Declaration of Independence is the historic document in which the American Colonies declared their freedom from Britain (now the United Kingdom). The Second Continental Congress, a meeting of delegates from the colonies, adopted the Declaration on July 4, 1776. This date has been celebrated ever since as the birthday of the United States.

The Declaration of Independence eloquently expressed the colonies’ reasons for rejecting British rule. Its stirring opening paragraphs stated that the people of every country have the right to change or overthrow any government that violates their essential rights. The remainder listed ways the British government had violated American rights. The ideas expressed so majestically in the Declaration have long inspired the pursuit of freedom and self-government throughout the world.

Events leading to the Declaration.

During the 10-year period prior to the adoption of the Declaration, American leaders repeatedly challenged the British Parliament’s right to tax the colonies. Three efforts by Parliament to raise taxes provoked heated protest from the colonists. These efforts were the Stamp Act of 1765, the Townshend Acts of 1767, and the Tea Act of 1773.

The Stamp Act required colonists to pay for tax stamps placed on newspapers, playing cards, diplomas, and various legal documents. Colonial resistance forced Parliament to repeal the act in 1766. The Townshend Acts placed duties (taxes) on imported goods. The colonists reacted by boycotting British goods, which hurt British businesses. In 1770, Parliament removed the duties on all items except tea. The Tea Act made British tea cheaper than tea the colonists had been smuggling into the colonies. The British hoped the colonists would purchase the British tea at the lower price, and thereby acknowledge Britain’s right to tax them. But the residents of Boston defied the act by dumping hundreds of pounds of British tea into Boston Harbor. This event became known as the Boston Tea Party.

In 1774, Parliament responded to the Boston Tea Party by adopting laws that closed the port of Boston and gave the British-appointed governor of Massachusetts more power. In addition, the laws allowed British officials accused of crimes against Americans to be returned to Britain for trial. Angry colonists referred to these laws as the Intolerable Acts or the Coercive Acts.

The Continental Congress.

The Intolerable Acts alarmed the colonists. On Sept. 5, 1774, the First Continental Congress met in Philadelphia to plan common measures of resistance. All the colonies except Georgia sent representatives to the Congress. The delegates supported the view held by most colonists—that they could not be ruled by a Parliament in which they were not represented. The most Parliament could do, the delegates suggested, was pass laws regulating the trade of the British Empire. Most colonists still wanted to remain members of the empire, but they felt they owed allegiance only to the British Crown and not to Parliament. The delegates to the First Continental Congress hoped Britain’s King George III and his ministers would free the colonies from the Intolerable Acts.

In 1775, most colonists still did not favor declaring themselves independent of the British Crown. Such a declaration would cut the last bond linking the colonies to Britain. The delegates to the Second Continental Congress, which assembled on May 10, 1775, continued to hope the king would help resolve the colonists’ differences with Parliament. In July, the colonists sent a final petition to Britain declaring their loyalty to the king and asking him to address their complaints. But the king ignored their request and declared the colonies to be in rebellion.

Meanwhile, the American Revolution had begun in April 1775, when British troops clashed with colonial militia at Lexington, Massachusetts, and nearby Concord. In January 1776, the political writer Thomas Paine published Common Sense. This electrifying pamphlet attacked the concept of monarchy and made a powerful case for the independence of the American Colonies.

As the fighting intensified, hopes of reconciliation with Britain faded. On June 7, 1776, Richard Henry Lee of Virginia introduced a resolution to the Second Continental Congress stating that “these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States …” After several days of debate, the Congress appointed a committee to draft a declaration of independence. The committee gave the task to Thomas Jefferson of Virginia, who completed the work in about two weeks. Two other members, Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania and John Adams of Massachusetts, made a few minor changes.

Adoption of the Declaration.

On July 2, the Congress approved the Lee resolution. The delegates then began to debate Jefferson’s draft. A few passages, including one condemning King George for encouraging the slave trade, were removed. Most other changes dealt with style. On July 4, the Congress adopted the final draft of the Declaration of Independence.

