see Calhoun, John C. ).

Davis believed that Mississippi should not accept the Compromise of 1850, and he resigned from the Senate to become the candidate of the States’ Rights Democrats for governor. He lost the election, and retired to his plantation in Wilkinson County.

Secretary of war.

President Franklin Pierce appointed Davis secretary of war in 1853. Davis improved and enlarged the Army during his term. He introduced an improved system of infantry tactics and brought in new and better weapons. He sent expeditions to explore routes for railroads from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Coast. He even tried the experiment of importing camels for Army use in the western deserts. At the close of the Pierce Administration in 1857, Davis was reelected to the Senate from Mississippi. In the Senate, Davis no longer advocated secession, but he defended the rights of the South and slavery. He opposed Stephen A. Douglas’ “Freeport Doctrine,” which held that the people of a territory could exclude slavery by refusing to protect it. Davis also opposed Douglas’ ambition to be the Democratic presidential candidate in 1860 (see Douglas, Stephen A. ).

Spokesman for the South.

Davis became the champion of the South’s claim that slavery must be legal in all the nation’s territories. He demanded that Congress protect slavery. In the positions he took, Davis considered himself the heir of Calhoun.

After Abraham Lincoln was elected president of the United States, Mississippi passed an Ordinance of Secession, and Davis resigned from the Senate. Davis hoped to become head of the Army of the Confederate States. But shortly after his return to Mississippi, the convention at Montgomery, Alabama, named him provisional president of the Confederacy. He took the oath of office on Feb. 18, 1861. He was inaugurated as regular president of the Confederacy on Feb. 22, 1862.

Confederate leader.

Davis had weaknesses. His health was poor, and he could be proud and irritable. He was sometimes reluctant to make risky but necessary decisions. Still, he was an able, hard-working administrator. Despite bitter opposition within the Confederate Congress, Davis almost always got the legislation he wanted. Most modern historians agree that he was the best available man for the job of Confederate president.

After the Confederacy’s major armies surrendered, Davis was captured and imprisoned at Fort Monroe, Virginia. A grand jury indicted him for treason, and he was held in prison for two years awaiting trial. Horace Greeley and other Northern men became his bondsmen in 1867, and he was released on bail. He was never tried.

His last years.

Davis spent his last years writing and studying at Beauvoir, his home at Biloxi, Mississippi, near the Gulf of Mexico. Davis published The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government in 1881 as a defense against his critics. Davis appeared often at Confederate reunions, and he eventually won the admiration of his fellow Southerners. He died on Dec. 6, 1889, and was buried in New Orleans. His body was moved to Richmond in 1893. The state of Mississippi presented a statue of Davis to Statuary Hall in the U.S. Capitol in 1931. Several Southern states celebrate an official holiday each year on or around Davis’s birthday, June 3.

See also Civil War, American ; Confederate States of America .