Diefenbaker, << DEE fuhn `bay` kuhr, >> John George (1895-1979), served as prime minister of Canada from 1957 to 1963. One of the reasons for the defeat of Diefenbaker’s Progressive Conservative government was his refusal to accept nuclear warheads for defense missiles supplied by the United States. The Liberals won the election of April 1963, and Liberal leader Lester B. Pearson became prime minister.

The Progressive Conservative Party (called the Conservative Party before 1942) elected Diefenbaker as its leader in 1956. Diefenbaker led the party to victory in the 1957 election, and became the first Progressive Conservative prime minister in 22 years. In 1958, Canadians reelected the party with the largest parliamentary majority in the nation’s history. The Progressive Conservatives won again in the 1962 election, but did not have an absolute majority in Parliament. Diefenbaker’s government stayed in power only with the support of the small Social Credit Party.

As prime minister, Diefenbaker increased Canada’s social welfare programs and speeded development of the nation’s rich northland. Canada faced serious economic problems in the early 1960’s, and Diefenbaker adopted austerity measures to fight them. Under Diefenbaker, Canada increased its trade with Communist countries. The St. Lawrence Seaway was completed, and Georges-Philias Vanier became the first French-Canadian governor general of Canada.

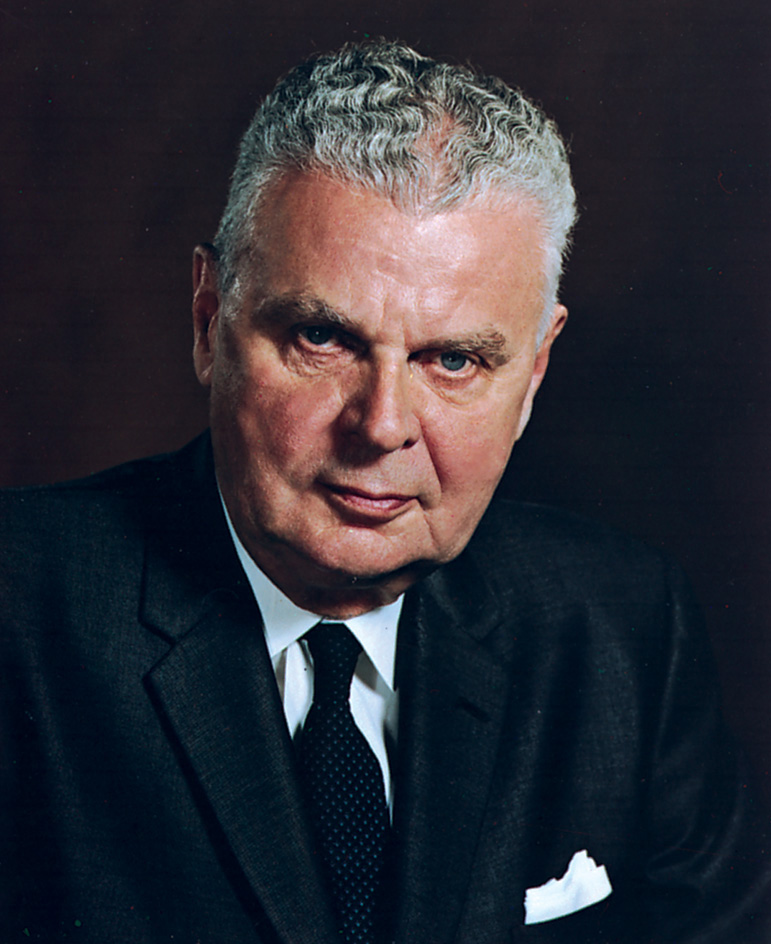

Tall and thin, with gray, curly hair and piercing blue eyes, Diefenbaker won friends and made enemies with his strong personality and fighting spirit. Diefenbaker made strong appeals to the national feeling of Canadians. “We are an independent country,” he declared, “and we have the right to assert our rights and not have them determined by another country.” Some people called Diefenbaker’s attitude “anti-American,” but he disagreed. “The very thought is repugnant to me,” Diefenbaker said. “I am strongly pro-Canadian.”