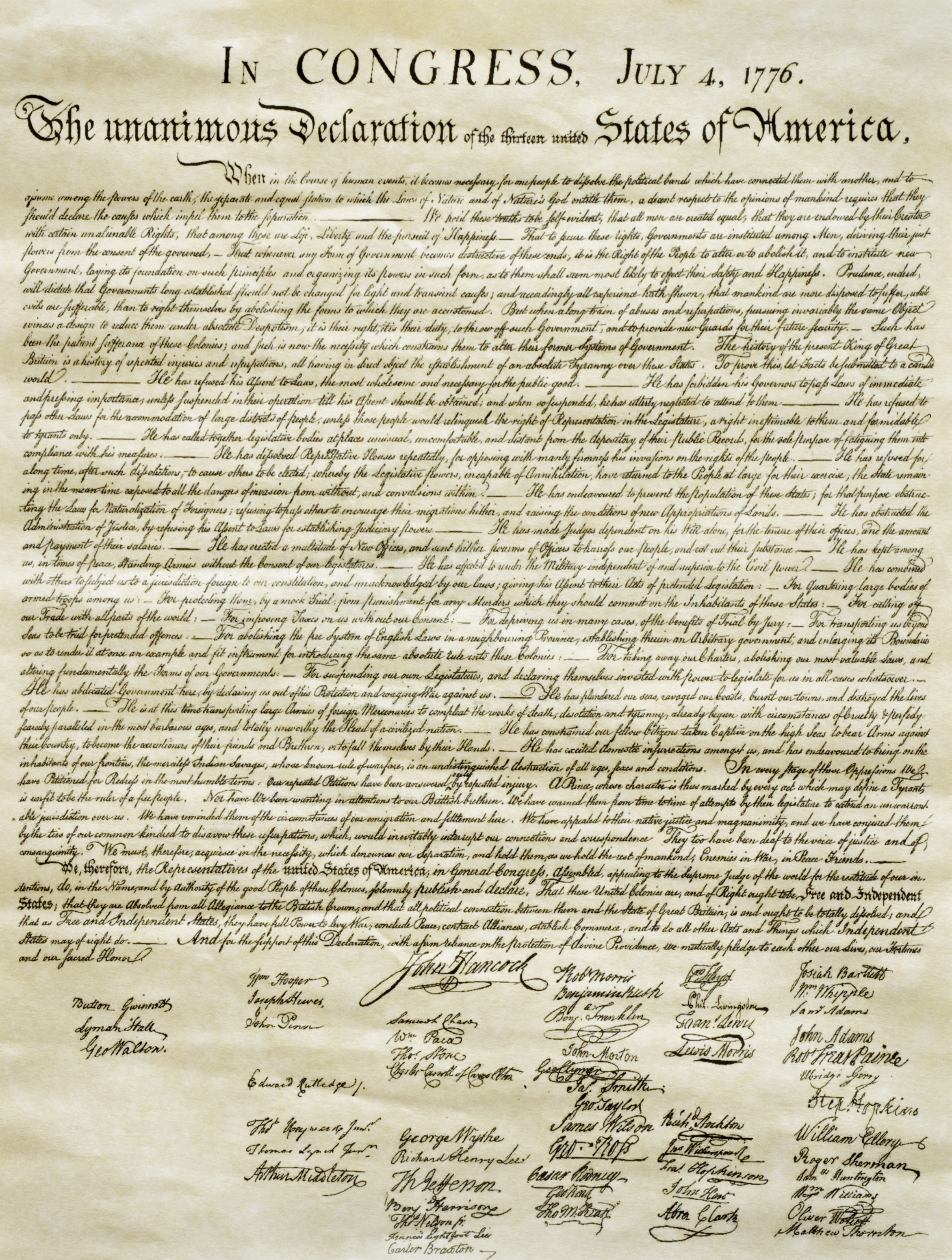

The Declaration was signed by John Hancock as president of the Second Continental Congress and by Charles Thomson, the Congress’s secretary. It was promptly printed and read to a large crowd in the State House yard on July 8. On July 19, the Congress ordered the Declaration to be engrossed (written in stylish script) on parchment. It also ordered that all its members sign the engrossed copy. Eventually, 56 members signed.

The importance of the Declaration

goes far beyond the reasons it provided for abolishing the colonies’ allegiance to King George III. Drawing upon the writings of the English philosopher John Locke and other English thinkers, it states two universal principles that have been important to developing democracies ever since. The first principle is that governments exist for the benefit of the people and not their rulers, and that when a government turns to tyranny (unjust use of power), the people of that country have a right to resist and overturn the government. The second principle, that “all men are created equal,” has served as a powerful reminder that all members of a society are entitled to the full protection of the law and to the right to participate in public affairs.

The original parchment copy of the Declaration is housed in the National Archives Building in Washington, D.C. It is displayed with two other historic American documents—the United States Constitution and the Bill of Rights.

The Declaration of Independence

The Declaration of Independence can be divided into four parts: (1) The Preamble; (2) A Declaration of Rights; (3) A Bill of Indictment; and (4) A Statement of Independence. The text of the Declaration is shown below. It follows the spelling and punctuation of the parchment copy. But unlike the parchment copy, each paragraph begins on a new line. The notes following each paragraph are not part of the Declaration. They explain the meaning of various passages or give examples of injustices that a passage mentions.

In Congress, July 4, 1776. The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen united States of America,

The Preamble

When in the Course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another, and to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation.—

Notes: This paragraph tells why the Continental Congress drew up the Declaration. The members felt that when a people must break their ties with the mother country and become independent, they should explain their reasons to the world.

A Declaration of Rights

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.—

Notes: In stating this principle of equality, the signers of the Declaration did not mean to deny all the inequalities of their own time. Americans had already rejected the idea of a legal aristocracy, but many still approved of or tolerated slavery. Most also assumed that the rights and duties of free men differed from those of free women. But over the years, this section has inspired the struggle against unequal treatment of the races and the sexes. The rights to “Life” included the right to defend oneself against physical attack and against unjust government. The right to “Liberty” included the right to criticize the government, to worship freely, and to form a government that protects liberty. The “pursuit of Happiness” meant the right to own property and to have it safeguarded. It also meant the right to strive for the good of all people, not only for one’s personal happiness.

That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed,—

Notes: The Declaration states that governments exist to protect the rights of the people. Governments receive their power to rule only through agreement of the people.

That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness. Prudence, indeed, will dictate that Governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes; and accordingly all experience hath shewn, that mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed. But when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object evinces a design to reduce them under absolute Despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their future security.—

Notes: People may alter their government if it fails in its purpose. Or they may set up a new government. People should not, however, make a revolutionary change in long-established governments for unimportant reasons. But they have the right to overthrow a government that has committed many abuses and seeks complete control over the people.

A Bill of Indictment

Such has been the patient sufferance of these Colonies; and such is now the necessity which constrains them to alter their former Systems of Government. The history of the present King of Great Britain is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations, all having in direct object the establishment of an absolute Tyranny over these States. To prove this, let Facts be submitted to a candid world.—

Notes: The Declaration states that the colonists could no longer endure the abuses of their government and so must change it. It accuses King George III of inflicting the abuses to gain total power over the colonies. It then lists the charges against him.

He has refused his Assent to Laws, the most wholesome and necessary for the public good.—

Notes: All laws passed by the colonial legislatures had to be sent to the British monarch for approval. George rejected many of the laws as harmful to Britain or its empire.

He has forbidden his Governors to pass Laws of immediate and pressing importance, unless suspended in their operation till his Assent should be obtained; and when so suspended, he has utterly neglected to attend to them.—

Notes: Royal governors could not approve any colonial law that did not have a clause suspending its operation until the king approved the law. Yet it took much time, sometimes years, for laws to be approved or rejected.

He has refused to pass other Laws for the accommodation of large districts of people, unless those people would relinquish the right of Representation in the Legislature, a right inestimable to them and formidable to tyrants only.—

Notes: The royal government failed to redraw the boundaries of legislative districts so that people in newly settled areas would be fairly represented in the legislatures.

He has called together legislative bodies at places unusual, uncomfortable, and distant from the depository of their public Records, for the sole purpose of fatiguing them into compliance with his measures.—

Notes: Royal governors sometimes had the members of colonial assemblies meet at inconvenient places.