Early life

Boyhood and education.

John Diefenbaker was born on Sept. 18, 1895, in the village of Neustadt, Ontario. The family of his father, William, had come to Canada from Germany. His mother, Mary Florence Bannerman Diefenbaker, was a granddaughter of George Bannerman, a Scottish settler in the Red River Colony of Manitoba. John had a younger brother, Elmer.

John’s father taught school for 20 years, then became a civil servant. As prime minister, Diefenbaker recalled: “My father was a person who had a dedicated devotion to the public service. Throughout the schools he taught, there were a great many who went into public life, because of his feeling that it was one field in which there was a need.”

In 1903, the family moved to a homestead in Saskatchewan. John loved stories of the early days on the prairie. He was fascinated by tales about Gabriel Dumont, a leader of the Metis (persons of mixed white and American Indian ancestry) who revolted against the Canadian government in 1885. John also studied the lives of such men as United States President Abraham Lincoln, Prime Minister William Gladstone of the United Kingdom, and Emperor Napoleon I of France. See North West Rebellion .

John’s interest later shifted to Canadian history. One night, according to a family legend, he looked up from reading a biography of Prime Minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier and announced: “I’m going to be premier (prime minister) of Canada.” But John most admired former Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald.

In 1910, the Diefenbakers moved to Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, so John could attend high school there. John went on to the University of Saskatchewan, where he was active in campus politics. The college magazine predicted that someday he would lead the opposition in the House of Commons. He received his bachelor’s degree in 1915 and a master’s degree in 1916.

Diefenbaker was commissioned a lieutenant in the Canadian Army during World War I. He arrived in France in 1916, but returned to Canada the next year after being injured in training camp.

Young lawyer.

Diefenbaker had always planned to be a lawyer. “There was no member of my family who was a lawyer,” he said, “but I never deviated from that course from the time I was 8 or 9 years of age.” He studied law at the University of Saskatchewan and received his law degree in 1919. That same year, he opened a small office in the nearby town of Wakaw.

Diefenbaker developed an outstanding reputation as a defense lawyer. Some people who heard him in court claimed he could hold a jury spellbound with his oratory. “I just chat with the jury,” said Diefenbaker.

In 1923, Diefenbaker moved to the city of Prince Albert, Saskatchewan. He became a King’s Counsel—that is, a lawyer who serves the king or queen—in 1929, and was a vice president of the Canadian Bar Association from 1939 to 1942.

Diefenbaker married Edna May Brower in 1929. She died in 1951. Two years later, he married Olive Freeman Palmer, an old friend from Wakaw. Palmer, a widow with a grown daughter, was assistant director of the Ontario Department of Education.

Member of Parliament

In 1925 and 1926, Diefenbaker ran as a Conservative candidate for the Canadian House of Commons and lost. He ran for the Saskatchewan legislature in 1929 and 1938 and was defeated each time. Diefenbaker also lost an election for mayor of Prince Albert in 1934.

However, Diefenbaker’s defeats did not discourage him. In 1936, he was elected leader of the Saskatchewan Conservative Party. In 1940, 1945, and 1949, Diefenbaker was elected to the federal House of Commons to represent the riding (district) of Lake Centre. And in 1953, he became a representative for Prince Albert riding.

As a lawyer, Diefenbaker had made a reputation by defending individual civil rights. As a member of Parliament, he argued for a national bill of rights. Canada’s first bill of rights was adopted in 1960 when Diefenbaker was prime minister.

The first bill Diefenbaker introduced in Parliament provided for Canadian citizenship for Canadians. They were then British subjects. Diefenbaker denounced what he called “hyphenated citizenship.” He meant that every Canadian was listed in the census by the national origin of his father, such as French or Italian.