He has dissolved Representative Houses repeatedly, for opposing with manly firmness his invasions on the rights of the people.—

Notes: Royal governors often dissolved colonial assemblies for disobeying their orders or for passing resolutions against the law.

He has refused for a long time, after such dissolutions, to cause others to be elected; whereby the Legislative powers, incapable of Annihilation, have returned to the People at large for their exercise; the State remaining in the mean time exposed to all the dangers of invasion from without, and convulsions within.—

Notes: After dissolving colonial legislatures, royal governors sometimes took a long time before allowing new assemblies to be elected.

He has endeavoured to prevent the population of these States; for that purpose obstructing the Laws for Naturalization of Foreigners; refusing to pass others to encourage their migrations hither, and raising the conditions of new Appropriations of Lands.—

Notes: The colonies wanted immigrants to settle in undeveloped lands in the West. For this reason, their laws made it easy for settlers to buy land and to become citizens. But in 1763, King George claimed the Western lands and began to reject most new naturalization (citizenship) laws. In 1773, he prohibited the naturalization of foreigners. In 1774, he sharply raised the purchase prices for the Western lands.

He has obstructed the Administration of Justice, by refusing his Assent to Laws for establishing Judiciary powers.—

Notes: The North Carolina legislature passed a law setting up a court system. But Britain objected to a clause in the law, which the legislature refused to remove. As a result, the colony had no courts for several years.

He has made Judges dependent on his Will alone, for the tenure of their offices, and the amount and payment of their salaries.—

Notes: The royal government insisted that judges should serve as long as the king was pleased with them and that they should be paid by him. The colonies felt that judges should serve only as long as they proved to be competent and honest. They also wanted to pay the judges’ salaries.

He has erected a multitude of New Offices, and sent hither swarms of Officers to harrass our people, and eat out their substance.—

Notes: In 1767, the British Parliament passed the Townshend Acts, which taxed various products imported into the colonies. Britain also set up new agencies to enforce the laws and appointed tax commissioners. The commissioners, in turn, hired a large number of agents to aid them in collecting the taxes.

He has kept among us, in times of peace, Standing Armies without the Consent of our legislatures.—

Notes: British armies arrived in North America to fight the French in the French and Indian War (1754-1763). The colonists resented the fact that British troops remained in the colonies after the war.

He has affected to render the Military independent of and superior to the Civil power.—

Notes: The British altered the civil government in Massachusetts and named as governor General Thomas Gage, commander of Britain’s military forces in America.

He has combined with others to subject us to a jurisdiction foreign to our constitution, and unacknowledged by our laws; giving his Assent to their Acts of pretended Legislation:—

Notes: The Declaratory Act, passed by Britain in 1766, claimed that the king and Parliament had full authority to make laws for the colonies. However, the Declaration of Independence maintained that the colonies’ own laws did not give the British that authority.

For quartering large bodies of armed troops among us:—

Notes: The royal government passed various quartering acts, which required the colonies to provide lodging and certain supplies to British troops stationed in America.

For protecting them, by a mock Trial, from punishment for any Murders which they should commit on the Inhabitants of these States:—

Notes: In 1774, Britain passed the Impartial Administration of Justice Act. Under this act, British soldiers and officials accused of murder while serving in Massachusetts could be tried in Britain.

For cutting off our Trade with all parts of the world:—

Notes: Britain passed many laws to control colonial trade. The Restraining Acts of 1775, for example, severely limited the foreign trade that several colonies could engage in. One act provided that American ships that violated the law could be seized.

For imposing Taxes on us without our Consent:—

Notes: This charge referred to all taxes levied on the colonies by the British, beginning with the Sugar Act of 1764.

For depriving us in many cases, of the benefits of Trial by Jury:—

Notes: British naval courts, which had no juries, dealt with smuggling and other violations of the trade laws.

For transporting us beyond Seas to be tried for pretended offences:—

Notes: This charge referred to a 1769 resolution by Parliament that colonists accused of treason could be sent to Britain for trial.

For abolishing the free System of English Laws in a neighbouring Province, establishing therein an Arbitrary government, and enlarging its Boundaries so as to render it at once an example and fit instrument for introducing the same absolute rule into these Colonies:—

Notes: In 1774, the Quebec Act provided for French civil law and an appointed governor and council in the province of Quebec. The act also extended Quebec’s borders south to the Ohio River.

For taking away our Charters, abolishing our most valuable laws, and altering fundamentally the Forms of our Governments:—

Notes: The Massachusetts Government Act of 1774 drastically changed the Massachusetts charter. It provided that councilors would no longer be elected but would be appointed by the king. The act also restricted the holding of town meetings and gave the governor control over all lower court judges.

For suspending our own Legislatures, and declaring themselves invested with power to legislate for us in all cases whatsoever.—

Notes: In 1767, Parliament passed an act suspending the New York Assembly for failing to fulfill all the requirements of the Quartering Act of 1765.

He has abdicated Government here, by declaring us out of his Protection and waging War against us.—

Notes: Early in 1775, Britain authorized General Gage to use force if necessary to make the colonists obey the laws of Parliament. The British fought the colonists at the battles of Lexington, Concord, and Bunker Hill. George declared the colonies to be in revolt and stated they would be crushed.

He has plundered our seas, ravaged our Coasts, burnt our towns, and destroyed the lives of our people.—

Notes: The British seized ships that violated the Restraining Act of December 1775. They also bombarded such seaport towns as Falmouth (now Portland), Maine; Bristol, Rhode Island; and Norfolk, Virginia.

He is at this time transporting large Armies of foreign Mercenaries to compleat the works of death, desolation and tyranny, already begun with circumstances of Cruelty & perfidy scarcely paralleled in the most barbarous ages, and totally unworthy the Head of a civilized nation.—

Notes: The British used German mercenaries (hired soldiers) to help fight the colonists.

He has constrained our fellow Citizens taken Captive on the high Seas to bear Arms against their Country, to become the executioners of their friends and Brethren, or to fall themselves by their Hands.—

Notes: The British forced American seamen on ships seized under the Restraining Act to join the British navy.

He has excited domestic insurrections amongst us, and has endeavoured to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages, whose known rule of warfare, is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes and conditions.

Notes: On Nov. 7, 1775, Virginia’s royal governor proclaimed freedom for all enslaved Black people who would join the British forces. British military plans included using Native Americans to fight colonists in frontier areas.

A Statement of Independence

In every stage of these Oppressions We have Petitioned for Redress in the most humble terms: Our repeated Petitions have been answered only by repeated injury. A Prince, whose character is thus marked by every act which may define a Tyrant, is unfit to be the ruler of a free people.

Notes: The Continental Congress had asked the king to correct many abuses stated in the Declaration. These appeals were ignored or followed by even worse abuses.

Nor have We been wanting in attentions to our Brittish brethren. We have warned them from time to time of attempts by their legislature to extend an unwarrantable jurisdiction over us. We have reminded them of the circumstances of our emigration and settlement here. We have appealed to their native justice and magnanimity, and we have conjured them by the ties of our common kindred to disavow these usurpations, which, would inevitably interrupt our connections and correspondence. They too have been deaf to the voice of justice and of consanguinity. We must, therefore, acquiesce in the necessity, which denounces our Separation, and hold them, as we hold the rest of mankind, Enemies in War, in Peace Friends.—

Notes: Congress had also appealed without success to the British people themselves.

We, therefore, the Representatives of the united States of America, in General Congress, Assembled, appealing to the Supreme Judge of the world for the rectitude of our intentions, do, in the Name, and by Authority of the good People of these Colonies, solemnly publish and declare, That these United Colonies are, and of Right ought to be Free and Independent States; that they are Absolved from all Allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain, is and ought to be totally dissolved; and that as Free and Independent States, they have full Power to levy War, conclude Peace, contract Alliances, establish Commerce, and to do all other Acts and Things which Independent States may of right do.—

And for the support of this Declaration, with a firm reliance on the protection of divine Providence, we mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes and our sacred Honor.

Notes: Because all appeals had failed, the signers of the Declaration, as representatives of the American people, felt only one course of action remained. They thus declared the colonies independent, with all ties to Britain ended.