In 1948, the Progressive Conservatives met to choose a leader to succeed John Bracken. Some members suggested Diefenbaker, but the party chose George Drew. In 1956, Drew became ill and gave up politics. The party then chose Diefenbaker as leader in December 1956.

The Progressive Conservatives, discouraged after a long period of Liberal rule, held little hope for a victory in the 1957 election. But Diefenbaker waged a vigorous campaign. He charged that the Liberals had grown too powerful. Diefenbaker seemed to radiate vitality as he told of his plans for developing northern Canada.

In the 1957 election, the Progressive Conservatives won more seats in Parliament than any other party, though they did not win a majority. Diefenbaker became the first Conservative prime minister since Richard B. Bennett, who served from 1930 to 1935.

Prime minister (1957-1963)

John G. Diefenbaker, the first prime minister of Canada without English or French ancestry, took office on June 21, 1957. He succeeded Louis S. St. Laurent.

Parliament passed several bills sponsored by Diefenbaker’s government. One bill increased old-age pensions. Other legislation provided loans to economically depressed areas. Another bill gave financial aid to expand hydroelectric power in the Atlantic provinces.

In 1958, Diefenbaker asked for a new election. He wanted more supporters in Parliament to help him pass his legislative program. His party won 208 of the 265 seats in the House of Commons–the largest parliamentary majority in Canadian history.

Much of Diefenbaker’s social legislation soon became law. Parliament increased pensions for the blind and disabled and approved a program of federal hospital insurance. In 1958, the government began to build roads into Canada’s rich but undeveloped northland.

Economic problems.

After 1957, Canada’s economy grew slowly. Unemployment rose to more than 7 percent in 1961, and many Canadians blamed Diefenbaker. Diefenbaker worried about Canada’s trade deficit with the United States—that is, Canada imported more goods from the United States than it exported to that country. He wondered if he could redirect some Canadian trade to the United Kingdom, but there was no way to do so.

By the middle of 1962, Diefenbaker was forced to adopt austerity measures to boost the economy. The government lowered the value of the Canadian dollar. It reduced spending, raised tariffs on imports, and borrowed about $1 billion from foreign banks. In the election of June 1962, the Progressive Conservatives won the most seats in Parliament, but not an absolute majority. Diefenbaker remained prime minister only because the Social Credit Party supported him.

Nuclear controversy.

As prime minister, Diefenbaker had difficulty making decisions. His failure to reach an agreement with the United States on a matter of defense ultimately ended his administration. In 1961, Diefenbaker’s government announced that the United States would supply Canada with antiaircraft missiles for the defense of North America. But after receiving the missiles, Diefenbaker refused to arm them with atomic warheads. This annoyed the U.S. government, because Diefenbaker had asked for the missiles in the first place.

On Jan. 30, 1963, the United States charged that Canada had failed to propose a practical plan for arming its forces against a possible Soviet attack. Diefenbaker angrily answered that the U.S. statement was “an unwarranted intrusion in Canadian affairs.” He opposed acquiring nuclear warheads, saying that United States control of the missiles would threaten Canadian sovereignty. However, Liberal leader Lester B. Pearson declared Canada should live up to its agreement with the United States and accept nuclear warheads. On Feb. 5, the House of Commons passed a motion of no-confidence in Diefenbaker’s government, and the government fell from power.

In the election of April 1963, the Liberals won 129 seats in the House of Commons. This was just short of an absolute majority of the 265 seats, but more than any other party won. The Progressive Conservatives won only 95 seats. Pearson succeeded Diefenbaker as prime minister on April 22, 1963.

Later years

Diefenbaker led the opposition in Parliament until 1967, when the Progressive Conservatives chose Robert L. Stanfield to succeed him. Diefenbaker continued to represent Prince Albert in the Canadian House of Commons. He served as chancellor of the University of Saskatchewan from 1969 until his death.

Diefenbaker died of a heart attack at his home in the Ottawa suburb of Rockcliffe Park on Aug. 16, 1979. He was buried in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan.

See also Canada, History of ; Pearson, Lester B. ; Prime minister of Canada .